United States Senator

Click Here For A Collection Of Obituaries

Click Here For Church Services

Click Here For Burial Information

27 August 2009:

With a bugler playing taps, a rifle squad firing a salute and pallbearers representing each branch of the military, Senator Edward M. Kennedy will be laid to rest in a private funeral at Arlington National Cemetery on Saturday.

Plans call for Kennedy to be buried in early evening near his slain brothers, President John F. Kennedy and Senator Robert F. Kennedy. The ceremony will be closed to the public but covered by a press pool at the hillside cemetery for military heroes and other figures from American history.

Some details of Saturday’s burial have yet to be decided, said Colonel Daniel Baggio, chief of staff for the U.S. Army Military District of Washington at Fort McNair.

A traditional ceremony for a member of Congress would include joint pallbearers to carry the flag-draped casket from the hearse to the grave site; that is, eight service members from the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps and Coast Guard, Baggio said. A seven-member rifle squad will also fire three volleys in salute.

Among its responsibilities, the military district has ceremonial duties in the capital, performed by the Army’s 3rd U.S. Infantry Regiment or “The Old Guard.”

If the Kennedy family chooses to have a graveside eulogy or prayer, it would be seven members of the regiment who would perform the rifle salute at the end — and its bugler who would play taps.

An officer from the regiment also would present the folded flag to the family.

A hillside at Arlington National Cemetery that is already the final resting place for prominent members of the Kennedy family will also be the burial site of Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy.

An official familiar with the arrangements says Ted Kennedy will be laid to rest there, most likely near the grave of his brother Robert. Nearby are the graves of John F. Kennedy and his widow, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. An eternal flame marks that spot.

A senior defense official says the Kennedy family some time ago approached the Army to explore the possibility of burying the senator at Arlington. It’s the nation’s most celebrated burial ground of fallen members of the military, and of giants in American history.

Kennedy is eligible for burial there by virtue of his service in Congress and his two years in the Army.

A source says the body of Kennedy will lie in repose at Boston’s Kennedy library with a funeral planned at a nearby church.

“Edward M. Kennedy – the husband, father, grandfather, brother and uncle we loved so deeply – died late Tuesday night at home in Hyannis Port, We’ve lost the irreplaceable center of our family and joyous light in our lives, but the inspiration of his faith, optimism, and perseverance will live on in our hearts forever. We thank everyone who gave him care and support over this last year, and everyone who stood with him for so many years in his tireless march for progress toward justice, fairness and opportunity for all. He loved this country and devoted his life to serving it. He always believed that our best days were still ahead, but it’s hard to imagine any of them without him.”–Statement from the Kennedy Family

The President spoke at 9:57 this morning at Blue Heron Farm in Chilmark, Massachusetts:

THE PRESIDENT: I wanted to say a few words this morning about the passing of an extraordinary leader, Senator Edward Kennedy.

Over the past several years, I’ve had the honor to call Teddy a colleague, a counselor, and a friend. And even though we have known this day was coming for some time now, we awaited it with no small amount of dread.

Since Teddy’s diagnosis last year, we’ve seen the courage with which he battled his illness. And while these months have no doubt been difficult for him, they’ve also let him hear from people in every corner of our nation and from around the world just how much he meant to all of us. His fight has given us the opportunity we were denied when his brothers John and Robert were taken from us: the blessing of time to say thank you — and goodbye.

The outpouring of love, gratitude, and fond memories to which we’ve all borne witness is a testament to the way this singular figure in American history touched so many lives. His ideas and ideals are stamped on scores of laws and reflected in millions of lives — in seniors who know new dignity, in families that know new opportunity, in children who know education’s promise, and in all who can pursue their dream in an America that is more equal and more just — including myself.

The Kennedy name is synonymous with the Democratic Party. And at times, Ted was the target of partisan campaign attacks. But in the United States Senate, I can think of no one who engendered greater respect or affection from members of both sides of the aisle. His seriousness of purpose was perpetually matched by humility, warmth, and good cheer. He could passionately battle others and do so peerlessly on the Senate floor for the causes that he held dear, and yet still maintain warm friendships across party lines.

And that’s one reason he became not only one of the greatest senators of our time, but one of the most accomplished Americans ever to serve our democracy.

His extraordinary life on this earth has come to an end. And the extraordinary good that he did lives on. For his family, he was a guardian. For America, he was the defender of a dream.

I spoke earlier this morning to Senator Kennedy’s beloved wife, Vicki, who was to the end such a wonderful source of encouragement and strength. Our thoughts and prayers are with her, his children Kara, Edward, and Patrick; his stepchildren Curran and Caroline; the entire Kennedy family; decades’ worth of his staff; the people of Massachusetts; and all Americans who, like us, loved Ted Kennedy.

DEATH OF SENATOR EDWARD M. KENNEDY

BY THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

A PROCLAMATION

Senator Edward M. Kennedy was not only one of the greatest senators of our time, but one of the most accomplished Americans ever to serve our democracy. Over the past half-century, nearly every major piece of legislation that has advanced the civil rights, health, and economic well-being of the American people bore his name and resulted from his efforts. With his passing, an important chapter in our American story has come to an end.

As a mark of respect for the memory of Senator Edward M. Kennedy, I hereby order, by the authority vested in me by the Constitution and laws of the United States of America, that the flag of the United States shall be flown at half-staff at the White House and upon all public buildings and grounds, at all military posts and naval stations, and on all naval vessels of the Federal Government in the District of Columbia and throughout the United States and its Territories and possessions until sunset on August 30, 2009. I also direct that the flag of the United States shall be flown at half-staff until sunset on the day of his interment. I further direct that the flag shall be flown at half-staff for the same periods at all United States embassies, legations, consular offices, and other facilities abroad, including all military facilities and naval vessels and stations.

IN WITNESS WHEREOF, I have hereunto set my hand this twenty-sixth day of August, in the year of our Lord two thousand nine, and of the Independence of the United States of America the two hundred and thirty-fourth.

BARACK OBAMA

There was a time 40 years ago, right after the assassination of his brother Robert, when it looked like Edward Kennedy would become President someday by right of succession. The Kennedy curse, the one that had seen all three of his brothers cut down in their prime, had created for him a sort of Kennedy prerogative, or at least the illusion of one, an inevitable claim on the White House. For years he seemed like a man simply waiting for the right moment to take what everybody knew was coming his way.

Everybody was wrong. Ted Kennedy would never reach the White House. His weaknesses – and the long shadow of Chappaquiddick – were an obstacle that even his strengths couldn’t overcome. But his failure to get to the presidency opened the way to the true fulfillment of his gifts, which was to become one of the greatest legislators in American history. When their White House years are over, most Presidents set off on the long aftermath of themselves. They give lectures, write books, play golf and make money. Jimmy Carter even won a Nobel Prize. But every one of them would tell you that elder-statesmanship is no substitute for real power.

Because Kennedy never made it to the finish line, he never had to endure a post-presidential twilight. Instead, by the time of his death on August 25, 2009, in Hyannis Port at the age of 77, he had 46 working years in Congress, time enough to leave his imprint on everything from the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to the Edward M. Kennedy Serve America Act of 2009, a law that expands support for national community-service programs. Over the years, Kennedy was a force behind the Freedom of Information Act, the Occupational Safety and Health Act, and the Americans with Disabilities Act. He helped Soviet dissidents and fought apartheid. Above all, he conducted a four-decade crusade for universal health coverage, a poignant one toward the end as the country watched a struggle with a brain tumor. But along the way, he vastly expanded the network of neighborhood clinics, virtually invented the COBRA system for portable insurance and helped create the laws that provide Medicare prescriptions and family leave.

And for most of that time, he went forward against great odds, the voice of progressivism in a conservative age. When people were getting tired of hearing about racism or the poor or the decay of American cities, he kept talking. When liberalism was flickering, there was Kennedy, holding the torch, insisting that “we can light those beacon fires again.” In the last year of his life, with the Inauguration of Barack Obama, he had the satisfaction of seeing a big part of that dream fulfilled. In early 2008, when Obama had just begun to capture the public imagination, Kennedy bucked the party establishment. Just before Super Tuesday, the venerable Senator from Massachusetts enthusiastically endorsed the young Senator from Illinois, helping propel Obama to the Democratic nomination and ultimately the White House.

Caroline Kennedy, Barack Obama, Edward M. Kennedy 2008 Photo

So does it matter that Kennedy never made it to the presidency? Any number of mere Presidents have been pretty much forgotten. But as the Romans understood, there can be Emperors of no consequence – and Senators whose legacies are carved in stone.

Rose Kennedy wanted a family. Joe Kennedy wanted a dynasty. They both got what they wanted, but only for a time. Joe had made a fortune in film production, liquor, real estate and stocks. But he wasn’t just a businessman. In the scope of his ambitions and schemes, he was something out of Shakespeare. He married Rose in 1914, and as their children arrived, he formed the conviction not only that the boys belonged in public life but that one of them, maybe more than one, should be President of the United States.

This was the atmosphere that Ted was born into on February 22, 1932 – the last of the nine Kennedy children. But from the start, he had three elder brothers as a buffer between himself and the worst of the old man’s ambition for his sons. All the same, he grew up at some distance from his parents. Over the years, Joe and Rose had become increasingly estranged. Overweight and lonely, Ted was shuttled through a succession of boarding and day schools, but he grew into an athletic, good-looking teenager, one who ambled into Harvard, where Jack and Bobby had gone before him.

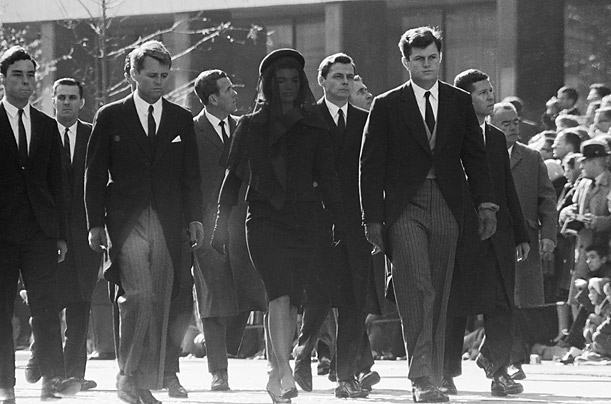

The Kennedy Family

He hadn’t been at Harvard long before he screwed up in a way that would come back to haunt him years later. In his freshman year, Kennedy was having trouble with a Spanish class. There was a test coming up, and he needed to do well in order to be eligible to play varsity football the next year. With the encouragement of some of his buddies, Kennedy recruited a friend who was good at Spanish to take the exam in his place. The scheme backfired. The surrogate was caught, and both boys were expelled, though Harvard offered them the opportunity to be readmitted later if they showed evidence of “constructive and responsive citizenship.”

Kennedy’s abrupt next move was to join the Army, which sent him to Georgia to be trained as a military police officer and then, thanks to his father’s intervention, to Paris to serve as an honor guard at NATO headquarters. In the fall of 1953, he was readmitted to Harvard, where he majored in government. After graduation, he went on to study law at the University of Virginia. He was in law school when he met Joan Bennett, a senior at Manhattanville College, a small Catholic school in New York State that his mother and two of his sisters had attended. Not much more than a year after they first met, they married. Over the next nine years, they had three children: Kara, Edward Jr. and Patrick. (Joan also suffered three miscarriages.) But by 1982, the combination of her prolonged struggle with alcohol and his infidelities led them to divorce. Joan often found herself burdened by the effort required to fill the role of a Kennedy wife. Years later, sounding a bit like Princess Diana, she told an interviewer, “I didn’t have a clue what I was getting into.”

What she had gotten into was the Kennedys, a family whose family business was politics. Ted was still in law school when he was made campaign manager for Jack’s 1958 bid for a second term as Senator. Though the real decision-making was left to seasoned Kennedy operatives, the campaign put Ted in the field constantly to meet and greet voters. It prepared him for a future, coming soon, in which he would be the candidate. When Jack was elected to the White House in 1960, there were four years remaining in his Senate term. The family wanted Ted to succeed him, but at 28, he was two years below the minimum age for the Senate. So a Kennedy loyalist was chosen to fill the seat for a couple of years while Ted used the time to make himself plausible to the state’s voters as a man they should send to Washington. With Jack’s help, he attached himself to a Senate fact-finding trip to Africa. He toured Latin America, Israel and Berlin. On Election Day, with 54% of the vote, Kennedy beat George Cabot Lodge, a descendant of the Waspiest of New England political dynasties.

Edward M. Kennedy Campaigns For US Senate 1962 PHOTO

Ted had been in the Senate for less than a year when JFK went to Dallas the day Lee Harvey Oswald was lying in wait. Jack’s death was more than a personal tragedy for Ted. It was a watershed. It put him one step closer to assuming the Kennedy burden, the perennial quest for the heights. It marked the beginning of his transformation into a true public figure. As a first measure, Ted devoted himself to ensuring the passage of legislation that had been important to his brother, especially the civil rights bill JFK introduced the summer before his death. On June 19, Ted added his vote to the 73-to-27 majority that turned that bill into the historic Civil Rights Act of 1964. Then he headed to the airport to board a private plane that was to take him to the state Democratic Party convention in Springfield, Massachusetts. But as the plane made its descent into a fogbound Springfield airport, it struck a row of trees and somersaulted across an orchard. The pilot, Ed Zimny, died at the scene. A Kennedy aide, Ed Moss, died a few hours later. Indiana Senator Birch Bayh and his wife Marvella, who were also on board, survived with minor injuries. Kennedy suffered a broken back and a collapsed lung.

What followed was a five-month recovery, mostly spent immobilized in a hospital bed, and a lifetime of back pain. Yet when he returned to the Senate the following year, Kennedy set to work with the energy that comes to a man who gets a second chance at life. It wasn’t long before Ted scored a victory on another of Jack’s unrealized goals, the reform of immigration quotas to allow more arrivals from nations outside Northern Europe. One year later, he secured federal support for neighborhood clinics, marking the first time he applied himself to the problem of health care, the signature issue of his public life.

By 1967, Kennedy had also begun to speak out against the Vietnam War. Exasperation about Vietnam was one of the main reasons his brother Robert decided to seek the presidency in 1968. Then Bobby was shot down as well. His death was a crucial moment of recognition for Ted that the burden of the Kennedy legacy was now his to shoulder. For years he had been the Prince Hal of the Kennedy dynasty, the wayward son who would just as soon not inherit the kingdom. But now, at 36, he was the last of the line. There was no one else.

So when Hubert Humphrey lost to Richard Nixon in the fall, Ted instantly became liberalism’s last, best hope. There were people who thought he lacked Jack’s intellect or Bobby’s passion, that all his life he had merely trawled in their wake. But in his first speech after Bobby’s death, he was already sounding the cry that would be the great theme of his political life: “Like my brothers before me, I pick up a fallen standard. Sustained by the memory of our priceless years together, I shall try to carry forward that special commitment to justice, to excellence, to courage, that distinguished their lives.”

This was the moment when everyone assumed that the presidency would someday be his for the asking. But it was only a moment. On July 18, 1969, Kennedy hosted a reunion for six women who had worked at the center of Bobby’s presidential campaign. The gathering took place in a rented cottage on Chappaquiddick Island, just off Martha’s Vineyard. Around 11:15 that night, Kennedy asked his driver for the keys to his Oldsmobile so that he could leave the party with Mary Jo Kopechne, 28, a former aide to his brother. According to testimony he gave later at a judge’s inquest, he took a wrong turn onto an unlit dirt road and then across a small, unrailed wooden bridge. His car went over the side of the bridge and landed upside down in the water. Kennedy managed to escape. Kopechne did not.

There are questions about Chappaquiddick that have never been closed. Where was Kennedy going with Kopechne at that late hour? (At the inquest in January, he claimed that he was taking her back to her hotel in Edgartown.) Why did he wait until the following morning, 10 hours later, to report the accident to the police? (He said it was because he had been in a state of shock and confusion.) Was the real reason for delaying the report that at the time of the accident he was drunk? (He insisted he was not.) At the inquest, he testified that after escaping from the car, he dived back into the water seven or eight times in a vain attempt to free Kopechne. Then he made the mile-and-a-half walk back to the cottage, where the party was still underway, collected two male friends and returned with them to the car, where they also attempted to free Kopechne. When that proved impossible, Kennedy decided to return to his hotel across the water in Edgartown. But instead of summoning the night ferry, he chose to swim 500 feet across the bay.

The inquest concluded that Kennedy had lied when he said he was taking Kopechne back to Edgartown. It also ruled that his “negligent driving” appeared to have contributed to her death. By the time the inquest was complete, Kennedy had already entered a guilty plea to leaving the scene of an accident and received a two-month suspended sentence. But it would be truer to say he was sentenced to life under the cloud of Chappaquiddick.

Had it not been for that night, he almost certainly would have been a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1972. He stayed on the sidelines that year and in 1976 as well, even though in the aftermath of Watergate, that looked to be a winning year for the Democrats. It would be, but for Jimmy Carter.

Kennedy found new issues to throw himself into. In 1970 he introduced his first bill to establish a system of universal health-care coverage. He confounded people who thought of him as a doctrinaire liberal by pushing for airline deregulation and for required sentencing of convicted criminals. He promoted arms-control talks with the Soviet Union but also devoted himself to the cause of Soviet dissidents and would-be Jewish ÉmigrÉs.

It was Chappaquiddick as much as anything else that sabotaged his most serious attempt at the White House: his fight in 1980 to push Carter aside. Almost three decades later, that campaign is still a bit of a puzzle. His ideological differences with Carter never seemed great enough to justify a challenge to a sitting President of his own party. His main complaint was that Carter wasn’t moving forward fast enough on health care, “the great unfinished business on the agenda of the Democratic Party,” as he called it. In a televised interview on Nov. 4, 1979, just three days before he would launch his campaign, Kennedy gave CBS News correspondent Roger Mudd a notoriously rambling answer to the simple question “Why do you want to be President?” The man who had spent years on a trajectory to the White House still couldn’t say exactly why.

In the end, Kennedy won 10 primaries. Carter took 24, then sailed into the propellers of Ronald Reagan in the fall. But that failed campaign liberated Kennedy. He gave the best speech of his life at the 1980 Democratic National Convention, the speech of a man who had no intention of exiting the public stage. Because the White House was never again a serious option for him, he was free to concentrate once and for all on legislating.

It was the dawn of the Reagan Revolution, and the Republicans had just retaken the Senate – not an easy time to be the torchbearer for liberalism. But Kennedy assumed the role gladly. He became not only a dogged defender of the faith but also an even more adept player of the congressional game. In the ’80s, he teamed repeatedly with the unlikeliest of allies, conservative Utah Republican Orrin Hatch. It was Hatch and Kennedy who got the first major AIDS legislation passed in 1988, a $1 billion spending measure for treatment, education and research. Two years later, they pushed through the Ryan White CARE Act to assist people with HIV who lack sufficient health-care coverage. But if Kennedy knew how to play ball with the other side, he also knew how to play hardball. When Reagan tried to put Robert Bork on the Supreme Court, it was Kennedy who led the ferocious and ultimately successful liberal opposition.

Kennedy wasn’t nearly as prominent in the next major battle over a court seat, the 1991 nomination of Clarence Thomas by George H.W. Bush. Even in the best of times, Kennedy’s reputation for womanizing would have made it awkward for him to sit in judgment when Thomas was accused by Anita Hill of sexual harassment. But the Senate hearings on Thomas started at a particularly bad moment for Kennedy, just months after one of the messiest episodes in his public life. In March, while visiting the family compound in Palm Beach, Fla., Kennedy had roused his son Patrick and his nephew William Kennedy Smith out of bed so they could join him for drinks at a local bar. Smith returned to the compound that night with a young woman who would later accuse him of raping her. He was eventually acquitted after a nationally televised trial in which Kennedy was called as a witness. But the image of the capering Senator leading two younger men out to play reawakened all the old misgivings about Kennedy, women and alcohol. The man who had once been Prince Hal, the reluctant heir to the throne, was in danger of turning into Falstaff, the aging reprobate.

Kennedy pulled himself back from that brink. In the summer of the same year, a decade after his divorce from Joan, Kennedy re-encountered Victoria Reggie, a 37-year-old lawyer and gun-safety advocate who had briefly been an intern in his Senate office. Now she lived in Washington with her two children from a previous marriage. Soon they were dating, and a year later they were married. The new marriage transformed Kennedy, giving him a feeling of contentment and stability he had not enjoyed for years. It was a newly energized Kennedy who moved on to the legislative accomplishments of the ’90s, like the Family and Medical Leave Act. When the Republicans retook Congress in 1994, it was Kennedy who would push Bill Clinton from the left when Clinton’s old soul mates from the Democratic Leadership Council were urging him to move right. “The last thing this country needs,” he said then, “is two Republican Parties.”

Yet when the next President turned out to be a Republican, Kennedy still found a way to work with him on shared goals. Kennedy spearheaded the effort to pass the No Child Left Behind Act, a priority for George W. Bush. But they later parted ways over what Kennedy felt was Bush’s failure to adequately fund the program. And on other issues, there could be no common ground. In 2002, Kennedy was one of the 23 Senators who voted against authorizing the Iraq war. Years later, he would call it the “best vote” he ever cast in the Senate.

But by that time, there had been a lot of good votes – votes that left the country a changed place and a better one. Nobody talks about Camelot anymore. They struck the scenery long ago. Without Ted, the Kennedy legacy would be mostly beautiful afterglow, just mood music and high rhetoric. More than either of his brothers, he took the mythology and shaped it into something real and enduring.

On the weekend of his Inauguration in 1961, John Kennedy gave Ted, the last born of the Kennedy siblings, an engraved cigarette box. It read, “And the last shall be first.” That was almost 50 years ago. Neither of them knew then in just what ways that prophecy might turn out to be true.

We do.

Senator Edward M. Kennedy will lie in repose Thursday and Friday at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston, followed by his funeral Saturday at a city church and burial later that day near his slain brothers at Arlington National Cemetery.

Kennedy’s family plans to travel by motorcade with his body from their compound on Cape Cod, Mass., to the library in Boston on Thursday. The facility will be open to the public for certain periods on both days while Kennedy lies in repose. The Kennedys have planned a private memorial service at the library for Friday night, according to a schedule of events released by Kennedy’s Senate office.

On Saturday morning, a funeral Mass for the late senator will take place at Our Lady of Perpetual Help Basilica — commonly known as the Mission Church — in the Mission Hill neighborhood of Boston. The cavernous basilica on Tremont Street, built in the 1870s, was where Kennedy prayed daily while his daughter, Kara, successfully battled her own cancer.

“Over time, the Basilica took on special meaning for him as a place of hope and optimism,” the family statement said.

Kennedy died late Tuesday after a yearlong struggle with brain cancer. He was 77.

A burial service at Arlington was scheduled for Saturday afternoon.

Kennedy, who served in the Senate for nearly half a century, will be laid to rest near his brothers, former President John F. Kennedy and former Senator Robert F. Kennedy, on the famous Virginia hillside that serves as the burial sites of others from the storied clan, including former first lady Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis.

At the site of the eternal flame rest four Kennedy family members: the former president and his wife; their baby son, Patrick, who died after two days; and a stillborn child. Robert Kennedy’s grave is a short distance away and somewhere near it is the most likely site for Edward Kennedy’s burial.

“Senator Kennedy spent more days than most at Arlington visiting the graves of his beloved brothers and paying tribute to the fallen men and women of Massachusetts who gave their lives for our country,” the statement said.

A senior defense official said the Kennedy family some time ago approached the Army to explore the possibility of burying the senator at Arlington, the nation’s most celebrated burial ground of fallen military and the resting place of astronauts, Supreme Court justices and other giants in American history.

Kennedy is eligible for burial at Arlington by virtue of his service in Congress as well as his two years in the Army, 1951 to 1953. He was a Private First Class and served in the military police at Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe, then located in Paris and now in Belgium.

The family met with Arlington officials again Wednesday to finalize the plans, said a second defense official.

From Arlington National Cemetery, Ted Kennedy will overlook capital forever

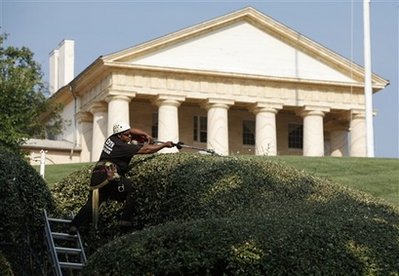

Groundskeepers marked off the hallowed lawn Thursday where Ted Kennedy will rest in perpetuity near his slain brothers at Arlington National Cemetery.

“I think he deserves to be here” said Steven Bohl, 64, of Flint, Michigan, who was among tourists checking out the site in what the Army calls the “Last Bivouac” for the brave and the good.

Bohl stopped by after visiting at Walter Reed Army Hospital with his grandson, Army Specialist 4th Class Jeffrey Adams, who lost a foot to a roadside bomb in Afghanistan last month.

“I think he was a good man. He served his country for more than 40 years,” Bohl said of Kennedy, who was in his ninth term as a senator from Massachusetts.

Tourmobiles glided by on the cemetery’s Sheridan Drive and drivers announced on loudspeakers that “Ted will be buried next to Bobby, who is next to Jack.”

The Kennedys lie near stately trees and down the steep slope from Robert E. Lee’s columned mansion. An eternal flame marks the gravesite of President John F. Kennedy. The stark white cross marking the grave of Senator Robert F. Kennedy (D-N.Y.) is a short walk to the left.

About another 50 yards to the left of Bobby’s cross is the site chosen for Senator Edward Kennedy, where the hill levels off to afford a majestic view back across the Potomac to grand monuments of the capital city.

The Army chose Sergeant Major Woody English, the Special Bugler of the U.S. Army Band who played taps at the funeral of President Ronald Reagan, to perform at Kennedy’s private graveside rites tomorrow.

“He had an interesting journey through life,” said Arlington visitor Colette Pellowski, 46, of Pleasanton, California. “He had some major ups and major downs,” she said. “When he talked, people listened. I think he had a genuine concern for people.”

Members of the U.S. Army Military District of Washington look on as Arlington Cemetery officials arrange chairs

at the burial site of Senator Edward Kennedy at Arlington National Cemetery on Thursday, August 27, 2009

Arlington National Cemetery officials and personal from the U.S. Army Military District of Washington hold a meeting at

the gravesite of Senator Edward M. Kennedy at Arlington National Cemetery on Thursday, August 27, 2009

in. Shown in the rear is Arlington House, the home of Robert E. Lee

Arlington National Cemetery officials mark the burial site of Senator Edward Kennedy at

Arlington National Cemetery on Thursday, August 27, 2009

Arlington Cemetery officials make preparations at the burial site for the late Senator Edward

Kennedy at Arlington National Cemetery Thursday, August 27, 2009

Arlington Cemetery officials gathers at the burial site as preparation are made for the funeral for

the late Senator Edward Kennedy at Arlington National Cemetery Thursday, August 27, 2009.

Members of the U.S. Army Military District of Washington and Arlington Cemetery officials rearrange chairs as

preparations are made at the burial site for the late Senator Edward Kennedy at Arlington National Cemetery Thursday, Augudt 27, 2009.

Arlington Cemetery official rearranges chairs as preparations are made at the burial site for the late Sen.

Edward Kennedy at Arlington National Cemetery Thursday, August 27, 2009.

A worker trims the hedges near the burial site of Senator. Edward M. Kennedy at Arlington National Cemetery on Thursday, August 27, 2009

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard