IN MY FATHER’S FOOTSTEPS:

A MARINE’S DAUGHTER TRACKS DOWN DAD’S WORLD WAR II HAWAII

by Carole Terwilliger Meyers

On the 50th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor, George Bush declared, “The war is over. It is history.” But the war is not over. And it never will be over for those who fought in it, or for their children, who lived with the aftermath of human anguish.

As my cruise ship sails out of the harbor, the soft, warm tropical air caresses my skin. I look out over the twinkling lights of Waikiki–just as my dad did when he sailed off to surprise the Japanese in battle in the Marshall Islands on January 15, 1944. Except that my father’s troop ship, holding about 2,000 men, was completely dark, and the sailors weren’t permitted even to whisper. Their exit had to be silent due to the secrecy of their mission.

Just a bunch of excited American kids waiting to test their teenage muscles, they believed they were sailing off to fight gloriously in retaliation for the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, in which more than 2,300 American military personnel were killed–1,177 of whom were sailors and Marines aboard the USS Arizona. But in reality they were sailing straight into hell, and they were still too young and too innocent to be suitably afraid. That night my dad found himself floating past the sunken Arizona–a ship he had sailed on five times during his first enlistment. He has never put in words what that felt like.

My dad, Earl Walter Terwilliger, a three-stripe sergeant, was only 22 years old. He says that while he and his fellow Marines were waiting there in Honolulu Harbor to sail out to the unknown of battle in the Pacific (which turned out to be on Engebi Island in the Eniwetok Atoll, where he remembers landing under fire and proudly recalls his unit setting a world record for taking an island–eight hours and two minutes), he could hear the sounds of people partying on shore. It is fitting that the music I hear played by my cruise ship’s send-off band over 50 years later is from that era and includes the nostalgic, upbeat “In the Mood.”

The ship I am sailing on is a testament to what humankind can accomplish in peacetime, and also a testament to what my father and his buddies went to war for–to assure that a party ship full of happy people can sail out of this harbor for a peaceful pleasure cruise.

While I enjoy accommodations in a spacious stateroom with a porthole, my dad’s lot was sleeping crammed into a bunk, or hanging from a hammock, or stuffed into a bedding roll on a crowded deck. While I dine on fresh fruit and the bounty of the Islands in a full-service dining room, he was chowing down on rations or eating in the mess hall (though he complains about none of this and remembers being well-fed). He sailed anticipating adventure, but instead found horror; I sail anticipating relaxation, but discover enlightenment.

I am taking this most American of cruises primarily for pleasure, but also with the intent of using shore excursions to check out some of the military sites in Hawaii my dad has spoken of. I want to follow his footsteps, to try to catch a glimpse of his stride through time, just like as a child I trailed behind while trying to keep up with his fast-paced feet, usually shod in combat boots.

It wasn’t until my dad was in his 70s that I got the real story of his military service. As a child, stories of “The War” held little interest for me. Periodically he would ceremoniously open his footlocker and take out his battlefield souvenirs, among them his dog tags, the ripped helmet chin strap that deflected shrapnel from his head and probably saved his life, and a torn white Japanese flag with a big red dot in the center. I and my siblings would look at these objects with limited understanding of their history and importance, and unfortunately he would tell us very little about how he acquired them. Then he carefully packed everything back into a past he kept stuffed securely in his trunk.

The full tragedy of his war experience didn’t come back to haunt him until he retired and finally had time to reflect. Then, when I was an adult with grown children of my own, just prior to my leaving on a vacation to Hawaii, Dad mentioned that he had been stationed on Maui. He told me he trained there with the 22d Marines (he later joined the 5th Amphibious Corps and previously fought with the 3d Marine Raiders in the Wallis Islands), doing drills on the snow-covered Haleakala volcano to “thicken our blood” for the coming Pacific battles. Something finally clicked. I was intrigued. I wanted to know more.

Our first port is Nawiliwili Harbor, near Lihue on Kauai, where on a shore excursion I face some of my own demons by remaining in a kayak that I am sure will dump me in the drink. Instead of drowning, I get the hang of it and enjoy a peaceful float down the Huleia River, the very river that Indiana Jones swung over on a rope while making his daring movie escape. In a fabulous ending to the excursion, we trample barefoot over a muddy path through a dense, jungle-like expanse, bringing to mind my dad’s tale of contracting filariasis (an illness brought on by a particular kind of mosquito that deposits eggs in the bloodstream which then hatch into worms) in the violent circumstances of his very different jungle visit in the Wallis and Marshall Islands. The parasitic worms blocked off the blood vessels in his arm, which swelled to three times its normal size as he developed elephantiasis. (But Dad credits the mosquitoes that bit him, and luck, with saving his life. Because of his disability, he was sent back home through New Caledonia and wound up missing some of the war’s even nastier, more bitter battles. And he also credits that training stint in Maui with actually thickening his blood and thus keeping him from bleeding to death from the wounds that earned him a Purple Heart.)

Our next port is Wailuku on Maui, where my dad’s unit R&R’d. Here my husband and I rent a car so we can go wherever our leads direct us. Wailuku is such a sleepy town that it requires a real stretch to imagine it jumping with Marines on their night off. It is so untouristy that I’m unable to find a promotional t-shirt or a baseball cap to send back to my dad. But while I’m searching for such a souvenir, I start chatting in the town music shop with a good-natured, spacey fellow who seems interested in my mission. He tells me that the World War II “jarheads,” as he calls them (a slang term referring to their general stubbornness), trained out at Haiku. He thinks the training grounds are a park now.

Dad never mentioned Haiku, and doesn’t remember it when I describe it to him later, but we find the town on the map and set out. In hip Paia we pick up a picnic lunch and drive on to Honomanu Bay. Here we are entertained by colorful windsurfers dancing on the turquoise surf while we eat, stretched out in the warm sand. I realize later that this fabulously beautiful spot must have been what my dad and his buddies saw, minus the windsurfers, as their buses and trucks rumbled down the zigzagging, then-unpaved mountain road into town.

When I ask the clerk in Haiku’s little town store where the Marine base was in World War II, she hasn’t a clue. The only other person in the store pipes up that there is a memorial park just outside of town. A few minutes later we arrive at a large open field edged surprisingly with mature eucalyptus trees–I was expecting coconut palms–and with a sign declaring it the Fourth Marine Division Memorial Park. As we walk over the expanse of grass, I picture the field filled with tents and 5,000 excited young men, all of whom were volunteers. (My dad says the Marine Corps is “a year older than the United States.” It began as a group of sailors who knew how to fire guns and is the only branch of the armed services made up entirely of enlisted men who volunteer their lives for defense.)

Dad says they were told never to eat any fruit found on the ground, because it might be contaminated. So, while training in paradise, these young men devised a way to let off steam, practice their battle skills, and get a snack all at the same time: One soldier would shoot down a coconut, aiming at the stem, while another caught it. Then they used their combat knives to cut the nuts open. (This was the same knife my daddy would later grab from his bedstead when I came to his room as a child, afraid of suspicious night noises outside my bedroom window. He then stomped right out into the night, as if on a skirmish, in search of the enemy. Once a Marine, always a Marine. However, he says he gave up his guns–among them two Colt 45 automatics that he once holstered cowboy-style onto each hip–when he left the service. He says he fired his last shot at the enemy and has never again discharged a gun.) These soldiers also practiced playing dead as hairy black banana spiders crawled over their bodies.

It was probably also here that this young man, my father, transformed his childhood talent for pitching baseballs into a life-saving skill at lobbing grenades. Later, in combat, instead of throwing balls to help his team win a game, he would be tossing grenades to keep his buddies alive.

After the war, the people of Maui erected a simple memorial in the park. I cry as I read: THIS PLAQUE MARKS THE SITE OF CAMP MAUI WORLD WAR II HOME OF THE 4TH MARINE DIVISION AFFECTIONATELY AND PROUDLY CALLED “MAUI’S OWN.” This gratitude surprises me. I have to tweak my memory to recall that at the time of World War II Hawaii was not a state. I had assumed the local residents might be annoyed by the Marines invading their town and island. Instead, the people of Maui very much appreciated what these young men were sacrificing for them.

Unlike so many other men in that brutal war, my dad came back alive. But like most men who survived, he was scarred, both on the outside and the inside. On the outside, he suffered a head injury from shrapnel that scarred his scalp and brain, causing him to have occasional epileptic seizures. (I’ve seen him suffer a seizure only once. It occurred recently while he was telling me the devastatingly emotional story of his innocence lost as a Marine in battle, “earning” his Purple Heart. He broke down as he told me about Corporal Snyder, who came to check on my dad’s injuries after he was hit in the head by shrapnel. Part of the corporal’s face was blown away as my father watched, horrified. Dad never saw him again and doesn’t know if he survived.)

On the inside, he is an open wound. Like the Vietnam vets, he still has flashbacks and bad dreams. And like the Vietnam vets, he came home to a world where no one really wanted to hear the true story of what he had been through. So, like any Marine worth his salt, he kept all the horror, all the blood and guts, inside, where he thought they belonged. A few years ago when he joined a Vietnam vets therapy group, I found it surprising that these younger men welcomed him, that they had no problem accepting him. But I shouldn’t have been surprised, because they all had fought, and are still fighting, the same battle. War, it turns out, is war. (In light of this, what a shame it is that the Veteran’s Administration cancelled his group, and others like it, due to lack of funding. It is my opinion that all men who experience battle should be decompressed with group or individual counseling that addresses their trauma, and that it should be paid for by “we the people.”)

After strolling through the memorial park, watching happy children frolicking on the contemporary playground, we continue driving on up the mountain. I try to imagine what my father had been feeling when he went up-country on “blood-thickening” excursions to the snow. We are running late and have to get back to the ship, so we turn our car around before reaching the top, where, even with no snow, it is still quite chilly.

Our ship makes several more stops. On the Big Island we drop the search for the past and vacation for a while, walking lush paths through exotic landscaping at the spectacular Hawaii Tropical Botanical Garden in Hilo, and diving in the Atlantis submarine off Kona. I have enough of this submarine in 45 minutes to last a lifetime and cannot help drifting into a daydream about the men who, more than 50 years ago, served their country squashed into such tight quarters during seemingly endless tours of duty. I find out later from my dad that he and his fellow Marine Raiders were often picked up after a battle, in the South Pacific night, by submarines. He says they would escape by sliding down the torpedo tube, which was only about a foot and a half in diameter, landing on mattresses.

Back in Honolulu, at the end of our voyage, we join a post-cruise shore excursion to the USS Arizona Memorial in Pearl Harbor. This is Hawaii’s second most popular visitor attraction. (Number one is the national Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific at Punchbowl.) On the bus ride there, the mood is somber and the driver cracks not a joke. We learn that one of our tour members is a rare survivor of the Japanese attack.

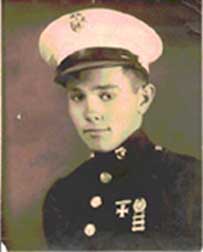

Emotions start heating up in the Arizona museum, where I view letters home from very young men, many just teenagers, and see images of baby-faced soldiers that look like my dad in his enlistment photo, like my son in his high school graduation picture.

After a silent boat ride out to the memorial, which floats above the famous sunken ship without touching it, I place my fragrant orange flower lei among the many purple orchid and white plumeria lei already piled at the base of the marble wall engraved tightly with the names of all the men who died here. Though traditionally lei are left for the crew that went down on the Arizona, I leave mine in memory of all servicemen. As tinkling bells play “Amazing Grace” and then the “Marine’s Hymn,” I, and many others, weep. A very light rain seems to be saying that the heavens are mourning, too, for these precious lost lives. I am crying also for what my dad went through as a young man, as he says he cries for today’s young soldiers.

Before leaving, I stop at the gift shop and get Dad some souvenirs of the Arizona . They are doing a booming business here, making me wonder how many other fathers out there have lived a similar story.

My father is finally getting better. His descent into despair has flattened out, and he seems to have his seizures under control. But he is stubborn and doesn’t always take his medicine. He is also drinking less, and his lips, once loosened to me by liquor, have tightened up again as taut as a blanket on a military cot awaiting morning inspection.

And now that I am finally listening, now when I am in fact taking notes when he rattles on about the “The War,” my dad seems to have less interest in talking. Isn’t that just like a jarhead?

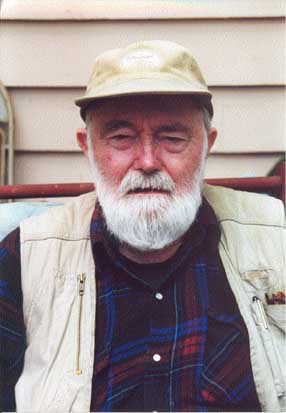

Back from my cruise now for almost a year, it took me this long to finish writing, to fit the pieces together into a pattern. But it has taken my dad a lifetime. Back now for over 50 years from his immersion trip into World War II, he still hasn’t put all the pieces together. Perhaps he never will. The last time I visited him this 79-year-old Ernest Hemingway look-alike said, “There is an old saying that Marines never die, they just fade away, and I’m fading.”

(Carole Terwilliger Meyers is the founding publisher at Carousel Press and is the author of WEEKEND ADVENTURES IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA. She lives in Berkeley, California, where she keeps her father’s well-worn combat compass on her desk pointing her in the right direction. Her father was born and raised in Poughkeepsie, New York, and now lives in Eugene, Oregon. This article won First Place in the Society of American Travel Writers 2000 contest and appears in the anthology Travelers’ Tales: Hawaii.)

Afternote: My dad is now fighting a new battle in a nursing home for dementia sufferers. I visited him recently and was pushing him in his new wheelchair, which he actually seemed to be enjoying, and he looked back at me over his shoulder and ordered, “Let’s punch it!” He still has plenty of spirit. Semper Fi.

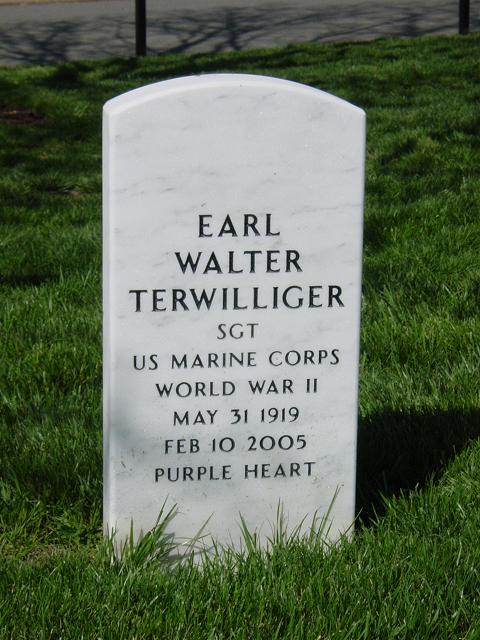

NOTE: Sadly Earl Walter Terwilliger lost his final battle on 10 February 2005. He was laid to rest with fullmilitary honors at Arlington National Cemetery.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard