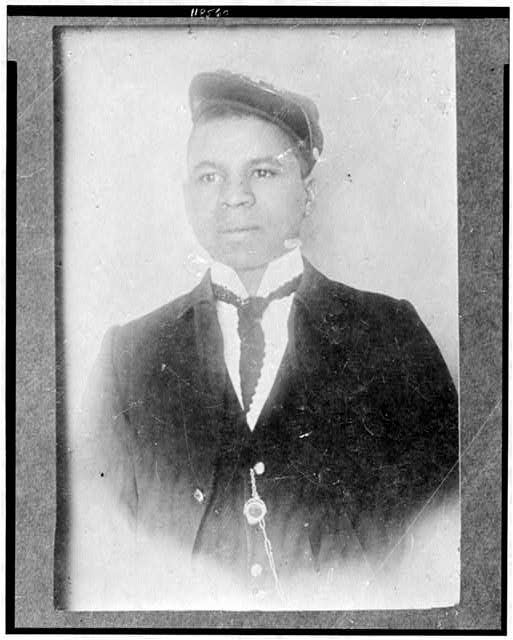

Born in Washington, D. C. on December 28, 1866, he earned the Medal of Honor during the Spanish-American War, while serving in Troop H, 10th United States Cavalry at Tayabacoa, Cuba, on June 30, 1898. He was a member of the all-black 10th Cavalry, five of whom received the Medal of Honor.

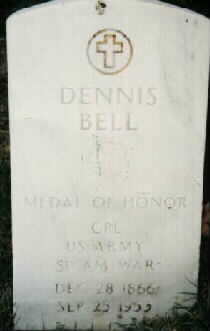

He died on September 25, 1953 and was buried in Section 31 of Arlington National Cemetery.

Centennial Flashback: 1899 Medals of Honor bucked a dishonorable trend

Monday, May 31, 1999

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

In a city that celebrates its heroes, Dennis Bell is almost forgotten. Time may have blurred his achievements, but what Bell did resonated in an era when segregation was legal and lynchings bordered on being ordinary. His story stretches back a century, to when war broke out between the United States and Spain.

Bell, then a 31-year-old Pittsburgh coal miner, threw down his shovel, picked up a rifle and joined the 10th U.S. Cavalry. He was shipped to Cuba, where fighting for control of the island was ferocious.

Library of Congress

On the evening of June 30, 1898, near a town called Tayabacoa, Bell and three other soldiers accepted what seemed to be a death sentence.

They volunteered to wade into a battleground hot with Spanish gunfire to try to rescue six wounded Cubans, who were fighting on the side of the Americans. Bell’s commander, Lieutenant C.P. Johnson, called it “an almost foolhardy mission.”

Against extraordinary odds, Private Bell and his three buddies pulled the Cubans from the sea, where they were hiding to evade enemy bullets. Then the soldiers hauled the wounded men to safety.

For their heroism, all four Americans received the Medal of Honor 100 years ago, on June 23, 1899. The Medal is the country’s highest award for bravery.

In addition to Bell, the award went to Private Fitz Lee of Dinwiddie County, Virginia, and Corporal George Wanton and Sgt. William H. Thompkins, both of Paterson, New Jersey.

Their story has a kicker: All four were black.

In the 20th century, black soldiers were almost never considered for the Medal of Honor, much less awarded it. Yet in the 1890s, when racism poisoned Northern cities and an average of four blacks a week were lynched in the South, the government bestowed hero status on Bell and the other black soldiers.

“It was a terrible period in America, so it’s interesting that there was more equality in the military than in society at large,” said Marvin Fletcher, a history professor at Ohio University and author of a book on black soldiers of that era.

“By World War I, attitudes toward blacks changed. There was much greater reluctance to award them medals or to recognize them for accomplishments, as racism became more pervasive,” Fletcher said.

No black soldiers were selected for the Medal of Honor immediately after World Wars I or II. Ultimately, a handful received the award, but not until decades had passed.

Freddie Stowers, an Army corporal in World War I, was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1991 — 73 years after he was killed in action.

Seven black soldiers from World War II received the Medal of Honor in 1997, almost 52 years after the war had ended. By then, only one of them, Vernon Baker of St. Maries, Idaho, was still alive.

The Spanish-American War, which ended in 1899, would have seemed an even less-likely time for America to celebrate its black soldiers.

Runaway violence occurred against black people during the 1890s, often without consequences for the thugs who perpetrated it.

Just two months before Bell and his three unit mates received the Medal of Honor, about 20 black men were lynched in Little River County, Arkansas. Throughout the decade, about 200 lynchings of black people occurred each year.

The country was so steeped in racism that segregation had been sanctioned by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1896 case of Plessy vs. Ferguson. The justices’ ruling legalized “separate but equal” schools and public accommodations.

Bell knew from personal experience that separate meant unequal.

When he enlisted in the Army in 1898, he was assigned to an all-black cavalry unit. Bell sailed to Cuba on the SS Florida, only to find on arrival that the Army had no horses for him or his comrades.

These dismounted soldiers were assigned to ship duty, for which they had no training. Nonetheless, they used this strange circumstance as an opportunity to excel.

On the evening of the great rescue, Lieutenant Johnson was inclined to leave the wounded Cubans rather than chance more lives to save them.

“The service was of such a hazardous nature as to make me very reluctant to risk the loss of any of my small party of regulars,” Johnson wrote. “Four expeditions, composed of Cubans and the immediate friends of the wounded men, had already failed because of the extreme danger.”

So Bell, Lee, Wanton and Thompkins first had to fight for the chance to attempt the rescue. Then they had to fight the Spaniards.

They won both battles.

“They pulled unhesitatingly for the shore, picked up the wounded who were hiding in the water and successfully returned to ship,” Johnson said in his hand-written letter nominating all four for the Medal of Honor.

A century ago, the award was significant, though not as hallowed as it would become.

“The Medal of Honor was the only award for valor up until World War I, so it did not carry the kind of legendary status that it would later have,” said Richard Kohn, a history professor at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

As other military decorations for bravery were created, the Medal of Honor became more exceptional and more coveted.

Even so, the U.S. military of 1899 was far from colorblind. It probably broke with custom by openly designating black men as heroes worthy of its Medal of Honor.

“My sense is that recognition for those four soldiers was pretty unusual,” said Dickson D. Bruce, a history professor at the University of California-Irvine and an author of books about American life in the 1890s. “The period around ’98 or ’99 was one in which things were going backward for blacks. There was actual regression in race relations, so this would seem uncommon.”

Bell, originally from Washington, D.C., slipped back into anonymity after the war. But a National Archives file on his heroism recorded one other noteworthy encounter with the military.

Bell wrote a letter to the Army on March 3, 1906, in which he revealed that he had lost his Medal of Honor while in Alexandria, Virginia.

“I was not drinking, was not in bad company, and I have no idea when, where or how I lost the Medal,” he wrote.

The government issued him a replacement, no questions asked.

Bell died in 1953 when he was 86 years old. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. His status as a Medal of Honor recipient is listed on his gravestone.

Fletcher, the Ohio University professor, believes Bell and his comrades probably ended an era. Soon after their achievement, Fletcher said, unadulterated bigotry took over the military chain of command.

“I look at what happened with these men as evidence that blacks could be rewarded for outstanding behavior,” he said. “But when we reached World War I, it had become impossible for blacks to receive that kind of recognition.”

By then, Dennis Bell’s achievements were buried in government archives that were growing dusty.

BELL, DENNIS

Rank and organization: Private, Troop H, 10th U.S. Cavalry. Place and date: At Tayabacoa, Cuba, 30 June 1898. Entered service at: Washington, D.C. Birth: Washington, D.C. Date of issue: 23 June 1899.

Citation: Voluntarily went ashore in the face of the enemy and aided in the rescue of his wounded comrades; this after several previous attempts at rescue had been frustrated.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard