The youngest man ever to be elected to our nation’s highest office, he had served as a United States Naval Officer in the South Pacific during World War II and there commanded the PT-109. During an attack by a Japanese cruiser, he is credited with saving the lives of his crew. On his return home following the war he was elected to the United States House of Representatives from Massachusetts and later to the United States Senate from that state. He was elected to the Presidency in November 1960, defeating then-Vice President Richard M. Nixon by one of the smallest margins in history. He was assassinated in Dallas, Texas, on November 22, 1963 as he rode in an open motorcade in that city. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery on November 25, 1963 and his gravesite is one of the most visited spots in the cemetery. He was moved from the original gravesite to one just a few feet away on March 14, 1967. His wife, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis was laid to rest next to him when she died of cancer in 1994.

His infant daughter (who was not named) and who was born and died on August 23, 1956 is also buried in his gravesite as of December 4, 1963. She was originally buried in Newport, Rhode Island.

An infant son, Patrick Bouvier Kennedy (August 7, 1963-August 9, 1963) who was born prematurely and who was originally buried at Brookline, Massachusetts, is also buried in this site as of December 4, 1963.

Gravesite Inscription:

Let the word go forth

From this time and place

To friend and foe alike

That the torch has been passed

To a new generation of Americans.

Let every nation know

Whether it wishes us well or ill

That we shall pay any price – bear any burden

Meet any hardship – support any friend

Oppose any foe to assure the survival

And the success of liberty

Now the trumpet summons us again

Not as a call to bear arms

– though embattled we are

But a call to bear the burden of a long twilight struggle

A struggle against the common enemies of man Tyranny – Poverty – Disease – and War itself

In the long history of the world

Only a few generations have been granted

The role of defending freedom

In the hour of maximum danger

I do not shrink from this responsibility

I welcome it

The Energy – the Faith – the Devotion

Which we bring to this endeavor

Will light our country

And all who serve it

And the glow from that fire

Can truly light the world

And so my fellow Americans

Ask not what your country can do for you

Ask what you can do for your country

My fellow citizens of the world – ask not

What America can do for you – but what together

We can do for the freedom of man

With a good conscience our only sure reward

With history the final judge of our deeds

Let us go forth to lead the land we love – asking His blessing

And his help – but knowing that here on earth

God’s work must truly be our own.

Inaugural Address – January 20, 1961

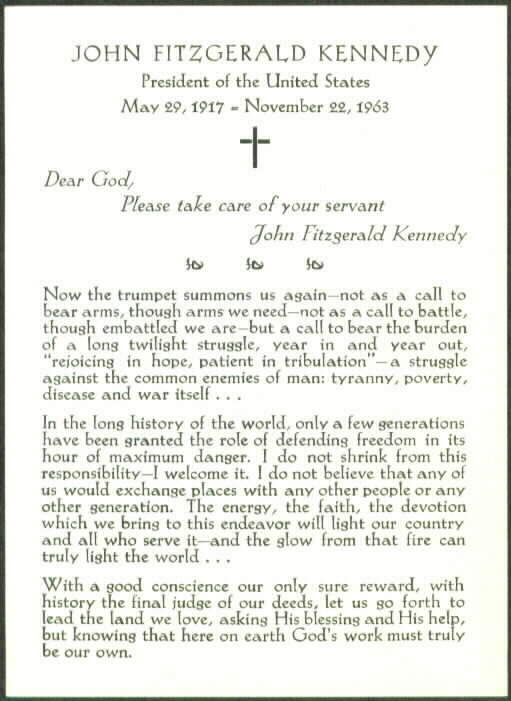

Prayer Card From The Funeral of John F. Kennedy

From the Collection of Michael Robert Patterson

Man of the year,

1961

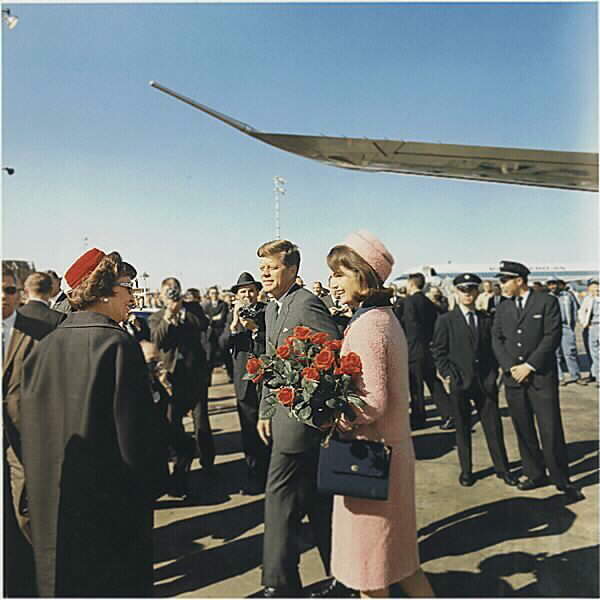

President & Mrs. Kennedy arrive

at Love Field, Dallas, Texas,

November 22, 1963

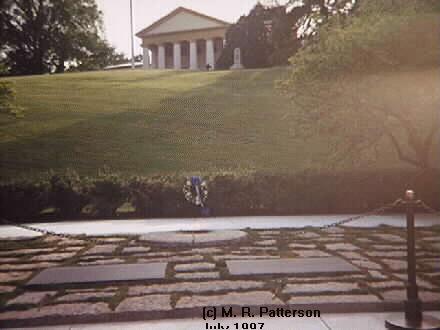

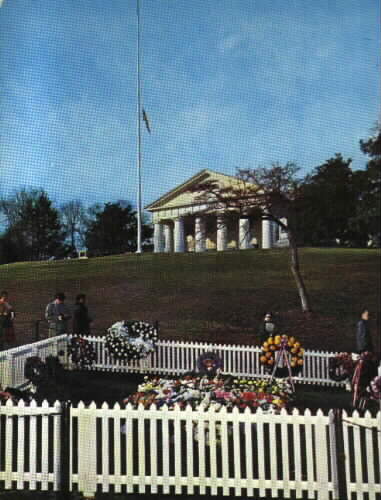

John F. Kennedy gravesite with the Custis-Lee Mansion in the background.

Photo courtesy of my son, Brian Patterson, May 1997

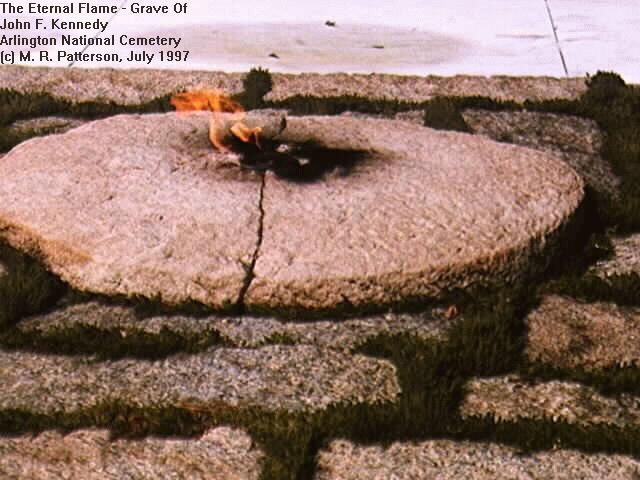

The Eternal Flame at the John F. Kennedy Gravesit

November 22, 2000

President Kennedy laid to rest; The Times, 26.11.63

from our own correspondent

From The Times, Tuesday November 26, 1963

November 22, 2000

President Kennedy laid to rest; The Times, 26.11.63

from our own correspondent

Tuesday November 26, 1963

Kings and silent crowds pay homage

Screen of secret servicemen guard Mr. Johnson’s car

The remains of John Fitzgerald Kennedy, thirty-fifth President of the United States of America, killed by an assassin’s bullet, were laid to rest today in the Arlington National Cemetery.

He joined a great company of men who had fought and died in every American conflict from the Revolutionary War, because he first served his country as a junior naval officer in the distant Pacific. This was his right as a warrior of the Republic, but today’s solemnities were unprecedented in American presidential history; from all over the globe kings, presidents, and representatives of hundreds of millions of people came to honour the passing of the young man who had won the world’s most powerful elective office with a bare handful of votes and transformed it into a great power for peace.

OBSCURE ORIGINS

There are, no doubt, other great and good men no less anxious for peace, but it is the power and the glory of this Republic that at this moment in history only its President and Commander-in-Chief has the required authority. Mr. Kennedy also had the will, and if it was first shaped in some obscure Irish town it is the further glory of the United States that made possible the elevation from a Boston tenement to the White House.

The presence of Mr. Mikoyan, First Deputy Prime Minister of the Soviet Union, and an Armenian of equally obscure origins, was a reminder that the late President and Commander-in-Chief, who controlled the most dreadful weapons of destruction, took the first purposeful and successful steps towards disarmament. The Soviet presence was a fitting epitaph.

If this perhaps crossed the minds of some of the great present today, for millions of Americans the sorrow and despair was more personal. This day, November 25, did not begin anew in spite of the evidence of the clocks. All through the bitterly cold night a vast crowd waited patiently to pay homage as the remains lay in the great Rotunda of the Capitol. Midnight was meaningless.

IN THE SHADOWS

Some time during the night Mrs. Kennedy, accompanied by Mr. Robert Kennedy, the Attorney-General, came back once again to pray for her husband. The pride of family did not demand of her this time to bring the children. Her favourite Kennedy brother, who in happier times shielded her from the ebullience of the family, stood back in the shadows, among them the long shadows of the statues of other assassinated Presidents, Lincoln and Garfield. The slow-moving columns of mourners came to a halt.

When this last personal communion was over, she arose, still beautifully impressive and dry-eyed, and looked wonderingly into the eyes, some blinded with tears and others merely curious, of those waiting people. Then slowly and indomitably she walked down the steps with her fair-haired brother-in-law.

CROWDING MEMORIES

In the cold night air she at first dismissed her car and began to walk down Pennsylvania Avenue, along which less than three years ago she had ridden in triumph with her husband after his inauguration. Perhaps the memories came crowding too much, perhaps the uselessness of this last visit became apparent; silently the black car came up again, surrounded by watchful Secret Service agents, and she was gone.

When dawn came up over the Potomac, tens of thousands were still waiting outside the Capitol to pay their last respects. They had begun to move through the Rotunda at about 6,000 an hour, but the queue still lengthened; it stretched for more than an mile at one time, and the pace was doubled.

At nine o’clock – perhaps soon after the President’s son, John, had awakened for his third birthday – the great gates of the Capitol were closed. There were protests, and scuffling, but the police soon put an end to the unseemliness.

SENATE’S SYMPATHY

The sad ceremonial began today soon after 10, on a very cold but brilliantly sunny morning. Inside the gleaming white Capitol the Senate had met briefly to pass a resolution of sympathy for Mrs. Kennedy; outside, the reds and blues and blacks of the cortege arranged themselves on the broad plaza.

At 10.22 Mrs. Kennedy emerged from the White House accompanied by her brothers-in-law and sisters-in-law, her nephews and nieces. The seven great black cars made their way down the broad expanse of Pennsylvania Avenue through silent crowds whose predominantly youthful character spoke much about the late President.

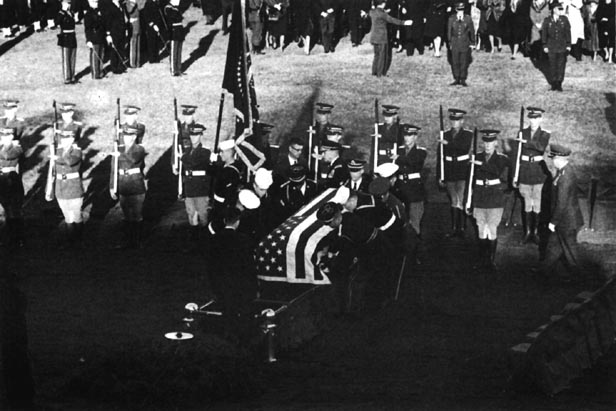

Fifteen minutes later Mrs. Kennedy, lightly veiled, walked slowly up the huge white steps between her husband’s brothers, Robert and Edward, and into the Capitol Rotunda where they knelt for a moment, before the great bronze casket containing the last earthly remains of her husband was carried out into the sunshine. Then out again into the chill morning air to watch the coffin, draped in the Stars and Stripes, borne out by nine men of the services. Arms presented, and “Hail to the Chief” played by the Marine band as the coffin came into view. And solemn music as it was borne slowly down the stairway to the heavy caisson.

At 10.50 the seven greys moved off – a brief pause while the procession formed, and then muffled drums and the lumbering caisson jolted slowly forward, casting its long shadow on the street.

It was a martial but dignified scene, with none of the arrogance of militarism. The Marine band leading stepped out bravely but with sadness in each heart. The Stars and Stripes fluttering slightly ahead of the caisoon, the presidential flag behind and a caparisoned horse, riderless, prancing.

Then to the White House where the concourse of famous men was waiting. Mrs. Kennedy dismounted and, behind the caisson, led the most distinguished company of dignitories ever assembled in the 187 years of this great Republic, come in honour of her young husband. She walked briskly, her brothers-in-law on either side, the new President behind. The representatives of the world followed, a phalanx arranged in the alphabetical order of their countries. The procession moved away to the funeral.

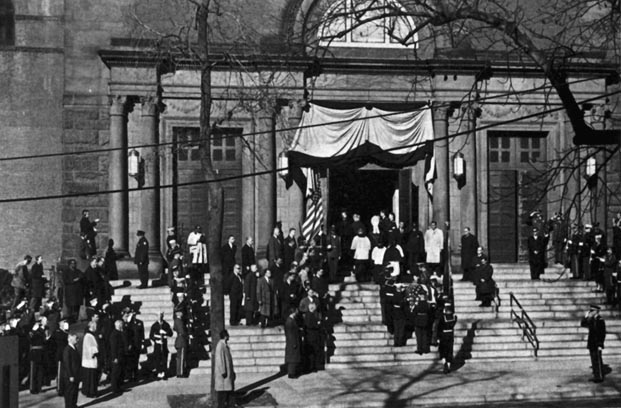

AT THE CATHEDRAL

At St. Matthew’s Cathedral, in the heart of Washington, Mrs. Kennedy led her two children up the steps of the cathedral, followed by members of the family, the President and Mrs. Johnson, crowned heads, elected heads of state of all races, creeds and customs. General de Gaulle, in uniform, a massive figure; Chancellor Erhard of Germany; the Emperor Haile Selassie; and the Duke of Edinburgh.

Nine pipers of The Black Watch, the regiment which played so recently for Mr. Kennedy on the White House lawn, led the march part of the way from the White House to the cathedral, lending further international flavour to the occasion and symbolizing the special relationship between Britain and the United States.

Sir David Ormsby-Gore, the British Ambassodor, had been asked to represent Sir Winston and Lady Churchill, and Mr. Macmillan was represented by the Duke of Devonshire, whose brother was married to a sister of Mr. Kennedy.

ADDRESS RE-READ

Cardinal Cushing of Boston, who was to conduct the Low Mass, led coffin up the aisle. It was 12.15. Mr. Luigi Vena, who had sung at Mr. Kennedy’s wedding, had come to sing the “Ave Maria” at his funeral. The Most Rev. P. M. Hannan, Auxiliary Bishop of Washington, read passages from the scriptures which the late President had used in his speeches, and finished by reading the entire inaugural address delivered in January, 1961.

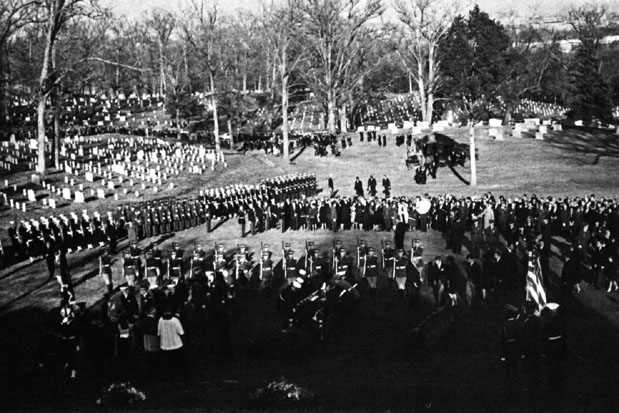

The service ended, Cardinal Cushing, in his brilliant orange robes, led the coffin from the church. Mrs Kennedy led her children out. As the band played “Holy God We Praise Thy Name”, little John, in a sky blue coat to match his sister’s, stepped forward for a moment and put his hand to his forelock as if in salute. And so almost an hour and a half after arriving at the cathedral, the slow procession moved away on the long drive to a grassy slope below the old Lee mansion, where President Kennedy’s grave will look down for as long as this Republic can expect, across the Potomac river to the Lincoln Memorial and the city he so completely dominated for so few brief years.

LAST FORMAL ACT

It was the last formal act of the tragedy that began in Dallas, Texas, three days ago, and after the prayers of the burial service there was nothing left to be said. The other branches of Amercan Government, the Congress and the judiciary, had delivered their eulogies, and it was left to the armed services to provide military honours.

The American forces are no less jealous of their prerogatives than others, but generous to the last the main military exercise, the reversing of arms was given to a troup of Irish Army cadets to perform. Their presence with that of the Black Watch pipers earlier, at the specific request of Mrs. Kennedy, was perhaps recognition not only of Mr. Kennedy’s origins but also of the first origins of this country.

The National Cemetery is part of a 5,000-acre tract granted in 1669 to one, Robert Howson, who sold it for six hogshead of tobacco. From the mansion above the President’s grave, built by the adopted grandson of George Washington, General Lee resigned from the Union army and rode off to command the Confederate forces in the war between the states. With all respect to the men who lie here, who gave their lives for the republic, an Englishman cannot but feel that some of his roots are here.

In a way, the history of decades was there today. The Emperor of Ethiopia, who appealed in vain to the League of Nations and is now secure in a world system that, in the final test, still depends upon this republic; the Duke of Edinburgh and the Prime Minister, President de Gaulle, the King of the Belgians, the Dutch Consort, and others representing the most powerful alliance for peace in the history of mankind because of the leadership provided by this republic.

The awful power that made all this possible was not much in evidence today. Fifty fighter aircraft, representing the components of the Union, roared overhead followed by Air Force No. 1, the Presidents’s personal aircraft, that took him to Vienna for that fateful meeting with Mr. Khrushchev, and afterwards to London, Paris, Berlin, and Rome in pursuit of interdependence.

AMONG THE OAKS

But on the ground, among the oaks and the dogwoods, in the hard cold light of a North American autumn, only the bright coloured cloth of ceremonial was to be seen; the Marine band in the once hated red coats, the Army special forces in green commando berets, the blues of the Navy and Air Force. As the caisson came slowly up the hill and the men of religion, or rather of the many religions that have found freedom in this land, went down to meet it, the United States Air Force bagpipe band played a lament – a Negro, wearing the kilt, at the big drum.

Earlier the members of Congress and their wives had formed a half circle below the grave, and when the foreign dignitaries arrived en masse protocol broke down. The pomp and circumstance of most of the earth were caught in a crush, and the more determined came to the fore, among them President de Gaulle and Mr. Mikoyan.

Mrs. Kennedy, supported by the Kennedy family, among them the President’s mother, took up position at the right of the grave with the late President’s personal staff in the rear.

21-GUN SALUTE

Cardinal Cushing, his gaunt voice once again a surprise as it issued from his medieval face, said the burial service, and Mrs. Kennedy and the President’s two brothers lit a flame. Then the pall bearers removed “Old Glory” from the coffin, a 21-gun salute and three musket volleys were fired. Taps (Last Post) sounded, and the final formality was over. The coffin was left on a chrome bier above the grave.

Throughout the ceremony, President Johnson, whose car on arrival was screened by trotting Secret Service agents, stood sombrely alone. All the power and the glory had descended suddenly upon him, and now this last act had been done for his predecessor, he looked lonely and shocked. The Secret Service men had their backs to him, watching the assembly, their faces impassive and some chewing gum. The realities of American life were still there.

At 8.34 p.m. G.M.T. the remains of President Kennedy were lowered into the grave. Some time in the future an appropriate tomb will be raised above it. It will not be the memorial that Mr. Kennedy would have wanted; he wanted to be a great President whose name would rank after Washington, Jefferson, and Lincoln, and much endeavour was cut short by the assassin.

SEARCH FOR PEACE

But if his work is completed by his successors, especially the search for peace abroad and the struggle for civil rights at home, history might give him that place in American history. Then this place, in view of the memorials of the great Presidents, will be splendidly appropriate. For the time being it is among a brave company.

After the ceremony at Arlington, the foreign visitors went to the White House to pay their respects to Mrs. Kennedy and, later, to the State Department, where President Johnson greeted each of them individually at a reception.

The Story of “Taps” At

President Kennedy’s Funeral

By Sergeant Jari Villanueva, United States Air Force Band

Because of the “broken” note it was assumed that SGT Clark was expressing his sorrow. The TV announcer was half truthful. The French had for many years before the funeral adopted Taps as their last call at funerals. Slurring-(which moves one note to another without a break in the air stream or re-articulating the note) that is not used in the call Taps.

Here is a brief history of what happened at the funeral:

Probably the most heard sounding of Taps occurred the afternoon of November 25, 1963 when millions around the world listened as Sergeant Keith Clark of the United States Army Band played those famous 24 notes. The occasion was the funeral of President John F. Kennedy who had been slain 3 days earlier in Dallas Texas. Sergeant Clark was a trumpet player with the Army Band (also known as “Pershing’s Own”) stationed at Fort Myer Virginia. Among his duties was to sound Taps at military funerals held at Arlington National Cemetery which is adjacent to the post. According to his recollections in William Manchester’s “The Death of a President” published by Harper and Row New York © 1967, Clark recalled that he was home going through his collection of rare books the afternoon President Kennedy was assassinated and upon hearing the news of the president’s death hurried to the nearest barber for a haircut thinking that he might be called on to sound Taps should the Chief Executive be interred at Arlington. He had played in the presence of President Kennedy earlier that month at the Tomb of the Unknowns when the president laid a wreath during Armistice Day (Veterans Day) ceremonies.

According to Manchester, it wasn’t until early Monday morning (2:30 a.m.) November 25th that it was realized that a bugler had not been requested for the funeral. Sergeant Clark was contacted immediately with information for that day. The military honors accorded would be the ones that followed military tradition. At the end of the graveside ceremony, 3 volleys were to be fired followed by the sounding of Taps, the folding of the flag, and its presentation to the widow.

At the conclusion of the ceremony Sergeant Clark played Taps and for the first time in his many daily sounding of the call, broke on the 6th note. Sergeant Clarks broken note (the 6th note) was considered the only conspicuous blunder in the otherwise ornate and grandiose ceremony of a state funeral. It was thought that it was a deliberate effect. It was not. Sergeant Clark was in place hours before the funeral procession arrived at Arlington and was placed five yards from the firing party in order to appease the television cameramen. It was cold that day and given the fact that Sergeant Clark was not given much of a chance to “warm up” it is not surprising that he missed a note. Also the fact that he was playing for a world-wide audience may have had some effect on him. After the 3 volleys were fired by a squad from the Old Guard (3rd US Infantry) Clark began Taps. As he had done daily in Arlington, he pointed the bell at Mrs. Kennedy and started the bugle call. Clark believed that the bugler should only sound Taps for the widow. On the 6th note, he cracked the note “it was like a catch in your voice, or a swiftly stifled sob” according to Manchester.

In a letter from Sergeant Clark (who retired in 1966 after 20 years service) he said “I feel the thought behind the playing and feeling used in the performance are the most important parts of each sounding of Taps”

The bugle in the photo is a Bb Signal Trumpet made by Vincent Bach for the US Army Band. It is currently in the Museum of American History in Washington DC.

Keith Clark, 74, the Arlington National Cemetery ceremonial bugler who was called on to play taps at President John F. Kennedy’s funeral after his assassination in November 1963, died of an aortic aneurysm January 13, 2002, in Fort Pierce, Florida.

Sergeant Clark, the solo trumpet player for the U.S. Army Band called “Pershing’s Own,” cracked the sixth note at the Kennedy grave site. The note was described by author William Manchester as being “like a catch in your voice, or a swiftly stifled sob” in the 1967 book “The Death of a President.”

After retiring from the Army, Clark was a music instructor at Houghton College in Houghton, N.Y. He later was a conductor and performer with southwest Florida area musical groups such as the Venice Concert Band and the Atlantic Classical Orchestra.

It is with deep sadness, that I report the passing of Keith Clark. Sergeant Clark died January 10, 2002 from complications while being operated on for a burst heart aneurysm. He was traveling to the east coast of Florida to perform at a concert when he awoke in the morning with severe abdominal pain. He was rushed to the hospital by his wife, Marge, where he died on the operating table. He was cremated and the ashes are planned to be scattered in Maine. A memorial service is scheduled for next Sunday January 20, 2002 3 PM, at First Alliance Church in Port Charlotte, Florida.

Clark was the Principal Bugler with The United States Army Band who was placed in the world spotlight when he was called to sound Taps at the Funeral of John F. Kennedy.

Keith Collar Clark was born on November 21, 1927, in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and studied trumpet with Clifford Liliya and Lloyd Geisler. After graduation from Interlochen Music School, he played with the Grand Rapids Symphony. In 1946, he enlisted in the U.S. Army and served as trumpet soloist with the United States Army Band. A deeply religious man, his life-long passion for rare books and hymns resulted in a publication, A Select Bibliography for the Study of Hymns. It was during his tenure with the Army Band that Clark received national attention as the bugler who sounded Taps for John F. Kennedy’s funeral. The Taps will be forever remembered as the Broken Taps. His bugle is on display at

Arlington National Cemetery.

After retiring from the army, Clark went on to a successful career of teaching, performing, and writing. His love of hymns brought him much recognition as a scholar and he has received numerous awards. He lived in Florida and was quite active as a trumpeter. His collection of Hymns was acquired by Regent University, Virginia Beach, VA in 1982. Mr. Clark’s great love for hymnody and Psalmody resulted in this large collection from various dealers and individuals. Containing more than 9,000 volumes, the Clark Hymnology Collection includes thousands of hymnbooks from various American denominations and churches, as well as several well-known books on hymnody from the 17th century to the present.

Keith Clark, a trumpeter, bugler, teacher, scholar, soldier, and American. He’ll be missed

Jari Villanueva

Curator, Taps/Bugle Exhibit, Arlington National Cemetery

Intruders Disturb John F. Kennedy Grave At Arlington

Saturday, December 20, 1997

One or more intruders tried unsuccessfully to dig up granite paving stones at the gravesite of President Kennedy in Arlington National Cemetery, U.S. Park Police said Saturday, December 20, 1997.

Authorities said whoever was involved in the incident Friday night or early Saturday probably gave up when they found the stones, near the eternal flame at Kennedy’s grave, weigh several hundred pounds each and are anchored together.

Police spokesman Leonard Chertoff said gaining access to the cemetery after daylight visiting hours is difficult, but he wouldn’t elaborate.

John F. Kennedy Gravesite Disturbed

December 21, 1997

President John F. Kennedy’s grave site was disturbed overnight by someone who tried, but failed, to dig up some of its granite paving stones, officials reported yesterday.

Neither the Arlington National Cemetery site’s eternal flame nor the tombstones of Kennedy, his wife, Jacqueline, and two of their children were damaged. “Someone attempted to remove stones that ring the site,” said Officer Allan Griffith of the U.S. Park Police, which is responsible for law enforcement at the cemetery. He said the culprit or culprits gave up after finding the stones were much bigger than they appeared. He said they extend several feet down, weigh about 500 pounds each and are anchored to one another. “What they had tried to do was dig down, and when they discovered how big they were, they just gave up,” he said.

The nearby grave site of Robert F. Kennedy, the former president’s slain brother, was undisturbed. The site is marked by a white-painted wooden cross.

The Kennedy Memorial Grave is the most visited at the 612-acre cemetery, across the Potomac River from Washington. The cemetery is the final resting place for more than 225,000 military heroes and other war veterans and their closest kin.

President John F. Kennedy

State Funeral

22-25 November 1963

About 1330 (eastern standard time) on 22 November 1963, President John F. Kennedy was shot by an assassin while riding in a motorcade through Dallas, Texas. The President was rushed to Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas for emergency treatment and at 1400 he was pronounced dead. An hour later President Kennedy’s body was taken to the Dallas airport for transportation back to Washington aboard Air Force One, the Presidential plane. After a wait at the field while Lyndon B. Johnson was sworn in as President aboard Air Force One, the plane departed about 1540. There was no formal departure ceremony.

When the news of President Kennedy’s death reached Washington, planning was begun immediately for a State Funeral. Frequently, officials entitled to State Funerals have been discreetly asked for their preferences in regard to the ceremonies and contingency plans have been framed accordingly, but no such information existed for President Kennedy. Responsibility for planning the funeral largely rested with Maj. Gen. Philip C. Wehle, commander of the Military District of Washington, who, under existing directives, was in charge of all State Funeral ceremonies held in Washington, D.C. General Wehle had as a basic guide the book of funeral plans and policies published in 1958, but there were to be numerous adjustments, some made with extremely brief notice, and most of them efforts to meet the wishes of the next of kin.

Upon receiving the first grim report from Dallas, Paul C. Miller, Chief of Ceremonies and Special Events for the Military District of Washington, notified the Office of the Military Aide to the President of the district’s readiness to act. Shortly afterward, he was summoned to the White House office of Ralph A. Dungan, Special Assistant to the President. Already in the office when he arrived was R. Sargent Shriver, Director of the Peace Corps and brother-in-law of President Kennedy, who was there to represent the Kennedy family. These three men began at once the difficult task of arranging funeral ceremonies under the pressure of time and without direct contact with the immediate family.

By 1600 word reached Washington that Air Force One, bearing President Kennedy’s body, was due at Andrews Air Force Base at 1800. From there, a helicopter furnished by the White House Executive Flight Detachment was to transport the body to the Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, for autopsy. As plans stood at that moment, Gawler’s morticians were then to take the body to their establishment for preparation. Afterward the President’s body was to be escorted to the White House where it was to lie until 24 November. On the 24th the body was to be taken to the Capitol to lie in state in the rotunda. At this point neither the place of burial nor the exact wishes of the next of kin regarding the funeral service were known.

At Military District of Washington headquarters, General Wehle meanwhile had opened a funeral operations center, from which all funeral details, administrative as well as ceremonial, would be controlled. As the first order of business, members of the center staff flashed alerts to military and civil units and agencies which would be or were likely to be involved in the funeral. This task included communicating with Congressional officials whose permission and support were needed in order to use the rotunda of the Capitol for the lying in state ceremony.

Between 1600 and 1800, General Wehle organized a joint service ceremony for receiving President Kennedy’s body at Andrews Air Force Base and made arrangements for its reception at the Naval Medical Center and at the White House. A Navy security guard was posted at the medical center, and a guard detail was set up to stay with the body until it was borne to the White House. An honor guard composed of members of all the armed services was to be stationed at the White House when the President’s body arrived. In preparation for the ceremony at the White House, General Wehle requested that the replica of the Lincoln catafalque, used in 1958 during the ceremonies for the Unknown Soldiers of World War II and the Korean War, be brought from storage at Arlington National Cemetery and set up in the White House. At Andrews Base Air Force troops were posted as an honor cordon, and troops from all services were to act as body bearers. Finding that more men had reported than were needed, 1st Lt. Samuel R. Bird, a 3d Infantry officer in charge of all body bearers, formed two joint service body bearer teams and placed the remaining men with the honor cordon. General Wehle had also arranged to have military police from the Military District of Washington at the airfield. Although he had been informed that the President’s body was to be taken to the medical center by helicopter, he asked that a Navy ambulance be provided at the field. (Jacqueline Kennedy, the President’s widow, later decided to use the ambulance.)

Air Force One landed at Andrews Air Force Base at 1805. Dignitaries who waited at the field included the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Chief Justice of the United States, some members of Congress, a number of diplomats, and Robert F. Kennedy, the Attorney General and brother of the slain President. As the plane came to a stop, a cargo lift carrying Lieutenant Bird and his first team of body bearers moved to the aircraft. After the hatch was opened, however, Brigadier General Godfrey T. McHugh, Air Force Aide to the President, who was on board, notified Lieutenant Bird that secret service men would carry the casket from the plane. The secret service men were obliged nevertheless to call on the trained body bearers for help in moving the casket from the lift to the ambulance.

The motorcade consisting of a police escort, General Wehle in his sedan, the ambulance, in which Mrs. Kennedy and Robert Kennedy rode, and three cars bearing members of the President’s staff departed for the Naval Medical Center. General Wehle used the helicopter that was to have carried the President’s body to send Lieutenant Bird and the second team of body bearers to the medical center so that they would be present when the ambulance arrived.

At the medical center there was some confusion when the President’s body arrived by ambulance instead of by helicopter. As instructed, Navy troops had formed a cordon from the center’s helipad to the rear (morgue) entrance to keep the way clear. But when the motorcade arrived it had no such protection and a crowd of spectators surged about it. With some difficulty, Lieutenant Bird and his body bearer team managed to reach the ambulance and carry the casket to the morgue. The team remained in the hallway as a guard.

After the autopsy the morticians from Gawler’s, for reasons of security and speed, prepared the body at the center rather than at their own facility. At this time the body was transferred to a mahogany casket which the body bearer team draped with a flag supplied by the morticians. Mrs. Kennedy and the group that had accompanied her to the medical center then came from the hospital suite where they had waited, the casket was placed in the ambulance, and the motorcade, led by General Wehle, proceeded to the White House where the President’s body would lie in the East Room.

The motorcade reached the White House at 0430 on 23 November, entering the grounds through one of the two gates on Pennsylvania Avenue. Posted at the gate to escort the ambulance to the North Portico was a detachment of twelve marines. A little more than an hour before, Mr. Shriver had asked for a small troop unit to act as escort and at 0330, a White House aide had telephoned the commanding officer of the Marine Barracks in Washington for twelve to twenty-four men in full-dress uniform. An Army bus supplied by the Military District of Washington with an Armed Forces Police escort went to the barracks and returned with twelve men of the Marine Drill Team in full dress in less than twenty minutes.

After the marines had escorted the ambulance to the North Portico entrance, the body bearer team, still led by Lieutenant Bird, carried the casket into the White House. Moving past a joint honor cordon lining the hallway, the body bearers took the casket to the East Room and placed it on the replica of the Lincoln catafalque. The first relief of an honor guard immediately took post at the four corners of the bier, facing outward. The honor guard included troops from the 3d Infantry and from the Army’s Special Forces (Green Berets). The Special Forces troops had been brought hurriedly from Fort Bragg, North Carolina, at the request of Robert Kennedy, who was aware of his brother’s particular interest in them.

Up to this point, as an inescapable result of the speed with which events had taken place and the state of shock that had overtaken a great number of the people involved, little of the existing general plan for a State Funeral had been followed. The ceremony at the White House, on the other hand, was nearly according to the plan. From the White House, invitations were sent by telegram and telephone to the official government family and the diplomatic corps to pay their respects following a private family mass in the East Room at 1030 on 23 November. From 1100 until 1900, the governmental and diplomatic officials presented themselves at the White House according to an established schedule:

1100-1400 Executive Branch – Presidential Appointees – White House Staff

1400-1430 Supreme Court

1430-1700 Senate – House of Representatives – State and Territorial Governors

1700-1900 Chiefs of Diplomatic Missions

Throughout the scheduled hours a joint service cordon positioned on North Portico Drive, at the North Portico entrance, and in the hallway guided visiting dignitaries to and through the East Room.

During the daylight hours of 23 November, gun salutes, one round each half hour, were fired at all U.S. Army installations equipped to do so, worldwide. These salutes had been ordered on the 22d by the Army Chief of Staff, who, at the same time, directed that the flags at all Army installations be flown at half-staff for thirty days.

By evening of 23 November, as direct liaison with Mrs. Kennedy and Robert Kennedy was established and their wishes were ascertained and incorporated into existing plans, arrangements for the remaining funeral ceremonies assumed definite shape. For the lying in state ceremony, the move from the White House to the Capitol was to begin at 1300 on 24 November. The route-from the North Portico entrance of the White House onto Pennsylvania Avenue, down 15th Street, again on Pennsylvania Avenue to Constitution Avenue, and then over Constitution Avenue to the Delaware Avenue entrance of the East Plaza-was to be lined by a joint service cordon. The President’s body was to be borne to the Capitol on a horse-drawn caisson. The procession, as organized at that time, was to move in the following order: police (marching); commanding general, Military District of Washington; muffed drums (no other instruments) ; detail of Navy enlisted men as honorary pallbearers; special honor guard; national color detail; clergy; caisson, flanked by four members from each of the armed services; President’s flag; body bearer detail; immediate family; President Johnson; other mourners; police (marching). Two features of the plan were distinct departures from the general concept of a State Funeral. One was the use of a caisson instead of a hearse at this point in the ceremonies; the other was the omission of a band in favor of muffled drums only. The ceremony at the Capitol itself, with one exception, was scheduled to follow the conventional plan. The exception was a series of eulogies to be delivered in the rotunda. Eulogies were by no means an innovation, but neither were they a customary part of the lying in state ceremony.

It was now firmly established that the funeral service would be held at St. Matthew’s Cathedral in Washington and that burial would take place in Arlington National Cemetery. The composition and order of the main funeral procession had yet to be fully determined. In particular, provisions had to be made for the diplomatic corps and other representatives of foreign nations. But it was decided that in the move from the Capitol to St. Matthew’s Cathedral the procession would halt at the White House. There, members of the Kennedy family were to leave the cars in which they had ridden from the Capitol and, joined by President Johnson and other dignitaries, were to proceed on foot to the cathedral.

On 22 November, in anticipation of a decision that President Kennedy would be buried in Arlington National Cemetery, John C. Metzler, the cemetery superintendent, selected three possible gravesites. One was at Dewey Circle in the southeastern corner of the cemetery; the second was near the grave of John Foster Dulles, southwest of the Memorial Amphitheater; and the third was on the slope east of the Custis-Lee Mansion. About noon on 23 November, Robert Kennedy and other members of the family, accompanied by Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara, toured these sites with Mr. Metzler. They made no decision but appeared to favor the site near the mansion. At midafternoon the same day, the group returned with Mrs. Kennedy and at this time the mansion site was chosen. Over the next two days the work of surveying, marking, and otherwise preparing the gravesite continued almost to the hour of the burial service.

In preparation for the procession from the White House to the Capitol on 24 November, the joint service honor cordon lined both sides of the route of march by 1230. The Army, Marine Corps, Navy, and Air Force each furnished 240 officers and men for the cordon. The men were spaced twenty-five feet apart and faced toward the street.

The procession formed on the North Portico Drive, which also was lined by an honor cordon. (Diagram 54) About 1300, the body bearers carried President Kennedy’s casket from the East Room, passed through an honor cordon posted in the hallway and on the portico itself, and placed the casket on the caisson. No music was played during the departure ceremony, nor would there be any during the march-only the beat of the muffled drums.

Metropolitan Police on foot headed the procession, followed by General Wehle and a joint service drum detail with four snare drummers from each service, one bass drummer each from the Army and Marine Corps, and a drum major and leader from the Army. After the drummers came a Navy escort company of four officers, three petty officers, and eighty-six enlisted men. Next came a special honor guard composed of the joint Chiefs of Staff and led by General Maxwell D. Taylor. The White House military aides, Major General Chester V. Clifton of the Army, Captain Tazewell Shepard of the Navy, and Brigadier General Godfrey T. McHugh of the Air Force, followed them. Behind these officers was the national color detail, two men from the Army and one each from the Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, and Coast Guard. Three members of the clergy were next in the procession the Very Reverend Francis B. Sayre, Jr., dean of Washington National Cathedral; the Right Reverend John S. Spencer of Sacred Heart Shrine; and the Very Reverend K. V. Kazanjian, rector of St. Mary’s Armenian Apostolic Church. After the clergy came the caisson, drawn by matched grays. Twenty servicemen flanked the caisson, ten on a side. Each group of ten included two men from each of the services, these ordered front to rear according to the seniority of the service: Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, and Coast Guard. Behind the caisson President Kennedy’s personal flag was carried by Seaman E. Nemuth of the Navy, who was followed by the body bearer team under Lieutenant Bird and Pfc. Arthur A. Carlson of the 3d Infantry, leading the caparisoned horse, Black Jack.

A column of ten automobiles followed: The first carried Mrs. Kennedy, her two children, John and Caroline, Robert F. Kennedy, and President and Mrs. Johnson; the second, two of President Kennedy’s sisters and their husbands; the third, the widow’s stepfather and mother, Mr. and Mrs. Hugh D. Auchincloss, and others of the Auchincloss family; the fourth, Mrs. Robert F. Kennedy, several of her children, and Sargent Shriver. (Mrs. Shriver, another of President Kennedy’s sisters, Rose Kennedy, the President’s mother, and Edward M. Kennedy, the President’s younger brother, were en route from Hyannisport, Massachusetts, at this time.) In the remaining automobiles were a number of employees of the Kennedy family and of the White House, and security officials.

At the press corps’ own request, a large delegation of the press followed the cars in the procession on foot. Bringing up the rear was another detail of Metropolitan Police on foot. During the march, many in the large crowd of spectators evidently interpreted the presence of the press corps group as an invitation for the public to join the procession. At first police and troops blocked off the marching spectators, but as the procession drew nearer the Capitol they allowed the people to fall in behind the police.

In preparation for the ceremony at the Capitol, government and diplomatic corps officials meanwhile had been ushered to designated positions in the rotunda. Outside, an honor cordon of seventy Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, and Coast Guard members lined the east steps. Thirty of President Kennedy’s aides and advisers stood aligned at the top of the steps. On the plaza, the US Air Force Band formed at the south side of the steps.

The procession from the White House arrived at the Capitol about 1350 where part of it halted at the east steps. The drummers, the Navy escort company, and the joint group of twenty servicemen that had flanked the caisson continued marching and left the ceremonial area. After those who had ridden in automobiles had dismounted, the chauffeurs drove the cars to a holding area on the south side of the plaza. The members of the procession meanwhile were guided to positions for the procession into the rotunda.

After the participants were in place, and on signal from the site control officer, the joint honor cordon presented arms. The Air Force Band then sounded four ruffles and flourishes and played “Hail to the Chief.” Ordinarily this music is played at 120 beats to the minute; but at Mrs. Kennedy’s request, it was played dirge adagio, or at 86 beats to the minute. The band then began the Navy hymn “Eternal Father, Strong to Save.” The saluting battery from the 3d Infantry had been posted near the Senate garage at Louisiana Avenue and D Street. At the first note of the Navy hymn, the battery began a 21-gun salute, spacing the rounds five seconds apart. At the same time, the body bearers removed the casket from the caisson.

The escort commander, General Wehle, led the way up the steps. Behind him came the special honor guard, the national color detail, the clergy, the casket, the personal flag, and the Kennedy family and other mourners. After the procession entered the rotunda, the band ceased playing the hymn and the honor cordon ordered arms.

Upon entering the rotunda, the special honor guard turned left and stopped at a position near the east entrance. The national color detail, the clergy, the body bearers and casket, and the personal flag bearer turned right, moved in a semicircle, then turned back toward the east entrance to reach the Lincoln catafalque in the center of the hall. The family party also turned right after entering and stopped at a position near the east entrance.

After placing the casket on the catafalque, the body bearers stood fast while the colors were posted. (Because the base for the President’s flag was inadequate, the flag bearer had to hold the flag in place throughout the ceremony.) The commander and first relief of the guard of honor came in next through the west entrance; the commander immediately dismissed the body bearers and posted his first relief at the bier. The full guard was a joint group of five officers and thirty-two men representing all five uniformed services.

Following the posting of the guard, Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield, Chief Justice Earl Warren, and Speaker of the House John W. McCormack, in that order, delivered short eulogies. When the speakers had finished, Mrs. Kennedy went forward, knelt briefly at the bier, and left the rotunda with Robert Kennedy by the east entrance. The other mourners then left and after the rotunda was clear it was opened to the public. People began filing by the bier at 1400; a great number were still waiting to enter when the rotunda was closed to the public at 0930 on 25 November.

After the ceremony at the Capitol, final plans for the remaining ceremonies were completed during meetings held at the White House, Arlington National Cemetery, and Headquarters, Military District of Washington. The composition and movement of the main funeral procession were two of the first matters settled. In the process several changes were made to a preliminary organization of the military escort as a result of requests by the President’s widow. Whereas the preliminary plan called for the Army Band to lead the first march unit of the escort, Mrs. Kennedy asked that the Marine Band be used. The Army Band subsequently was scheduled to participate in the arrival ceremony at St. Matthew’s Cathedral. Mrs. Kennedy also wanted a company of marines that had been earmarked to move in the first march unit to be relocated at the rear of the escort, hence close to the caisson, and requested that a platoon of Army Special Forces troops be added to the procession and positioned just ahead of the Marine company.

The route of the funeral procession from the Capitol to St. Matthew’s Cathedral lay over Constitution Avenue, Pennsylvania Avenue, 15th Street, and again over Pennsylvania Avenue to the White House, then over 17th Street, Connecticut Avenue, and Rhode Island Avenue to the cathedral.

ORDER OF MARCH, PROCESSION FROM THE US CAPITOL

TO THE WHITE HOUSE, CEREMONY FOR PRESIDENT JOHN F. KENNEDY

Police escort

Escort commander

Commander of troops

First march unit

US Marine Band (91)

Company, cadets, US Military Academy (89)

Company, midshipmen, US Naval Academy (89)

Company, cadets, US Air Force Academy (89)

Company, cadets, US Coast Guard Academy (89)

Company, US Army (89)

Company, US Navy (89)

Squadron, US Air Force (89)

Company, US Coast Guard (89)

Company, servicewomen, composite (82)

Second march unit

US Navy Band (91)

Company, Army National Guard (89)

Company, Army Reserve (89)

Company, Marine Corps Reserve (89)

Company, Navy Reserve (89)

Squadron, Air National Guard (89)

Squadron, Air Force Reserve (89)

Company, Coast Guard Reserve (89)

Third march unit

US Air Force Band (91)

Representatives, 22 national veterans’ organizations

Platoon, Special Forces, US Army (38)

Company, US Marine Corps (89)

Cortege

Special honor guard

National color detail

Clergy

Caisson and body bearers

Personal flag bearers

Caparisoned horse

Kennedy family

Police escort

The special honor guard, the clergy, and the Kennedy family were to ride in automobiles as far as the White House, then, except for the President’s two children who would remain in an automobile, were to continue to the cathedral on foot. Other persons scheduled to join the cortege at the White House also were to proceed on foot. These included President and Mrs. Johnson, cabinet members and military service secretaries, members of Congress, justices of the Supreme Court, members of the White House staff, personal friends, members of the diplomatic corps, and a large assemblage of foreign dignitaries.

The Department of State, which was responsible for arranging the presence of representatives of foreign governments, at first had decided not to invite foreign dignitaries to attend or participate in the ceremonies. The department reasoned that since there was very little time to send out invitations before the funeral, some invitations might reach their destinations late and cause deep embarrassment. The department maintained this position until the morning of 23 November. By then, however, certain foreign dignitaries had announced their intention of attending the ceremonies as private persons, among them President Eamon de Valera of Ireland, Chancellor Ludwig Erhard of West Germany, and Prime Minister Sir Alec Douglas-Home of England. Around midday on the 23d, after word was received that General Charles de Gaulle, President of France, and King Baudouin I of Belgium planned to attend, the Department of State hastily cabled formal invitations. A flood of acceptances followed. In all, ninety-two representatives of foreign governments accepted, including eight heads of state and ten prime ministers.

After the final plans were drafted on 24 November, only one more change was made in the composition of the procession to St. Matthew’s Cathedral: a small contingent of bagpipers, the Black Watch of the Royal Highland Regiment, was to join the procession at the White House. This unprecedented participation of a foreign unit in the funeral for a President of the United States was the result of another of Mrs. Kennedy’s requests. The pipers were to fall in behind the Marine company at the rear of the military escort. The procession would be further lengthened when the persons assembled at the White House joined the march. The full cortege would then observe the following order of march from the White House to St. Matthew’s Cathedral:

Special honor guard

National color detail

Clergy

Caisson

Personal flag bearer

Caparisoned horse

Kennedy family

President and Mrs. Johnson Kennedy children (in limousine)

Foreign delegations

Supreme Court justices

Cabinet members

Members of the Congress

Presidential assistants

Personal friends

White House staff

The organization of the procession would undergo other changes for the movement from St. Matthew’s Cathedral to Arlington National Cemetery. The Black Watch pipers were to leave the military escort at the cathedral, as were the representatives of veterans’ organizations moving with the escort’s third march unit. Originally, these representatives were scheduled to attend the funeral service, but a lack of sufficient seating space in the cathedral forced a cancellation of this plan. As an alternative, they were allotted space at the graveside rites, and transportation was provided them from the cathedral to the cemetery. A motorcade of 107 vehicles also was organized for the movement of the cortege to the cemetery. To join the cortege at the cathedral were former Presidents Truman and Eisenhower and state and territorial governors, all of whom were invited to attend the funeral service.

Beyond plans for the composition and movement of the funeral procession on 24 November, other arrangements were made to carry out further wishes of Mrs. Kennedy: the US Naval Academy Choir was scheduled to perform two selections at the White House during the time the funeral procession was halted there while en route from the Capitol to the cathedral; the 3d Infantry’s Colonial Fife and Drum Corps, which Mrs. Kennedy wanted somewhere along the procession’s route of march to the cemetery, was assigned a position on the green at the Memorial Gate entrance to the cemetery, although it was not scheduled to play.

In a wide departure from customary graveside procedure in which a band, standing fast in formation, plays an appropriate hymn as the casket is carried from the caisson to the grave, Mrs. Kennedy preferred that the Air Force Bagpipe Band march past the gravesite playing “Mist Covered Mountain” while the movement of the casket was taking place. The Air Force group was so scheduled, and a route permitting the group to perform as requested was marked out at the gravesite.

Out of awareness of President Kennedy’s admiration of a silent drill he had seen performed by Irish Guards (military cadets) while visiting Ireland, Mrs. Kennedy also asked that this group perform the same drill during the graveside rites. Accordingly, after arranging to have the Irish Guards present, it was scheduled that they would perform their drill at the foot of the grave and then join the military escort at its more distant graveside position.

Of two further requests made by Mrs. Kennedy, both of which concerned the graveside ceremony, one was that the only flowers at the grave itself be a basket of blossoms taken from the White House garden. All other floral pieces were to be banked on the hillside above the grave and were to be arranged by the White House gardener.

The last request was difficult to meet. About 1500 on 24 November, the superintendent of Arlington National Cemetery, John Metzler, received word from the White House through the Military District of Washington funeral operations center that Mrs. Kennedy wished to have constructed at the gravesite an “eternal flame” which she would light during the burial service. Mr. Metzler turned to the post engineer at Fort Myer, Lieutenant Colonel Bernard G. Carrol, for help. Using commercial components Colonel Carrol, assisted by several other engineers and specialists, constructed and installed the mechanism by midnight. From wire, they made a frame shaped like half a ball, three feet in diameter at the base and eighteen inches high, which was later covered with evergreen boughs. This frame supported a Hawaiian torch. Over three hundred feet of copper tubing ran from the torch to a tank of propane gas. (Later a permanent gas line was installed.)

On the evening of 24 November, General Wehle’s headquarters published and distributed the final plans for the remaining ceremonies. General Wehle then instructed representatives of all government agencies and the commanders of all military units scheduled to participate. The meeting lasted until 0200 on 25 November.

Ceremonies were to begin at the Capitol at 1030 on the 25th. Before that hour, 1,200 troops cordoned the route of the funeral procession from the Capitol to the cathedral. The Army, Marine Corps, Navy, and Air Force each supplied three hundred men for the street cordon and provided an additional forty-four men each to cordon the longer route from the cathedral to the cemetery. The plan called for the necessary repositioning and adding of troops to be accomplished while the funeral service was in progress.

At the Capitol, a joint honor cordon lined the east steps for the ceremony of carrying President Kennedy’s body from the rotunda. Inside the rotunda waited the clergy, body bearers, and color bearers. On the plaza, the caisson was in a central position at the foot of the steps. To the immediate south was the US Coast Guard Band. To the north were the special honor guard (the joint Chiefs of Staff and the military aides to the President) and the escort commander, General Wehle. The escort units were along Constitution Avenue, from 3d Street eastward, aligned for the procession.

Mrs. Kennedy and other members of the Kennedy family in five cars arrived at the Capitol from the White House at 1038. Mrs. Kennedy, accompanied by her husband’s two brothers, Robert and Edward, entered the rotunda for a final visit, then returned to the plaza and joined other family members near the band.

Inside the rotunda the guard of honor was dismissed after the Kennedy visit. The body bearers secured the casket and, preceded by the national color detail and the clergy and followed by the personal flag bearer, carried it from the hall. (Diagram 59) The formation halted at the top of the east steps. The honor cordon presented arms while the band sounded ruffles and flourishes, played “Hail to the Chief,” and then began the hymn “O God of Loveliness.” On the hymn’s first note, the procession moved down the steps to the caisson. After the body bearers secured the casket on the caisson the band stopped playing and those who were to move with the procession went to their assigned positions for the march. The body bearers did not join the cortege but were sent by bus to the cathedral to be on hand when the procession arrived.

When the funeral procession reached the White House, all escort units save the company of marines at the very rear moved past it, turned right off Pennsylvania Avenue onto 17th Street, and halted after the last unit had made the turn. In accord with another of Mrs. Kennedy’s wishes the left platoon of the Marine company, as it reached the White House, turned in the northeast gate and led the cortege onto North Portico Drive. As the cortege moved around the drive, the US Naval Academy Choir on the White House lawn sang “Londonderry Air” and “Eternal Father, Strong to Save.” The remainder of the Marine company meanwhile continued on Pennsylvania Avenue, then halted at the northwest gate just in front of its left platoon now halted on the drive. At this point the Black Watch pipers, who had waited near the northwest gate, took position immediately behind the Marine platoon.

The halt at the White House lasted only a few minutes. The members of the Kennedy family left the vehicles that had brought them from the Capitol and took their places behind the caisson, the Presidential flag, and the caparisoned horse. President and Mrs. Johnson took positions behind the Kennedy family, but ahead of a limousine bearing Caroline and John Kennedy; the other dignitaries who had assembled at the White House fell in behind in the scheduled order. The Black Watch pipers played “The Brown Haired Maiden” as the cortege then moved to rejoin the procession. When it reached the military escort on 17th Street, the full procession resumed the march to the cathedral.

The escort units turned off Connecticut Avenue onto Rhode Island Avenue to reach St. Matthew’s, marched past the cathedral, made three left turns to circle the irregular block, and halted on Connecticut Avenue facing south. The Black Watch group and the representatives of veterans’ organizations then left the formation, the latter proceeding to Arlington National Cemetery to attend the graveside rites. The remainder of the escort stood fast, awaiting the conclusion of the funeral service.

As the cortege reached the cathedral, the caisson was stopped at the entrance. A joint honor cordon of one officer and twenty-five men lined the steps, and the US Army Band was in formation at the base and to the right side of the steps. After the caisson came to a stop, Mrs. Kennedy, without pause, led the marchers through the honor cordon into the cathedral. Other family members, family friends, and invited dignitaries, none of whom had marched in the procession, already were seated. Among them were Mrs. Rose Kennedy, the state and territorial governors, and former Presidents Truman and Eisenhower.

After the President’s widow and the other mourners had been seated, and after the special honor guard had formed at the base of the cathedral steps opposite the Army Band, the body bearers moved to a position behind the caisson. The cordon troops then presented arms and the band played ruffles and flourishes, “Hail to the Chief,” and the hymn “Prayer for the Dead.” On the hymn’s first note, the body bearers took the casket from the caisson. General Wehle then led the way up the cathedral steps, followed by the national color detail, clergy, casket, personal flag, and special honor guard.

When the body bearers had carried the casket part of the way up the steps Cardinal Richard J. Cushing, who would celebrate the pontifical requiem mass for President Kennedy, appeared before them to bless the casket, a normal part of the mass. The body bearers were obliged to halt in an awkward position on the steps, with the weight of the casket distributed unevenly, and were able to maintain their position only with difficulty. After the blessing, the procession continued into the cathedral where the casket was placed on a movable bier and wheeled to the front of the room. Cardinal Cushing then conducted the requiem mass.

At the end of the service, the body bearers moved the casket up the center aisle of the cathedral to join the national color detail at the main door. The joint honor cordon on the steps outside presented arms, and the Army Band played ruffles and flourishes, “Hail to’ the Chief,” and the hymn “Holy God, We Praise Thy Name.” As the hymn was begun, the body bearers carried the casket through the joint honor cordon and placed it on the caisson. The family and others observed this ceremony from the cathedral entrance. Once the casket was on the caisson the honor cordon ordered arms and the family and guests were escorted to their cars for the procession to Arlington National Cemetery.

The departure from the cathedral was somewhat confused. Because of the mistaken, if well intended, intervention of a Presidential aide, few of the cars were in the proper order; and because the cathedral stood within a limited street network, there was little that could be done to correct the situation without undue delay. Thus, with many of the cars still out of prescribed order, the cortege proceeded by way of Connecticut Avenue, 17th Street, Constitution Avenue, and Henry Bacon Drive, then counterclockwise around the Lincoln Memorial, across Memorial Bridge, and over Memorial Drive to the cemetery Memorial Gate. Just short of the gate, the greater part of the military escort, which was not scheduled to participate in the graveside rites, turned left on Arlington Ridge Road and proceeded to dismissal points along that road where they were picked up by buses. Of the escort units, the Marine Band and one platoon each of the Regular Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, and Coast Guard entered the cemetery.

As these units led the procession into the cemetery, moving by the Colonial Fife and Drum Corps which had formed on the lawn at Memorial Gate, the cemetery superintendent met the column and guided it to the gravesite. The procession moved via Schley, Sherman, and Sheridan Drives. The route was roped off and cordoned by troops from the 3d Infantry, who presented arms in ripples as the procession passed. Upon reaching the gravesite, the Marine Band and five platoons of escort troops immediately moved to their graveside positions. Already in position was a group of Army Special Forces troops lining both sides of a cocomat that ran from Sheridan Drive to the grave, and at the foot of the grave stood the thirty members of the Irish Guard. Also in place to perform, as Mrs. Kennedy had requested, was the Air Force Bagpipe Band. In addition, an Army bugler, a 3d Infantry firing party, and the 3d Infantry saluting battery were in their positions, ready to participate in the final rites.

The caisson was halted at the cocomat runner. The automobiles bearing the Kennedy family, President Johnson and his party, and the foreign dignitaries parked farther to the rear along Sheridan Drive. The foreign officials dismounted and moved to the graveside. Under the guidance of Superintendent Metzler, the Kennedy family and President Johnson and his party remained for the time being in their automobiles in order that their arrival at the grave would coincide with a flyover by Air Force and Navy jet fighters and by the Presidential plane, Air Force One. After about four minutes, the cemetery superintendent assisted the members of the Kennedy family from their cars and signaled secret service men to help President Johnson and his party.

The Marine Band opened the graveside rites with ruffles and flourishes and played the national anthem. When the anthem ended, the Air Force pipers began a slow march past the gravesite as they played “Mist Covered Mountain.” At the same time the body bearers removed the casket from the caisson. With General Wehle leading, the national color detail, clergy, casket, personal flag, and special honor guard following, the procession moved through the cordon of Army Special Forces troops to the grave. The cemetery superintendent followed, escorting the Kennedy family.

When they reached the grave, the body bearers backed the casket onto the placer, since the hurriedly constructed torch at the head of the grave prevented use of the conventional method. At this moment, while the superintendent was showing members of the family to their graveside positions, the flyover took place. Fifty fighter aircraft, thirty- Air Force F-105’s and twenty Navy F-4B’s, passed overhead in three V formations, one plane missing from the last V in tribute to the fallen leader. Following the fighters came Air Force One, piloted by Col. James B. Swindal. After the tribute from the air the Irish Guards executed their silent drill; at its conclusion they left the graveside and stood with the escort units.

Cardinal Cushing then conducted the service. When he had finished, the escort troops saluted while the 3d Infantry battery fired twenty-one guns. Cardinal Cushing pronounced the benediction. The troops again saluted while the 3d Infantry firing party delivered three volleys. The bugler sounded taps.

The US Marine Band began to play the hymn “Eternal Father, Strong to Save,” and at the same time the body bearers folded the flag and handed it to Mr. Metzler. Then, as the hymn was concluded, Cardinal Cushing stepped forward and blessed the eternal flame. Mr. Metzler presented the folded flag to Mrs. Kennedy. Maj. Stanley P. Converse, executive officer of the 1st Battalion, 3d Infantry, then lighted a taper and handed it to Mrs. Kennedy, who lighted the torch that would become the eternal flame, thus ending the ceremonies for her husband. Army Special Forces troops, although they were not scheduled to do so, posted themselves at the four corners of the grave.

Old Guard Veterans Remember JFK Funeral

Kennedy Family At Arlington National Cemetery: 22 November 2000

An Eternal Flame For A President

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard