Jack Columbus Rittichier was born on August 17, 1933 and joined the Armed Forces while in Barberton, Ohio.

He served in the United States Coast Guard and in 10 years of service, he attained the rank of Lieutenant.

On June 9, 1968, at the age of 34, Jack Columbus Rittichier perished in the service of our country in South Vietnam, Quang Tri.

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

February 5, 2003

Release Number 02-03

Contact: (808) 541-2122

JTF-FA & CILHI RECOVERY TEAMS LOCATE POTENTIAL REMAINS OF ONLY MISSING COAST GUARDSMAN FROM VIETNAM WAR

HONOLULU, HAWAII – Missing-in-Action (MIA) search and recovery teams comprised of mostly Hawaii-based U.S. military and DoD civilian specialists including personnel from Joint Task Force-Full Accounting (JTF-FA) and the U.S. Army’s Central Identification Laboratory, Hawaii (CILHI), are currently conducting recovery operations at a crash site in Laos believed to be that of an HH-3E “Jolly Green Giant” helicopter piloted by Lieutenant Jack Rittichier, the first Coast Guard combat casualty and only Coast Guard MIA from the Vietnam War.

Rittichier, an Ohio native, arrived in Vietnam on April 3, 1968. He served with the U.S. Air Force 37th Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron in Da Nang as a volunteer exchange pilot with the Air Force.

Rittichier and Air Force crewmembers Captain Richard C. Yeend, Staff Sergeant Elmer L. Holden and Sergeant James D. Locker were shot down while attempting to rescue a downed pilot on the Ho Chi Minh Trail just inside the Laos border opposite the A Shau valley in Vietnam on June 9, 1968. The Coast Guard officially listed Rittichier as “killed in action, body not recovered.”

The recovered remains associated with Rittichier’s crash site will be repatriated to American soil in a ceremony at Hickam Air Force Base at 9 a.m. on February 14, 2003. Following the arrival ceremony, the remains will be transported to the U.S. Army’s Central Identification Laboratory where the forensic identification process will begin.

Lieutenant Jack C. Rittichier, a highly decorated Coast Guard helicopter pilot who died in Vietnam in 1968 while trying to save a downed Marine Corps pilot, was buried with full military honors on October 6, 2003, at Arlington National Cemetery.

Rittichier, the only Coast Guardsman who was missing in action, was a hero before dying in Vietnam, according to Admiral Thomas C. Collins, commandant of the Coast Guard, who delivered a eulogy.

“His record of lifesaving spans the globe, from flying relief efforts off the North Carolina coast after Hurricane Betsy to flying through blinding snow and ice conditions to rescue eight German sailors stranded on a grounded motor vessel on Lake Huron,” Collins said.

Rittichier of Barberton, Ohio, had served as an Air Force B-47 pilot before joining the Coast Guard in 1963. He helped to develop a proposal for the military pilot exchange program that would ultimately select him to serve with the Air Force in Vietnam in 1968, according to Collins.

Before going to Vietnam to fly the high-risk rescue operations, Collins said, Rittichier told his brother Dave, “The boys are over there, and this is what I do, this is what I am. I’m an air rescue pilot . . . and I’ve got an obligation to save some of them.”

In two months, assigned to the 37th Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron, he made several daring rescues of downed Army and Marine aviators.

On June 9, 1968, a Marine Corps A-4 Skyhawk went down 37 miles west of Hue. The pilot, First Lieutenant Walter R. Schmidt Jr., ejected safely but injured his leg and couldn’t move. Schmidt established radio contact with control aircraft, and a rescue attempt was coordinated, according to a Coast Guard history.

Two HH-3E “Jolly Green Giant” helicopters, including one piloted by Rittichier, were scrambled from Da Nang Air Base for a rescue attempt. Because Schmidt was injured, they would have to save him with a pararescue jumper, a dangerous maneuver that would require the big helicopter to hover in hostile territory while the jumper deployed.

One helicopter made three attempts to rescue the pilot before being driven off by heavy enemy fire and low fuel. Rittichier agreed to give it a try.

Heavy groundfire drove him away on his first attempt. After American aircraft rained more suppressive fire on the location, Rittichier tried again. As he hovered over Schmidt and the jumper prepared to deploy, enemy bullets riddled the helicopter and set it afire. Rittichier tried to land, but the helicopter crashed and exploded in a fireball. Rittichier and the three other crew members on board were killed, according to the Coast Guard history.

Subsequent attempts to rescue the injured Marine pilot were unsuccessful, and he remains missing in action.

“If we define the character of a man by his actions, Lieutenant Jack Rittichier’s conduct, under duress, endures as the quintessence of courage,” Collins said.

Joint U.S.-Vietnamese teams looked for the crash site at many locations in the 1990s without success before they found the right spot in 2002. Rittichier’s remains were excavated in January and February of this year. The excavation also recovered remains of the rest of the crew — Air Force Captain Richard C. Yeend Jr. of Mobile, Alabama; Staff Sergeant Elmer L. Holden of Oklahoma City; and Sergeant James D. Locker of Sidney, Ohio.

Rittichier, posthumously awarded the Silver Star, is one of seven Coast Guard combat deaths in the Vietnam War.

“All hands are now accounted for,” Collins said in his eulogy. “May God bless Lt. Rittichier and his family, and may God bless the United States of America.”

Courtesy of the United States Coast Guard

A Coast Guard hero: lost in Vietnam

Coast Guard file

By PA2 Patrick Montgomery, 8th District

Lieutenant Jack Rittichier was born August 17, 1933, within the 8th Coast Guard District boundaries in Akron, Ohio. As a pilot during the Vietnam War, he distinguished himself as a Coast Guard hero in life — and in death.

Rittichier was posthumously awarded the Silver Star — the third highest combat honor — for his actions in Vietnam and was the only Coast Guardsman to be classified as missing in action during the war.

Rittichier, like thousands of other servicemembers, never returned home.

The Defense Prisoner of War/Missing Persons Office in Memphis, Tenn., listed Rittichier as MIA with the classification of killed in action, body not recovered.

Rittichier was one of the first Coast Guard helicopter pilots to serve in Vietnam and the first to fall to enemy fire during the war. To many, it might be a surprise that the Coast Guard was there at all, nonetheless a Coast Guard helicopter pilot.

According to an archived Coast Guard press release, Rittichier was selected to be a part of an exchange program with the Air Force’s 37th Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron at Da Nang Air Base, Vietnam. The program called for each of the services to trade five pilots, three helicopter and two-fixed wing, to acquaint them with the other service’s tactics, techniques and activities.

For Rittichier, stationed at Coast Guard Air Station Detroit at the time, Coast Guard search and rescue missions were something he did well.

In June 1967, Rittichier was awarded the Air Medal for his role as co-pilot during a rescue on Lake Huron. He and the crew flew 150 miles in blinding snow and sleet to rescue eight men stranded on the grounded West German motor vessel Nordmeer. On scene, Rittichier assisted in transferring the stranded men to safety aboard the CGC Mackinaw.

The Coast Guard also awarded Rittichier with a Unit Commendation Award for his rescue work during the Hurricane Betsy relief effort while attached to Coast Guard Air Station Elizabeth City, North Carolina.

Calling on the piloting skills that helped him make it through difficult conditions such as sleet, snow, heavy rains and even hurricane conditions, Rittichier left the United States for Vietnam and the challenging duties ahead.

The view passing below Rittichier in Vietnam was much different from what he was accustomed to behind the stick of a helicopter. Instead of flying over the familiar blue lakes and oceans of his home country, he now found himself above the harsh jungle terrain and mountains of Southeast Asia.

Information provided by the Coast Guard Historian’s Office cites examples of heroism Rittichier performed within weeks of his arrival at the war front.

Soon after arriving in Da Nang, Vietnam, Rittichier was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross after serving as co-pilot for a mission that resulted in saving four crewmembers from a downed U.S. Army helicopter. They were trapped by hostile ground fire.

Less than a month later, he earned a second Distinguished Flying Cross. In the pilot’s seat this time as rescue commander, Rittichier managed to maneuver his helicopter, guided by the light of illumination flares, into a narrow opening surrounded by trees and a mountain slope to rescue nine survivors of another downed helicopter.

It was on June 9, 1968 — two months and a day after arriving in Vietnam — that Rittichier made his last rescue attempt. The archived Coast Guard press release, a biography prepared by the historian’s office and Rittichier’s citation for the Silver Star paint a picture of Rittichier’s final mission.

It began with a Marine Corps fighter pilot ejecting from his aircraft and parachuting into a temporary North Vietnamese soldier’s camp. The pilot, suffering from a broken arm and leg as a result of the fall, was used by North Vietnamese soldiers as human bait to draw rescue helicopters within killing range of their gunfire and air strikes.

One rescue helicopter, intent on retrieving the pilot, had already made three unsuccessful attempts to break through the enemy fire to rescue him before being forced to break off to refuel. Rittichier, piloting a second rescue helicopter, took over and made his attempt at picking up the injured pilot.

Heavy enemy fire forced him to break off before he could reach the grounded Marine. Other helicopters laid down suppressive fire to clear the area of North Vietnamese troops.

In spite of the heavy resistance, Rittichier once again dove in to save his fellow countryman. While he was maneuvering the helicopter into a hover above the downed pilot and beginning the actual rescue, heavy North Vietnamese ground fire struck his aircraft.

Rittichier tried to pull the helicopter back to safety, but it was damaged too heavily by the North Vietnamese attack.

According to eyewitness reports, his aircraft caught fire while still in the air, touched down on the ground soon after, and exploded. Other helicopters in the area flying over the burning wreckage reported no survivors.

Rittichier was survived by his parents and his wife, Carol Ann.

Rittichier was one of seven Coast Guard combat deaths during the Vietnam War. For his actions, Rittichier was posthumously awarded the Silver Star. His citation for the Silver Star reads:

“Lieutenant Jack C. Rittichier, United States Coast Guard, distinguished himself by gallantry in connection with military operations against an opposing armed force as rescue crew commander of an HH-3E helicopter in Southeast Asia on 9 June 1968. On that date, Lieutenant Rittichier attempted the rescue of a downed pilot from one of the most heavily defended areas in Southeast Asia. Despite intense accurate hostile fire, which had severely damaged another helicopter, Lieutenant Rittichier, with undaunted determination, indomitable courage and professional skill, established a hover and persisted in the rescue attempt until his aircraft was downed by hostile fire. By his gallantry and devotion to duty, Lieutenant Rittichier reflected great credit upon himself and the United States Coast Guard.”

Subject: a hero to be laid to rest

E-Mail Received On 23 August 2003

On 6 October, 2003, at 1300 hours, the remains of United States Coast Guard Lieutenant Jack Columbus Rittichier will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Jack was the first Coast Guardsman killed in action in Vietnam, and the only one who remained unaccounted for after the war’s end.

The crash site of the Jolly Green 23 was discovered on 9 November 2002, and the remains of the four crew members were repatriated on 14 February 2003; positive ID was confirmed to Rittichier’s brother (Dave) on 11 August 2003.

Maggie and Dave Rittichier are allowing the funeral to be an open one, and would very much like to see a large crowd present. If you are able to make it, please attend the funeral. Jack will be buried at Coast Guard Hill, in an area normally reserved for the top officials; a Commandant gave up his spot for Jack.

Information about and photos of Jack can be found at the URL below. If you would like to e-mail Dave and Maggie, contact me at snj@faraway-soclose.org and I will send you their address.

http://www.faraway-soclose.org/jcr/

27 August 2003

Although no body had been recovered, Dave Rittichier of Erwin long ago resigned himself to the fact that his brother Jack had died during a rescue mission in Vietnam.

Dave, who earlier this year had provided blood samples for use in DNA testing, received word last week that remains found in the jungles of Southeast Asia had been identified as Jack’s.

Now, plans are under way to lay to rest the former helicopter pilot – one of the most heralded heroes in U.S. Coast Guard history – among the elite at Arlington National Cemetery. He will be buried in a special section of the cemetery known as Coast Guard Hill.

Dave said he learned of lab findings identifying his brother in a phone call from Lt. Cmdr. James Brewster, who is assigned to Coast Guard headquarters in Washington, D.C.

Instead of being disheartened, Dave said: “Actually, I was thrilled at hearing the results of the testing, and I’m satisfied that we finally will get closure.

“I’m proud that Jack died trying to save a comrade. I’ve had his scrapbook to remember him by, but now I’ll have somewhere to go to visit him at his grave.”

Jack Rittichier, who grew up with younger brother Dave in Portage Lakes, Ohio, was among a group of Coast Guard helicopter pilots who volunteered to serve with

the U.S. Air Force in Vietnam as part of an exchange program.

Before entering the program, he had established a record of heroism, including earning an Air Medal for rescuing eight stranded men on a German vessel during a snowstorm on Lake Huron.

Upon his arrival in Vietnam, Jack quickly earned two Distinguished Flying Crosses for his bravery during rescue missions.

On June 9, 1968, Rittichier and his crew of three were trying to rescue a downed Marine Corps fighter pilot when they came under heavy fire. According to eyewitness accounts, their helicopter erupted in flames and settled to the ground before exploding.

The exact location of the tragedy – which occurred about 37 miles west of the Vietnamese city of Hue — remained a mystery until late last year. In the absence

of a body, Rittichier’s name had been listed through the decades among the nearly 2,000 Americans unaccounted for in the war.

Dave Rittichier and his wife, Maggie, received correspondence from the military for several years before learning last fall that the site apparently had been found.

Remains believed to be those of Jack and the three Air Force crew members were flown in February to Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii and taken to the U.S. Army

Central Identification Laboratory for intensive testing.

To assist in the process, Dave provided blood samples for use in possible DNA matches with the remains found in Vietnam.

Brewster, who until recently served as a Coast Guard decedent affairs officer, told The Erwin Record last week that although no official documentation has been

released by the lab, everyone he has spoken to has led him to believe that the remains of all four men have been identified.

Brewster added that although his primary duties have changed, he will continue as project director until Jack Rittichier has been buried with proper honors.

Rittichier was the first member of the Coast Guard and its only flier to have died in the Vietnam War. Hundreds – maybe even thousands — of Americans have worn

POW/MIA bracelets bearing his name, Coast Guard buildings have been named in his honor, and Web sites have been created to perpetuate his memory.

Brewster explained that a monument originally was placed on Coast Guard Hill at Arlington to honor members of that branch of the service who died in World War I. Since that time, however, the hill has become what he described as a “VIP spot.”

The limited space on the hill is reserved for graves of the most prominent members of the Coast Guard, such as its commandants.

The current commandant, Adm. Tom Collins, reportedly sent down word recently that Rittichier should be buried there even if it meant using the gravesite intended for Collins himself.

“All kinds of people, including members of the POW/MIA groups from throughout the nation, have followed the story for years,” Brewster said. “Many of them probably will want to attend the funeral.”

Brewster added that the Coast Guard may attempt to identify and notify those who have worn the Jack Rittichier bracelets.

Exactly when family members and others will be attending ceremonies and a funeral is open to speculation, especially since the lab still hasn’t officially told anyone that the remains have been identified.

However, Brewster said he has been planning for alternate funeral scenarios since he began to hear through the grapevine about two months ago that

identification had been made.

He said Rittichier probably was identified through dental records, with DNA test results providing additional evidence.

Maggie Rittichier, who moved here with her husband about seven years ago, has handled much of the correspondence with the military. She said the family has decided that October probably would be the best time for the ceremonies at Arlington.

When Brewster called the Rittichiers, one of the reasons was to learn if family members would prefer a burial at the national cemetery. Another option would be

a cemetery elsewhere, such as the one in Akron, Ohio, where Dave and Jack’s parents are buried.

Dave said he, younger brother Henry and Jack’s widow, Carol, agreed that Arlington was clearly the most appropriate place.

“It’s a tremendous honor for him to be buried with the other Coast Guardsmen there,” Dave said.

According to Brewster, graveside services will be just one of several related events he will help arrange.

A military ceremony will be conducted before Coast Guard aviators depart from Hawaii to fly Jack Rittichier’s remains to Washington, where another ceremony will

be held upon arrival.

Brewster said that, depending upon the family’s wishes, a funeral service may be held at a public place before the graveside rites on Coast Guard Hill.

“I’m looking forward personally to helping lay to rest a genuine Coast Guard hero,” Brewster said.

October 7, 2003

Family says goodbye to Coast Guard pilot

Vietnam MIA home at long last

By JANETTE RODRIGUES

Courtesy of Houston Chronicle

Not a day goes by when Houstonian Henry Rittichier doesn’t think about his brother Jack, the only U.S. Coast Guardsman declared missing in action in Vietnam.

Rittichier was 25 when two Coast Guardsmen came to his parents’ door in Barberton, Ohio, to tell them the HH-3E “Jolly Green Giant” helicopter piloted by Lieutenant Jack C. Rittichier, 34, had been shot down during a rescue mission in June 1968.

“I was preparing a meal with my wife,” Rittichier recalled Tuesday from Washington, D.C. “I thought a mistake was made.”

On Monday, he and his family stood beside his brother’s flag-draped casket at Arlington National Cemetery’s Coast Guard Hill. The hill overlooks the Pentagon, a part of the cemetery usually reserved for senior officers.

“There is not a word in the dictionary to describe what happened yesterday,” Rittichier said of the ceremony. “You would have to put a number of words together – awe-inspiring, relief, incredible, sad.”

Since his brother went on that final mission to rescue a U.S. pilot trapped behind enemy lines with a broken leg, Rittichier moved to Texas in 1975 to work at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, raised a family, divorced and started a manufacturing business.

While he gave up the dream his brother was still alive, the retired senior scientific instrument maker held on to his hopes he would be found.

“I prayed every day,” Rittichier said. “They gave us the news this year he had been brought back to Hawaii for identification.”

It was, he said, like going back to that day in 1968 when they learned his brother and his three-man Air Force crew were downed and their remains could not be recovered.

In May 2002, U.S. officials received information about a crash in Laos, about nine miles from where Rittichier’s helicopter was seen going down. The U.S. Army Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii identified the remains recovered from the wreckage as those of Rittichier and his crew.

Homeland Security Secretary Tom Ridge was among those who attended Rittichier’s funeral. Six white horses then pulled the casket on a black caisson during a half-mile procession to the grave site.

During a reception later, Henry Rittichier was humbled when several women gave him MIA bracelets inscribed with his brother’s name.

“He was a role model for me; he was 9 years older than I was,” Rittichier said. “I was in awe of him; he was my hero.”

Jack Rittichier grew up to become captain of the 1955 Kent State University football team and fly bombers for the Air Force and helicopters on search-and-rescue missions for the Coast Guard.

During a military career that started with the Air Force and ended with the Coast Guard Reserve, he was awarded three Distinguished Flying Cross Medals and four Air Medals. He was posthumously awarded the Silver Star and Purple Heart.

The Coast Guard Web site said Rittichier received one of the Air Medals in 1967 as co-pilot during a dangerous snowstorm to save the crew of the Nordmeer, a West German vessel grounded on a shoal in Lake Huron. Soon after the eight crewmen were saved, the Nordmeer broke apart and sank.

Two weeks after he arrived in Vietnam as part of a Coast Guard-Air Force aviator exchange program, he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for flying through heavy enemy fire to save four Army fliers.

Other rescue missions, and medals, followed.

Henry Rittichier, now 60, is still devastated by Monday’s ceremony and the outpouring of love from family members he hasn’t seen for 30 years and strangers who have created Web sites dedicated to his brother.

In 2001, Rittichier lost a number of family heirlooms to Tropical Storm Allison’s floodwaters, including some precious keepsakes connected to his brother.

“I have some photos of him and his official Coast Guard cuff links,” Rittichier said. Everything else of his brother was ruined.

Now, he has the MIA bracelets and memories of a seven-member rifle party firing a three-volley salute, a Coast Guard helicopter fly-by and a bugler playing taps for the brother who was his “hero on earth.”

7 October 2003

Molly Kavanaugh

Plain Dealer Reporter

Washington, D.C.- Atop a small hill at Arlington National Cemetery, a missing hero was laid to rest yesterday.

U.S. Coast Guard Lieutenant Jack Rittichier, a pilot, volunteered to go to Vietnam because “this is what I do, this is what I am,” Admiral Thomas Collins said in the eulogy of the service, attended by nearly 600 people. “He is the quintessence of courage.”

For 35 years, Rittichier was missing in action in the jungles of Vietnam after trying to rescue a downed Marine helicopter pilot on June 9, 1968. But many already knew of the heroism of this 34-year-old man from Barberton, the Coast Guard’s only MIA.

Yesterday, with Rittichier’s re mains finally returned to U.S. soil, his extended family united to celebrate his life.

Stacey Jones became so impressed by what she learned about Rittichier that the 26-year-old woman from Arkansas developed a Web site in his honor and wore his MIA bracelet. She slipped the bracelet off her wrist and presented it to a family member at a reception following the interment.

Two others wearing bracelets did the same thing, and dozens more bracelets are being mailed in for the family.

A Naval Sea Cadet unit in New Jersey adopted Rittichier’s name for its training ship, or unit.

“He risked his life for other people,” said 13-year-old Sarah Holderer, who marched with 18 other youths at Andrews Air Force Base, where Ritti chier’s remains were brought from the forensic laboratory in Hawaii.

Although DNA samples were collected from his family, Rittichier’s identification could be made from just his dental records.

A college professor – a former classmate of Rittichier’s at Kent State University – taught his students about heroism using Rittichier as a model.

“He believed in public service. It’s carved into my mind what he stood for,” said Bernard Reiner, tears forming in his eyes as he walked behind the horse-drawn carriage carrying Rittichier’s casket.

In a final tribute, four helicopters flew over the flag-draped casket.

Meanwhile yesterday, at thousands of Coast Guard stations and on cutters across the country, the American flag was flown at half- mast.

Rittichier’s portrait is being added to the Coast Guard’s Hall of Heroes in Washington.

Rittichier’s brother, Dave, said he knows what his brother would say to all this talk about heroism.

“I’m not a hero. I’m just doing a job I was trained for. I answered the call,” said Dave Rittichier, sitting at the grave site after the service.

Before going to Vietnam, Rittichier flew search-and-rescue operations on the Great Lakes.

Rittichier was awarded the Air Medal for rescuing eight men from a grounded freighter in a blinding snow and ice storm on Lake Huron.

He proposed the idea of having an exchange pilot program with the U.S. Air Force, then volunteered to go to Vietnam.

Rittichier’s mother, Ruby, now deceased, pleaded with him to reconsider, then urged Dave to talk him out of it.

“It’s what I have to do,” Rittichier told his family, and Carol, his wife of 11 years.

In two months, he earned two Distinguished Flying Crosses, one for maneuvering his chopper into a narrow opening surrounded by trees and a mountain slope to reach nine servicemen.

His death devastated his wife. For comfort, she turned to a tape recording of his voice. “I used to play that tape by the hour just to hear his voice. I hugged his clothes,” she said.

Two years later, she met another Coast Guard pilot, John Wypick, and they were married. “I am so blessed to love and be loved by two fantastic men,” said the 65-year-old woman, now living in California.

But she always wondered about her first husband’s final resting spot.

The Wypicks talked about visiting what was once the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Now they don’t have to.

Investigative teams from the Joint Task Force-Full Accounting, using location information from eyewitnesses, began working in 12-foot-high elephant grass in November 2002.

Petty Officer Lauren Smith visited the site in January, and yesterday, she came from Boston to tell the family firsthand what she saw.

“The greenery has grown back and the villages are peaceful, but you can still see what was left behind,” she said, describing hills dotted with craters.

The bodies of Rittichier’s crew, three Air Force servicemen, also were recovered. Capt. Richard Yeend was buried September 28 in Mobile, Alabama, Staff Sgt. Elmer Holden will be buried next week in Hampton, South Carolina, and Sergeant James Locker will be buried October 18 in Sidney, Ohio.

Doug McGill, who will give the eulogy at Locker’s funeral, helped the men prepare supplies for their last mission.

“The crew knew the risk was very, very high, yet none hesitated to board that bird and go save another human life. They were waving and smiling as they left,” he said.

McGill could not attend yesterday’s ceremony, but Bob DuBois, a retired Air Force pilot, came. He was the last person to speak to Rittichier.

DuBois was flying in another helicopter, helping to direct Rittichier to the downed pilot who was surrounded by heavy enemy ground fire.

DuBois radioed Rittichier that his chopper was on fire, so Rittichier turned off the damaged engine to stop the fire and, with one engine left, told DuBois he was going to try to reach a nearby clearing.

Before he could land, the rotors stopped and the chopper fell to the ground, exploding like a can of napalm, DuBois said.

“Another 20 seconds, he would have been on the ground and we would have picked them up,” DuBois said.

The soldiers never found Walter Schmidt, the Marine pilot the men were trying to rescue.

The New Yorker is one of nearly 1,900 men and women still missing from the Vietnam War.

For the Coast Guard, which lost seven men in Vietnam, the missing designation is no more. Said Collins: “All hands are now accounted for.”

Coast Guardsman, Vietnam MIA Remembered

Mon Oct 6, 2003

The only U.S. Coast Guardsman who was declared missing in the Vietnam War was remembered Monday as a hero, some 35 years after he and three others were killed while trying to rescue another serviceman.

That was the last of many rescue attempts made by Lieutenant Jack C. Rittichier of Barberton, Ohio, who was known to his friends and family as a man who could do everything.

“I know just what he would have said if he were here today: `I’m no hero. It’s my job,'” said younger brother David Rittichier, 69, of Erwin, Tennessee.

Rittichier, who was 34 at the time, was the pilot of an HH-3E helicopter that had left Da Nang Air Base in South Vietnam on June 9, 1968, on a rescue mission for a downed U.S. pilot. His helicopter was struck by enemy fire and exploded in a fireball.

The pilot Rittichier was trying to rescue, Marine First Lieutenant Walter R. Schmidt, of Nassau, New York, had been shot down and was stranded in enemy territory with a broken leg. Schmidt didn’t survive and was listed as MIA.

Before Vietnam, Rittichier won honors for rescue work during Hurricane Betsy in 1965. He also earned an Air Medal in 1967 for copiloting a helicopter that rescued eight seamen from a West German vessel in Lake Huron.

Rittichier was discharged from the Air Force as a captain in 1963. He then joined the Coast Guard and volunteered for a pilot exchange program in Vietnam.

Two weeks after being deployed, he earned his first Distinguished Flying Cross for flying through enemy fire to save four Army soldiers. He would earn two additional Flying Crosses and three more Air Medals before his last flight.

“If we define the character of a man by his actions, Lieutenant Jack C. Rittichier is the embodiment of courage,” said Admiral Thomas Collins, the Coast Guard Commandant.

Homeland Security Secretary Tom Ridge also attended the funeral, which was followed by a half-mile procession behind Rittichier’s flag-covered casket. It was pulled by six white horses on a black caisson to his grave site at Arlington National Cemetery’s Coast Guard Hill overlooking the Pentagon, a part of the cemetery usually reserved for senior officers.

Mourners recited The Lord’s Prayer, then a seven-member rifle party fired three volleys. As a lone bugler played taps, four red and white helicopters circled the hill, representing every type of chopper in the Coast Guard inventory.

“When those guns went off and those helicopters went over … I was flooded with a lot of the old feelings,” David Rittichier said of his older brother, who played football in high school and was captain of the 1955 Kent State University Golden Flashes. “We’ve missed him terribly.”

A Coast Guard bagpipe band played “Amazing Grace” as Collins presented a flag to David Rittichier. Brother Henry Rittichier, 60, of Houston, and Rittichier’s widow, Carol Wypick of Fountain Valley, California, said they had waited a long time.

“I never thought this day would come,” said Wypick, who later married another Coast Guard search and rescue pilot. “You have no idea, in my heart, how wonderful this is.”

Joint U.S.-Vietnamese teams searched for the crash site in Vietnam, but came up empty each time. In May 2002, officials received information about a crash near Ban Kaboui, Laos, about nine miles from the reported loss location. The U.S. Army Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii identified the remains recovered at the wreckage as those of the pilots and crew.

Also killed in the Vietnam mission were: Rittichier’s co-pilot, Air Force Captain Richard C. Yeend Jr. of Mobile, Alabama; and two crew members, Air Force Sergeant James D. Locker of Sidney, Ohio, and Air Force Staff Sergeant Elmer L. Holden of Oklahoma City.

At a reception following the funeral, three people who wore MIA bracelets engraved with Rittichier’s name gave their bracelets to the family.

“I’ve worn this bracelet with pride and hope,” said Deborah Eggleston of Newcomerstown, Ohio. “This man fought for my freedom. He was already a hero in my eyes.”

RITTICHIER, JACK COLUMBUS

- LT US COAST GUARD

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: 09/08/1963 – 06/09/1968

- DATE OF BIRTH: 08/17/1933

- DATE OF DEATH: 06/09/1968

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 10/06/2003

- BURIED AT: SECTION 4 SITE 3214-A

Carol Wypick, widow of Lt. Jack Columbus Rittichier, whose remains were found in Vietnam in 2001,

and laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery, cries on the shoulder of her husband, John Wypick,

during the funeral. Rittichier , along with three other helicopter crew members, died after being shot down

while attempting to rescue a U.S. Marine.

Dave Rittichier, right, puts his hand on his heart as the casket of his brother, Coast Guard

Lieutenant Jack C. Rittichier, is carried to graveside at Arlington National Cemetery, Monday,

October 6, 2003. Left of Dave is his wife, Maggie Rittichier, and Lieutenant Rittichier’s

widow, Carol Wypick. The remains of Lieutenant Rittichier, the only Coast Guardsman who

was missing in action from the Vietnam War, were recently identified and returned to the U.S.

U.S. Coast Guard Commandant Thomas H. Collins (R) presents the American flag to David Rittichier,

brother of Lieutenant Jack Columbus Rittichier, whose remains laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery, October 6, 2003.

David Rittichier, the brother of Lieutenant Jack Columbus Rittichier (R), grieves with his wife Maggie

at the gravesite of his brother after he was laid to rest, at Arlington National Cemetery, October 6, 2003.

Carol Wypick (R) observes funeral services with full military honors for her former husband, United States

Coast Guard Lieutenant Jack C. Rittichier of Barberton, Ohio, the only Coast Guardsman who was missing in

action from the Vietnam War, as he is laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery.

United States Coast Guard Lieutenant Jack C. Rittichier, of Barberton, Ohio, the only Coast Guardsman

who was missing in action from the Vietnam War, is laid to rest as family members look on at Arlington National Cemetery

A lone Coast Guardsmen salutes during funeral services with full military honors for

Leiutenant Jack C. Rittichier, United States Coast Guard, of Barberton, Ohio, the only Coast Guard member

who was missing in action from the Vietnam War, at Arlington National Cemetery

Dave Rittichier, brother of Coast Guard Lt. Jack C. Rittichier, the only Coast Guardsman who was missing in

action from the Vietnam War, pauses at his casket after his funeral services at Arlington National Cemetery

Dave Rittichier mourns at his brothers casket at Arlington National Cemetery, October 6, 2003

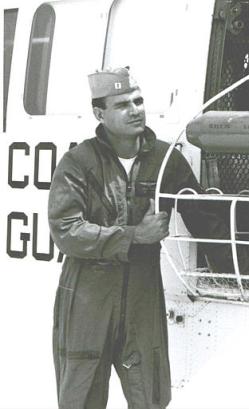

Undated black-and-white file photo of Lt. Jack Rittichier prior to his deployment to Vietnam

Remains of Coast Guardsman with Danbury Twp. ties identified

By RICK NEALE

Staff writer

DANBURY TOWNSHIP — The first U.S. Coast Guardsman killed in the Vietnam War is heading back home, to the relief of Danbury Township resident Pat Lattimore.

Lieutenant Jack C. Rittichier, a Barberton resident, died in an explosion in June 1968 when his HH-3E Jolly Green Giant rescue helicopter crashed in Laos. He was also the last Coast Guardsman listed as missing in action in Vietnam — for a span of 35 years — until military archaeologists excavated and identified his remains in February.

Rittichier will finally be buried Monday during a solemn ceremony in Arlington National Cemetery. Attending will be Lattimore, who remembers her brother-in-law with pride.

“Oh, Jack was fantastic,” Lattimore said. “Jack was a wonderful teacher — anybody could learn from Jack.

“He was respected and loved by everyone who knew him. He was dedicated to saving lives. That was his No. 1 mission in life. He was really a nice guy.”

Lattimore and her husband planned to leave this afternoon to meet relatives from around the nation in Washington, D.C. She said the chapel in Arlington holds up to 250 people — and 500 have already registered to attend Monday’s event.

“I know it’s going to be wonderful,” she said.

Marblehead Coast Guard personnel will observe a moment of silence Monday and lower the station flag to half-mast — a ritual that will be performed at every Coast Guard station in the United States.

A similar Vietnam homecoming happened in May in Port Clinton for Arthur “Charlie” Buck, who was killed in action in January 1968. The U.S. Navy Reserves lieutenant bombardier died when his OP-2E Neptune patrol plane plowed into the side of a mountain in Laos.

The crash site wasn’t discovered until 1996, and Buck’s remains were finally identified in December at a Hawaii military laboratory. He was buried in Lakeview Cemetery.

Rittichier played quarterback on the Kent State University football team and was a national trampoline champion. He logged five years in the U.S. Air Force and worked as a cropduster before volunteering for Coast Guard duty in Vietnam.

On his doomed search and rescue mission, the helicopter he was piloting was hit by enemy fire, then stalled, crashed to earth and exploded. The crash site remained undiscovered for years — leaving a raw, painful wound for his family, Lattimore said.

“His mother and father (Ruby and Carl Rittichier) were killed in a car accident in the 1970s. His mother was always sure that Jack was going to call on the phone and say, ‘Hey, I’m coming home,’ or that he was wandering around in the jungle someplace,” she said.

In May 2002, U.S.-Vietnamese search parties enlisted in the Joint Task Force-Full Accounting effort pinpointed the crash site near Ban Kaboui, Laos.

Rittichier’s remains were discovered with those of three other airmen. One was from Sidney, Ohio.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard