I was searching the internet and noted with interest a reference to my uncle Anthony J. Korkuc on your website. I appreciate that you have included my uncle’s listed in your website but would prefer that you include the following text instead.

Anthony “Korky” Korkuc, from Seekonk, Massachusetts, 26 years old, was killed in action during a raid on Augsburg, Germany on February 25, 1944 during the Big Week. He served as the crew’s Ball Turret Gunner. The B-17 (A/C # 42-37786) from the 381st Bomb Group, was shot down after leaving the safety of the formation. Three ME-109’s attacked the B-17.

Korkuc and five other crewmates were killed on the mission. After being temporarily interred in Willmandingen, Germany, and St-Avold, France, the four men were returned to the United States for final burial on June 29, 1950. They are buried in Section 34, Gravesite 1631 in a group burial at Arlington National Cemetery. They are buried in the same section as General of the Air Force Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, who commanded all Army Air Forces in World War II.

The other crewmates sharing eternity with him are Navigator Earl Wonning (Indiana), Radio Operator Boyd Burgess, and Tail Gunner Dale E. Schilling.

Thanks, Bob Korkuc.

18 May 2008:

By: Rebecca Rule

Rebecca Rule, a writer who lives in Northwood, writes this column weekly except the last Sunday of the month.

Nashua Telegraph

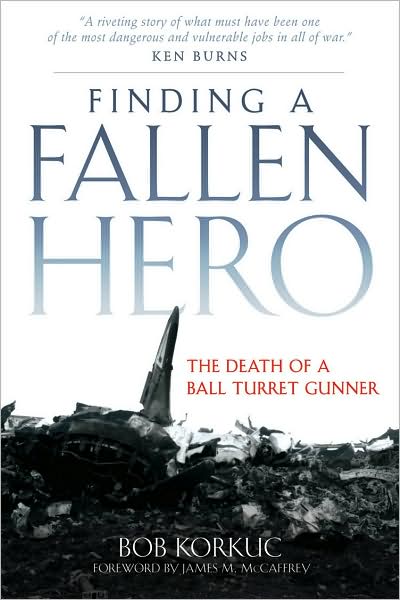

“Finding a Fallen Hero: The Death of a Ball Turret Gunner” by Bob Korkuc; University of Oklahoma Press; cloth; 256 pages; $24.95.

“Finding a Fallen Hero” by Bob Korkuc of Amherst tells the true story of how his uncle, Tony Korkuc, died in action during World War II.

Tony Korkuc was on duty as a ball turret gunner in a Flying Fortress B-17 when his plane went down near a small German village. The book describes what happened that sunny afternoon, what led up to the fateful flight and what followed. It also tells the story of Bob Korkuc’s seven-year quest to find the truth.

Like many books and all quests, this one started with a question. In 1995, Bob Korkuc and his father, Tony Korkuc’s younger brother, visited Arlington National Cemetery, where the family believed a marker commemorated Tony Korkuc’s death, his body having never been recovered. Yet the staff at the cemetery said Korkuc’s body was indeed interred in the cemetery, along with the bodies of two other crewmembers.

They wondered how the staff could be so sure those bodies were in Arlington when the family was equally sure Tony Korkuc’s bones lay somewhere in Europe.

Bob Korkuc, an electrical engineer, decided to find out. His quest stretched across the country and the seas, and at some point changed from curiosity to need. He needed to know. And as it turns out, so did his family.

How can any family come to terms with the loss of a loved one with so many questions unanswered? Questions such as:

• Was Tony Korkuc killed in the ball turret, hit by enemy fire, or did he die as a result of the plane crash?

• What caused the crash?

• Why did the pilot decide to leave formation, breaking a prime safety rule?

• What happened to the other crewmembers? Some died, Bob Korkuc knew, some became prisoners of war, but who were these men, the last to see Tony Korkuc alive?

• What was Uncle Tony really like as a man and as a soldier?

The more Bob Korkuc learned, the more his questions evolved and the more he wanted to know about the beloved uncle he’d never met, but who shared his nickname, “Korky.”

Ultimately, this is a detective story. One clue leads to another. Correspondence with officials at Mortuary Affairs and Casualty Support in Washington, D.C., leads to Air Force historical records.

Bob Korkuc discovers that Tony Korkuc was first buried by villagers in Willmandingen, Germany, but was moved to a cemetery in France and later to Arlington. What was up with that?

An Internet search turns up a Web site dedicated to the 381st Bomb Group, Tony Korkuc’s group. Joe Waddell, the group’s secretary, provides the names of the others on Tony Korkuc’s crew.

Now we’re getting somewhere! Bob Korkuc tracks down these men, one by one. Some are reluctant to talk. Some seem open at first, but then shut down on him. Some get angry: “I don’t believe you are aware of the cost to others,” or “stirring up the past.”

Bob Korkuc perseveres. He unearths old letters, photographs, military reports, even poems and spent cartridges. He uses these props to jar memories. He sorts out conflicting dates, faulty recollections, confusing records.

It sounds dry, I know, but somehow the mystery that drew Bob Korkuc to his uncle’s story also draws in the reader. When Bob Korkuc and his readers meet the survivors, hear their voices and their firsthand accounts, the story comes to life.

Nick DeRose served as bombardier on Tony Korkuc’s plane. He survived the crash and became a prisoner of war. He talked with Bob Korkuc about Tony Korkuc, about that last flight, about being a prisoner of war, about his mindset as a fighter, his attitudes toward the enemy and his role in defeating that enemy:

“My crew, we were on the first eight hundred and thousand plane raids. This is the thing. The British bomb at night, and they go home and go to bed. And then we come in the daytime. The Englishman would come up to you and say, ‘You fellows have bags of guts flying in the daytime.’ Boy, well, we used to think they had the bags of guts flying at night.”

Through colorful characters such as DeRose, Bob Korkuc takes readers to war in the most intimate way, through the memories of those who lived it. By writing in detail about one lost warrior, he honors many.

The message here isn’t that the government or individuals were trying to cover up the truth, but that in wartime the facts can get muddled in red tape, innocent mistakes or sloppy records that perpetuate misinformation. With hard work, though, the records can be reconciled.

An even greater message emerges, though. When families don’t know for sure what happened, they could still be waiting for their loved one to walk through the door 50 years later. Knowing provides closure. Not knowing hurts.

Bob Korkuc calls this pain “the tragedy of losing one’s past.” His long search for an important part of his family history finally leads him to the hill where Tony Korkuc’s plane went down. He videotapes the scene, then speaks into the camera:

“Dad, this is for you. In attempting to answer your question, this is where Tony’s plane crashed. This is where Uncle Tony died.

“When the moment at the crash site finally arrived, I was overcome with emotion. Nothing could have prepared me for what I was feeling. As I stood on the hill where my uncle took his last breath, I was moved by the historic and personal significance of the ground beneath my feet. I walked alone on the hill for awhile.”

Later, he speaks into the camera again. This time, he addresses his uncle:

“Tony, I have traveled halfway across the world to see the hill where you were killed. I want to let you know that I traced you from your final resting place at Arlington to the crash site. May you rest in peace.”

KORKUC, ANTHONY J

S/SGT AAF USA

BURIED AT: SECTION 34 SITE 1631

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard