NEWS RELEASE from the United States Department of Defense

No. 238-05

IMMEDIATE RELEASE

March 08, 2005

DoD Identifies Army Casualties

The Department of Defense announced today the death of four soldiers who were supporting Operation Iraqi Freedom. They died on March 4, 2005, in Ar Ramadi, Iraq when an improvised explosive device detonated near their patrol. The four soldiers were assigned to the 1st Infantry Battalion, 9th Infantry Regiment, 2nd Brigade Combat Team, Fort Carson, Colorado.

The soldiers are:

Captain Sean Grimes, 31, of Southfield, Michigan

Sergeant First Class Donald W. Eacho, 38, of Black Creek, Wisconsin

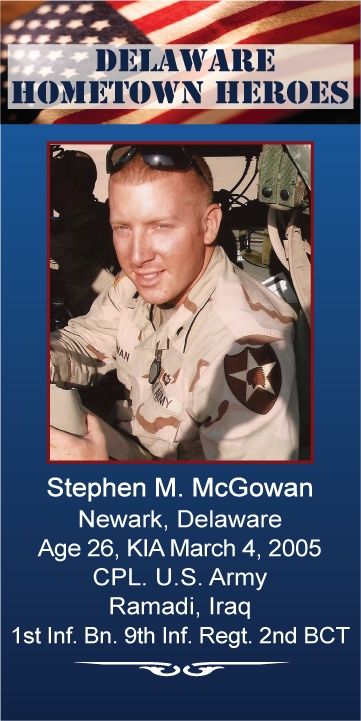

Corporal Stephen M. McGowan, 26, of Newark, Delaware

Specialist Wade Michael Twyman, 27, of Vista, California

The family of an American soldier killed in Iraq mourned his loss and celebrated his life Sunday night.

Corporal Stephen M. McGowan, 26, of Newark, Delaware, died March 4, 2005, in Ar Ramadi, Iraq, when his vehicle struck a roadside bomb, according to information provided by the Department of Defense.

McGowan’s paternal grandmother and extended family live in Delaware County. His father, Fran DiDomenicis, said he last communicated with his son two days before his death. It was an e-mail, and it was good news.

“We had just gotten word that he would be coming home for Easter,” DiDomenicis said. “And we were looking forward to that.”

It was the last time the two would communicate.

McGowan was a combat medic who served with a scout platoon, a position that was a “very high honor,” his father said. McGowan had volunteered for combat duty, and always had a “sense of justice.

“He was always a physical guy, but he always had that sense of protecting others, of justice, of enforcing the rules,” DiDomenicis said through tears. “He was very well loved.”

On the Web site fallenheroesmemorial.com, a site dedicated to soldiers killed in Iraq, people who didn’t know McGowan posted their thanks for his sacrifice, and those who knew him shared their grief.

One posting, which seemed to validate what everyone said of McGowan, was written by Robin Lynn Williams of Philadelphia. Williams left for basic training the same day as McGowan, and sat next to him on the plane.

“When he noticed how scared I was, he was nice enough to take the pillow out from under his own head and give it to me,” Williams wrote. “He gave me his blanket, too. He didn’t even know me ..He was trying to help me be more comfortable so I wasn’t so scared.”

Family and friends gathered at Corpus Christi Roman Catholic Church in Elsmere, Delaware, for a closed-casket viewing Sunday night.

McGowan is also survived by his mother, Bobbie McGowan, and a sister, Michaela McGowan, a senior at Cabrini College. They both live in Delaware.

McGowan had served with the 1st Infantry Battalion, 9th Infantry Regiment, 2nd Brigade Combat Team, since August. Before that, he served 15 months in South Korea. Three of his fellow soldiers were also killed in the March 4 explosion.

After high school, McGowan studied criminal justice at the University of Delaware and Wilmington College. He considered becoming a police officer, but decided he would not like certain aspects of the job.

“I think he thought police work would be too routine at times,” his father said.

McGowan played in a rugby league and enjoyed going caving with his father.

DiDomenicis is an expert in dealing with grief and loss, but he usually deals with it from a greater distance. A psychologist in Wilmington, DiDomenicis specializes in helping people deal with their own emotions when tragedy strikes. Now, the tragedy has struck his own life. He said his training, education and experience are helping.

“Sitting compassionately with others expands the heart, and helps the help-givers get through their own tough times,” he said.

McGowan’s funeral will take place at 10:30 a.m. today at Corpus Christi Church. On Tuesday, his remains will be buried in Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors.

22 May 2006:

He needed to get to Bobbie. He needed to be with her. The priest rushed to the mother the moment he found out. Corporal Stephen McGowan, 26, had been killed the day before by a bomb in Iraq.

As he drove, Father Greg Corrigan prayed the rosary to clear his head.

The explosion. The charred vehicle. The broken body of his friend.

Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee…Pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death.

Father Greg had known Stephen since he was a curly-haired boy with a cherubic smile and a devilish wit. He had watched with pride and fear as Stephen grew up to become a burly Army medic who liked to drink beer and play rugby but had a gentle heart.

The priest loved this family — Stephen and his younger sister, Michaela, and their mom, Bobbie, who doted on her son. He counseled them when Bobbie and her husband divorced a decade ago. He prayed publicly for Stephen every Sunday at Mass.

At Bobbie’s side, the priest embraced her.

“How could God take Stephen?” she sobbed.

Father Greg wept.

“God didn’t take Stephen,” he said, looking into her eyes. “A war took Stephen. Evil in the world took Stephen. God caught him when he fell.”

He said it again. And again. And again.

God didn’t take Stephen. A war took Stephen.

It became her mantra, the holy cadence that helped her walk through dark days, first at Dover Air Force Base on March 7, 2005, when an honor guard carried the coffin carefully from the mammoth C-5 aircraft, its engine rumbling like a drum roll as soldiers gave slow salutes.

Bobbie McGowan stood crying on the tarmac with her family and the priest.

“I am so proud to be his mother,” she said.

Then at the funeral home, where an Army captain had told her the casket must stay closed, where she signed a paper allowing the Army to cremate any additional parts of her son they found. She stopped the conversation every few minutes to throw up.

God didn’t take Stephen.

Then at the viewing — where for five-and-a-half hours she greeted hundreds of people who lined up to pay respects, where she asked the priest for a few minutes alone with her son so she could hug the closed coffin and say goodbye.

Then at the funeral, where Father Greg tried to comfort those with questions.

A war took Stephen.

Father Greg doesn’t believe in war — this war or any war.

He is an unrepentant bleeding heart who takes blankets and peanut butter and jelly sandwiches to the homeless in Philadelphia every winter. He begged Stephen not to join the Army, just as he has begged countless other youths at St. Mark’s High School over the last 17 years.

But Stephen — a confident 22-year-old powerhouse of a man — felt certain of his path. Smiling, he reassured the priest.

“Father,” Stephen said, “you worry too much.”

Those were the same words he said to his mother when he e-mailed from Iraq. “Mom: I love you and I’m OK,” he wrote after describing a bloody firefight in Ramadi last fall. “In the middle of all that I had a moment where I looked at my watch and it was on East Coast time. It was 10:30 on a Sunday morning. So I knew you were probably at church praying for me. Good job.”

At his funeral, she wore a blue suit, white stockings and a swatch of red ribbon on her lapel.

More than 500 people filled the pews at Corpus Christi Catholic Church in Elsmere. In his sermon, Father Greg shared Stephen’s one regret: When he was at the airport, leaving for Kuwait, he didn’t give his mother “one more hug” before walking away.

“Now we must embrace each other for him,” the priest said. “We must love one another, reach out to those who are hurting. We must be his arms and his heart in a world that is so hurting, so much in need of ‘one more hug.'”

At Arlington National Cemetery, tourists paused as the funeral procession approached. Men removed their hats. Women touched their hearts.

Bobbie McGowan cherished those gestures. They cushioned the jagged edges of the words the Army messengers used: Catastrophic. Instantaneous. Unviewable.

In those moments, when her heart began to pound and her breath began to race and she started to sink under the weight of the loss, she did what the priest told her: Go back to what you know is real.

Go back to when you held him as a baby, Father Greg said. Go back to how that felt.

How when you took him for his first shot you cried so hard the doctor said: Don’t ever drive to the hospital alone again.

How Stephen — he couldn’t have been more than 6 — stood one night in his pajamas, his blue eyes wide and wondering.

“Mom, how do you know I’m here?” he said. “And how do you know you’re here? How do you know I’m not dreaming you and you’re not dreaming me?”

The young mother caught her breath, stunned by the depth of the child’s thoughts.

“Because of how much I love you,” she said.

God didn’t take Stephen. A war took Stephen.

On a cool March day, with sunlight piercing the clouds, Father Greg held his right hand over Stephen’s coffin and said a final prayer.

Bobbie McGowan wrapped herself in the warmth of family and friends and in the security of military tradition: The crack of the rifles. The solemn salutes. The folded flag.

She cradled it against her heart as the honor guard marched away.

28 May 2006:

This is the beginning of forever.

A quiet cemetery.

A cold stone.

A long walk down a hallway toward a mother’s door.

In her mind, Bobbie McGowan still sees them, the man and the woman in pressed Army uniforms, their grim faces telling her what her heart already knew.

Oh no, oh no, oh no, oh no.

“Steve McGowan,” she sobbed, before they were halfway down the hall. “Stephen McGowan. Are you sure? Are you sure?”

“Yes ma’am,” the man said. “We’re sure.”

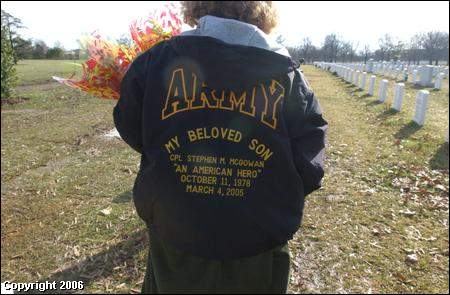

A year later, she knelt at her son’s Arlington grave and wept, the mournful sounds coming from some deep place untouched by time.

Every day, she replays the moment in her mind, as though somehow she might alter the ending. Then her son, Cpl. Stephen McGowan — big brother, beer drinker, rugby player, philosophy reader, world traveler, mountain climber, soul searcher, statistic — would emerge from the bomb-blasted Humvee unscathed and come home from this war.

He would walk in the door, give her a hug, kick back and talk about what it all means.

The soldiers stood at a distance, watching the mother grieve. They came from as far away as Utah to honor Stephen – the medic they called “Big Mac.” The 26-year-old died exactly a year ago on March 4, 2005, near Ramadi, Iraq.

They came to help Mac’s mom, to tell war stories and give her another chance to be a soldier’s mother.

“I can’t believe he came without a jacket,” Bobbie McGowan said, spotting Dan Watson at the entrance of the cemetery. The 23-year-old former Army scout was the first to get to Stephen after the bomb exploded, the first to know there was no chance he could survive.

Just out of the Army, Watson wore baggy jeans and a long-sleeved shirt, his hands stuffed in his pockets, shoulders hunched against the freezing wind.

“Every ounce of the mother in me wants to smack him,” she said.

They came, too, because they never really got to say goodbye. In Iraq, the platoon was given two days off to grieve. Then they went back to war.

At the cemetery, they gathered in silence with Bobbie’s family and friends in a circle at the foot of Stephen’s grave.

“Stephen, he loved life,” Bobbie said. “He loved you.”

After a prayer, the soldiers wandered among the headstones, looking for other friends.

Family members stood in small groups, talking quietly.

Bobbie McGowan’s great-nephews played in the grass nearby, their red, white and blue pinwheels spinning in the wind.

Only the mother was alone – kneeling in the mud, bent over the grave, hugging the tombstone, overcome.

A few hours later, Bobbie McGowan’s sad eyes sparkled, and her laughter bounced around the dining room of her sister’s home near Arlington. She listened to the stories of the scouts.

Jason Hagan had just finished a gut-buster about Mac.

Some soldiers were on patrol near Ramadi when fighting broke out.

“We ripped this guy off the motorcycle because he’s not stopping for us,” Hagan said. “Soon as we did, Mac got him spread out. Mac’s pattin’ him down and searching and reaches in his pockets. … This guy had half a dozen eggs in his pockets, you know, going home for dinner. Mac reaches in his pockets and pulls out egg yolks!”

The room erupted with guffaws.

These were the young, strong men who loved her son but could not save him. With only a few days’ leave, three of them had driven more than 1,500 miles from Fort Carson, Colo. It took almost 30 hours.

Jacob Keiffer, Brent Short and John Pushard – all still in the Army – had piled into a car and taken turns driving. They pulled over at a rest stop outside Arlington to put on their dress uniforms. Later, they stopped by the house to eat ham sandwiches and change back into civilian clothes for the long drive home.

Bobbie rubbed Keiffer’s shoulders, like a mother would. He had a headache from too much sadness and too little sleep.

“I can’t believe how much that hurts,” said Keiffer, 22. His red hair reminded her of Stephen’s.

Home from Iraq for eight months now, he had struggled to come to terms with Stephen’s death. Moments before the explosion, he’d felt uneasy. He had turned to a soldier in his Humvee and said: “Watch out for wires.”

He wondered why Stephen had died and he had lived.

His eyes looked almost old as he remembered his friend. With three more years to serve, Keiffer almost certainly would return to war.

“I respect life a lot more,” he said. “I have a much greater knowledge of the time we actually have, knowing that in a matter of seconds … that can be taken away.”

The war had changed Stephen, too. Even from across the world, Bobbie could tell. He would have been home on leave in three weeks. All he wanted to do, he told her, was take a hot shower, go to the grocery store and spend time with friends.

“No big parties, Mom,” Stephen had said. “Don’t make a fuss.”

She’d planned a party, anyway, one they never had.

Losing Stephen almost crushed her, but she struggled to go on.

“I get up every morning and say, ‘OK, Stephen, I’m going to try and be as courageous as you were. … I’m going to try to love life like you did. I’m going to try to live like you did.’ ”

In rare moments, she can imagine looking at her son’s photo and feeling only joy.

She is not there yet – not even close.

Postscript: On Tuesday around 9 p.m., Bobbie McGowan received a phone call from an Army representative notifying her more of Stephen’s remains had been identified through DNA testing at Dover Air Force Base. Bobbie plans to have a short memorial service and bury these remains at Arlington.

Family returns to Arlington. At a second service, Army corporal’s loved ones relive their loss

Corporal Stephen McGowan’s name wasn’t on the list of 45 funerals scheduled at Arlington National Cemetery.

His family buried him almost 15 months ago, after he was killed by a bomb in Iraq.

So when a white stretch limousine carrying a dozen of Stephen’s loved ones pulled into the cemetery’s gates Tuesday afternoon for a memorial service, security guards at first didn’t understand.

Stephen’s mother, Bobbie McGowan of Newark, Delaware, calmly explained it to one employee. Inside the cemetery’s administration building, she explained it to someone else.

“They found another piece of him,” said McGowan, 56, who buried her son at Arlington on March 15, 2005. “It was his leg. I know that sounds awful. They buried it earlier today. We’re here to do a memorial service.”

Security flagged the limo through to Section 60, No. 8104, where the earth at the bottom of Stephen’s grave was freshly turned.

Hours earlier, a cemetery work crew had dug a new hole and buried a small wooden coffin, designed to hold an infant.

Inside was one more precious piece of Bobbie McGowan’s only son.

The remains, held at Dover Air Force Base’s Charles C. Carson Center for Mortuary Affairs for more than a year, were determined to be Stephen’s only recently through DNA testing, an Army captain told Bobbie.

Capt. Jason Blanton, 32, the Aberdeen, Md.-based casualty assistance officer who last year helped Bobbie plan Stephen’s funeral and sort through his personal effects, gave her the news by telephone the night of May 23.

It was unclear why the identification took so long.

Nearly 2,500 U.S. military men and women have been killed in Iraq since fighting began in 2003, according to the Department of Defense.

More than 35 percent — or 881 as of Wednesday — have been killed by roadside bombs, known as improvised explosive devices, according to data on icasualties.org, an independent tracking source.

All remains are sent to Dover, where the military operates its only stateside mortuary. There, remains are first scanned for unexploded ordinance, identified through X-rays and dental records, then prepared for burial.

The process usually takes about 72 hours, Karen Giles, director, said. If DNA identification is necessary, it can take a day or two longer.

As was the case with Stephen, many of the bodies are so badly damaged the Army recommends families don’t open caskets — even to say goodbye.

‘We bring together’

Tuesday morning, Stephen’s family was not allowed to be present when the new grave was dug.

Bobbie’s priest, the Rev. Greg Corrigan, stood at the grave that afternoon and prayed. He encouraged family and friends to remember Stephen’s laughter and love.

“In remembering, we bring together,” said Corrigan, pastor of Corpus Christi Church in Elsmere. “The separate pieces become one.”

A St. Mark’s High School graduate, Stephen, 26, had almost completed a reconnaissance mission with his platoon near Ramadi when a roadside bomb destroyed his Humvee on March 4, 2005. Three other soldiers died with him that day.

For Bobbie, the new grave brought new grief.

Though she wore red, white and blue to her son’s first burial at Arlington to honor his love of America and life, this second time she wore black.

“It feels more like that for me today,” she said on the way to Arlington, while sharing stories and memories with family and friends. “Today I feel very sad. … It’s a harsh reminder of how badly Stephen was hurt.”

Stephen’s sister, Michaela McGowan, 23, held out a cell phone during the short memorial service so Stephen’s Army friend, Jason Hagan, could hear from his home near Grand Rapids, Mich.

Hagan, 25, put Stephen into a body bag after fellow soldiers pulled his remains out of a pond the day he died.

On the year anniversary of Stephen’s death in March, Hagan came to Arlington with about a dozen other Army buddies.

Now out of the Army, Hagan calls Bobbie every Sunday. He told her a few more details about Stephen’s death when she called him to tell him the Army had identified additional remains. He comforted her tears.

“Stephen’s been home a long time,” Hagan told Bobbie. “I know this is precious to you. … But Stephen’s been home a long time.”

The Legacy Of The ‘Beanie Baby’ Soldier

Larry Mendte, Courtesy of CBS3

29 December 2006

The numbers that are reported every night on the news of the casualties in Iraq can be cold and impersonal because every number represents a hero, many from our area. And every number is a story that deserves to be told. CBS 3’s Larry Mendte relates the story of Corporal Stephen McGowan – the Beanie Baby soldier.

There are people in this world who can create a ray of hope in our darkest hour of despair.

Stephen McGowan, 26, joined the army in the tsunami of emotion that flooded this country after 9/11.

“For him protecting the nation was an immediate response,” said his mother Bobbie McGowan.

And when it was time for soldiers to go to Iraq, Stephen volunteered.

“His roommate had a 3-year-old and he felt it was his duty to go before men who had children,” said Bobbie.

McGowan made children his mission in Iraq. Even though he was a medic in a scout group that saw action and atrocities almost everyday, he found beauty and hope in the faces of Iraqi children.

“He said don’t send me anything for Christmas this year just send me toys to give to the children,” said Bobbie.

The easiest toys to carry on missions were Beanie Babies. Stephen started handing them out to the Iraqi Children and the story quickly spread of the Beanie Baby soldier.

“We were inundated with Beanie Babies,” explained Bobbie.

The Beanie Baby soldier started getting letters from school children in the United States and he would send back a photo essay he put together to explain to children why our country is in Iraq.

It is still played in classrooms and it still has a powerful impact

“The presentation that we just saw, there are no words for it; is the human soul and its core,” said Adam Pranda of the Cab Calloway High School in Wilmington.

“It just gives us hope that there are people like that willing to die for us and it’s really very touching,” said student Meg Barton.

Especially touching because it is a message from the grave.

In March of 2005, Bobbie broke down when she saw two officers making the long walk down the hall to her Newark apartment.

“I just said no, no are you sure it’s Stephen and he said yes ma’am we’re sure,” said Bobbie.

Stephen McGowan died when a roadside bomb detonated near his patrol near Ramadi. His body is buried at Arlington National Cemetery but he left us all something; hope in its most innocent form.

The Beanie Babies just keep coming in. The Delaware State Police and a charity named after a fallen trooper have picked up where Stephen left off

“To date we collected over 55,000 Beanie Babies, we put hundreds in boxes and send them 50 at a time to Iraq,” said Jennifer Hawkin, co-founder of the Ronald G. Williams Foundation.

Recently members of the Delaware Air National Guard handed out thousands of the beanies during their tour in Iraq.

Woody Gilger was there and remembers a little Iraqi girl who was scared of the soldiers until she saw the Beanie Baby.

“That picture is worth a thousand words. She saw the Beanie Baby and came right up to us and smiled. And then I knew I was doing something worthwhile. It was that type of feeling,” said Gilger.

And imagine how that little girl feels now or any Iraqi Child who goes to bed with the comfort given them from the heart of Stephen McGowan.

“It’s going to be much harder to convince that child that Americans are devils when they have a soft Beanie Baby and they remember that soldier knowing he gave it to them,” said Bobbie.

And that is the gift that Stephen McGowan gave us; the gift of hope for the next generation.

MCGOWAN, STEPHEN MICHAEL

- CPL US ARMY

- DATE OF BIRTH: 10/11/1978

- DATE OF DEATH: 03/04/2005

- BURIED AT: SECTION 60 SITE 8104

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard