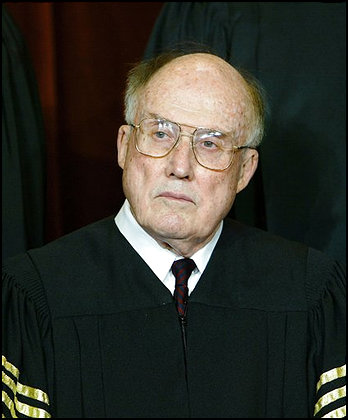

The Honorable William Hubbs Rehnquist

On Saturday, September 3, 2005, The Honorable William Hubbs Rehnquist, Chief Justice of the United States.

Beloved husband of the late Natalie Cornell Rehnquist; devoted father of James C. Rehnquist of Sharon, Massachusetts, Janet Rehnquist of Arlington, Virginia and Nancy Spears of Middlebury, Vermont; loving brother of Jean Laurin of Grand Rapids, Michigan. He is also survived by nine grandchildren.

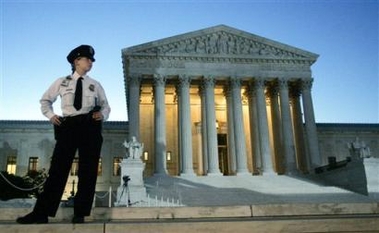

Chief Justice William Rehnquist will lie in repose in the Great Hall of the United States Supreme Court on Tuesday from 10:30 a.m. to 10 p.m. and on Wednesday from 10 a.m. to 12 Noon.

Private services will be held at St. Matthew’s Cathedral, 1725 Rhode Island Avenue, N.W., Washington, DC 20036. Interment to follow.

In lieu of flowers, memorial contributions may be made in his name to the Greensboro Free Library, General Delivery, Greensboro, Vermont 05841 or the Lutheran Church of the Redeemer, 1545 Chain Bridge Rd., McLean, Virginia 22101.

Rehnquist to be buried at Arlington Cemetery

Chief justice’s body will lie in repose at Supreme Court through Wednesday

Chief Justice William Rehnquist’s body will lie in repose in the Great Hall of the Supreme Court on Tuesday and Wednesday and he will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery following funeral services.

The court announced Sunday that the public will be invited to pay its respects from 10:30 a.m. EDT until 10 p.m. Tuesday and from 10 a.m. until noon Wednesday.

Funeral services will be at 2 p.m. at St. Matthew’s Cathedral in Washington, with funeral services open to friends and family. The burial at Arlington will be private.

In a sensitive ritual, Supreme Court officials and the Military District of Washington coordinated the funeral arrangements with Rehnquist’s family.

Timing and other details were in the hands of the family, said Barbara Owens, a spokeswoman for the Army’s Joint Force Headquarters National Capitol Region/Military District of Washington.

Rehnquist died Saturday at the age of 80, and the Supreme Court announced the arrangements Sunday evening.

September 4, 2005

William H. Rehnquist, Architect of Conservative Court, Is Dead at 80

William H. Rehnquist, who died Saturday at the age of 80 almost a year after learning he had thyroid cancer, helped lead a conservative revolution on the Supreme Court during 19 years as chief justice of the United States.

Chief Justice’s Rehnquist’s death came six weeks after he refuted rumors that he would soon retire by announcing that he intended to serve as long as his health permitted. At the time of that announcement, on July 14, photographers had been camped out for weeks outside his house in Arlington, Va.

Following his diagnoses of cancer last October, the chief justice was treated with chemotherapy and radiation and missed months of the court’s arguments. But he returned to the bench in March and participated actively in the court’s business, despite breathing and speaking through a hole that surgeons had cut in his throat.

Instead of the chief justice, it was Justice Sandra Day O’Connor who announced her retirement at the end of the court’s last term. President Bush named a former Rehnquist law clerk, Judge John G. Roberts Jr. of the federal appeals court here to succeed her, and confirmation hearings were set to begin on Tuesday.

Including 14 years as an associate justice, Chief Justice Rehnquist’s tenure on the court was not only one of the longest in the institution’s history but also one of the most consequential. With a steady hand, a focus and commitment that never wavered, and the muscular use of the power of judicial review, he managed to translate many of his long-held views into binding national precedent.

Chief among those was an enhanced role for the states within the federal system, which the court accomplished under his leadership by overturning dozens of federal laws that sought to project federal authority into what the Supreme Court majority viewed as the domain of the states.

In the zero-sum game of the tripartite separation of powers, the Supreme Court’s own power grew correspondingly as the justices circumscribed the power of Congress. The court’s institutional enhancement was an irony of Chief Justice Rehnquist’s tenure, because another goal that he accomplished in large measure was to shrink the role of the federal courts by taking them out of the business of running prisons, school systems and other institutions of government.

The Rehnquist years included one historic episode of galvanizing drama and deep divisiveness, the decision in Bush v. Gore that decided the 2000 presidential election by ending the recount in Florida and handing a wafer-thin victory to George W. Bush. While Chief Justice Rehnquist voted with the 5 to 4 majority, his central role in the case was largely behind the scenes and the controlling opinion did not carry his name.

While Chief Justice Rehnquist was a self-confident and not unduly modest man, that near-invisibility was itself quite characteristic and led many people to assume incorrectly that one of his flashier colleagues, Justice Antonin Scalia, had played the stage-manager’s role in the events that resulted in the final decision in Bush v. Gore.

“Rehnquist is the opposite of Scalia,” Professor Robert C. Post of the Yale Law School said in an interview. “Rehnquist doesn’t particularly want to be noticed. He’s not interested in getting credit. He’s just interested in getting the job done.”

Chief Justice Rehnquist also had the unusual experience of presiding over a presidential impeachment trial, a role ordained for the chief justice by the Constitution. During the five weeks in early 1999 that it took the Senate to try and acquit President Bill Clinton on charges of perjury and obstruction of justice, the chief justice was an unfamiliar presence in the Senate chamber, occasionally moving the proceedings along but having little of substance to do. “I did nothing in particular and I did it very well,” he told a television interviewer, Charlie Rose, two years later, borrowing a line from one of his favorite Gilbert and Sullivan operettas, “Iolanthe.”

“Iolanthe” also inspired Chief Justice Rehnquist to modify his basic black judicial robe by adding four gold stripes to each sleeve, copying the costume worn by the Lord Chancellor in a local production of the operetta. Since the chief justice had never paid any noticeable attention to his attire, the new adornment was startling. Where some saw self-aggrandizement, others saw the sartorial manifestation of a wry sense of humor.

Chief Justice Rehnquist was an efficient administrator who had the affection and respect of even those colleagues who disagreed with him most vigorously. On Jan. 7, 2002, the 30th anniversary of his swearing-in as a justice, Justice John Paul Stevens, the senior associate justice and a liberal who was the furthest removed from the chief justice ideologically, read a statement from the bench congratulating him for reaching the milestone.

“On behalf of all your colleagues,” Justice Stevens said, “I want to express our sincere appreciation for the exemplary way in which you have performed the special responsibilities of your high office, with particular emphasis on the efficiency, good humor, and absolute impartiality that you have consistently displayed when presiding at our conferences.”

Chief Justice Rehnquist was a lucky man, in that the turn of the political wheel sent new justices to the court and provided him with sufficient allies – if barely so – for his most cherished causes. His unusually long tenure also provided the gift of time.

But his ultimate success was also a testament to his own tenacity and skill. He combined an unfaltering sense of mission with high intelligence, patience, the strategic prowess of a serious poker player, which he was, and the attention to detail of an art-lover and serious amateur painter, which he also was. He had held many of his views since early adulthood, and he took the long view: with seeming nonchalance, he would plant a phrase in an opinion in the expectation that it would take root, blossom, and prove even more useful in some future case. Time proved him right, not always, but often enough.

A Nixon Appointee

William H. Rehnquist was 47 years old and far to the right of the judicial mainstream when President Richard M. Nixon named him to the Supreme Court as an associate justice in 1971. A Goldwater Republican, he was then an assistant attorney general in the Nixon Justice Department. He was a polarizing figure, the symbol of the president’s determination to dismantle the liberal legacy of the Warren Court.

Two and a half years into the chief justiceship of Warren E. Burger, that goal appeared far distant, given the continued service of such liberal titans as Justices William O. Douglas, William J. Brennan Jr., and Thurgood Marshall. In his first decade on the court, until he gained allies through the three appointments made by President Ronald Reagan, Justice Rehnquist was frequently a lone dissenter, his language pithy but his arguments seemingly futile.

“The existence of the death penalty in this country is virtually an illusion,” he declared in one typical dissent in 1981, complaining that “virtually nothing happens except endlessly drawn out legal proceedings.” No other member of the court joined him.

But eventually not only a majority of the court but Congress as well – due in part to Chief Justice Rehnquist’s advocacy from his platform as head of the Judicial Conference of the United States, the judiciary’s policy-making arm – agreed that there were too many procedural obstacles blocking states from carrying out the death penalty. Through the interaction of legislation and Supreme Court decisions, the pace of executions quickened sharply through the 1990’s.

In general, there was little in those early years to indicate the success that lay ahead. Named by President Ronald Reagan in 1986 as the 16th chief justice of the United States, succeeding Warren Burger, he eventually presided over a working, if narrow, conservative majority that turned his one-time dissents into majority opinions and gave him the power to shape the law according to views he had held as a young lawyer and even as a student before that.

When he took his seat as an associate justice on Jan. 7, 1972, the dominant theme in discussions about the Supreme Court was law and order. President Nixon was a harsh critic of the criminal procedure decisions of the Warren Court and correctly discerned that he would have an ally in Assistant Attorney General Rehnquist. During the Rehnquist years, the court enhanced the ability of the police to conduct searches and to have the results of the search introduced at trial; expanded police officers’ immunity from suit for constitutional violations; and cut back sharply on the role of the federal courts in reviewing state-court criminal convictions.

Chief Justice Rehnquist defied the expectations of many, however, in voting in June, 2000, to reaffirm one of the Warren Court’s most famous and disputed rulings, Miranda v. Arizona, which required the police, as a protection against coerced confessions, to advise suspects of their right to counsel and to remain silent.

Chief Justice Rehnquist lost some battles, as well, on a court that remained closely divided on most fundamental issues. One of the only two dissenters, with Justice Byron R. White, from the 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade that recognized a constitutional right to abortion, he fell short by one vote in Planned Parenthood v. Casey in 1992 of seeing that decision overruled.

And in a 1989 case, Texas v. Johnson, that found flag-burning to be a form of political expression protected by the First Amendment, he was reduced to the role of impassioned dissenter. Quoting the famous lines, “Shoot if you must, this old grey head, but spare your country’s flag,” from the Civil War poem, “Barbara Frietchie,” he said the flag was “the visible symbol embodying our Nation” and “not simply another ‘idea’ or ‘point of view’ competing in the marketplace of ideas.”

He remained a lightning rod whose influence was deplored by liberal academics and commentators. In a 2003 critique of the Rehnquist Court, “Overruling Democracy” (Routledge), Professor Jamin B. Raskin of the American University Law School wrote that Chief Justice Rehnquist’s legacy was “a thick jurisprudence hostile to popular democracy and protective of race privilege and corporate power.” But his tenure had many admirers. Kenneth W. Starr, the former solicitor general, praised the Rehnquist years in his book on the court, “First Among Equals” (Warner Books, 2002) for returning to “lawyerly rigor” and rejecting the “policy-making” tendencies of the court under Chief Justices Earl Warren and Warren E. Burger.

Through it all, through two testy confirmation hearings and decades as the highly visible embodiment of the court’s counterrevolution, William Rehnquist remained a nearly imperturbable figure who strolled the court’s grounds, unrecognized, in a jaunty straw boater and padded its halls in rubber-soled Hush Puppies, size 14D.

At six feet three inches, and often stooped due to back pain, he was rather ungainly. A flat Midwestern accent revealed his Wisconsin childhood, although he left the Midwest for military service in World War II at the age of 19 and never returned there to live. His adopted home state was Arizona.

He loved amateur theatricals, led his law clerks in sing-alongs, and would bet with his fellow justices over anything, including the depth of snow on the marble plaza outside the court. He answered a contest in The Washington Post, which asked readers to figure out what make of car was referred to by the license place 1 DIV 0. “I believe it refers to an Infiniti, since when you divide 0 into 1, the result is infinity,” he wrote in his winning answer.

Judge, and Author

He wrote books on Supreme Court history as well as an unpublished murder mystery set in the Justice Department. Asked by Brian Lamb of C-Span, in a 1998 interview, why he liked to write books, he replied: “It’s very nice to be able to write something you don’t have to get four other people to agree with before it can become authoritative.”

One of the most notable aspects of Chief Justice Rehnquist’s career was his consistency. Five years into his tenure on the Court, the Harvard Law Review published a “preliminary” appraisal by Professor David L. Shapiro. Professor Shapiro identified three basic elements of the Rehnquist judicial philosophy: conflicts between the individual and the government should be resolved against the individual; conflicts between state and federal authority should be resolved in favor of the states; and questions of the exercise of federal jurisdiction should be resolved against such exercise. The 1976 article was often cited in later years because it proved to be such a reliable roadmap to the Rehnquist judicial philosophy.

Chief Justice Rehnquist, who had masters degrees in political science from both Stanford and Harvard Universities, defined himself in political science terms as a pluralist, one who believed there should be numerous sources of power within the government. “I’m a strong believer in pluralism,” he told an interviewer in 1985. “Don’t concentrate all the power in one place.”

This outlook translated into a limited view of the role of the federal courts, because the courts were simply one institution among others, with no claim to greater wisdom or moral authority. This view was in sharp contrast to the judicial liberalism that was dominant when Chief Justice Rehnquist came of age as a young lawyer, when the federal courts were thought to have – or behaved as if they had – an almost oracular ability to discern the hidden meaning of the Constitution in light of the public good.

His belief in a limited judicial role was further bolstered by a long-held skepticism about whether any theory of the common good was inherently preferable to any other. In a 1976 article, “The Notion of a Living Constitution,” published in the University of Texas Law Review, he wrote: “There is no conceivable way in which I can logically demonstrate to you that the judgments of my conscience are superior to the judgments of your conscience, and vice versa. Many of us necessarily feel strongly and deeply about our own moral judgments, but they remain only personal moral judgments until in some way given the sanction of law.”

Analyzing this passage in a 1994 article in the Rutgers Law Journal, Professor Thomas W. Merrill of Columbia Law School said Justice Rehnquist’s point was that “the only way to choose between moral judgments in a democratic society is to take a vote, and adhere to the judgment endorsed by a majority.”

In later life, Chief Justice Rehnquist cheerfully agreed that he had adhered to the same views over the decades and appeared bemused by the response this sometimes evoked in others. To a questioner in 1994 who asked him whether his thinking on any major legal question had “evolved” over time, the Chief Justice cocked an eyebrow and said in a wry tone: “Do you mean, have I shown a capacity for growth?”

He was eventually able to transform long-held views into the law of the land. In 1952, after his graduation from Stanford University Law School, he took a coveted job as a law clerk to a Supreme Court justice, Robert H. Jackson. In one memo to the justice suggesting what the court should do with a pending criminal case, the young clerk argued that the court should abandon its rule that called for automatically reversing a conviction if a confession had been coerced. The evidence in the appeal before the court showed that the three defendants were “guilty as sin,” and the fact that their confessions may have been coerced should be disregarded as “harmless error,” he said.

The court did not take the law clerk’s advice, but in 1991 Chief Justice Rehnquist wrote the opinion for the court in a case called Arizona v. Fulminante, holding for the first time that coerced confessions could be admitted as “harmless error” if other evidence was sufficient to establish guilt.

He wrote opinions in almost every area of the law. Among his most important opinions were those that set limits on the meaning of the Constitution’s due process guarantee, declining to expand the boundaries of due process in a way that would create new rights or encroach on state power. These decisions marked an important shift by the Court away from a period of great expansion of the concept of constitutional due process.

For example, his majority opinion in a 1976 case, Paul v. Davis, held that a man who had been falsely identified as a convicted shoplifter in a flyer circulated by the Louisville, Ky. police department could not sue the police chief for violating the 14th amendment’s guarantee of due process of law. The man might well have a valid case for defamation in the Kentucky state courts, Justice Rehnquist wrote, but to permit him to sue under the Constitution in federal court “would make of the 14th Amendment a font of tort law to be superimposed upon whatever systems may already be administered by the States.”

In similar fashion, a 1989 majority opinion, DeShaney v. Winnebago County, rejected the argument that state-employed social workers deprived a young boy of his right to due process by leaving him in the care of an abusive father who then beat him into an irreversible coma. The purpose of the due process guarantee, Chief Justice Rehnquist wrote, “was to protect the people from the State, not to ensure that the State protected them from each other.” He added: “The Framers were content to leave the extent of governmental obligation in the latter area to the democratic political processes.”

A 1979 majority opinion, Bell v. Wolfish, held that it did not violate the Constitution for prison officials to place two prisoners in a cell designed for one. There is not “some sort of one-man, one-cell principle lurking in the due process clause,” Justice Rehnquist wrote.

A Shift in Power

His majority opinions could be cryptic, sometimes only hinting at the legal reasoning, let alone the broader context or implications of the ruling. He was a fast and prolific writer, whose efforts to spur his colleagues to similar levels of speed and productivity were often disappointed.

He staked his ground early in the debate over the boundary between state and federal authority. His majority opinion in a 1976 case, National League of Cities v. Usery, invalidated the application of federal minimum wage and hour requirements to employees of state and local governments. While a narrow majority overturned that decision, over Justice Rehnquist’s dissent, nine years later in Garcia v. San Antonio Transit, the 1976 opinion had the important effect of reviving interest in the 10th Amendment. That amendment, previously one of the most obscure provisions of the Bill of Rights, reserves to the states or “to the people” any powers not explicitly given elsewhere in the Constitution to the federal government.

The 1976 decision put federal regulatory authority on the defensive as it had not been for a generation. Chief Justice Rehnquist’s majority opinion in United States v. Lopez in 1995 raised the stakes in the debate over federal authority even higher. The decision declared unconstitutional a Federal law, the Gun Free School Zones Act of 1990, that made it a federal crime to carry a gun within 1,000 feet of a school.

His focus in the Lopez decision was on a different constitutional provision, the Commerce Clause, for more than half a century the source of nearly unquestioned authority for Congress to oversee national affairs.

He said that because the possession of guns near schools “has nothing to do with ‘commerce’ or any sort of economic enterprise, however broadly one might define those terms,” Congress lacked authority to pass the law under its constitutional power to regulate interstate commerce. The decision marked the first time since the New Deal that the Court had invalidated an exercise by Congress of its commerce authority.

The four dissenters objected both that guns moved in interstate commerce and that gun-related crime contributed to a national economic problem, but the chief justice’s five-member majority insisted that Congress had gone too far.

The Lopez case was followed by a series of decisions expanding state immunity from federal regulation and constricting the authority of Congress. Nearly all were decided by 5-to-4 votes. Justices Sandra Day O’Connor, Anthony M. Kennedy, Antonin Scalia, and Clarence Thomas were his reliable allies in the Rehnquist Court’s federalism revolution.

As chief justice, he was outspoken in his impatience with Supreme Court precedents with which he disagreed. A 1991 majority opinion, Payne v. Tennessee, was essentially a manifesto for overruling precedents. In that case, the court overruled two earlier rulings that had barred prosecutors in death penalty cases from introducing evidence about the impact of the crime on the victim’s family and community.

In his opinion, Chief Justice Rehnquist described general categories of precedents most suitable for overruling: constitutional cases, which unlike cases interpreting statutes cannot be corrected by Congress if they are in error; cases involving rules of evidence or procedural rights, in which people have no vested economic interest; and cases that have been decided “by the narrowest of margins, over spirited dissents challenging the basic underpinnings of those decisions.”

Spirited in Dissent

Many of his own dissents over the years could easily be described as spirited, although he toned down his rhetoric after he became chief justice. The fact that no one else agreed with him was no deterrent to publishing a strong dissent. In fact, when he was nominated to be chief justice, he was the court’s most frequent lone dissenter, and some senators wondered aloud whether he could work effectively with his colleagues. Those concerns soon proved groundless.

He was the only dissenter in a high-profile 1983 case, Bob Jones University v. United States, in which the court upheld the refusal of the Internal Revenue Service to grant tax-exempt status to a private university with racially discriminatory policies for student behavior – a ban on interracial dating or marriage. In dissent, Justice Rehnquist argued that while “I have no disagreement with the Court’s finding that there is a strong national policy in this country opposed to racial discrimination,” Congress had not given the I.R.S. authority to deny tax-exempt status on that basis.

In a 1985 religion case, Wallace v. Jaffree, he dissented from the court’s decision to strike down an Alabama law that provided a daily moment for silent prayer in the public schools. He said the court’s modern precedents on religion were wrong, based on what he said was a misguided belief that the Constitution’s framers meant to erect a “wall of separation” between church and state. All the framers had intended, he said, was to prohibit the establishment of a national religion and to forbid preferential treatment of one denomination over another, not to make the government neutral “between religion and irreligion” or to prevent government aid to religion on a nondiscriminatory basis.

In Chief Justice Rehnquist’s entire tenure on the court, there was no decision more disputed than Bush v. Gore, the 5-to-4 ruling that ended the 2000 presidential election as well as the bizarre 34-day post-election period of lawsuits and recounts.

The initial question for the Supreme Court was whether to get involved at all in the dispute between the two candidates, Vice President Al Gore and Mr. Bush, then the governor of Texas, over the inconclusive outcome of the election in Florida, where it was clear that the state’s 25 electoral votes would determine the outcome of the election despite Mr. Gore’s majority in the nationwide popular vote. Mr. Bush held an evanescent lead in Florida, fewer than 2,000 votes on election night out of nearly 6 million cast and only 327 after an initial machine recount, a margin that Mr. Gore threatened to erase in a recount ordered by the Florida Supreme Court.

As November became December with no official winner, it appeared that election night would never end. But the events that led to the final decision were extraordinarily compressed. On Dec. 9, the day after the Florida Supreme Court ordered a new recount, the chief justice and Justices Scalia, O’Connor, Kennedy, and Thomas voted to issue a stay, freezing the recount that had just begun. They also accepted the Bush appeal and scheduled argument for Dec. 11. Through the night after the argument and the long day that followed, the country waited for the result. At 10 p.m. on Dec. 12, the court issued its ruling. An unsigned opinion by the same five justices held that a lack of uniform standards for counting ballots from county to county meant that the recount would violate the constitutional guarantee of equal protection. There was no time to fix the problem, the majority held, so there could be no further counting.

Chief Justice Rehnquist wrote a concurring opinion, which Justices Scalia and Thomas also signed, arguing that the Florida Supreme Court had usurped the state legislature’s authority, under the Constitution and a federal statute, to determine the rules for conducting elections.

The decision was tremendously controversial. Its defenders maintained that whatever the analytical deficiencies of the majority opinion, the court’s intervention had the benefit of sparing the country further uncertainty that was on the verge of turning into a real crisis. The court’s critics called the decision an activist and basically partisan act; it was unseemly, they said, for justices to be selecting the president who foreseeably would be in the position to choose their own successors. Whatever the merits of this debate, predictions that the Supreme Court would plummet in the public’s esteem proved unfounded, and the country, if not the legal academy that produced a shelf of books on the episode, soon moved on.

Chief Justice Rehnquist often said that he was strongly influenced in his world view by a book he read as a young man, “The Road to Serfdom,” by Friedrich von Hayek, the Austrian-born, Nobel Prize-winning economist. A best-seller after its publication in 1944, the book warned of the dangers of collectivism and big government and predicted that socialism, the “road to serfdom” of the title, would eventually collapse.

But his political opinions were by many accounts formed years earlier, in the secure, middle-class household where he grew up with a younger sister, Jean, in Shorewood, Wis., a suburb of Milwaukee. William Hubbs Rehnquist was born in Milwaukee on Oct. 1, 1924. His paternal grandparents had immigrated from Sweden to the Chicago area. His father, William Benjamin Rehnquist, worked in the paper business as a wholesale broker to the graphic arts industry. His mother, Margery Peck Rehnquist, was fluent in several languages and worked part-time as a translator for local companies.

His parents were conservative Republicans. President Hoover was admired in the household. Franklin D. Roosevelt distinctly was not. Young Bill Rehnquist’s classmates from those days later told interviewers that his political conservatism was distinctive. He did well in high school, graduating in 1942 with a scholarship to Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio. But he left after a few months to enlist in the Army Air Corps. He did not see combat during World War II. He spent time in North Africa as a weather observer and was discharged in 1946 with the rank of sergeant.

He had been sufficiently impressed with the North African climate to decide that he did not want to return to the Midwest. He attended Stanford University on the G.I. Bill, graduating in 1948 as a member of Phi Beta Kappa with both a bachelors and masters degree in political science. He went to Harvard to continue his graduate studies, but complained to friends about “Harvard liberalism.”

On something of a whim, he took the law school aptitude test and did extremely well. Leaving Harvard with a second masters degree, he entered law school at Stanford on a scholarship and graduated first in his class in 1952 with his Supreme Court clerkship in hand. The No. 3 class ranking was held by a young woman from Arizona named Sandra Day, later to be his Supreme Court colleague, Sandra Day O’Connor.

In his book “The Supreme Court: How It Was, How It Is,” the chief justice described driving to Washington, where he had been only once before, in his 1941 Studebaker to start his 18-month clerkship. The book is an account of some of the court’s famous cases and aside from some anecdotal material is not a personal memoir. But it offers a vivid depiction of the combination of enthusiasm and awkwardness with which the young lawyer began the next phase of his life. He described his curiosity about what his working hours would be but his reluctance to ask even his fellow law clerk, who had already been there for some months, “because it somehow seemed to indicate less than complete devotion to the job.”

The Brown Case

Justice Jackson, who served on the court from 1941 until his death in 1954, had been a close adviser to President Roosevelt, serving as solicitor general and attorney general. During his Supreme Court tenure, he also served as the chief United States prosecutor at the Nuremberg war crimes trials in 1945 and 1946.

The young law clerk admired his justice although there was much on which they disagreed. A memo that clerk Rehnquist wrote for Justice Jackson in 1952 on the school desegregation cases then before the Court, including Brown v. Board of Education, came back to haunt him at both his own Supreme Court confirmation hearings.

Entitled “A Random Thought on the Segregation Cases,” the memo argued that the attack on school segregation should be rejected and the separate-but-equal doctrine the Court had endorsed in the notorious Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896 “was right and should be reaffirmed.”

“I realize that it is an unpopular and unhumanitarian position, for which I have been excoriated by my ‘liberal’ colleagues,” Mr. Rehnquist wrote to Justice Jackson. He also wrote that “in the long run it is the majority who will determine what the constitutional rights of the minority are.”

The memo, which remained in Justice Jackson files, caused a furor when it surfaced during Mr. Rehnquist’s 1971 confirmation hearing. Both then and during his 1986 hearing on his nomination to be Chief Justice, he said that the memo did not express his personal view, but had been drafted at Justice Jackson’s request as a summary of the Justice’s views.

“I fully support the legal reasoning and the rightness from the standpoint of fundamental fairness of the Brown decision,” Mr. Rehnquist said at his 1971 hearing.

In 1953, he married Natalie Cornell, a fellow Stanford graduate who was then working in Washington for the Central Intelligence Agency. They had a son, James, and two daughters, Janet and Nancy. It was a strong marriage and Mrs. Rehnquist, who was known as Nan, was very popular at the Court. She died in 1991 after a long battle with cancer.

Chief Justice Rehnquist is survived by three children: Janet Rehnquist of Arlington, James C. of Sharon, Mass., and Nancy Spears of Middlebury, Vt.; his sister, Jean Larin of Grand Rapids, Mich.; and nine grandchildren.

After his clerkship ended, the Rehnquists chose Phoenix as a place to settle. He joined a law firm there and became active in Republican politics and in civic affairs. In a 1957 speech to a local bar association, he criticized liberal Justices on the Warren Court for “making the Constitution say what they wanted it to say.” He also spoke publicly against a proposed local law barring racial discrimination in public accommodations and against an integration plan for the Phoenix public schools. He campaigned in 1964 for the conservative Republican Presidential nominee, Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona.

He became friendly with Richard G. Kleindienst, a Phoenix lawyer who helped run Nixon’s successful presidential campaign in 1968. When Mr. Kleindienst went to Washington as Deputy Attorney General, he recommended Mr. Rehnquist for a job. As assistant attorney general for the Office of Legal Counsel, Mr. Rehnquist was suddenly in a high-profile position, testifying often before Congress to give the Nixon Administration’s views on obscenity, wiretapping, national security and other sensitive subjects.

He thrived in the Justice Department, entranced by the sense of immediacy and by wrestling with the great issues of the day. Years later, as chief justice, he described his three years there with evident nostalgia as the high point of his professional life.

He had very little contact with the president himself. In one of the Watergate tapes, Nixon was recording as referring to “that group of clowns” at the Justice Department, “Renchburg and that group.” According to an account by John W. Dean, Nixon’s White House counsel, Nixon stopped by briefly at a meeting that Mr. Rehnquist was running and later summoned his counsel to ask: “John, who the hell is that clown?”

“I beg your pardon?” Mr. Dean replied.

“The guy dressed like a clown, who’s running the meeting,” the president said in an evident reference to Mr. Rehnquist’s pink shirt and clashing psychedelic necktie.

Nonetheless, Nixon nominated him in October, 1971 to a Supreme Court vacancy caused by the retirement of Justice John M. Harlan.

The nomination of Mr. Rehnquist as well as the simultaneous nomination of Lewis F. Powell Jr., a former president of the American Bar Association, to succeed Justice Hugo L. Black was a last-minute affair. The American Bar Association indicated that it would not approve the original choices for the two vacancies and the administration wanted to avoid a protracted struggle.

While Mr. Powell was easily confirmed, the confirmation process for Mr. Rehnquist was much more acrimonious. His hearing lasted five days. Liberal senators as well as civil rights leaders denounced him as a right-wing extremist. The final vote was 68 to 26, and Mr. Rehnquist took his seat as the 100th Justice on Jan. 7, 1972.

His confirmation hearing to become chief justice nearly 15 years later was something of a rerun. President Reagan named him on June 17, 1986, to succeed Warren E. Burger, who retired from the Court to head the national commission in charge of the bicentennial celebration of the Constitution. Questions at the Rehnquist confirmation hearing ranged over his political activities in Arizona, to the advice he gave the Nixon Administration, to a racially restrictive – and legally unenforceable – covenant on the deed to his Vermont vacation house.

The Judiciary Committee also reviewed his medical record, which included the use for nine years of increasing doses of a prescribed hypnotic drug, Placidyl, to help him sleep while suffering severe back pain. He had been hospitalized for 10 days in late 1981 to be weaned off the drug, which had caused side effects including slurred speech.

Few minds were changed during the prolonged debate, and the Republican-controlled Senate confirmed him to be chief justice by a vote of 65 to 33 on Sept. 17, 1986. At the same time, Antonin Scalia was confirmed by a vote of 98 to 0 to the seat he was vacating as an associate justice. The two men were sworn in on Sept. 26.

While the new chief justice found the confirmation process extremely disagreeable, he kept his composure and even his wry sense of humor. At one point, a Republican Senator, Orrin G. Hatch of Utah, commended him for his recent dissent in Wallace v. Jaffree, the case on silent prayer in the Alabama public schools. Senator Hatch observed that the Senate Judiciary Committee had voted for a constitutional amendment to allow such prayer. “What you have been labeled extreme for, is something a majority of this committee supports,” Senator Hatch said.

Justice Rehnquist smiled and shrugged. “We’re all extremists together,” he said.

Rehnquist to Lie in Repose at High Court

Sunday, September 4, 2005

Chief Justice William Rehnquist’s body will lie in repose in the Great Hall of the Supreme Court on Tuesday and Wednesday and he will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery following funeral services Wednesday.

The court announced Sunday that the public will be invited to pay its respects from 10:30 a.m. EDT until 10 p.m. on Tuesday and from 10 a.m. until noon on Wednesday.

Funeral services will be at 2 p.m. at St. Matthew’s Cathedral in Washington, D.C., with funeral services open to friends and family. The burial at Arlington will be private.

In a sensitive ritual, Supreme Court officials and the Military District of Washington coordinated the funeral arrangements with Rehnquist’s family.

Timing and other details were in the hands of the family, said Barbara Owens, a spokeswoman for the Army’s Joint Force Headquarters National Capitol Region/Military District of Washington.

Rehnquist died Saturday at the age of 80 and the Supreme Court announced the arrangements Sunday evening.

The bodies of Rehnquist’s two immediate predecessors, Warren E. Burger and Earl Warren, also are buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Burger and Warren lay in repose in the Supreme Court Building before their services.

The casket of the last chief justice to have died, Burger in 1995, was carried up the marble steps of the building, where it was on public view for 12 hours before services at National Presbyterian Church.

President Clinton, the nine members of the Supreme Court and four former justices were among the 800 people who attended.

As chief justice, Rehnquist is entitled to a state-sponsored official funeral, a ceremony that includes a 19-gun salute, four ruffles and flourishes from drums and bugles, and the last 32 bars of the John Philip Sousa march “Stars and Stripes Forever” among other military honors.

President Bush could have petitioned Congress for a state funeral for Rehnquist, a ceremony that would have allowed the body to lie in state in the Rotunda of the Capitol. Only state funerals include that honor.

The most recent state funeral was accorded President Reagan in 2004. The last official funeral was conducted for Commerce Secretary Ron Brown in 1996.

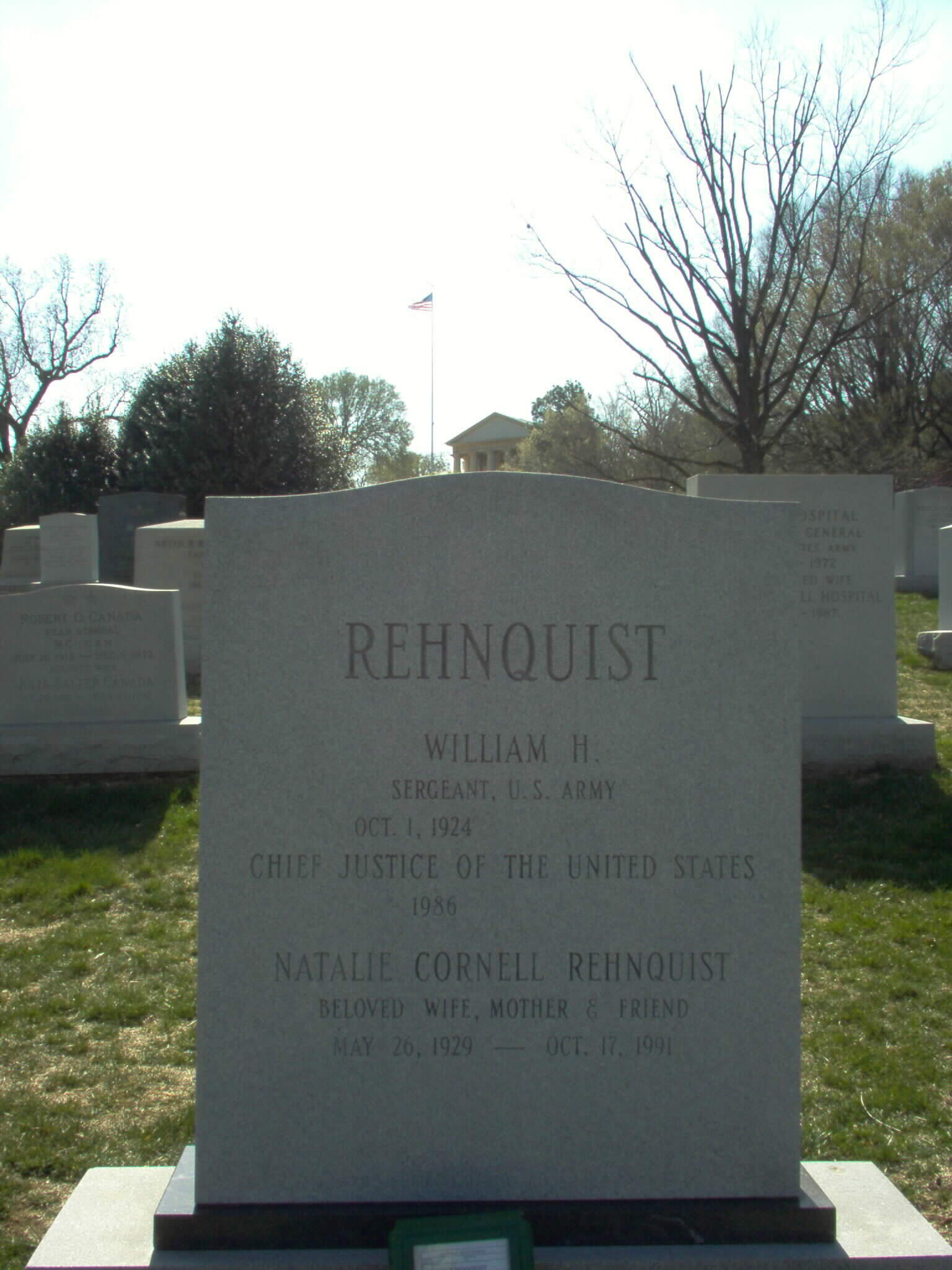

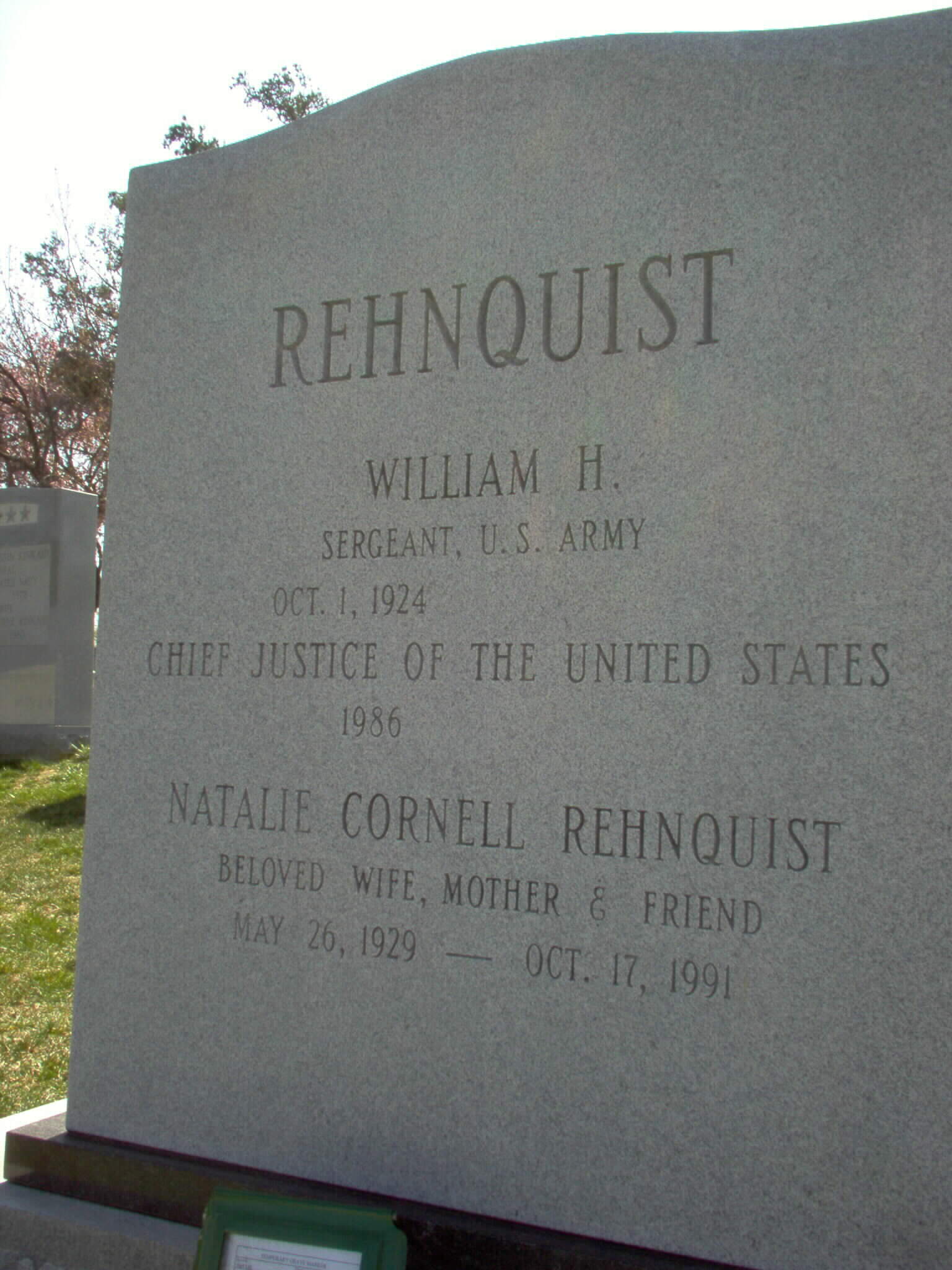

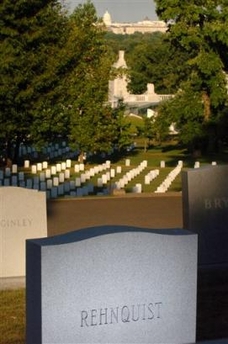

Chief Justice Rehnquist’s wife, Natalie C. Rehnquist, is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

7 September 2005:

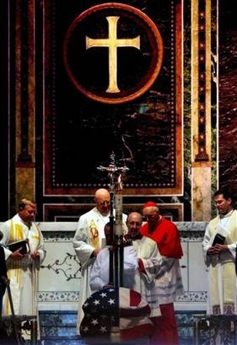

Chief Justice William Rehnquist was laid to rest yesterday at Arlington National Cemetery, surrounded by his family and close friends.

President Bush, Vice President Cheney, Supreme Court justices, lawmakers, Cabinet members and other mourners attended Rehnquist’s service at the Cathedral of St. Matthew.

Outside the ceremony, members of the public looked on to pay their respects to the 16th chief justice of the United States.

Each of the eight sitting justices spoke at the funeral, reminiscing about Rehnquist’s impressive and long career as chief justice. They also praised him for his role as a father and his sense of humor.

Washington Archbishop Cardinal Theodore McCarrick recalled the first time he met Rehnquist, at the annual Red Mass in 2001. Rehnquist was known always to attend the mass although he was a devout Lutheran.

Bush and Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, who announced her retirement from the court July 1, were also among those who eulogized Rehnquist, offering anecdotes and admiration for his three decades of his service on the court.

O’Connor, who met Rehnquist while the two were undergraduates at Stanford 50 years ago, told a story about a recent issue that came across the court on which the justices issued seven different opinions.

“I didn’t know we had so many justices,” Rehnquist quipped.

She said his sense of humor continued even into the last week of his life. When the doctor at a local emergency room asked him who his primary-care physician was, Rehnquist replied, “My dentist.”

She and Bush both talked about Rehnquist’s love for playing cards, sports and history.

Bush said, “I stood next to him during the national anthem — he liked to sing.”

“He personified the ideal of fairness, and people sensed it,” Bush said.

The president noted his inauguration earlier this year, when Rehnquist, “weakened by illness, [rose] to his full height and in full voice said, ‘Mr. President raise your right hand and repeat after me.’”

He added that Rehnquist was one of the few in Washington who served for 30 years and “left behind only admiration.”

Two of his three children, James Cornell Rehnquist and Nancy Rehnquist Spears, also spoke at the funeral. His third child, Janet, was also in attendance.

James Rehnquist, who is a lawyer, said his father was a patient man who would tolerate “my diatribes about operating under the law as he had built it.”

Passages from the book of Isaiah and Matthew were among those read at the service. During one of the hymns, “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God,” the Rev. Jeffrey Wilson said Rehnquist not only liked the four-verse hymn but would sing the entire thing through.

Crowds lined 1st Street well before the court opened yesterday to view the justice who was laying in repose there since Tuesday. Members of Congress, including Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist (R-Tenn.), filtered out of the massive hall one by one after paying their final respects. Architect of the Capitol Alan Hantman and Sergeant at Arms Bill Livingood were also among the mourners yesterday.

The doors closed to mourners slightly after noon, and around 12:30 p.m., eight former law clerks served as pallbearers and carried his coffin up the marble stairs. The motorcade soon rolled through the streets of Washington to take Rehnquist’s body to the cathedral.

Rehnquist died Saturday evening in his Virginia home after a long battle with thyroid cancer. He was 80. He is credited as being one of the most influential chief justices in history, actively increasing the role of the court in everyday American life.

Rehnquist presided over the Senate trial of then-President Clinton. He played a pivotal role in the court’s decision that settled the 2000 presidential election. He was known to be staunchly conservative and unwavering in his beliefs.

Rehnquist was born in Milwaukee, Wis., on Oct. 1, 1924. He will be buried next to his wife, Natalie Cornell, who died in 1991. He served in the U.S. Army Air Corps from 1943 to 1946 and received his bachelor’s, master’s and L.L.B. degrees from Stanford . He received an M.A. from Harvard University.

President Nixon nominated him to the Supreme Court in 1972. He served as an associate justice for 15 years until President Ronald Reagan nominated him as chief justice in 1986.

Rehnquist’s predecessors Warren Burger and Earl Warren also are buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Bush has nominated federal appeals-court Judge John Roberts Jr. to replace Rehnquist. His confirmation hearings are scheduled to begin next week.

Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist was buried Wednesday as President Bush led the nation in bidding farewell to the man who orchestrated a dramatic states rights power shift in a third of a century on the Supreme Court and settled the acrimonious 2000 election in Bush’s favor.

With more laughs than tears, family and friends spoke poignantly of Rehnquist’s final days — when he cracked jokes in the face of death — and proudly of the imprint of his 33 years on the high court.

“We remember the integrity and the sense of duty that he brought to every task before him,” Bush told the funeral audience during a two-hour service at historic St. Matthew’s Cathedral. Rehnquist was a steady, guiding presence on the court, Bush said of the nation’s 16th chief justice who died last Saturday at 80.

The service drew Washington’s power elite, including the eight Supreme Court justices and John Roberts, a former Rehnquist law clerk whom Bush has named to succeed him.

Rehnquist, a veteran of the Army Air Forces in World War II, was buried in a private ceremony in Arlington National Cemetery in a grave not far from those of several other justices. His headstone was not yet engraved. From the grave site, where his wife was buried in 1991, the Capitol is visible.

Despite battling thyroid cancer, Rehnquist managed to attend Bush’s second inauguration in January — a gesture the president recalled with appreciation. “Many will never forget the sight of this man, weakened by illness, rise to his full height and say in a strong voice, `Raise your right hand, Mr. President, and repeat after me,'” Bush said.

The chief justice, a solid conservative, was leader of the “Rehnquist five” who often favored states rights over federal government power, and in a bitter 5-4 vote handed Bush the 2000 election. There was only passing mention of that during the service, as well as his duties presiding over President Clinton’s impeachment trial in 1999.

Instead, friends and family talked about his penchant for wagers, jokes, sports, geography, history, tennis, and competition of any type.

“If you valued your money, you would be careful about betting with the chief. He usually won,” said Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, who dated Rehnquist when both were in law school together in the 1950s. “I think the chief bet he could live out another term despite his illness. He lost that bet, as did all of us, but he won all the prizes for a life well lived.”

Comparing Rehnquist to an expert horse rider, O’Connor said, “He guided us with loose reins and used the spurs only rarely.” He was, she added, “courageous at the end of his life just as he was throughout his life,” even joking with doctors in a final visit to the hospital.

The service, scripted in part by the chief justice before his death, had a light touch. A granddaughter talked about learning poker tips from him. His son said his dad “could forgive almost anything in a person except being humorless.”

“No one smelled more roses than my dad,” James Rehnquist told the funeral audience.

Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, in a welcome to those assembled in the Roman Catholic church, praised Rehnquist as a “loving father and husband, an outstanding legal scholar, a tireless champion of life and a true lover of the law: in every sense, a great American.”

Said Bush, “To work beside William Rehnquist was to learn how a wise man looks at the law and how a good man looks at life.”

Rehnquist’s flag-draped casket was brought to the church from the court, where he had lain in repose since Tuesday morning. Long lines had formed at the court to file past.

Cabinet officers and other Washington dignitaries filled St. Matthew’s as trumpeters played. President Kennedy’s funeral was held at the church in 1963, and Pope John Paul II celebrated Mass in 1979.

The family of Rehnquist, a Lutheran, requested St. Matthew’s primarily because of the space the Roman Catholic church provided.

At the service, Nancy Rehnquist Spears joked about her father’s history quizzing and his love of games and gambling. She recalled him promising $5 if she could tell the history buff when Queen Elizabeth died.

“1603,” she answered.

“There was silence, then a muffled curse,” she recalled. “Five dollars was not a lot of money, not now, not then, but my father spent the rest of the summer trying to win it back from me.”

Bush initially nominated Roberts, a federal appellate judge, to replace O’Connor, who announced in July that she would step down.

After Rehnquist’s death the president chose Roberts to be the nation’s 17th chief justice instead and said that the list of possible nominees for O’Connor’s seat was wide open.

Bush and Senate Republicans are pushing to confirm Roberts before the new court session that begins Oct. 3. Democrats have cautioned against a rush to approval now that Roberts is a candidate for chief justice and at age 50, could shape the court for decades.

Flags, including the one above the court, were at half-staff in honor of Rehnquist, who was appointed by President Nixon and then elevated to chief justice in 1986 by President Reagan.

WASHINGTON, Sept. 7 – At funeral services for Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist this afternoon, friends and family members recalled his intellectual rigor, as well as his zest for life. And almost everyone had a story about his love of a good wager.

William H. Rehnquist led a conservative revolution on the Supreme Court.

At the historic St. Matthew’s Cathedral in downtown Washington, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor talked about the first time she met the man who would become chief justice, when she was a freshman at Stanford University 59 years ago. He was an upperclassman working as a “hasher,” essentially a busboy in the student dining room.

Everyone already knows the two had a few dates, and that both went on to marry other people, while remaining good friends.

What most people did not know about him, Justice O’Connor said, except if you were in his family, a close friend or working within the lofty confines of the high court, was that “the chief was a betting man.”

“He enjoyed making wagers about most things, the outcome of football or baseball games, elections, even the amount of snow that would fall in the courtyard at the court,” she said during the services.

“If you valued your money, you would be careful about betting with the chief,” she said. “He usually won.

“I think the chief bet he could live out another term despite his illness,” she said. “He lost that bet, as did all of us, but he won all the prizes for a life well lived.”

Chief Justice Rehnquist, who had suffered from thyroid cancer, died on Saturday at age 80.

Several cabinet officers and other Washington dignitaries were on hand for the services, which in the same church where President John F. Kennedy’s funeral was held in 1963 and Pope John Paul II celebrated Mass in 1979. The grandson of Swedish immigrants, Chief Justice Rehnquist was Lutheran, not Roman Catholic. But his services were held at the cathedral, instead of at the smaller Lutheran Church of the Redeemer, Justice Rehnquist’s church in northern Virginia, because of the size of the crowd expected today.

President Bush asked the nation to remember the kindness and integrity of the chief justice’s life, including his 33 years on the high court.

“We remember the integrity and the sense of duty that he brought to every task before him,” Mr. Bush said.

The president recalled that in spite of suffering from thyroid cancer, the chief justice attended Mr. Bush’s second inauguration in January and administered the oath of office to him

The chief justice’s son and daughter, James Rehnquist and Nancy Rehnquist Spears, recalled playing countless rounds of cards and charades with their father, the geography lessons he tried to drill into them, and his 50-year-old unbroken streak of attending a December performance of the Messiah, no matter where he was, or how he was feeling, including a performance last December, when he was already weakened by the cancer that finally took his life.

James Rehnquist told of his own graduation from high school in McLean, Va., when his father, newly appointed by President Nixon to the high court, was asked to give the commencement address. The country was riven by the Vietnam War at the time, his son recalled, and some of his fellow students wondered “what could this force of darkness possibly send as a message to our graduating class?”

His father spoke to the class about “how important it was to smell the roses,” he recalled.

Afterward, he said, one of his classmates, whom he described as being in the “make love, not war camp,” came up to James and said, “Rehnquist, your dad’s cool.”

“I think it’s safe to say that no one smelled more roses than my dad,” Mr. Rehnquist said.

Nancy Rehnquist Spears talked about how her father would find joy in the most mundane of objects, including “a perfectly ripe pear, arousing him to sing.” She said he was religious about taking his vacations, which he relished, and of course loved to bet, even with his own children.

One year, she recalled, he told her he would give her $5 if she could tell him when Queen Elizabeth I died. Having just read a book on the queen, Ms. Spears shouted out, “1603!”

She said she heard a muffled curse from his bedroom, and he spent the rest of the summer trying to win the $5 back from her.

The chief justice was to be buried at Arlington National Cemetery, where his wife, who died in 1991, is also buried.

Chief Rehnquist’s body lay in repose for two days in the great hall of the high court, where he served for 33 years, and before several of his law clerks carried his coffin out this afternoon to transport it to the church, ministers from his church offered a benediction.

“Thank you for the role he has played in our lives, his influence among us,” said the Rev. Jeffrey Wilson.

This afternoon, hundreds of people stood in front of the Supreme Court and watched as the eight Supreme Court Justices walked somberly out of the high court, heads bowed and their dark clothes in stark contrast to the white marble steps in the bright sun of the capital, with the pallbearers following behind.

In the final hours of viewing, members of the United States Senate paid tribute to Justice Rehnquist, praising him as one of the nation’s finest chief justices who oversaw the Supreme Court’s work with dignity and dispatch.

“He kept the members of the court together, despite their many differences,” said Senator George V. Voinovich, Republican of Ohio, according to The Associated Press.

Senator Pete V. Domenici, Republican of New Mexico, called Justice Rehnquist “a great intellect who matured tremendously” during his more than three decades of service on the Supreme Court.

The Senate passed a resolution, by 95 to 0, today honoring Chief Justice Rehnquist. The House passed a similar resolution, and both houses recessed so members could attend the funeral.

On Tuesday, Judge John G. Roberts Jr., whom the president has nominated to succeed the chief justice, had helped to carry the coffin into the court building and place it on the historic Lincoln Catafalque, on which President Lincoln’s coffin once lay.

Judge Roberts, a clerk for then-Associate Justice Rehnquist 25 years ago, was one of eight pallbearers. The others were a former administrative assistant to the chief justice, James Duff, and six other former law clerks: David G. Leitch, Frederick W. Lambert, Ronald J. Tenpas, Kerri Martin Bartlett, Gregory G. Garre and John C. Englander.

Dozens of other clerks who served the chief justice during his 33-year tenure also joined family members and six of the current justices in paying respects, standing by the white-pine coffin at a brief prayer service that Mr. Evans led before the court was opened to the public.

Along with Justices Antonin Scalia and O’Connor, Justices John Paul Stevens, Clarence Thomas, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen G. Breyer were present for the service. Justice Anthony M. Kennedy was returning from China, and Justice David H. Souter from New Hampshire. All the justices attended the funeral.

Bush, O’Connor Pay Tribute to Rehnquist

By Charles Lane

Courtesy of the Washington Post

Thursday, September 8, 2005

President Bush led official Washington yesterday in remembrance of Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist at a funeral service that offered an unusual personal glimpse of a man whose 33-year Supreme Court tenure made him one of the more consequential figures in U.S. judicial history.

“Many will never forget the sight of this man, weakened by illness, rising to his full height and saying, ‘Raise your right hand, Mr. President, and repeat after me,’ ” Bush said, referring to Rehnquist’s appearance at Bush’s swearing-in on Jan. 20, three months after the chief justice first learned that he had thyroid cancer. Rehnquist died at 80 on Saturday.

The service took place at the Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle in Northwest Washington, and Rehnquist was later laid to rest in a private burial at Arlington National Cemetery.

His friend of more than five decades, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, spoke admiringly of his leadership as chief justice, after he was elevated to that job by President Reagan in 1986. “He never twisted arms to get a vote on a case,” she said. Instead, like the expert horsemen on the ranch where she grew up, “he guided us with loose reins and used the spurs only rarely.”

For the most part, however, the chief justice’s official persona was not the focus of the two-hour service, which was attended not only by the president and first lady Laura Bush but also by Vice President Cheney and his wife, Lynne, all eight associate justices of the court, the Republican and Democratic leaders of the Senate, federal judges, dozens of the chief justice’s former law clerks, and members of his Lutheran congregation.

Hardly any mention was made of the content of the many opinions he wrote on the court, or of the deep and often controversial impact on the law he had during a Supreme Court tenure that began with his nomination as an associate justice by President Richard M. Nixon in 1971.

Rather, amid frequent laughter, speaker after speaker recalled the chief justice’s rich personal and family life, a life that was, as they told it, free of conflict but full of jokes, family vacations and parlor games.

What emerged from the eulogies was a kind of parallel biography separate and distinct from his amply documented official record — and much different from the sometimes stern face he showed while running oral arguments at the court. The service made it plain that Rehnquist had left as much of an impact on his loved ones as he did on the country, if not more.

Rehnquist, Bush said, “was devoted to his public duties but not consumed by them.”

“To say that family came first with my Dad is to say there was competition. There wasn’t,” said Nancy Spears, his daughter.

Among the new insights was the fact that Rehnquist, music lover, first suspected his illness when he found that he couldn’t sing hymns at church, according to the Rev. George W. Evans Jr., pastor of the Lutheran Church of the Redeemer in McLean, where Rehnquist attended services for many years.

Evans also said in his sermon that as recently as “a week ago Monday” Rehnquist was still intending to return to the court for the term that begins Oct. 3.

O’Connor, who recalled first meeting the future chief justice when he was busing tables at a Stanford dining hall during their student days, remembered an unpublicized emergency room visit in the last week of his life, when a physician asked him who his primary care doctor was.

“My dentist,” Rehnquist quipped.

Perhaps the most touching account of Rehnquist’s family life came from Rehnquist’s granddaughter, Natalie Ann Rehnquist Lynch, who has the same first name as Rehnquist’s late wife.

She read from a letter she had written to him earlier this summer, noting that, before he died, the chief justice had asked her to read it at his funeral.

Lynch, a high school student, spoke of Rehnquist’s passion for croquet games with his grandchildren and his taste for bologna sandwiches with jelly and mayonnaise.

He would offer a “shiny quarter” to any child who could memorize all 50 state capitals, and he taught them that they could sometimes improve their chances at cards by looking at a reflection of their opponent’s hand in a window, Lynch said.

Rehnquist’s son, James, said that “no one smelled the roses more than my Dad.” He said that, during Rehnquist’s time in Washington, he made it home for dinner with his family by 7:15 p.m. For half a century, Rehnquist had never missed a performance of Handel’s “Messiah” at Christmas time.

He also revealed that Rehnquist, “vaguely dissatisfied” with law practice in 1968, bought a house in Colorado, “built a weird boat” and took his family for a summer of picking fruit alongside migrant workers.

James Rehnquist said his father considered making the new lifestyle permanent but changed his mind and eventually went to Washington in 1969 as assistant attorney general in the Nixon administration.

Spears spoke of her father’s ability to enjoy the simple pleasures in life, from “a ripe pear” to “a distant view of the mountains.”

She said that she once asked her father, whose competitive spirit on the tennis court compensated for his modest natural talent, if it was true that he selected law clerks based on their potential as doubles partners for him.

“Not at all,” he replied. “That’s one of several factors.”

Another of the chief justice’s favorite pastimes was betting on sports, elections and, as O’Connor recalled, “even the amount of snow that would fall in the courtyard at the court.”

“I think the chief bet he could live out another term despite his illness,” O’Connor said. “He lost that bet, as did all of us, but he won all the prizes for a life well lived.”

Later, as she left the cathedral with the other justices, O’Connor whispered a single word to reporters: “Sad,” she said.

Rehnquist was opposed to allowing televised proceedings of the high court, and the same rule prevailed at his send-off. At the request of Rehnquist’s family, television cameras were barred from the cathedral. Nor was there any live audio coverage.

Though Rehnquist was a Lutheran, the service took place at a Catholic cathedral after Cardinal Theodore E. McCarrick, the archbishop of Washington, had offered the building to accommodate the large congregation.

Chief justice laid to rest

Of all the statements made about Chief Justice William Hubbs Rehnquist during his funeral at St. Matthew’s Cathedral in Washington on Wednesday, the most fitting may have been the casket in which he was buried.

It was crafted of unvarnished knotty pine, and it spoke volumes about Rehnquist’s personality and style: Austere. Dignified. Commanding.

President Bush and Justice Sandra Day O’Connor led the nation’s farewell to the 16th chief justice, who was celebrated not only as a top jurist but also as a father, grandfather and close friend.

“In every chapter of his life, William Rehnquist stood apart for his powerful intellect and clear convictions,” Bush said. “He carried himself with dignity, but without pretense. Like Ronald Reagan, the president who elevated him to chief justice, he was kindly and decent, and there was not an ounce of self-importance about him.”

Hundreds packed the cathedral for the private funeral.

Rehnquist’s casket, which had been on display at the Supreme Court, was preceded into the chapel by the eight associate Supreme Court justices and followed by his family.

The audience included many Cabinet members and leaders from the House of Representatives and the Senate, as well as a who’s-who list of high-powered lawyers and conservative activists.

Also in attendance was John Roberts, a former Rehnquist clerk and the man Bush nominated to replace him. Roberts, if confirmed, would be the second-youngest chief justice in history and the first clerk to succeed his former boss.

The Rehnquist family asked to use St. Matthew’s because the chief’s church, the Lutheran Church of the Redeemer in McLean, Va., was too small. After the ceremony, Rehnquist was buried at Arlington National Cemetery, next to his wife, Natalie Cornell Rehnquist, who died in 1991.

Several speakers, including O’Connor, offered warm, personal remembrances that revealed insight into the chief’s personality and his sense of humor, which wasn’t always on public display. Rehnquist maintained an intense privacy during his 33 years on the high court.

Bush noted Rehnquist’s love of music.

“He enjoyed music, and having stood next to him during the National Anthem, I can tell you the man loved to sing,” Bush said.

Rehnquist’s pastor, the Rev. George Evans, said Rehnquist’s inability last year to make the range for church hymns was the chief’s first hint he might be ill.

O’Connor recalled Rehnquist, a close friend she first met when both were enrolled at Stanford University in 1946, as a poignant humorist.

Just last week, she said, as Rehnquist was being examined in the emergency room of a Washington hospital, the doctor asked who his primary physician was. ” `My dentist,’ he struggled to say, with a twinkle in his eye,” O’Connor remembered.

Rehnquist announced last October that he had thyroid cancer. He worked through most of his battle with the disease until he died last week at 80.

On the last day of the term, Rehnquist noted that seven different justices wrote opinions in a contentious Ten Commandments case, and he joked: “I didn’t know we had so many justices on our court.”

“It drew hearty laughter from the spectators,” O’Connor said.

James Cornell Rehnquist described a devoted father who kept work and family in balance. He said his father spoke at his high school graduation in 1973 and won over the class hippies by urging graduates to “smell the roses.”

“I think it’s safe to say that no one smelled more roses than my dad,” he said. “Now, I must say, it’s easier to strike the proper work-life balance when you can do in an hour or two what most people need a couple days to do.”

He said family vacations were “sacred” to Rehnquist. The younger Rehnquist, a lawyer in Massachusetts, said he was reluctant to follow his father into the legal profession. “But, if anything, it’s been even more daunting to follow in his footsteps as a father,” he said.

Daughter Nancy Rehnquist Spears talked about her father’s playful side.

“I hardly remember him working. When he was home, he was always ready to play,” she said.

On the rare occasions when he talked about his work, their mother would warn the children to keep it to themselves.

“We’d roll our eyes and wonder who she thought would possibly be interested,” Spears said.

Photo Coverage Of Funeral Services For Chief Justice Rehnquist

4 September-7 September 2005

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard