Commander of all Forces in Europe during the early stages of World War II, serving with General Dwight D. Eisenhower at times. He was an outspoken proponent of air power.

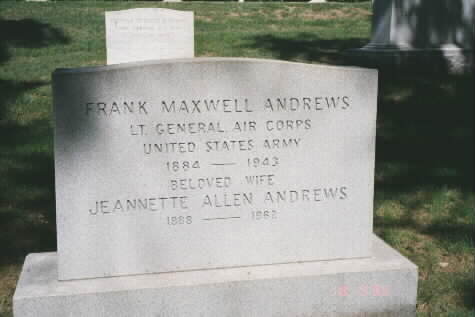

He was born on February 3, 1884 in Nashville, Tennessee and was killed in an aircraft accident in Iceland on May 3,1943. He was buried in Section 3 of Arlington National Cemetery. Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland is named in his honor.

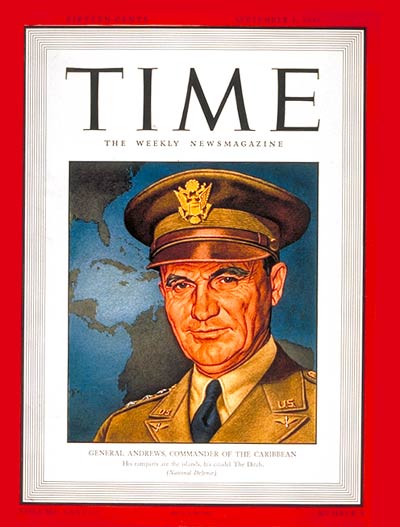

Courtesy of the National Aviation Hall of Fame

ANDREWS, FRANK MAXWELL

Frank M. Andrews was at the center of the long struggle of air-minded officers in the Army who sought to establish an Air Force that could operate co-equally with the ground forces.

He was made first chief of General Headquarters Air Force (GHQ), set up on March 1, 1935 at Langley Field, Virginia, as a combat organization, with a status similar to the Office, Chief of Air Corps, which handled supply and training. During the next four years General Andrews continued in this position to lead the battle for greater organizational independence and for a greater role for the four-engine bomber, the B-17. He sharpened the operational readiness of the air forces with combat-type exercises and record-setting pioneer flights in the United States and Latin America.

During Army-Navy war games in 1938, navigation tests proved that the B-17’s ability to intercept an “enemy aircraft carrier” (the Italian Liner Rex) more than 700 miles east of New York City. Also of great significance, but not publicized, was the air arm’s interception of the Navy battleship Utah in a military exercise in 1937 in bad weather off the coast of California. General Andrews personally directed the operations of GHQ Air Force in both of these exercises; and was a passenger in the B-17 that “bombed” the Utah. (The navigator on both flights was Curtis E. LeMay.)

Constantly General Andrews and his staff found themselves opposed by policies of the General Staff, such as one based on an oral agreement between the Army Chief of Staff and the Chief of Naval Operations in May 1938 that limited the Air Corps to operational off-shore flights of no more than 100 miles.

The muscle-flexing of Hitler and his German Luftwaffe in 1938 had persuaded President Franklin Roosevelt of the decisive potential of airpower and prompted the U.S. Army to prepare a new study of our Hemisphere defenses. The study, submitted to Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall in September 1939, recognized the air threat to the Western Hemisphere and the need for long-range and other aircraft to help defend the Nation. It included for the first time a specific mission for the Air Corps.

General Marshall, who had just replaced General Malin Craig, called General Andrews to Washington to be his Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3, Andrews became the first Air officer to handle the Army’s organization and training.

A year later, in November, General Andrews assumed command of the Panama Canal Air Force. The following September he was made commander of the Caribbean Defense Command and the Panama Canal Department. He was the first Air officer to head a joint command, and one of his greatest tasks was to insure effective coordination of Navy-Army-Air Force and Latin American forces. The system of organization developed there by General Andrews was recommended later to other commanders by the Chief of the Army Air Forces, General H. H. (Hap) Arnold.

In November 1942 General Andrews was assigned to command all United States forces in the Middle East. Several months later he was appointed commander of the United States forces in the European Theater of Operations, with Headquarters in London. In a report to the Secretary of War, General Marshall said that General Andrews, “a highly specialized Air officer,” was assigned this high position after he had been sent to the Middle East “for experience in combat and in contacts with our allies.” The report pointed our that “this order was paralleled by the creation of a North African Theater of Operations, under General Eisenhower.”

Three months later, on May 3, 1942, General Andrews was killed in an aircraft accident in Iceland, while making a trip to installations under his command. He was 59.

Frank Maxwell Andrews was born in Nashville, Tennessee on February 3, 1884. He was graduated from the U.S. Military Academy in June 1906 and appointed a second lieutenant of Cavalry. With the Cavalry he served not only in Virginia, Texas, Vermont, and Hawaii, but in the Philippines, and at Fort Yellowstone, Wyoming and Fort Huachuca, Arizona. In 1917, he transferred to the Signal Corps for duty with the Aviation Division.

It is difficult now to speculate about how great a role General Andrews would have played during World War II and later, if he had lived. One thing is certain, in his 25 years of service in the Air Arm he retained the highest respect of his fellow officers in all the Services while he stimulated great advances in organization, doctrine and weapon systems. As commander of GHQ Air Force for four years he did much to shape today’s Air Force.

Perhaps the greatest tribute ever made to General Andrews was by General Hap Arnold during World War II. He said: “Today, when American bombers fly a successful mission in any theater of war, their achievement goes back to the blueprints of the General Headquarters Air Force. Our operations were based on the needs and problems of our own Hemisphere, with its vast seas, huge land areas, great distances, and varying terranes and climates. If we could fly here, we could fly anywhere, and such has proved to be the case…General Headquarters Air Force was also responsible for our present ideas of organization, maintenance and supply.”

General Andrews made a lasting imprint on the outstanding men on his staff who later became key Air Force leaders – an they, in turn, have made their special marks on the Air Force of today.

— From the General Frank Maxwell Andrews Scholarship in the Air Force Academy.

National Aviation Hall of Fame Biography:

Born in Nashville, Tennessee on February 3, 1884. Of English descent, his father was James David Andrews, a newspaper publisher and real estate dealer, and his mother was Lulu Adaline (Maxwell) Andrews. Andrews attended public grade school in Nashville, and then at age 13, he entered the Montgomery Bell Academy, from which he graduated in 1901. The following year he was appointed to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York on July 31, 1902. He graduated from the Academy on June 12, 1906 and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the U.S. cavalry. Shortly after his graduation from West Point, Andrews sailed for the Philippine Islands, where he began his first tour of duty with the 8th Cavalry at Fort William McKinley in November, 1906.

For the next 11 years, he served with the Cavalry and these years of ground service obviously influenced his subsequent military career. In April 1907, he returned to the U.S. and had duty at several of the legendary forts of the Cavalry. He served at Fort Yellowstone in Wyoming until November, 1908; at Fort Huachuca in Arizona until October 1910; and at Fort Myer in Virginia until November 1910. In January 1911, he arrived in Hawaii and began a three-year tour as aide to Brigadier General Macomb at Schofield Barracks in Honolulu. During this service, he was promoted to first lieutenant on November 12, 1912. Relieved from this duty on June 30, 1913, he returned to the U.S. and served with the 2nd Cavalry at Fort Bliss in Texas. Like many other cavalrymen, Andrews became an ardent and hard-riding polo player. After being detailed to Ft. Ethan Allen in Vermont in December 1913, he met Jeanette Allen, the daughter of General Henry T. Allen. She not only liked horses and polo but she also played polo with Army teams. Even though General Allen is reported to have said that no daughter of his would ever marry an aviator, Andrews became interested in flying during their courtship. But he bided his time and won her hand. They were married on March 18, 1914 and three children were later born to them: Josephine, Allen and Jean.

While Andrews was still serving at Ft. Ethan Allen, he was promoted to captain on July 15, 1916. After the U.S. entered WWI in April 1917, his interest in aviation blossomed. As a result, he transferred to the Signal Corps on August 5, 1917 with the newly acquired temporary rank of major and was assigned to the Aviation Division. After first attending the Field Artillery School of Fire at Fort Sill in Oklahoma, he then reported for duty in the Air Division in the Office of the Chief Signal Officer in Washington, D.C. in September 1917. In working for the Chief Signal Officer, Andrews had an opportunity to observe America’s first large-scale efforts to build up its airpower in accordance with the Aviation Act of 1917. Congress had appropriated $640 million in a belated effort to provide 5,000 warplanes, 4,500 trained pilots and 50,000 mechanics for the war effort by June, 1918. However, he found that while the Chief Signal Officer was responsible for training and organization, he had no control over procurement and operations. As a result of these divided command responsibilities, the aeronautical goals were never fully achieved. However, the lesson was not lost on Andrews, who became a temporary Lieutenant Colonel on January 30, 1918.

In April 1918, Andrews became commander of Rockwell Field on North Island off San Diego. There he finally earned his wings as a Junior Military Aviator in July 1918 at the age of 34, which was considered old. Subsequently, he commanded Carlstrom Field and Dorr Field at Arcadia in Florida. Then in October 1918, he became Supervisor of the Southeastern Air Service District with headquarters in Montgomery, Alabama. After World War I ended in November, 1918, Andrews returned to Washington, D.C. on March 21, 1919, where he became Chief of the Inspection Division and a member of the Advisory Board in the Office of the Director of the Air Service. Then on March 29, 1920, he was assigned to serve with the War Plans Division of the War Dept.’s general staff. During this tour, he reverted to his permanent rank of captain on April 3, 1920, but was then promoted to the permanent rank of major in the Regular Army on July 1, 1920. On August 14, 1920, Andrews was sent to Germany to serve with the American Army of Occupation. There he first became Air Service Officer of the American Forces in Germany. Then in June 1922, he became Assistant to the Officer in Charge of Civil Affairs in the Headquarters of the American Forces at Coblentz, Germany.

After returning to the U.S. in February 1923, Andrews served in the Office of the Chief of the Air Service in Washington, D.C. and supervised the Training and War Plans Divisions. Then in June 1923, he became Executive Officer at Kelly Field at San Antonio, Texas. In July 1925, he became Assistant Commandant of Kelly, in command of the 10th School Group at the Air Service Advanced Flying School there. On June 30, 1926, he became Commandant of the School. In September 1927, Andrews entered the Air Corps Tactical School at Langley Field in Virginia. Upon graduation in June 1928, he remained at Langley, where he served with the 2nd Wing Headquarters until July 16, 1928. He then attended the Command and General Staff School at Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas. After graduation in June 1929, he was assigned to duty in the Office of the Chief of the Air Corps in Washington, D.C. There he was promoted to lieutenant colonel on January 13, 1930. He served in this office until August 15, 1932, when he entered the Army War College in Washington, D.C. On October 10, 1934, he returned to duty with the War Department general staff and served its Operations and Training Branch.

This was a very important period in his career for he participated in the reorganization of the Army Air Corps and in the planning for the establishment of the Army General Headquarters Air Force. This was a turning point for the Air Corps, for the GHQ Air Force within the Army was an operating air arm. He was named the Acting Commanding Officer of the GHQ Air Force until February 28, 1935. Then on March 1, 1935 he became its Commanding General when he was appointed to the temporary rank of Brigadier General, being selected over 12 senior colonels and lieutenant colonels. He established the headquarters of the new independent strategic striking force at Langley Field in Virginia. As the first commander of the GHQ Air Force, Andrews was also the organizer of that command and he selected the most energetic of the airpower enthusiasts in uniform for his staff. They were dedicated and purposeful airmen who believed in developing the capabilities of large bombers and were willing to put up with the frustrations of their mission.

The new organization was the first American approach to independent air operations. By the creation of this new organization, the Army Air Corps was taken away from the scattered control of nine Corps Area commanders and concentrated under one head, making it a highly centralized combat unit, as had been recommended by the famous Baker Board the year before. Theoretically, Andrews command was a concentrated striking force of all types of military aircraft. Before, the tactical units of the Air Corps had been scattered all over the U.S. under many general officers and no plans existed for this mass employment. Andrews welded these dispersed squadrons into small but efficient fighting forces of three wings: the Atlantic Wing based at headquarters at Langley Field in Virginia; the Pacific Wing at Hamilton Field in California; and the Southern Wing at Fort Crockett in Texas. Later this Southern Wing was moved to Barksdale Field in Louisiana. He trained this striking force to concentrate rapidly on various airfields along the vast perimeter of the continental U.S. At first, secret mass flights were conducted across the continent. In later maneuvers, bombardment aviation ranged far out to sea to intercept simulated enemy task forces. All of this brought questions from the press, but they found no sensationalism in Andrews’ sober modesty. He said “We must realize that in common with the mobilization of the Air Force in this area, the ground arms of the Army would also be assembling, prepared to take a major role in repelling the enemy — I want to ask that you do not accuse of trying to win a war alone.”

On December 26, 1935, Andrews was promoted to the temporary rank of major general. For the next four years, he continuously studied how to improve the GHQ Air Force and how to make it a striking force that could be ordered to any point in the world for effective action. By now he had become an ardent supporter of the big bomber. He also personally helped to demonstrate their utility on August 24, 1935, when he piloted a Martin B-12 seaplane with 1,202.3 and 2,204.6 pound payloads to new 1,000 kilometer closed-course records. He also had a zest for flight in rain, storm and fog and made hundreds of instrumental flights and landings to prove their practicality under such conditions. On June 29, 1936 Andrews and Major John Whitely and their crew established an international airline distance record for amphibians by flying a Douglas YOA-5 amphibian powered by two Wright Cyclone 800 horsepower engines from San Juan, Puerto Rico to Langley Field, Virginia, a distance of 1,430 miles, which was officially recognized by the National Aeronautic Association and the Federation Aeronautique Internationale.

When urged to give up flying after this he said “I don’t want to be one of those generals who die in bed.” In April 1937, Andrews was rated as a command pilot and combat observer. By now he had become an ardent support of the new long-range, four-engine Boeing YB-17A Flying Fortress bomber, the first of which had been delivered to the 2nd Bombardment Group at Langley Field on March 1, 1937. On October 9, 1937, he pleaded for more and bigger bombers and said “Air attacks cannot be stopped by any means now known. The main reliance to defeat an enemy air force must be bombardment aviation directed against his bases and airplanes on the ground. The airpower of a nation is what is actually in the air today; that which is on the drawing board—cannot become its airpower until five years from now, — too late for tomorrow’s employment.” Andrews was always eager to take advantage of any war game to give tactical training to his bombardment units. These were exercises with aircraft bombing land targets and then targets towed by naval vessels. He used every other opportunity to demonstrate the capabilities of big bombers. One demonstration of the B-17’s capabilities came on February 27, 1938 when six from the 2nd bombardment group, led by Colonel Robert Olds, made a 5,225 mile Goodwill Flight from Miami, Florida to Buenos Aires, Argentina with a stop en route to Lima, Peru. They then returned to Langley Field, Virginia. The first leg of the trip was the longest Air Corps mass flight to date and took 33-1/2 hours. The return flight took 33-3/4 hours. Then in August, 1938, the first B-15 bomber, powered by four 1,000 horsepower engines was delivered to the 2nd Bombardment Group. Later, one made history by flying from Langley Field to Chile in 29 hours 53 minutes carrying 3,250 pounds of medical supplies aboard for earthquake victims.

With the clouds of war darkening over Europe, Andrews fought very hard for a stronger American Air Force, particularly one fully equipped with heavy bombers. On January 16, 1939, he told members of the National Aeronautic Association at their annual convention in St. Louis that the U.S. was a fifth or sixth rate air power. Though more tactful than his hero Billy Mitchell, he was also equally persistent and told a supposedly secret session of the House of Representatives “To ensure against air attacks being launched from any of these bases (in the Caribbean and in South America)—they must be kept under constant surveillance—and we must be ready to bomb such installations as they are discovered. If the situation is sufficiently vital to require it, we must be prepared to seize these outlying bases to prevent their development by the enemy as bases of operation against us.” This statement found its way into the press and Andrews was publicly censured by the President of the U.S. who said that these views were “not those of the White House or the nation.”

Five years later, such a statement would be viewed as one required by “Hemisphere Defense.” However, his endorsement of such a policy did not please most of the members of the Army General Staff, who still believed that Army aviation should be nothing more than “the eyes of the artillery.” Consequently, when his tour as commander of the GHQ Air Force ended in March 1939, he was reverted to his permanent rank of colonel and was ordered to Ft. Sam Houston, Texas as Air Officer of the Eighth Corps Area, — the same post that his mentor, Colonel Billy Mitchell, had been exiled ten years before. Fortunately, Andrews had important friends who believed in him, his abilities, and the scope of his knowledge and the breadth of his experiences. He had previously taken General George C. Marshall on a tour of aircraft plants and the three bases of the GHQ Air Force and had succeeded in winning him over as a new ally for the cause of airpower. Consequently, when General Marshall was appointed as Chief of Staff of the Army, he selected Andrews to serve the War Department General Staff in Washington, D.C. as Assistant Chief of Staff for Operations and Training (G-3). He also promoted him to the permanent rank of Brigadier General in the regular army on July 1, 1939.

He thus became the first airman to handle the Regular Army’s organization and training programs. Marshall’s choice was based on the knowledge that Andrews was not only a distinguished military aviator, but that he was also highly skilled in interservice and international relations. In addition, he was fully versed in the classic management of ground warfare, and the only American officer with experience in the command of a balanced and integrated air arm. In Andrews he saw the emergence of a new kind of Army leader in American History, — one with a knowledge of airpower at the command level and a depth of general staff experience, — qualities not then common among ground or air officers. In October 1940, he was promoted to the temporary rank of major general. After the outbreak of World War II in Europe in September 1939, the importance of the Panama Canal connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and the entire Caribbean area and their adequate defense became a matter of great concern to the War Department.

Among the measures taken to strengthen the defenses in this area was the appointment by President Roosevelt of Andrews as Commander of Panama Air Force on November 14, 1940. On September 19, 1941, he was placed in charge of the Caribbean Defense Command and the Panama Canal Department and elevated to the rank of lieutenant general. As such, he was the first Army Air Corps officer to head a joint command and to hold a major Army Area command. There he was responsible for defending an area extending from his Canal Zone headquarters to Trinidad, and to Brazil and Ecuador. One of his greatest tasks was to insure effective coordination of Navy, Army, Air Corps and Latin American forces. He organized the Air Force of the Caribbean Defense Command on a theater-wide basis and divided into bomber, interceptor and service commands. His chief activity became anti-submarine warfare from the air. He also commanded anti-aircraft defenses, land-based infantry units, and essential Army engineer units at score of jungle bases. The Caribbean Defense Command was unique in that it possessed airborne forces on December 7, 1941, the “Day of Infamy,” when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and the U.S. entered World War II. In 1942, he received the Distinguished Service Medal with the following citation: “For exceptionally meritorious services to the Government in positions of great responsibility as Commander of the Panama Canal Air Force from November 14, 1940 to September 19, 1941. His wide experience in the Army Air Forces enabled him to supervise and coordinate the numerous complicated factors involved in providing and maintaining air equipment and trained organizations available for combat operations.

Through intimate knowledge and by inspirational leadership, sound judgment and devotion to duty, General Andrews created a strong tactical air command vital to the security of the Panama Canal. As Commanding General, Caribbean Defense Command, from Sept. 20, 1941, to November 9, 1942, he rendered services to the Government of outstanding character.” Andrews was also awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross in December 1942 with the following citation: “Frank M. Andrews, lieutenant general, U.S. Army. For extraordinary achievement while participating in aerial flights in furtherance of the development and expansion program of the Army Air Forces.

Since November 1940, as Senior Air Officer and Commanding General of the Caribbean Defense Command, a position of great responsibility, he participated in numerous aerial flights throughout the area of his command in order to supervise personally the establishment of air bases and other defense installation therein. General Andrews, by frequent flights both day and night over water in all kinds of weather, and using airplanes available even though not always best suited for the mission, demonstrated to the flying personnel of his command the practicability of an effective air patrol over the extensive are for which he was responsible. By precept and example in important, difficult and often hazardous flying duties, General Andrews established an effective air patrol which has proven its effectiveness in operations against the enemy. His willingness to lead the way created for the air command under his jurisdiction, a spirit of confidence, loyalty and enthusiasm.

Shortly after the Allies invaded North Africa under Operation TORCH, Andrews was picked by President Roosevelt, General Marshall and General Hap Arnold to become Commander of U.S. Forces in the Middle East. Five days later, he flew to Cairo, Egypt, where he established his command headquarters. There he gained experience in actual combat operations and in working with America’s allies. Under his skillful command, the U.S. Ninth Air Force played a vital part in the Allied offensive, carrying out with conspicuous success the bombing of enemy-held ports and other targets, and destroying numerous fighter aircraft. As a result, the British Eighth Army was able to drive Axis Power forces under the command of German General Rommel back from El Alemein on the Egyptian border and send them on a disastrous retreat toward Tunis.

Andrews also represented his command at the conferences between President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill at Casablanca in January, 1943, where it was decided to establish a European Theater of Operations as a prelude to the later invasion of Europe. When the combined British and American heavy bomber offensive against Germany was approved at Casablanca, General Marshall selected Andrews as Commanding General of the U.S. forces in the European theater of operations with headquarters in London. In this capacity, Andrews’ primary objective was to “increase and intensify the bombing of the enemy.” His outstanding knowledge of every phase of airpower was an invaluable asset to the Allies in the early stages of planning and executing the combined British and American “round-the-clock” bombing offensive against Germany. His base in England was soon described as “one long runway for daylight bomber attacks on Germany.” He also prodded the development of jettisonable fuel tanks to enable Allied fighters to penetrate deeper into Germany while escorting the heavy bombers.

In March 1943, Andrews and Major General Ira C. Eaker, commander of the Eighth Air Force in Britain, received the personal congratulations of Prime Minister Churchill after a successful American bombing raid on the German submarine yards at Vegesack. Andrews, one of the most promising Army Air Force leaders, was killed in an airplane accident in Iceland on May 3, 1943, while on an inspection trip there from England. His plane crashed into a lonely point of land in a very dense fog while trying to find its way to Reykjavik, killing all Andrews and 13 others, with only the tail gunner surviving. Of Andrews’ untimely death, Army Chief of Staff General Marshall said “…the loss to the nation of an outstanding soldier.” He also called Andrews “a great leader” and added that “no army produces more than a few great captains. General Andrews was undoubtedly one of these and we mourn his death.” General Andrews was awarded an Oak Leaf cluster for his Distinguished Service Medal, posthumously, in July 1943, with the following citation: “For exceptionally meritorious service to the Government in a position of great responsibility. As Commanding General of the European Theater of Operations, General Andrews successfully met and solved many complex problems. His calm judgment, courage, resourcefulness and superior leadership have been an inspiration to the Armed Forces and of great value to his country.”

Only 59 at the time of his death, Andrews was rated as a command pilot and had acquired 5,800 hours of flying, only 173 of which were flown as an observer. His other decorations included Commander of the Crown of Italy, Cruz Peruna de Aviacion of Peru, Order of the Sun of Peru, Army Occupation of Germany Medal, Order of Boyaca of Columbia (Grand Officer), Presidential Medal of Merit of Nicaragua, Order of Vasco Nunez de Balboa of Panama, El Sol del Peru (Grand Officer), and the Emblem of the Ejercito Argentino. Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland, nine miles outside of Washington, D.C. was named in General Andrews’ honor on March 31, 1949. It stands as a living memorial to one of the greatest pioneers of the modern U.S. Air Force. Then on April 2, 1954, the Andrews Engineering Building was dedicated in his honor at the Air Force Armament Center at Elgin Air Force Base in Florida.

Andrews Air Force Base is named for Army Lt. Gen. Frank M. Andrews, one of the founding fathers of the United States Air Force.

In February 1943, as wartime Commander of the U.S. European Theater of Operations, General Andrews launched the American strategic air campaign against Germany . When he was killed in an air crash along the Icelandic coast,

three months later, he had the central role in directing operations intended to achieve victory in Europe.

His significance, however, does not depend on what “might have been.” Instead, it rests on the unique contributions he actually made in his lifetime, preparing the Army’s prewar air combat forces for war, and later demonstrating how air forces should be employed within wartime joint theater commands.

Born at Nashville in 1884, he was commissioned in 1906 at West Point, serving in the Cavalry at home and overseas until 1917 when he transferred to Signal Corps aviation during World War I. He earned his pilot wings in 1918, then filled a variety of Air Service and Air Corps staff and command billets, plus assignments in the War Department General Staff. He graduated from the Air Corps Tactical School in 1928, the Army Command and General Staff School in 1929, and the Army War College in 1933.

In fall 1934, Lieutenant Colonel Andrews was commander of the historic 1st Pursuit Group at Selfridge Field, Michigan, when he was detached for special duty in the War Department General Staff, to work on a plan to consolidate for the first time nationwide command over all Air Corps combat units–bombardment, attack, and pursuit — by a single air officer, reporting in wartime directly to Army General Headquarters, or GHQ. Afterward, he was selected to be the first Commanding General of that “GHQ Air Force.”

The establishment of GHQ Air Force at Langley Field, Va., on March 1, 1935 , was recognized as a major milestone in the strategic development of American air power. During four pivotal years at the helm, General Andrews orchestrated sweeping changes to the employment of air combat units, creating the conceptual and material foundations for a modern Air Force. When he introduced the long-range B-17 Flying Fortress into operational service at Langley Field in 1937, GHQ Air Force became the peacetime battle lab for defining the role American air power would play in global war. His GHQ Air Force was the first major step in the evolution of the Army air arm into the postwar United States Air Force.

In summer 1939, only weeks before war erupted in Europe , General Andrews was called to Washington to be Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3. As the Army’s chief of Operations and Training, he was the first airman to head a War Department General Staff Division. In fall 1940, he was reassigned to the Canal Zone to organize the air defense of the Panama Canal , creating the first overseas combat air force. In fall 1941, when he was placed in charge of the Caribbean Defense Command, General Andrews became the first airman to lead a joint forces war-fighting command in an overseas theater of operations. His Caribbean Defense Command became the model for later overseas theater commands.

After Pearl Harbor, when the new Army Air Forces (AAF) gained virtual autonomy within the War Department, that advance owed much to General Andrews’ efforts in changing War Department attitudes concerning employment of air power, going back to his Langley years and continuing later in Washington.

In fall 1942, General Andrews was assigned to Cairo as commander of all US Forces in the Middle East, establishing Ninth Air Force during his tenure there. Early in 1943, he was placed in overall command of the U.S. European Theater of Operations. From his headquarters in London , he directed both the American air campaign against Germany and the planning for the ground forces’ invasion of Western Europe . It was his last assignment. His death in a B-24 Liberator on May 3, 1943 was an enormous loss.

In 1945, less than three month before victory in Europe, Camp Springs Army Air Base, Maryland, was renamed Andrews Field. In 1946, the numbered air forces, whose roots went back to GHQ Air Force, formed the core of the AAF’s Strategic Air, Tactical Air, and Air Defense Commands, reflecting GHQ Air Force’s bombardment, attack, and pursuit missions. When a separate Air Force was established in 1947, the statutory functions of General Andrews’ prewar GHQ Air Force were specifically transferred to the Air Force Chief of Staff. That transfer symbolized his legacy to the new Air Force he did not live to see.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard