From contemporary press reports:

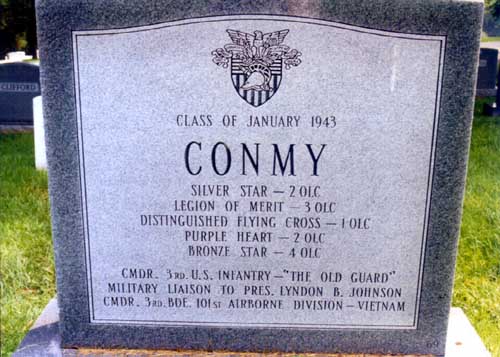

Combat Infantryman’s Badge (3)

Joseph B. Conmy, Jr., a heavily decorated Army infantry Colonel who commanded U.S. troops in a bloody, controversial battle in Vietnam and also served in two other wars, died of cancer April 22, 1994 at his home in Vienna, Virginia.

The son of an Army office, he was born at Fort Snelling, Minnesota. He grew up on various Army posts in the U.S., in the Philippines and on Hawaii when it was a U.S. territory. He graduated from the United States Military Academy in the class of 1943. By the time he retired thirty years later, he had received three awards of the Silver Star for gallantry, five awards of the Bronze Star for valor, two awards of the Distinguished Flying Cross, four awards of the Legion of Merit, and three awards of Purple Heart for wounds he suffered in action. He was one of only 230 Army soldiers to have received the coveted Combat Infantryman Badge in three wars.

In World War II, served as a platoon and company commander in Europe. In the Korean War, commanded a company and then a battalion. Subsequently, was an instructor in tactics at West Point.

He also graduated from the Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and from the Army War College at Carlyle Barracks, Pennsylvania. From 1956 to 1959, served at NATO Headquarters in Paris. In 1960, stationed in Washington, DC as an intelligence officer. In 1962, he took command of Third Infantry at Fort Myer. The Third Infantry, which is called “The Old Guard,” was the unit in which his father was serving when he was born at Fort Snelling.

Later in 1960s, he was a military aide to President Lyndon B. Johnson, and he traveled extensively with the President. In 1968, went to Vietnam to command Third Brigade of the 101st Airborne Division. In May of that year, he led the brigade in the battle of Hamburger Hill in the Ashau Valley, one of the major battles of the war. After several days of desperate fighting, the hill was taken. A week later, brigade repulsed a night assault in the course of which he was wounded.

He returned to the US in 1969. In 1973, he retired from the Army and became a research engineer for several companies. He also was an adviser on the films “Hamburger Hill,” which was about the battle, and “Gardens of Stone,” which was about the Third Infantry and remembering fallen comrades.

The action at Hamburger Hill remains one of the controversial episodes of the war. Critics in Congress and elsewhere cited it as an example of the Army using outmoded tactics and taking high casualties against an elusive guerrilla enemy without gaining anything of value. He remained silent on the dispute until 1989, when he published a commentary on it in the Washington Post. Far from being a useless loss of life, he said, it resulted in U.S. forces gaining control of the Ashau Valley and denying the enemy important bases and avenues of supply.

“By any standard in a limited war, the battle was a success,” he wrote. “It probably saved thousands of U.S. and Vietnamese lives. When US troops were called home, they were able to withdraw from a secure area.”

He established his home in the Washington, DC in 1960, was was a former president of the Usher Society at St Mark’s Catholic Church in Vienna.

Survivors include his wife of 51 years, Marie W. Conmy of Vienna; four children, a sister, a brother, 15 grandchildren; and a great-grandchild.

The Third U.S. Infantry (The Old Guard) has lost one of its own. The entire regiment turned out for a final tribute and celebration of his life on Tuesday (26 April 1994).

Retired Colonel Joseph B. Conmy, 75, honorary Commander of The Old Guard, died of cancer Friday at home in Vienna, Virginia.

While speaking with family and friends during the day of his final tribute, two things were consistently mentioned: the way he cared for his men and his love for The Old Guard.

He first encountered the Third U.S. Infantry on March 12, 1919, when he was born into the unit at Fort Snelling, Minnesota, where his father, Joseph Sr, was a Company Commander. Little did he know that this was just the first of many meetings with The Old Guard. 43 years and two wars later, he would command the brigade. After growing up in the Army and traveling from post to post with his father, he decided to follow in his footsteps. The young man entered the United States Military Academy in 1939 and received an Infantry commission in 1943. He saw action in World War II, during which he received a Purple Heart, two medals for valor, and the Combat Infantryman’s Badge, according to retired Lieutenant General Frank A. Camm, Conmy’s West Point classmate who delivered his eulogy.

His bravery and valor resurfaced during his time in Korea. While there, he earned battlefield promotions to Major and Lieutenant Colonel as well as an additional Purple Heart, Combat Infantryman’s Badge and four medals for valor. After assignments at West Point, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and in Europe, was brought to Washington, D.C. as an intelligence officer at the Pentagon. There is where Conmy had his second encounter with The Old Guard.

His wife of 51 years, Marie, recalled her husband’s excitement over the unit. “We were attending a performance of ‘Torchlight Tatoo’ (now Twilight Tatoo) right here in Ceremonial Hall. Joe was fascinated. He looked at me and said, ‘That was the unit my father was in.'” Conmy placed a request with his superiors and his dream was realized when he assumed command of the unite in November of 1963. Conmy took command when The Old Guard was truly evolving as a ceremonial unit. Specialty units such as The Old Guard Fife and Drum Corps and the U.S. Army Drill Team were still in their infancy. While he was impressed with their ceremonial skills, Conmy felt the soldiers should be combat ready as well, Marie said. “He stepped up training,” she said, “and insisted that they be combat ready as well as a unit that looked good.”

Stories of his compassion and care for his soldier are known my many who knew him. Camm recalled a time when the Commander needed new shoes. “The soldiers were only issued one pair of shoes and with all of the marching they did, they would go through them pretty fast. If a soldier wanted a new pair, he would have to buy them himself. Like his other soldiers, Joe eventually needed new shoes as well. He called the supply sergeant and requested a new pair. “The soldiers he worked with knew how he felt about his troops and didn’t really think he would ask for another pair knowing his soldiers didn’t have the same privilege. So the assistant S-4 asked him about it, and sure enough, Joe didn’t know about the policy. He commended the soldier for filling him in and didn’t take the shoes.” Conmy was regimental Commander until 1968.

His next assignment was as Commander of the 3rd Brigade, 101st Airborne Division in Vietnam. His final time in combat brought him his third Purple Heart, his third CIB (one of 230 soldiers every earning three) and 3 more medals for valor. According to Camm, Conmy served in more ground combat situations that anyone lse from the Class of 1943. “He’s our hero,” he said. “He was more than I could convey in the eulogy.

Even after his full 30-year career, Conmy still kept close ties with the military. He and his wife retired to nearby Vienna, Virginia. In 1985, he served as the technical advisor during the filming of the movie “Gardens of Stone.” In 1988, was selected as the honorary Colonel of the Third U.S. Infantry. As a tribute to Conmy’s service to the unit, The Conmy Awards have been established. The competition consists of common-tasks and skills in which representatives from the different companies compete. Just as soldiers under his command laid hundreds of veterans to rest some 30 years ago, Old Guard soldiers laid their former Commander to rest in Arlington National Cemetery. (Section 7-A)

Courtesy of His Classmates

United States Military Academy Class of 1943

Joseph Bartholomew Conmy, Jr.

No. 13255 • 12 March 1919 – 22 April 1994

Died in Vienna, Virginia, aged 75 years

Interment: Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Virginia

JOE CONMY WAS A SOLDIER’S SOLDIER, a man born into the 3rd Infantry Regiment, and who left this life the honorary colonel of that same regiment. In the late 1960s, he was proud to command the unit with which his father had served.

Joe wore three awards of the Silver Star for gallantry in action, three awards of the Combat Infantry Badge, and three Purple Hearts — the indication that he shared the hazards of infantry troops in prolonged combat.

Joe was born in Minnesota and survived an education interrupted by his father’s military orders. In 1937, he graduated from Leilehua High School, Hawaii, and spent a year at the West Point Prep School there. Failing to gain an appointment, he joined two future classmates at St. Thomas College in St. Paul, Minnesota, his father’s old college. He earned a partial scholarship, was the janitor of the Science Building, and worked for the Athletic Department.

He finally won an appointment, joining many of us who had followed him at the West Point Prep. Joe had no problem staying above the middle of the class and climbed upward in his final two years. He was on the C Squad basketball team, B Squad cross-country, and won his letter in A Squad track in the 440 and the high jump. He also found time for the 100th Night Show and several class committees. He worked with the Catholic Chapel, where he met a lovely, blonde singer whom he was asked to escort. He and Marie Wilker were married on graduation day in Pleasantville. They had four children whose birthplaces reflect the variety of Joe’s assignments: Bart born at Fort Lewis; John in Honolulu; Mary Alice at West Point; and Barbara Ann in Paris.

oe joined the 44th Infantry Division at Fort Lewis and deployed with them to Europe in August 1944. As a company commander in the 114th Infantry Regiment, he was wounded after a month of combat. Returning to his unit, Joe became S-3 of the 1st Battalion of the 114th. By the end of the war, he had won two Bronze Stars, the Purple Heart, and the Combat Infantryman Badge.

In between wars, Joe and Marie moved to Hawaii for a three-year tour with the ROTC. The 1949–50 Advanced Course led to orders for the 7th Infantry Division, which Joe joined just as they left for Korea. While in Korea, Joe was promoted to major and then to lieutenant colonel. He won his first Silver Star, three more Bronze Stars for valor, the Air Medal, another Purple Heart, and another Combat Infantryman Badge. He rapidly was becoming our pre-eminent doughboy, and returned to USMA as a tactical officer.

Between 1955–60, the Conmys were at C&GSC, in France with EUCOM, and at the Army War College. Then he began eight years in Washington, four in ACSI and the Office of the Army Chief of Staff, and four as commander of the Old Guard — a dream come true: commanding the unit into which he had been born. The trouble was that Joe was so good at his job that he was held on long past the time he wanted to go to Vietnam. In fact, Lyndon B. Johnson used another tall USMA grad and Joe on his overseas flights to dazzle the public. Those of us at one Pacific conference saw the Presidential plane arrive, doors open, and Joe and Hugh come down in immaculate whites to draw sabers and form a welcoming arch for LBJ as he debarked.

Finally, Joe was released to go off to his third Infantry war. As commander of the 3rd Brigade of the 101st Airborne, he was awarded two more Silver Stars; the Legion of Merit; two Distinguished Flying rosses; another Bronze Star for valor; 15 Air Medals; his third Combat Infantryman Badge; and his third Purple Heart. That was the peak of his career. On return to the U.S., he spent three years assigning colonels and a year as liaison to the Inaugural Committee before retiring at 30 years with two more awards of the Legion of Merit.

The controversy over Vietnam spilled into Joe’s life when a former Army officer criticized Hamburger Hill, one of Joe’s brigade battles, as allowing leaders to win promotions by applying World War II standards to guerilla warfare and claiming victory when the enemy slid away. Joe finally spoke out in a Washington Post article of 27 May 1989:

“By any standard in a limited war, the battle was a success. It probably saved thousands of American and South Vietnamese lives . . . The controversy surrounding the battle was generated stateside by politicians and members of the press who wanted the war to end but seemed to have no real solutions for ending it. However well-intentioned their criticisms, the net results were the enshrinement of inaccuracy, harassment of the troops and the denigration of Vietnam service.”

Joe later had an opportunity to ensure accuracy when he was made technical director of a Hollywood film on Hamburger Hill. He also supervised a film on the Old Guard and Arlington Cemetery.

He thoroughly enjoyed the 50th Class Reunion and looked forward to the 55th, but an insidious cancer gained a foothold. He suffered through increasing pain with a stoic good humor. Finally he was taken, and laid to rest in the cemetery where he had served so long. The Old Guard did “their colonel” proud. A fine soldier joined that part of the Long Gray Line which “. . . we see not.”

Joe is survived by his widow, Marie; by his sons Bart, who lives in Florida, and John, who lives nearby in Richmond; by Mary Alice Gill of Texas; and by Barbara Lowel of California. A brother and sister, 15 grandchildren, and one great-grandchild also survive him.

A premier Infantry soldier has left us. Joe Conmy was never concerned with the outward trappings of his success as a battlefield leader; he was a simple man who felt a calling to command troops in battle. One former soldier said, “Whenever I looked around the emptiness of the battlefield, there was ‘Iron Raven’ standing right behind us.”

Joe did not write the Washington Post article in his own defense but to protect the reputation his soldiers had earned in battle. Even as he moved into the twilight hours of his life, his talk was of old battles and giving directions to soldiers whose names have long since faded into history. Joe died as he had lived — an Infantry soldier to the end. We are proud to be his classmates.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard