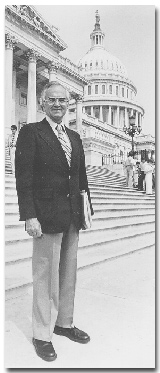

Courtesy of the U. S. House of Representatives:

FISHER, Joseph Lyman, a Representative from Virginia; born in Pawtucket,

Providence County, Rhode Island, January 11, 1914; attended public schools; B.S., Bowdoin College, Brunswick, Maine, 1935; Ph.D., economics, Harvard University, 1947; M.A., education, George Washington University, Washington, D.C., 1951; planning technician, National Resource Planning Board, 1939-1942; economist, United States Department of State, 1942-1943; teacher and lecturer at various universities; served in the United States Army, 1943-1946; senior economist, Council of Economic Advisors, 1947-1953; president, Resources for the Future, Inc., 1953-1974; elected as a Democrat to the Ninety-fourth, Ninety-fifth and Ninety-sixth Congresses (January 3, 1975-January 3, 1981); unsuccessful candidate for reelection in 1980 to the Ninety-seventh Congress; Virginia secretary of human resources, 1982-1986; professor of political economy, George Mason University, 1986-1992; was a resident of Arlington, Virginia, until his death there on February

19, 1992.

Faith in Action

by George Kimmich Beach, Unitarian Universalist Minister

When he affiliated with the Unitarian Universalist faith, Albert Schweitzer characterized it as a way of “faith in action.” Joseph and Margaret Fisher—Joe and Peggy, as we have always called them —exemplify what Schweitzer had in mind. Their spiritual and moral convictions have undergirded a lifelong engagement in the civic, religious, and professional institutions of their community and world. Religion for them has always meant “faith in action.”

Peggy Fisher first used the term “living religion” in her outline for a young people’s course on Unitarian Universalist beliefs that she and Joe taught in their home congregation. For a living religion, she suggested, the Unitarian Universalist flaming chalice is an apt symbol: an inner light that inspires caring and active service.

Joe and Peggy Fisher have reflected deeply on the meaning of their activism. In the poetry and the essay-sermons here published for the first time, they have shaped their reflections into a vision of public and personal life. As Peggy notes in her Preface, she and Joe initially outlined the series and set to work. Their outline was enlarged to accommodate new themes as they emerged. The book reflects the Fishers’ original plan: to begin by setting forth the theme of the whole series (“Religion and Living”), and to conclude with a review and a call to commitment (“Religion and the Future”). The project took more than fifteen years to complete.

I asked them why they had undertaken such an ambitious project. They wanted, they said, to create together religious services for their own and other congregations. They wanted to draw upon their experience, relating religion to life as a whole. Especially, they wanted to give strong, affirmative expression to their liberal faith. With their rich store of familial, professional, and voluntary experience, none have been better qualified for such a task.

Margaret Winslow and Joseph Fisher met on a blind date, in her home town, Indianapolis, on January 1, 1941. She was a sophomore at Wellesley College; he had begun graduate studies in economics at Harvard University. It was a whirlwind romance: in April Joe proposed; a little more than a year later, on June 27, 1942, they were married.

Joe was then working for the National Resources Planning Board, in Alaska. (From the outset of his career serving “the public interest” was his guiding ideal.) Peggy transferred to Reed College in Portland, Oregon, to be with Joe, whose office was moved to that city following the Japanese attack on the Aleutian Islands during World War II. The Fishers’ first year of married life was spent in Portland, where Peggy completed her Bachelor’s degree in French literature. Their first son was born four months after her graduation and just two weeks before Joe left for military service in the Pacific theater. At Pearl Harbor Joe first worked on the logistics staff of Admiral Nimitz. When that work was completed, he transferred to the Army newspaper, Stars and Stripes, as an editor. He remained in this position until the end of the war.

Joseph Lyman Fisher was born in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, in 1914, one of two children in a Unitarian family. A trim athlete, he was a skillful boxer and an avid wilderness hiker and canoeist. He enrolled at Bowdoin College, in Brunswick, Maine, graduating in 1935, and began his career as an economist specializing in resource management. After the war, the Fishers moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where Joe continued graduate studies in economics, receiving a doctorate from Harvard University in 1947. The growing Fisher family then moved to the nation’s capitol, living in Falls Church initially and in Arlington a little later. From 1947 to 1954 Joe was Executive Officer and Senior Economist of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers. From 1954 to 1975 he worked for a private research and educational foundation, Resources for the Future, Inc., becoming its President in 1959.

Politics was a natural extension of his civic activism. A Democrat and a leader in Arlingtonians for a Better Community, a liberal political coalition, Joe was elected to the Arlington County Board, on which he served for a decade, including two terms as Chairman. During his political career he also served as the Arlington representative on the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments and as member of the board of the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority; for both he also served as Chairman.

Joe’s greatest political triumph came in 1974 when he upset the eleven-term Republican incumbent, Joel Broyhill, in the 10th Congressional District of Virginia. In the House of Representatives Joe soon established himself as a respected expert on economic policy. By 1980 his original political base in Arlington County had been diluted by a burgeoning Republican majority in western Fairfax County; in the year of “the Reagan revolution” he lost his bid for reelection to Congress.

A staunch but never a doctrinaire liberal, Joe Fisher had made a lasting mark on national and state politics. Richard Pearson noted highlights of his career in an obituary article in the Washington Post (February 20, 1992):

“Mr. Fisher was named to the powerful House Ways and Means Committee, and soon made a reputation for his work on taxation, energy and budget policy, and he was chosen by his committee chairman to coordinate seven task forces that drafted the energy program that emerged from several congressional and White House proposals. In 1982, Mr. Fisher joined the cabinet of Gov. Charles S. Robb as Virginia’s secretary of human resources, a post in which he was responsible for a $3.5 billion budget and 20,000 employees in 15 agencies. Although he took office at a time of economic retrenchment, he received favorable reviews from critics spanning the political spectrum.”

Joe remarked to me that the complexity of social needs and political pressures made being Secretary of Human Resources for the Commonwealth of Virginia the most difficult job he had ever had. Yet far from avoiding large responsibilities, he relished them. The depth of his knowledge of contemporary social problems and his commitment to effective public programs to address them is evident. Looking back upon his public career, he took the greatest pride from his contributions to federal environmental policy and his successful role in creating the Bill of Rights for handicapped persons in Virginia.

Education played a large part in Joe’s and Peggy’s lives, extending their vocational identities. Together they enrolled in the master of arts in Education program at George Washington University. A 1952 graduation photo shows Joe and Peggy standing with the Dean, Peggy’s “second pregnant commencement” barely disguised by her academic gown.

During these and subsequent years Peggy and Joe were raising three daughters and four sons. With a husband so deeply involved in civic life, many of the burdens—and the joys, she adds—of raising the family fell to Peggy. (Joe “uncomfortably” recalls the answer one of their grade-school age daughters gave to a teacher’s question to the children about what their fathers did for a living. She said, “My daddy goes to meetings.”) Nevertheless, Peggy found time to establish her own career as an artist, an arts educator, and a poet.

When Joe’s work took them to the capitol of Virginia, Peggy entered Virginia Commonwealth University, in Richmond. There she earned a bachelor of fine arts degree, refining her skills as a painter and a teacher of painting. She has taught painting at the Northern Virginia Community College and the University of Virginia, and in the adult education program in Arlington. For Peggy teaching art is a humanistic endeavor; in her words, it is a way to “help people realize their potential for creativity.” She adds, “and people are never too old to learn.”

Her own landscapes, figure paintings, and family portraits, in both oil and watercolor, are vibrant with color and feeling. Her art reflects the places she has lived or visited—including Greece, Indonesia, Italy, China, Ecuador, Mexico, and Columbia. Most often they reflect her deep feeling for her “home base”—in Arlington and at their family retreats in Loudoun County and Maine. Her poetry exhibits similar qualities: clear, forceful expression of perceptions and deeply felt values. She addresses the reader in her personal voice; thus her poetry challenges us and evokes a personal response. She has received awards from the New York Poetry Forum and the National League of American Penwomen, in which she has been an organizational leader.

A conservationist in her several communities, Peggy has served as member and chair, since 1989, of the Goose Creek Scenic River Advisory Board (to which she was appointed by three Virginia governors), founding member of the Arlington Beautification Committee, and member of the board of the Preservation Society of Loudoun County and Keep Loudoun Beautiful. Her civic and artistic achievements have been recognized in several awards.

The partnership of Joe and Peggy Fisher has also been expressed through their religious community, the Unitarian Church of Arlington, where they have been active members and leaders from its inception, in 1947. When their children were young, they taught Sunday school classes. Joe was elected Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the church, and later, to the Board of the Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA). When the position of UUA Moderator was suddenly vacated, creating a leadership crisis, Joe was selected by his peers to fill the position. He was subsequently elected by the national membership to two more four-year terms.

In 1985 Joe’s severe back pains were diagnosed as bone cancer. Through treatment he gained remission and relief from pain, enabling him to maintain the extraordinary round of political, civic, recreational, and familial activities that marked his entire adult life.

After Joe and Peggy returned to Arlington from Richmond in 1986, Joe was appointed Distinguished Professor of Political Economy and special adviser to the President of George Mason University. He taught classes and kept up a busy round of engagements until late in 1991. Shortly before his death the University announced the inauguration of the Joseph L. Fisher Fellowship Endowment Fund in Public Policy, to support students in The Institute for Public Policy. Kingsley E. Haynes, Dean of the Graduate School, noted the qualities that had led so many institutions to turn to him for leadership:

“Joe” Fisher embodied the best characteristics of academic perspective and hands-on public service, both as a participant in the legislative process and as a member of the executive. He has a special combination of calm and stability in very difficult situations as well as a powerful commitment to change and adaptation. He served as an elected and appointed official at all levels of government and was appreciative of the critical role of governmental personnel. He was an outstanding teacher and a skilled adviser in both the analytical and political arenas.

In his last public address, in October, 1991, as Honorary Co-Chair, with Peggy, of the Building Campaign of the Unitarian Church of Arlington, Joe urged the congregation, “Go for it!” He had given himself the same advice for a lifetime.

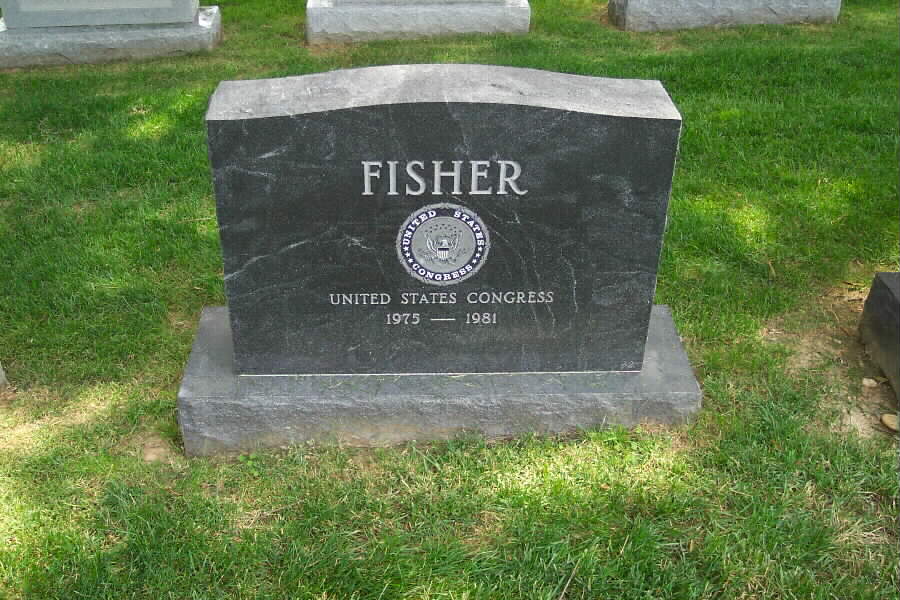

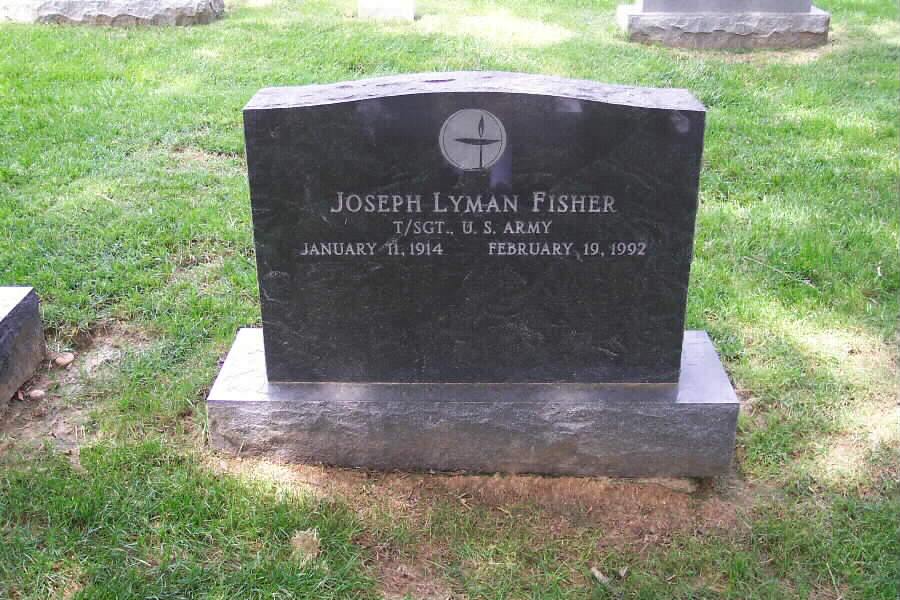

His memorial service at the Unitarian church was attended by an overflow crowd, the largest number in its history. A few days earlier, family members and close friends gathered at Arlington National Cemetery to offer final appreciations—words, music, a brief dance. There his ashes were buried, next to the graves of two four-star generals. The marker reads: “Tech Sgt. Joseph L. Fisher, Member of Congress.”

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard