From a press report: March 1997

Brian Kent McGar left Modesto a generation ago, a mystery in the making, a teenager bound for war.

Now, prompted by high-tech tools, the South Vietnamese earth has yielded some final answers about the soldier called Kent. And in two weeks, his remains will be set, for good, in the peaceful, storied folds of Arlington National Cemetery.

“I never expected it,” said Kathy Plummer, one of McGar’s two sisters. “When we first got the news, that was a slap out of the blue.”

Disappointment, frustration and unanswered questions — that’s what Plummer and McGar’s other sister, Kerry Gwin of Modesto, had come to expect since their brother’s disappearance on May 30, 1967. They also have had to cope with an Army that let an outrageous error fester in archived records and a search that seemed to go nowhere.

For years, McGar had remained one of more than 2,000 Americans listed as unaccounted for from the Vietnam War.

Though the McGar family wouldn’t learn the details for several years, in January 1994 investigators began turning over a sweet potato field in Quang Ngai Province. Using trowels to dig the earth and screens to sift it, guided by ground-penetrating radar and the memories of a former Viet Cong guerrilla, investigators uncovered the clues they needed over a two-week period:

Bone fragments. Eighty-six teeth, enough for three men. The sole of a left boot, size 10. A tarnished brass belt buckle, a zipper, and five steel-tipped bullet fragments.

Mere remnants. But they were sufficient for the government scientists who, working in a Hawaiian lab, painstakingly closed in on the identities of three young men:

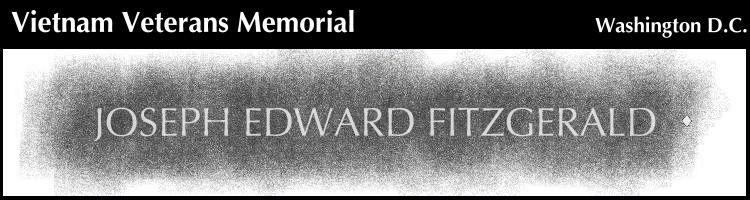

Private First Class Joseph Fitzgerald. Sergeant John Jakovac.

And Brian Kent McGar, a private first class who had enlisted in the Army after leaving Ceres High School as a junior. Good with a rifle and mechanically adept, but not spit-shined to perfection, he worked in supply for many months.

Then he voluntarily extended his year-long tour and joined the Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol in the 25th Infantry Division’s 3rd Brigade.

“That is very much a puzzlement to us all … why he went back,” Plummer said.

Thirty years ago, McGar and his fellow LURPs set out for an observation post on Hill 310 in Quang Ngai Province. They were last heard from about 8:30 p.m. on the night of May 30. The next day, U.S. soldiers found the bodies of two LRRPs, spent ammo and a trail of blood. Of McGar, Fitzgerald and Jakovac, there was no sign.

“This one was a real mystery; I never thought that we’d get those three back,” said Lynn O’Shea, a New York City bookkeeper who’s immersed herself in the intimate details of the McGar case.

O’Shea is a skeptic; she still wonders, for instance, how it was that searchers could have missed the McGar gravesite for so many years. But skepticism, and sometimes deep bitterness, is common among families of the missing. McGar’s mother, for one, simply stopped talking to Army officials several years ago.

There are 2,128 Americans still unaccounted for from the Vietnam War. In some cases, family members — hoping against hope, or perhaps burned by past experience — have refused to accept the military’s assertion that remains have been identified.

“I’m always leery of these things,” Plummer said, “but I couldn’t deny all the circumstances.”

Scientists obtained DNA samples by grinding up some of the bones, and then took blood samples from surviving family members. It was a good match between the DNA from one of the bones and the DNA in the blood of McGar’s mother, Charlene. There was other, circumstantial, evidence as well, that a nervous mortuary affairs official presented to Gwin and Plummer at a briefing in Winnemucca last February.

For years, an Army report remained uncorrected in the National Archives, asserting that “McGar’s sister was killed in a mortar attack on Cu Chi Base, and he had sworn to kill one (Viet Cong) for every year of her life.”

The statement was wrong in every respect. But Army officials declined to delete it, or at least insert a correction, until contacted by a reporter several years ago. Since then, a follow-up letter has been added to the files.

Funeral services are to be held April 9-10. Plummer and Gwin will be there. So will O’Shea, the families of Jakovac and Fitzgerald, and some aging soldiers.

“At the briefing, I was just listening to the facts; it was almost like business,” Plummer said. “When we started making burial arrangements, that’s when it got a little tougher. I think the worst is yet to come. The funeral service, that’s pretty final.”

From a press report: April 10, 1997

An April wind blew cold comfort and the sound of taps across Arlington National Cemetery Wednesday, as soldiers young and old buried a son of Ceres, who will always be 19.

It was the young soldiers from the 3rd Infantry Division, precise in their funereal movements, who lowered a portion of Brian Kent McGar’s remains into a common grave to be shared with two others.

It was the aging soldiers, the gray and flagging ones, who reclaimed their badges and their camouflage once more to honor three Americans whose remains were lost for nearly 30 years.

It was the women, sisters Kerry Gwin and Kathy Plummer, who accepted the American flag presented by a chaplain murmuring his condolences over the teen-ager everyone called Kent.

“He was just a kid,” Gwin said, “and he went over and did what he thought he was supposed to do.”

He died in a 1967 ambush. But McGar’s remains weren’t found until 1994, and he wasn’t positively identified for family members until this year.

Gwin now lives in Modesto, where she works for the telephone company. Plummer lives in Nevada, where she manages a motel and casino. Their mother is so bitter at the Army’s handling of her son’s case that she did not attend the service.

“Let me tell you,” said Joann Lambert, sister of one of the other men buried Wednesday, “it’s been one catastrophe after another.”

Then Lambert amended her statement. The Army’s enlisted men have been superb, she says; and, for all the past screw-ups, most of the memorial preparations have been deftly handled. Gwin and Plummer, listening, don’t disagree.

The Army choreographs impeccable funerals, the fruit of long practice. McGar’s began with a reception at the Fort Myer NCO Club, for the three families that still remain mostly strangers to one another despite their common loss. A hawk-eyed colonel from the U.S. Special Operations Command, resplendent in jump boots and combat ribbons, paid his respects.

McGar was a special operations soldier, of a sort. After enlisting in the Army out of Ceres High School, he volunteered for a second tour in Vietnam. Then he volunteered again, for the 25th Infantry Division’s Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol. It was a long way from his San Joaquin Valley roots.

“He was like any other kid in small-town America,” said Ceres mail carrier Walt Butler, a Navy veteran and friend from grade school days.

On the night of May 30, 1967, Pvt. First Class McGar, PFC Joseph Fitzgerald and Sgt. John Jakovac disappeared while on their way to an observation post in Quang Ngai Province. They were the only soldiers in the short life span of the Long Range Reconnaissance Patrols whose ambushed bodies weren’t quickly recovered.

“Theirs were names that were written on plywood walls,” said Dan Nate, recalling how the soldiers’ memory was kept alive in Vietnam by their comrades.

Nate arrived in South Vietnam about three months after McGar disappeared. He and his compatriots kept their eyes peeled for signs of the missing three; there were none. Now, Nate is a 49-year-old, laid-off Philadelphia Naval Shipyard worker. Bearded and ponytailed, he sports a blue star in his left earlobe and a Combat Infantryman’s Badge in his lapel.

Nate and about a dozen other veterans formed their own honor guard at the service. Their aging bodies remembered attention as the rifles volleyed, as a trumpeter played taps, as the chaplain intoned the 23rd Psalm. Defense Department officials, and Nate himself, called the ceremony closure.

But Gwin said, “I hate that word.”

She’s not bitter. The war was a long time ago; so was McGar’s death. She leaves to others the lingering obsessions, the silver POW MIA bracelets. But she does have her anger, about the Army’s stubborn refusal to correct her brother’s publicly available file. The file falsely asserted McGar sought revenge because the Viet Cong killed his sister. The source of the false report is unclear; McGar didn’t have a sister who was killed in Vietnam.

It took years before the Army would amend the file.

Today, Plummer and Gwin are attending a separate Arlington burial service for McGar. It will lack the pomp and circumstance of Wednesday’s service. But they’ll be joined by Walt Butler, who for eight years has worn a bracelet with McGar’s name. Now he’s removing the bracelet for good; though what he’ll do with it, he’s not yet sure.

“He’s a friend,” Butler said, when asked why he’s making the funeral trek. “He’s somebody I grew up with that didn’t come back. It’s something I had to do.”

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard