Hervey Allen

Born December 8, 1889, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Died December 28, 1949, Coconut Grove, Florida

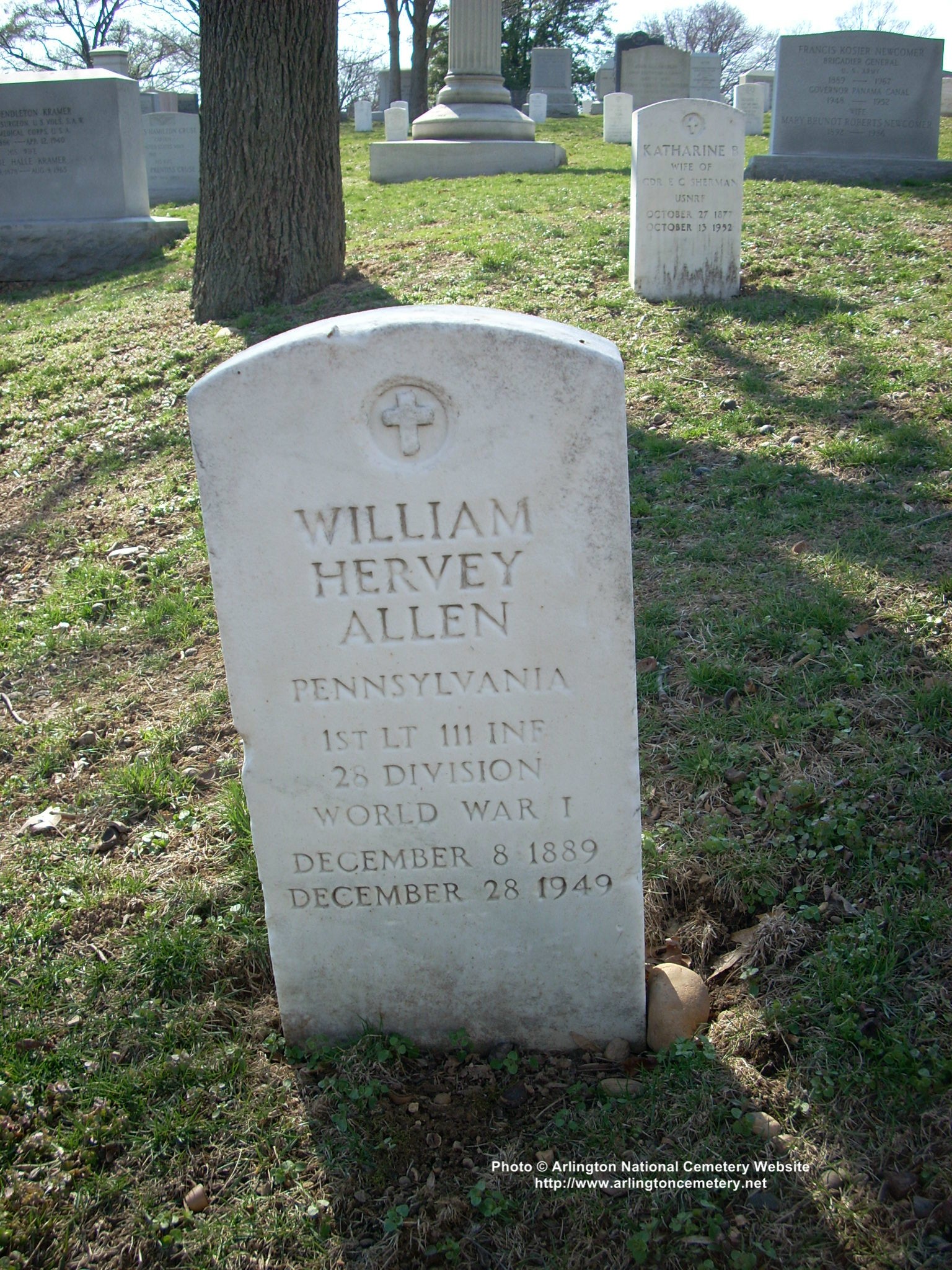

William Hervey Allen, Jr. American poet, biographer, and novelist who had a great impact on popular literature with his historical novel Anthony Adverse.

Allen’s first published work was a book of poetry, Ballads of the Border (1916). During the 1920s he established a reputation as a poet, publishing several more volumes of verse.

Allen was wounded in World War I; the novel Toward the Flame (1926) came out of his wartime experience. That same year his authoritative biography Israfel: The Life and Times of Edgar Allan Poe was published.

In 1933, after five years of writing, he published Anthony Adverse, which was a huge success. Set in Europe during the Napoleonic era, Anthony Adverse offered a multitude of characters and picturesque settings within a complex plot. The book’s undisguised passages about sex and its considerable length introduced a new standard for popular fiction.

Allen’s following novels did not attain the popularity or the critical acclaim of Anthony Adverse, although the first three volumes of his planned five-volume series about colonial America (The Forest and the Fort, 1943; Bedford Village, 1944; Toward the Morning, 1948) were widely read. Allen was at work on the fourth volume of the series (The City in the Dawn; published posthumously, 1950) at the time of his death.

Over the years many authors have written stories about Bedford and Bedford County’s part in the formation of the new country, but few have ever achieved the distinction that has been given to William Hervey Allen Jr. He was rated as one of the seven outstanding authors of Pittsburgh.

Hervey Allen was born in Pittsburgh in 1889 and lived most of his life at 6215 Fifth Avenue. This home was destroyed by a fire a number of years ago. He was graduated from the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Business administration in 1915. He taught school at Porter Military Academy in Charleston, South Carolina, Columbia University and Vassar College.

According to stories told by older residents of Bedford, Hervey Allen came to Bedford with his parents when he was a young man to spend their summer vacations. He came to love Bedford so much that he continued to return to this town every year. He made many friends here whom he never failed to visit or chat for a few hours. One of his closest friends was Clarence ‘Judge’ Davidson, who had a small antique shop located in the corner room of the Pennsylvania Hotel. Through his associations, both as a child and an adult, he came to know much of the history of this community. Two of his heroes in history were Colonel Henry Bouquet and Captain Simeon Ecuyer. In fact, he rated them superior to Forbes, Washington and Braddock in the formation of Pittsburgh and the development and safety of the settlers of western Pennsylvania.

Based on his knowledge of history, Mr. Allen wrote his first book of a series -‘The Forest and the Fort’. Here, he based his story on the exploits of Bouquet and Ecuyer and a fictional character who had been captured by the Indians when he was a child. He followed up his series with ‘Bedford Village’ and ‘Toward the Morning’. These three were combined into one volume called ‘The City in the Dawn’.

Another of Allen’s successful works was ‘Anthony Adverse’. In fact, this was his first successful story. It brought to him fame and fortune. He sold more than three million copies.

Hervey Allen died at Miami, Florida, in 1949. He was in the process of writing another in the series dealing with the early days of Fort Pitt when he died.

Much credit must be given this man, who adopted Bedford as his summer home, for helping to make this community better known historically.

William Hervey Allen, Jr. was a major American novelist of the 1930s and 1940s, specifically for his book Anthony Adverse, one of the biggest selling novels of the 1930s and the source for a massively successful Warner Bros. film. In actual fact, he enjoyed two successful careers as an author, first as one of the most popular poets of the “lost generation” that immediately followed World War I, and then as a bestselling author of historical fiction.

Rather ironically, he’d never set out specifically to be an author, per se, but fell into writing while in search of a career for himself and convalescing from injuries suffered during World War I. Born William Hervey Allen Jr. in Pittsburgh, PA, he was the son of William Hervey Allen Sr., an entrepreneur and inventor, and the former Helen Eby Myers. He grew up very distant emotionally from his father, whom he held responsible for impoverishing the family with his dubious business ideas, and was, instead, an admirer of his paternal grandfather, who had been a pioneer and an engineer. The pioneers, the spirit behind them, and the builders of the American continent, would later become key focuses of his fiction.

Allen qualified for admission to the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis, but he was forced to leave as a result of serious sports injuries. He received a degree in Economics from the University of Pittsburgh in 1915, but in the absence of any serious career goals, he began writing poetry and also seeking out some larger cause in which he could serve a useful purpose. He became a passionate believer in President Woodrow Wilson’s attempt to intervene in the Mexican Revolution on behalf of democratic rule, and this was how Allen came to join the Pennsylvania National Guard in 1916; he served in a unit posted to El Paso for several months before returning to civilian life.

Allen was only back three months when the United States entered World War I, and he was recalled, promoted to First Lieutenant, and posted to France. He might well have not lived through the conflict: Allen served in combat and was gassed, succumbed to shell-shock (what is now called Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder), and spent an extended period in the hospital. It was there that his literary career began, with the poetry he wrote about his war experiences. His work was filled with cruel, bitter imagery and a profound sense of waste, reflecting the author’s own disillusionment. His writings found a wide audience among millions of readers for whom the American involvement in the European war — though it had very likely saved civilization in Europe — was a psychological and social wound that wouldn’t heal.

The Blindman, published in the December 1919 issue of North American Review, became his best known poem; read by millions, widely praised, studied, and discussed, it heralded the perceived birth of the “lost generation” of the 1920s, dislocated from their social moorings, their youth and expectations shattered, and adrift in life. The acclaim for his work hit Allen rather suddenly, and at a point when he was still putting the finishing touches on his skills and credentials as a writer; in 1919 and 1920, as he was becoming a major poet, he was taking graduate courses at Harvard. By the early part of the decade, Allen had gone into retreat from his fame, taking a job as a high school English teacher in Charleston, SC, where he also took a part in founding the Poetry Society of South Carolina.

He later taught at Columbia University and Vassar College — where he subsequently married one of his students, Ann Hyde Andrews — and gradually shifted his work toward prose as well as poetry, publishing a personal remembrance of the war entitled Toward the Flame: A War Diary in 1925, and Israfel: The Life and Times of Edgar Allen Poe the following year.

During the 1930s, Allen gave up writing poetry almost entirely, turning to prose with greater energy and ambition than ever. His most widely read work, the epic novel Anthony Adverse, followed in 1933. One of the biggest bestsellers of the 1930s, its success only surpassed by Gone With the Wind and a tiny handful of other books, Anthony Adverse was a historical novel set during the Napoleonic era, telling of a man’s journey across life and several continents in search of a meaning to his life. In a manner that anticipated the selling of the Harry Potter books and other late-20th century pop-culture phenomenona, Anthony Adverse was among the first American novels to be cross-promoted to the public through product tie-ins and other similar promotional devices. The screen rights were purchased by Warner Bros., which spared no expense in filming this blockbuster, among the most expensive releases by the studio before the 1950s. The studio assigned as producer its most prodigiously talented executive, David O. Selznick, who really broke the ground for his production of Gone With the Wind (which hadn’t even yet been published) with this film; director Mervyn LeRoy turned it into a box-office hit starring Fredric March. The movie also served as a vehicle for one of the most distinguished film scores ever written by Erich Wolfgang Korngold. The novel would prove to be the commercial high point of Allen’s literary career — his subsequent novels all sold very well but never dominated the imagination of the mass public in the way that Anthony Adverse had, and none of his later books were brought to the screen.

As late as 1940, his chronicles and observations of World War I were still commanding serious critical attention and readership — a 1940 publication, It Was Like This: Two Stories of the Great War, was represented in the personal library of Eleanor Roosevelt, wife of the president. Allen’s outlook on the world changed with the times, and in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor, he abandoned his pacifism. He began work on The Disinherited, which was conceived as a pair of historical epics starting in colonial America, dealing with the birth of the United States, telling of the resourcefulness of the people who started the spread of democratic ideals across the continent. He had finished most of the first volume, The City and the Dawn (which included the books The Forest and the Fort, Bedford Village, and Toward the Morning), and they were completed posthumously with sections of a fourth book that rounded out the planned first half of the epic; the second half, Richfield Springs, was never finished. Even as he spent his last years on this massive series of novels, Allen also branched into nonfictional work, as the editor of a series of books called “Rivers of America.” The latter helped popularize an environmental consciousness decades before such notions were widely acknowledged or accepted. This was principally a result of his decision to move his residence to Florida, where he developed a deep love for the Everglades. He kept a residence at the Glades in Dade County, where he worked during the last years of his life. Allen died in his home there at the very end of 1949, just weeks after his 60th birthday. Along with Kenneth Roberts and Ben Ames Williams, Allen was one of the most widely read authors of historical fiction of his generation, and his books were heavily reprinted in paperback long after his death.

POWERFUL FRONTLINE MEMOIR OF WORLD WAR I

Toward the Flame: A Memoir of World War I. Hervey Allen. University of Nebraska Press. 282 pages; drawings; Reviewed by Michael D. Hull

Scion of a prominent Pittsburgh family, Naval Academy dropout and poet William Hervey Allen Jr. was one of the thousands of young Americans in campaign hats, choke collars and leggings who went to France in 1918 to help “make the world safe for democracy.”

Handsome and articulate, Lieutenant Allen had served on the Mexican border in 1916 with the 18th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, but now, in May 1918, he was headed for a real shooting war as a company commander in the 111th Regiment of the 28th Infantry (Keystone) Division, a National Guard outfit and part of the American Expeditionary Forces.

After landing at St.-Nazaire and training with the British and French, Allen’s regiment moved into the Marne sector. There, on July 15, 1918, the Germans launched the second Battle of the Marne, aimed at carrying the war closer to Paris and drawing reserves from Flanders, where the British Expeditionary Force was carrying the brunt of the Western Front fighting.

In his literate, finely crafted memoir, Allen describes with a clear eye and lack of sentiment how the green 111th Regiment was thrown into the middle of the great campaign and received its torturous baptism of fire while trudging — often in a sleep-deprived stupor — from the Marne to the River Vesle.

It was open warfare, bearing little resemblance to the static trench fighting that had characterized the Great War since 1914. Nevertheless, as Allen’s harrowing narrative shows, he and his men advanced across lovely but treacherous landscapes where the next village or cluster of trees might hide German field guns, machine gunners or flame throwers.

By August 5, Allen’s regiment had helped to push the enemy to a new defensive line 20 miles north of Chateau-Thierry.

But Major General Jean Degoutte, the French Army commander under whom the Keystone Division served, wanted more. Working from faulty intelligence and military doctrine, he ordered the capture of Fismette, a village on the German-held northern bank of the Vesle.

Fismette was accessible only by a half-demolished bridge that was under continual enemy artillery and machine-gun fire.

By the time that Allen led his Pennsylvanians across the bridge, it was painfully obvious to everyone except Degoutte that the position was untenable.

The author paints a grim picture of nightmarish house-to-house combat there as German artillery and machine-gun fire poured in from the surrounding hillsides, wounding or killing most of his comrades. Allen lasted in the inferno for four days until, wounded by shrapnel and sickened by mustard gas, he was transported back to a French base hospital.

The village fell to the Huns on August 28. Fismette, writes Allen, was one of the blunders of the 1918 fighting and an example of coalition warfare at its worst.

It was the terrible flame toward which he and his men had marched, and which provides the climactic finale to his memoir. After recovering from his wounds, Allen rejoined his battered unit for the big Aisne-Marne offensive and later served as a translator with the French Army.

Covering a mere six weeks in the summer of 1918, his book is elegant in its simplicity, almost photographic in detail and intensity and devoid of any pretense about patriotism, esprit de corps, or the sense of brotherhood that some soldiers on the Western Front felt toward their foes.

Allen had no illusions about the hellishness of war. Of the enemy, he writes, “I disliked the Germans, but I disliked them because I feared them, knowing full well their deadly capability.”

While he acknowledges the stupidity and callousness that sometimes reigned within the Allied war effort, the author also cites many instances of heroism, fortitude and compassion.

First published in 1926, with stark drawings by Lyle Justis, this work has been considered by many to be the finest American frontline memoir to come out of World War I. It is powerful and certainly a classic.

Allen also published six volumes of poetry, wrote novels about the American Revolution and the Civil War and lectured at Columbia University and Vassar College. He is best remembered for his 1,224-page epic novel about the Napoleonic era, Anthony Adverse, one of the best-selling historical novels of the 20th century.

HERVEY ALLEN RITES HELD

MIAMI, Florida, December 30, 1949 – A funeral service for Hervey Allen, author of “Anthony Adverse,” who died Wednesday at the age of 60, was held today at his home, the Glades. The Rev. W. C. Hanner, rector of St. Stephens’ Protestant Episcopal Church conducted the service.

The body was sent tonight to Arlington, Virginia, where it will be buried with military honors in the National Cemetery.

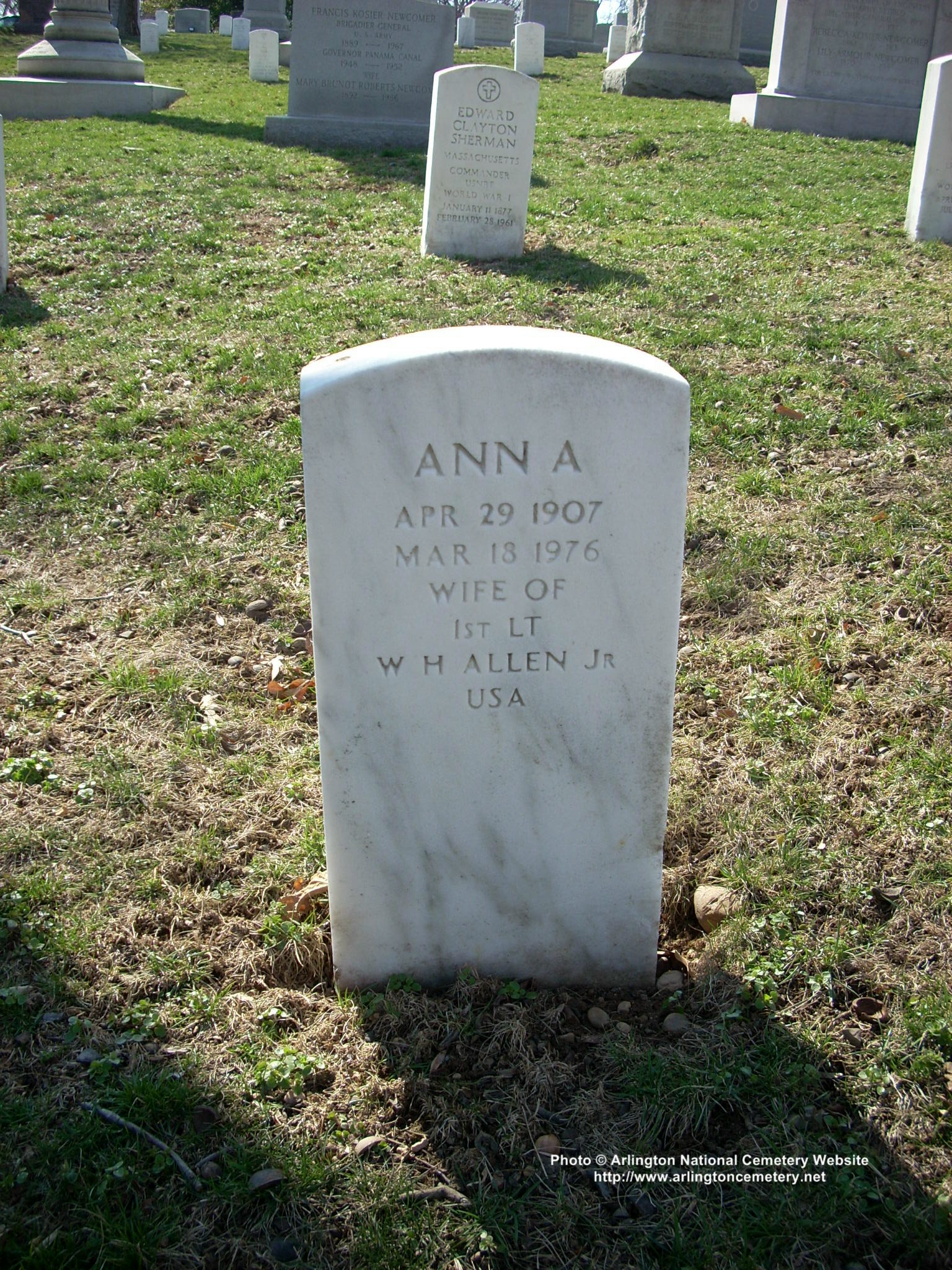

ALLEN, WILLIAM HERVEY JR

- CO. B. 111TH INF. 28

- DATE OF DEATH: 12/28/1949

- BURIED AT: SECTION 3 SITE 1730-C

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard