One of the most colorful soldiers ever to serve in the United States Army. Although the Indian Wars were over, he would rise still higher, to the top command in the U.S. Army.

It was an impressive ascent from youthful beginnings as a clerk in a Boston crockery store, but still not as high as his ambition dictated. His future career, like his past, would be marred by controversy and endless discord with associates. For in him vanity and ambition powered a fierce competitiveness that drove his to revel tastelessly in his own genuine abilities and successes while minimizing or denying those of others. “Brave peacock,” Theodore Roosevelt would call him, not inaccurately.

Unfortunately for his place in history, the image obscured a record of notable achievement. He came to the frontier army in 1866 without West Point credentials but with an extraordinary Civil War record.

Self-education had prepared him for the war. While clerking in Boston, he had attended night school, read deeply in military history, mastered military principals nd techniques, and even paid an old French veteran to teach him to drill. He marched off in 1861 as a First Lieutenant of Massachusetts Volunteers. Courage, leadership, professional knowledge, hard work and ambition brought the young officer to notice of his superiors, and he rose swiftly. By Appomattox, he had made himself a popular hero, four times wounded, veteran of every major battle of the Army of the Potomac except Gettysburg, successful regimental, brigade, division and (briefly) corps commander.

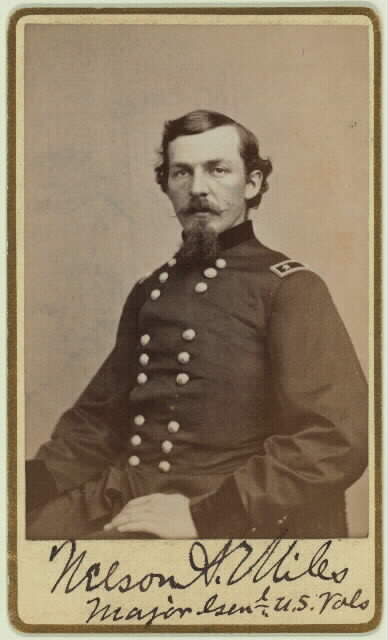

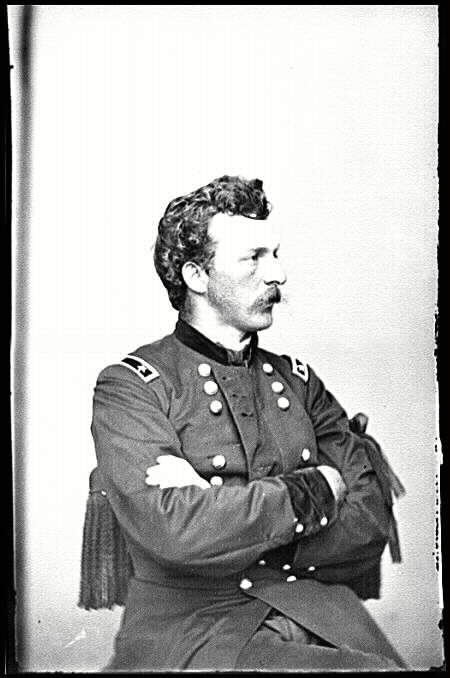

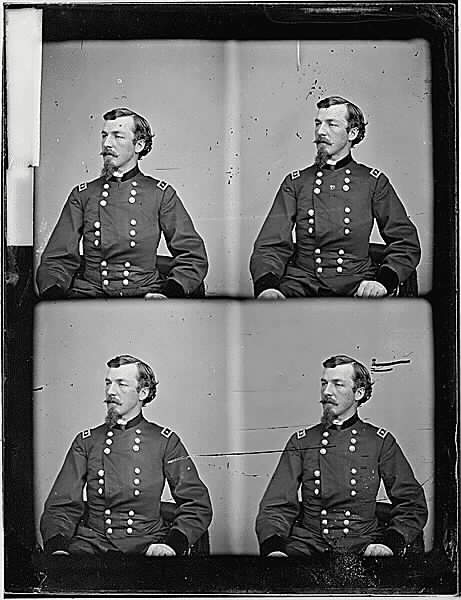

Promotion to Major General of Volunteers came in October 1865 and three brevet promotions covered him with further honors. Not only was he a genuine hero, he looked like one. Tall, muscular, broad-shouldered, well-proportioned, with intense blue eyes and a jaunty mustache, he made a dashing figure in his blue and gold uniform with starred shoulder straps and chest full of brass buttons.

He was 26 years old. He had found his calling. He wanted to be a career soldier and his record in the Volunteer Service assured him a commission in the post-war regular army. He sought a brigadier’s star, a presumptuous goal in the shrunken peacetime army, even for one of his conspicuous attainments. The colonel’s eagles that he accepted with bad grace represented a higher rank than others with even greater distinction and seniority could win. Even this distinction cam not solely in recognition of his wartime services. He had learned one of the truths of his times: ability helped, but high-level influence was vital. He enlisted the support of an imposing roster of military and political luminaries in behalf of his candidacy, and his colonel’s commission owed as much to this as to his war record. He would become one of the army’s most ardent practitioners of influence peddling. Marriage appeared to enhance his possibilities, although it is unlikely that cynicism formed part of that motivation.

On June 30, 1868, he married Mary Hoyt Sherman, whose uncles were Ohio Senator John Sherman and Army Major General William Tecumseh Sherman. Less than a year later, with the inauguration of Ulysses S. Grant as President of the United States, Sherman became General-in-Chief of the Army. At once, Miles began to importune his wife’s uncle for official favors. Until 1883, when he stepped down as leader of the Army, Sherman stubbornly fended off these efforts.

As early as 1888, California interests had advanced Miles’ name for the presidency, and throughout the 1890s he doubtless had no more difficulty visualizing himself as President than he had in 1876, a frontier Colonel, as Secretary of War. In truth, neither major party ever seriously considered him a serious nominee. In 1895, he did attain the top command of the Army, successor to Washington, Scott, Grant, Sherman and Sheridan, but his term was filled with frustration.

In the Spanish-American War, William McKinley denied him any real authority and relegated him to command an almost unnoticed expedition against Puerto Rico. Instead of glory, he gained uncomplimentary notice from a bitter public quarrel with the Secretary of War and a ruthless, unjust attack on the Commissary General of the Army in the scandal over “embalmed beef.”

Even his elevation in 1901 to the newly restored grade of Lieutenant General brought only small satisfaction. Almost at once he earned the displeasure of Theodore Roosevelt by taking sides in a feud between admirals and by criticizing U.S. policy in the Philippines. He also opposed the long-overdue reform of the War Department, which called for converting the Commanding General to a Chief of Staff. Finally, when he reached the mandatory retirement age of 64 in 1903 and stepped down as the last Commanding General in the Army’s history, the President declined to send the customary congratulatory message, and the Secretary of War did not attend the retirement ceremonies.

He lived out his remaining years quietly in Washington, D.C. World War I brought persistent application for active duty, but they were politely turned aside. No longer a center of controversy, he became a venerable figure out of the past, a reminder of the war to save the Union, out of the old army, and of the frontier West that he played such a glorious part in opening to settlement.

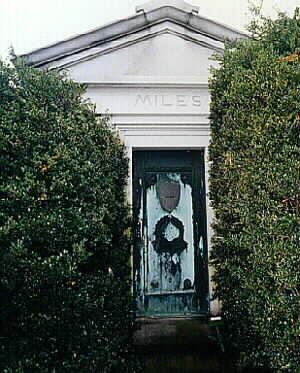

The end, at the age of 85, could not have been more fitting. In the spring of 1925, he took his grandchildren to the circus. The band played the National Anthem. Standing erectly at attention, rendering the military salute to the flag, he collapsed with a heart attack. The burial at Arlington National Cemetery featured the impressive ceremonial homage he would have considered his due. He might have also felt a small sense of vindication in the gravesite attendance of President Calvin Coolidge. He is buried in Section 3 in one of only two mausoleums in Arlington National Cemetery (the other in Section 1 belongs to General Thomas Crook Sullivan). Another connection with Arlington was that Miles was the Grand Marshall at the dedication of the Memorial Amphitheater, which was held in 1920.

He was born on August 8, 1839 near Westminister, Massachusetts. He was commissioned as Captain of the 22nd Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry at the outbreak of the Civil War. His baptism of fire came while serving in General Oliver O. Howard’s staff at Fair Oaks (Seven Pines), May 31, 1862, after which his bravery earned him promotion to Lieutenant Colonel. He was promoted to Colonel after assuming command of his regiment in the midst of the battle of Antietam (Sharpsburg), September 17, 1862. Distinguished himself and was himself seriously wounded at Fredericksburg, December 13, 1862, again at Chancellorsville, May 2-4, 1863. For his actions at the latter he won, as of March 1867, Brevet to Brigadier General and even later, in 1892, the Medal of Honor. He was present at nearly every major engagement of the Army of the Potomac.

Appointed Brigadier General of Volunteers in May 1864 and commanded a Division in the final campaign at Petersburg, Virginia. In October 1865, at the age of 26, was named Major General of Volunteers in command of II Corps. As commandant of Fort Monroe, Virginia, after the war, he became the custodian of Jefferson Davis, and for keeping him shackled in his cell, was the target of severe public criticism, even in the North. In July 1866 was appointed Colonel in the regular army and in March 1869 was commander of the 5th U.S. Infantry. His subsequent service on the Western frontier was dedicated and courageous during recurring hostilities with the Indians. Achieved victories against Cheyenne, Comanche, Kiowa and Arapaho on the Staked Plains of Texas in 1874-75, notably the victory of Colonel Ranald S. MacKenzie at Palo Duro Canyon, September 24, 1874, and later was instrumental in driving the Sioux under Sitting Bull into Canada nd pacifying those under Crazy Horse. He captured Chief Joseph in 1877 after the Nez Perces incredible march toward sanctuary in Canada, and the following year pacified the Bannocks under Chief Elk Horn near Yellowstone. Promoted to Brigadier General in December 1880, he commanded the Department of the Columbia until 1885 and the Department of the Missouri in 1885-86, and in April 1886 succeeded General George Crook as the commander of the Department of Arizona, where he succeeded in September in finally capturing the elusive Apache leader, Geronimo. He commanded the Department of the Pacific at San Francisco in 1888-90, receiving promotion to Major General in April 1890. In the last uprising of the Sioux in South Dakota in late 1890, during which Sitting Bull was killed, he restored U.S. control over the Indians, but his reputation was permanently tarnished by the massacre of some 200 Sioux, including women and children, by troops under the command of Colonel James W. Forsyth (7th U.S. Cavalry) at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, on December 29, 1890. In 1894, while commanding the Department of the Missouri, was responsible for the Federal troops employed in the suppression of the Pullman strike disorders in Chicago. Was placed in command of the Department of the East, with headquarters at Governors Island, New York in 1894, and on the retirement of John M. Schofield be became on October 5, 1895 the Army’s Comander-in-Chief. His role in the Spanish-American War was mostly administrative, although the did conduct an expedition to Puerto Rico, landing on July 25, 1898, and campaigning until August 13. In February 1901 he was promoted to Lieutenant General. Late in that year he was reprimanded for having commented publicly on Admiral George Dewey’s report on charges against Winfield Scott Schley. In 1902, on his return from an inspection trip in the Philippines, he aroused controversy with his criticism of the conduct of certain U.S. officers there. Author of “Personal Recollections and Observations of General Nelson A. Miles,” in 1896, and “Serving the Republic,” in 1911.

MILES, NELSON A.

Rank and organization: Colonel, 61st New York Infantry. Place and date: At Chancellorsville, Virginia, 2_3 May 1863. Entered service at: Roxbury, Massachusetts. Birth: Westminster, Massachusetts. Date of issue: 23 July 1892.

Citation

Distinguished gallantry while holding with his command an advanced position against repeated assaults by a strong force of the enemy; was severely wounded.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard