Improving the quality of care for service personnel with PTSD and depression

Healthy and fit troops depend on the physical and mental readiness of each service member. Untreated post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression can have a significant impact on troop readiness.

The Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury, part of the U.S. Department of Defense’s Office of Defense Health and Human Services, commissioned the RAND Corporation to conduct a multi-year study of the treatment of service members suffering from these disorders and to recommend strategies to continuously improve the quality of psychological care provided to service members in the military health care system.

This study is one of the most comprehensive ever conducted on mental health care in the military and provides the most complete picture to date of the characteristics of soldiers diagnosed with PTSD or depression, the quality of care they receive, and disparities in care within the MHS.

The MHS has done an excellent job of ensuring that service members with PTSD or depression are appropriately screened for suicide risk and comorbid psychiatric conditions

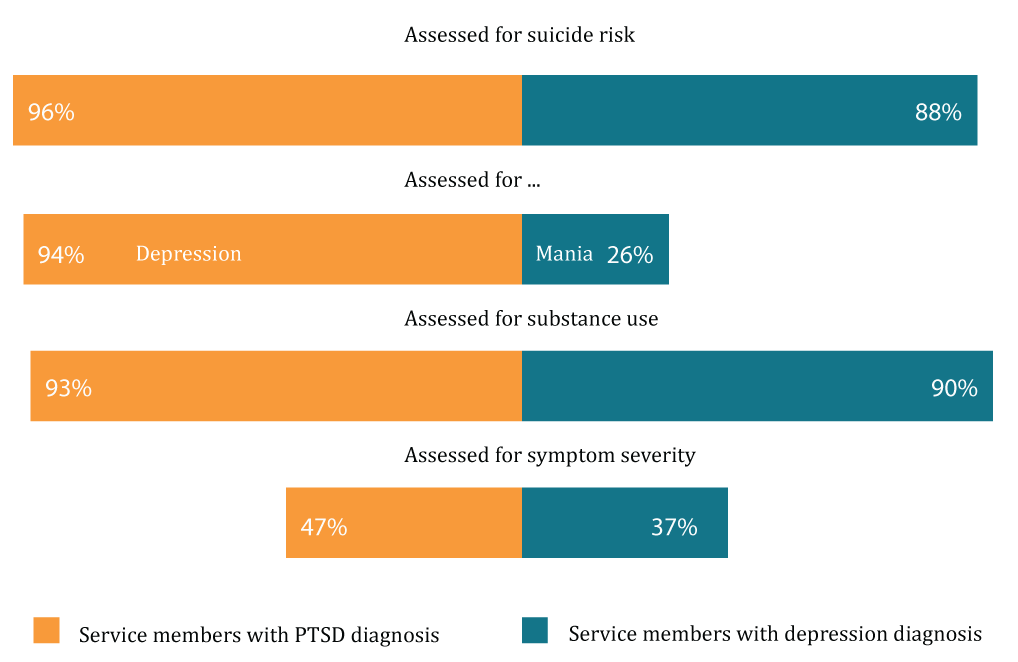

The RAND study found that most service members with PTSD or depression were appropriately screened at the onset of a new episode of care. More than 90% of service members with PTSD were assessed for suicide risk and comorbid depression or substance abuse. The adequacy of assessments for service members with depression was also high. Nearly 90% were considered at risk for suicide and 90% had a recent history of substance abuse.

However, only one-quarter of depressed service members were screened for manic-depressive symptoms, suggesting that there is still room for improvement. The study found that less than half of service members with PTSD or depression were assessed for symptom severity using a standardized measure, a key strategy for monitoring whether service members are improving.

Assessing quality of care

Clinical practice guidelines describe how patients with a given condition are treated. Guidelines are based on the best available evidence, such as clinical trials, and expert opinion. Guidelines for the treatment of PTSD and depression define how patients should be assessed at the start of treatment and how they should be treated at different stages of treatment, including the recommendation of certain types of psychotherapy and medication.

Quality indicators are used to determine the proportion of patients who receive the recommended treatment. They are an important tool for understanding the quality of patient treatment by providers and can indicate aspects of treatment that need to be improved.

The study assessed the quality of care provided by EMS between 2012 and 2014 using 30 quality indicators designed to meet clinical practice guidelines, using data from administrative records, medical records, and symptom questionnaires.

Most service members with PTSD or depression received the recommended assessments, but fewer received an assessment of symptom severity

SHSM can enhance the recommended treatment for PTSD and depression

“To me, it is very important that we take care of our wounded soldiers. And emotional injuries are very real. We are learning more and more about how to treat these types of illnesses, we are learning more and we need to do more because we are learning more. We owe it to these people.” (Ashton Carter)

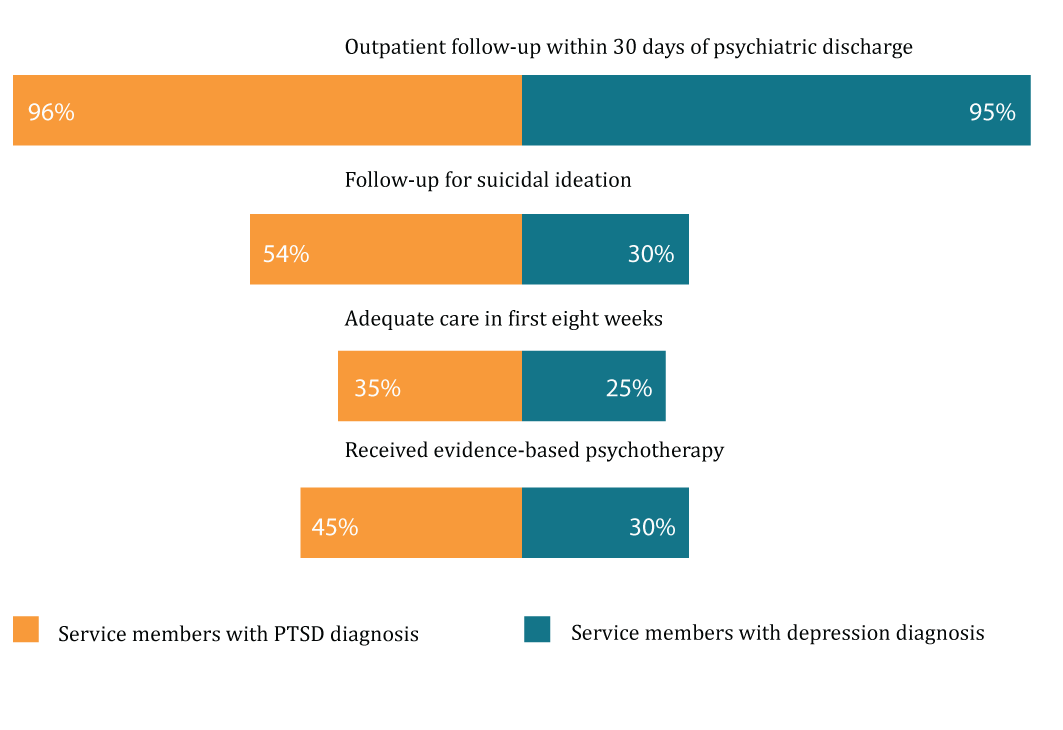

The MHS continues to be a leader in providing timely outpatient follow-up to service members discharged from psychiatric hospitals. More than 95% of service members with PTSD or major depressive disorder had a follow-up outpatient visit within 30 days of discharge. However, the study also identified several key areas for improvement.

While the MHS ensured that most soldiers initiating a new episode of treatment for PTSD or depression were assessed for suicide risk, fewer soldiers received adequate follow-up care when suicide risk was identified (54% of patients with PTSD and 30% of patients with depression).

In addition, fewer patients with newly diagnosed PTSD or depression received adequate initial treatment within eight weeks of diagnosis, i.e., at least four psychotherapy sessions or two treatments (36% for PTSD and 25% for depression).

Of the PTSD patients who received psychotherapy, 45% received evidence-based psychotherapy. Of the patients with depression who received psychotherapy, 30% received cognitive-behavioral therapy, an evidence-based method that has been shown to be effective in treating patients with depression.

The results show that, in general, the treatment of PTSD is generally better than that of depression in HSM. However, in 2012-2013 and 2013-2014 SHM improved slightly in most aspects of treatment measured.

Although the study did not find a significant association between receipt of recommended treatment and improvement in patients’ symptoms at six months for both PTSD and depression, further research is needed to determine the best approaches to improve patient outcomes. The largest differences in quality measure scores were observed by service, region, grade, and age.

For example, for PTSD and depression, follow-up within seven days of mental health hospital admission varied by about 15% across services. By region, there was a 12% variation in the number of follow-up visits in the 30 days following the initiation of new treatment for PTSD. Significant differences were also found by race/ethnicity and salary level in whether patients received adequate pharmacological treatment for PTSD or depression.

Not all service members with PTSD or depression received the recommended initial and ongoing treatment

The RAND Approach

Data were drawn from three sources: the medical records of 38,828 active-duty military members diagnosed with PTSD or depression in 2013; a random sample of the medical records of soldiers who received treatment for these conditions at military treatment centers; and symptom questionnaires completed by soldiers.

RAND tracked the care of service members diagnosed with PTSD or depression for 1 year, assessing the quality of care received and whether there were differences in quality of care by branch of service, geographic area, or service member characteristics.

Recommendations

- Focus first on the areas most in need of improvement. Although the study analyzed 30 areas of care to identify key strengths and areas for improvement, quality improvement is most effective when improvements are targeted to specific priority areas of care.

- Initiate efforts to regularly assess and report on quality. To this end, an institution-wide mental health care quality monitoring system could be established. Systematic reporting on quality-both by health care providers and other service providers who treat the people they serve-would increase transparency and encourage quality improvement.

- Monitor treatment outcomes for service users with mental health problems. Monitoring treatment outcomes is an essential element of measurement-based care. Priorities should include implementing patient outcome tracking strategies across facilities and among providers, and ensuring that providers are trained to integrate outcome data into their clinical practices.

- Investigate the causes of variation in quality of care. It is essential that health care services be equitable within the U.S. military. However, the study found that there are differences in quality of care across military branches, regions, and military characteristics. Investigating the causes of these differences would help eliminate them.

Read our general and most popular articles

- Diaetoxil

- Nuubu

- Regener 8

- CBD Vital

- Nordic Oil

- Potencialex

- Diaetostat

- Figur Kapseln

- Viscerex

- Prostaphytol

- Nutra Prosta

- Nutra Flex

- Diaetolin

- Matcha Slim

- Hepafar Forte

- Derila Kissen

- Exodermin

- HHC

- HHC Vape

- KU2 Cosmetics Hyaluronsäure Serum

- Liba Capsules

- KetoXplode

- Green Gummies

- Liver Ignite

- Ketoxboom Fruchtgummis

- Viagra Alternative

- Gundry MD Energy Renew

- ProDentim

- Phentermine Over The Counter

David W. Newton is a board certified pharmacist and also has been a board member for boards of examiners for the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy since 1983. His areas of expertise are primarily pharmaceuticals as well as cannabinoids. You can read an article about his expertise in CBD on the National Library of Medicine.

Reviewed by: Kim Chin and Marian Newton