INDO-CHINA REBELS KILL U.S. OFFICER

Slay Lieutenant Colonel A. Peter Dewey From Ambush

British Arrest Commander of Japanese

SAIGON, French Indo China, September 26, 1945 Lieutenant Colonel A. Peter Dewey of Washington, D.C. was killed and Captain Joseph Coolidge of New Hampshire was seriously wounded by Annamese in disorders today.

Other American officers, defending United States headquarters from a siege of three hours, killed at least eight natives.

British, French and Japanese also suffered casualties in a series of incidents. As a result of the continued disorders, Field Marshall Count Juichi Terauchi, the Japanese commander, was placed under house arrest.

Colonel Dewey was the senior American officer for the Office of Strategic Services in Saigon and was returning from a visit to Captain Coolidge in a nearby hospital to his headquarters in a suburban mansion when he was killed.

He was driving a jeep with Major Herbert Bluechel, former movie chain operator of San Francisco and San Anselmo, California. Major Bluechel told of the tragedy:

“We were returning to the O.S.S. hostel when we passed through a partial double roadblock. As we drive through, Annamese in a ditch beside the road opened with a machine gun not ten yards away. The charge caught Peter in the head.”

“The jeep overturned in the ditch. I saw Peter was dead and I couldn’t help him, so I crawled from under the jeep. While the Annamese still were firing, I crawled along a hedge for 150 yards, firing my .45 back at them, slowing them down. When I reached the house I alerted the other offices and we broke out the arsenal. The Annamese besieged the house for about three hours until British Gurkha troops arrived. The natives had cut our telephone wires and I had to radio O.S.S. headquarters in Kandy, Ceylon, who radioed the British in Saigon to send help.”

Captain Coolidge was shot through the stomach and an arm while returning from Dalat, seventy miles north of Saigon, with a four-car British party. Escorting Japanese troops refused to fire at the Annamese and a Japanese officer refused to order them to fire.

Finally, forty Japanese who had been summoned by a Japanese bystander arrived and halted the shooting, but took no action against the Annamese.

The incidents were the first involving American forced in Indo-China, although widespread disorders against the French have been reported throughout the Kingdom of Annam where a nationalistic group – the Vietnam – has rebelled against the return of French rule. The Vietnam with Japanese approval announced the independence of Annam last March.

Vietnam guerrillas cut roads from Saigon to the airfield Tuesday, attacked British power stations and occupied some suburbs. An Annamese leader said then that the Vietnam planned no violence but intended starving out the European population by cutting off food supplies.

There was still no electricity or water in the city and the people appeared panicky because of the deterioration of the food situation.

The British Chief of Staff under Lieutenant General Douglas d. Gracey has divided Saigon into two command areas for control purposes and flew in 300 more Gurkha troops.

Colonel Dewey’s father, former Representative Charles Dewey of Illinois, said that his son had served with both the Polish and American armies in World War II and had won a decoration for having organized the French underground in southern France.

Stationed in Paris at the outbreak of the war as a correspondent from the Chicago Daily News, Colonel Dewey enlisted in the Polish army as a Lieutenant. Following the fall of France, he escaped through Spain to Portugal, where he was placed in an internment camp.

Later he was released and returned to this country where he enlisted and served as an intelligence officer with the Air Transport Command in Africa. Transferring to the OSS, he rose to the Captaincy of a paratroop unit and parachuted into southern France five days before the American invasion to organize the underground.

Colonel Dewey was education at St. Paul’s School in Concord, New Hampshire, in Switzerland and at Yale University.

Update on entry for A. Peter Dewey

He is listed on the ABMC {American Battlefield Monument Commission}

website on Tablets of the Missing at Manila National Cemetery. (Reference only}

Name: Albert P. Dewey

Rank: Major, US Army

No# : Service 0-911947

United States Office of Strategic Services

Entered the service from State: Illinois

Died 26 Sept 1945

Awards listed:

Silver Star

Legion of Merit with Oak Leaf Cluster

French Croix de Guerre

French Legion of Honor Chevalier

Tunsian Order of Nicham-el-Oftikhar

Maj. Peter Dewey, America’s First Vietnam Casualty

U. S. Adolph

6 September 2005

Like the last, the first U.S. casualty in Vietnam is shrouded in controversy, mystery and political intrigue. Even the statement “the first,” like “the last,” is open to question. You won’t find his name on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, nor will it appear on any Missing in Action list, even though his body was never recovered.

However, there is little doubt that Major A. Peter Dewey was the first American soldier to be struck down by Communist bullets in what would later become America’s longest and most controversial war.

Dewey’s main purpose when he arrived in Saigon on the 4th September 1945 was to arrange for the repatriation and evacuation of U.S. POWs being held there by the Japanese. When he landed at Tan Son Nhut Airport on that first day of what were to be the last three weeks of his life, American fighting men had been involved in an air and naval war with the Japanese in the skies and water of Indochina for nearly three years. Even the harbour of Saigon had been raided and bombed by U.S. carrier based aircraft.

The OSS team that Major Dewey headed, code name Project EM BANKMENT, was to locate 214 Americans at two Japanese camps in Saigon. The majority of them had been held in Burma for most of the war and employed, as slave labour building a railroad line that was to cross the Kwai River, later made famous by the movie Bridge On The River Kwai.

Camp Poet in Saigon held five POWs, and Camp 5-E, just outside of Saigon, contained 209. Of these, 120 were from the 2nd Battalion, 131st Field Artillery of the 36th Division, a National Guard antiaircraft outfit from Texas that had landed in Java by mistake and had been captured intact. They would later become known as the “Lost Battalion.” Of the remaining POWs, 86 were survivors of the cruiser Houston, sunk on the night of 28-29th February 1942 off the coast of Java. Their fate was also unknown until Dewey liberated them. The other eight were airmen shot down over Indochina.

Peter Dewey was born in 1916 in Chicago, had been educated in Switzerland, St. Paul’s School (London), Yale (where he studied French history) and Virginia Law, and head worked as a journalist in the Paris office of the Chicago Daily News. While reporting on the German invasion of France for his paper, Dewey decided to become more directly in volved. In May 1940, during the Battle of France, he enlisted as a lieutenant in the Polish Military Ambulance Corps with the Polish army then fighting in France.

This was somewhat to be expected for his father, Charles S. Dewey, who was a conservative, anti-New Deal isolationist and former Republican congressman from Illinois, had at one time been an international banker with the Northern Trust Company of Chicago as a financial advisor to the Polish government. After World War I, he had played an important part in the establishment of the modern Polish fiscal system.

After the Petain government capitulated, Dewey somehow escaped to Portugal through Spain where he was placed in an internment camp. Later, when he was released, he returned to the U.S. and wrote a book entitled, As They Were, about the French defeat. Not able to stay away from the action for long, he then joined Nelson Rockefeller’s Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs as that agency’s liaison to de Gaulle’s Free French.

In August 1942, Dewey entered the U.S. Army as a lieutenant and served as an intelligence officer with the Air Transport Command in Africa. Finding that he had been rejected as “unsuitable” in a request to transfer to OSS, he took his case to the head of that organization, an old family friend, General Bill Donovan. After his second try was successful, he lad a parachute team of three Americans and seven Frenchmen in August 1944 in to South Western France. The operation, named ETOILE, was to provide coordination between the Allied commander of the invasion of southern France (DRAGOON) and the left-wing maquisards along the Spanish Republican frontier. These forces, it was known, were under Spanish Republican command and were planning for an invasion of Franco Spain as soon as the Germans left. In circumstances that Dewey would find repeated in Saigon, the political delicacy of the task was compounded by the many different organizations of the region oriented in every which direction. There was even some concern that the Gaullist Etoile mission would be in as much danger from “friendly” forces as from the Wehrmacht.

With Dewey in the B-17 that departed on 10th August 1944 from Blida Airport outside Algiers, was Jack Hemingway, son of Ernest Hemingway. In what must be considered on of the oddities of gear ever taken on a combat operation behind enemy lines, Jack jumped with his trout rod strapped to his leg. However, considering the terrain that they parachuted in to (a thirty mile wilderness at the headwaters of the Loire) perhaps the fishing gear was intended for survival.

At the beginning, the operation started of badly. Dewey and his group landed over 20 miles from their intended destination. Then the linkup with the second drop (consisting of the French contingent for the operation) was not completed until five days later. The linkup problems were compounded by the Gaullist team losing their radio during the jump. It was only after they had “borrowed” a radio from local peasants and arranged for an emergency re-supply that the entire team go together.

By now it was 15th August, DRAGOON D-day, and Dewey was to learn that his original mission had been changed due to the undreamed success of the invasion assault ashore. His task now was to concentrate on intelligence gathering on the left flank of the DRAGOON forces in their movement up the Rhone Valley toward the southern German border.

Dewey, with the help of the maquis, was able to find the headquarters of the Corps Franc de la Montagne Noire. As a result, Mission Estoile’s first intelligence report was also one of its most important: Information on the details of the Wehrmacht’s withdrawal was immediately transmitted to the invasion fleet. U.S. carrier based Hellcat fighter-bombers were able to intercept these forces with devastating results. It was also learned that the Germans would not stand in the French Alps as had been expected, but on the German Rhine.

Soon afterwards, Dewey’s team began a 600-mile journey through enemy territory in what was to become an OSS legend. Travelling in two captured German Volkswagen staff cars with an escort of maquisards, they sent back valuable intelligence as well as destroying two German Mark III tanks and capturing one (it was given to the maquis to use) along with nearly 400 German prisoners. It was also one of Dewey’s reconnaissance teams that replaced the American Flag after its several years in absence on the American Embassy in the capital of the French New Order, Vichy.

On the 5th September, Dewey and his team met Donovan at Seventh Army forward headquarters. Dewey was greeted with the promise that he would be made a lieutenant colonel, a promise that was to be kept shortly after his death just over a year later.

Returning to Washington in October, Dewey worked on the OSS history project under the direction of New Yorker columnist Geoffrey Hellman. In July 1945, he was selected to head up the OSS team that would enter Saigon after the Japanese surrender. But difficulties arose when British Major General Douglas D. Gracey, commander of occupation forces in Indochina south of the sixteenth parallel (the Potsdam Conference split the reoccupation of Indochina between the British and the Chinese) objected to an American presence and sought to bar their participation. However, Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten intervened, and Dewey’s team of OSS men was allowed to leave Ceylon for Saigon on the 1st September.

Preceding Dewey was an advance element of Embankment, a prisoner of war evacuation team that was parachuted in to Saigon. After stops at Rangoon and Bangkok, Dewey and the remaining members of his team landed at Tan Son Nhut on the 4th September. There they were met by members of the Japanese high command and enthusiastic crowds of Vietnamese. On the following day, the surviving American prisoners of war were flown out of Saigon on seven DC-3’s. Until the 12th September the OSS team was the only Allied presence in Saigon. On that day, the first British soldiers (an Indian Ghurkha division from Rangoon) flew in at about the same time as a company of French Paratroopers from Calcutta.

In the interim, the Americans under Dewey’s command, made contact with the “Committee of the South.” Set up by the Viet Minh, the Committee advocated “peaceful tactics” in the belief that they could prevent the return of the French through negotiations and with Allied help – Russian, Chinese and American. Opposing the Committee were the pro-Japanese Phuc Quoc Party as well as the United National Front comprised of Trotskyites, Cao Dai, Hoa Hao and other nationalist groups. They maintained that independence could not be supported by negotiations alone and fuelled that contention with rumours that the British planned to bring back French colonial rule. Stirring the pot was the Binh Xuyen (Saigon gangsters), who were taking advantage of the confusion to wreak havoc.

It is anyone’s guess why Dewey and his team remained in Saigon beyond the 12th September, by which time their primary goal had been accomplished. That they were OSS, and as such undoubtedly had secondary intelligence type missions, is a distinct possibility. More likely, with the war effort rapidly winding down, no one quite knew what to do with them, as the bureaucracy hadn’t caught up to them yet. However, the events on Sunday the 23rd September did catch up to Major Dewey and were to indirectly cost him his life. On that morning, before first light, the French forces under the command of Colonel Jean Cedile took over the control of all the main buildings of Saigon. When the curfew was lifted at 5.30am, the French citizenry bean a day long orgiastic fit of violence in the name of revenge for “Black Sunday.”

As the senior American in Saigon, Dewey attempted to register his complaint with Gracey whose job it was as commander of the British forces in Saigon to disarm the Japanese. It was Gracey’s order that released and armed the interned French troops, and it was Gracey who failed to act to prevent the bloodshed. On the next day, the 24th of September, suspecting Dewey of having connived with the Viet Minh and having interfered with British control Gracey declared Dewey persona non grata and ordered him out of the country. Major Dewey had two days to life.

At 9.30am on the morning of the 26th of September 1945, Major Dewey was scheduled to fly out of Tan Son Nhut airport to Kandy, Ceylon. With him on his trip to the airport was his deputy, Captain (later Major) Herbert J. Bluechel. Upon arriving at the terminal it was learned that Dewey’s flight was delayed and would not leave until noon. Returning to the Hotel Continental in the centre of Saigon, where he had been staying, Dewey was to discover that one of the members of his team (Captain Joseph R. Coolidge) had been shot and wounded at a Viet Minh roadblock ten miles outside of Saigon on the previous night. Dewey and Bluechel then drove to the British 75th Field Ambulance Hospital and briefly saw Coolidge who was suffering from a serve neck wound. In what was to prove ironic, Coolidge had been shot by the Vietnamese after speaking French and apparently being mistaken for a Frenchman.

After arriving back at the airport at 12.15 pm, the two OSS officers found Dewey’s flight had been further delayed. It was decided that they would eat lunch at the OSS headquarters located in the Villa Ferier just North East of the airport. With Dewey driving, they went past the golf course at the end of the runway and left the airport by the rear entrance. In the process, they passed near the spot where the spot where the last American, of many, was to die nearly thirty years later. For the previous several days many of the roads in the Saigon area had been blocked by the Viet Minh in an attempt to stop the movement of Allied forces. One of these roadblocks consisting of brush and tree limbs was a short distance down the road from the Villa. Both officers were familiar with it, having driven around it several times in the previous few days, including once that very morning.

This time it was different. Major Dewey, having reduced speed to about five miles per hour, noticed several Vietnamese hiding in the ditch alongside of the road. Shaking his fist at them, he yelled something in French that Captain Bluechel was not able to understand. At this time he was shot in the head by a burst of automatic weapons fire and killed instantly. After Dewey was shot, the jeep rolled in to the ditch and overturned. Captain Bluechel was not hit in the initial burst of fire and was protected by the jeep chassis from subsequent firing. Crawling in the ditch and running behind a row of hedges while firing his .45 calibre pistol at the Vietnamese, Bluechel was able to reach the OSS headquarters a short distance away. U.S. soldiers that were there, along with server war correspondents, held off the attacking Vietnamese in a battle that lasted several hours.

Accounts vary, but at least three to eight Vietnamese were killed while the Americans suffered no further casualties. In trying to call for help, it was discovered that the telephone lines had been cut. Being unable to contact anyone locally, Bluechel radioed OSS Headquarters Detachment 404 in Kandy, Ceylon, which in turn radioed the British in Saigon. The rescue was accomplished by two platoons of the 31st Ghurkha Rifles around 3.00 pm. Evacuation of all personnel to the Continental Hotel in downtown Saigon was completed by 5.00 pm.

There can be no doubt that the Vietnamese knew that the Villa Ferier was an American compound. However, Dewey’s jeep was not marked as to nationality; therefore, upon hearing him speak French it is probable to assume that he was mistaken for a Frenchman. His body was never recovered, making him the first American MIA in Vietnam, even though Ho Chi Minh ordered the Viet Minh to find it so that it could be returned. A reward of 5,000 piasters (an astronomical sum at that time) was offered by them for the Major’s body. For a short period, charges of plots and counter plots were raised by the war correspondents in the press around the world.

The Japanese had been providing support to the Vietnamese dissident groups since the early 1900s and had provided arms to the Cao Dai Church’s private army in the Saigon area during the war. Realizing this the British blamed the Japanese and placed Field Marshal Count Terauchi Hisaichi, the Japanese commander in Saigon, under house arrest. The French suspected the Americans of being anti-colonialist and the Vietnamese accused the French of creating the incident. The French, of course, said that the Viet Minh were guilty of cold-blooded murder, while some Americans, to complete the circle, pointed the finger at the British SOE claiming that they were attempting to remove their OSS competitors from Vietnam.

The point to realize here is that in 1945, in the southern portion of Indochina, much more so than in the north, there were many diverse political and religious groups. The Viet Minh didn’t control the south, in fact no one group did. In truth, the French were probably in the best position to bring everything back together again and prevent massive bloodshed. While there might be some validity to the revisionist argument that the U.S. should not have backed the French in Vietnam, that turning point had not been reached in 1945.

The final chapter of this saga was told in 1981 by a Vietnamese refugee who had escaped from Vietnam to France. In a statement made to the U.S. Embassy in Paris, it was learned that Dewey was ambushed by a group of Advance Guard Youth (military arm of the Viet Minh to Committee of the South). Led by a Vietnamese named Muoi Cuong, the group burned Dewey’s jeep and dumped his body in to a nearby well. Later, fearing discovery when they learned Dewey was an American, they recovered his body from the well and buried it in a nearby village of An Phu Dong. Both Cuong and his deputy Bay Tay, a deserter from the French colonial troops, were later killed fighting with the Viet Minh against the French.

This article was originally published in Behind The Lines magazine and authored by Gary Linderer

September 26, 1945: A. Peter Dewey becomes first American casualty in Vietnam.

Air Force Tech Sergeant Richard B. Fitzgibbon, Jr., murdered in Vietnam by a fellow airman on June 8, 1956, has been formally recognized by the Pentagon as the first American officially to die in that war.

With this decision, the Defense Department set November 1, 1955, as the earliest qualifying date for inclusion on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. It says this is the date the MAAG was officially established. Eight other pre-1961 casualties are already listed on the memorial.

The first death of an American serviceman in Vietnam occurred September 26, 1945. OSS (Office of Special Operations) Major (Lieutenant Colonel) A. Peter Dewey was killed in action by the Communist Vietminh near Saigon.

Some 128 members of a MAAG began supervising the use of U.S. equipment in Vietnam on Sept. 17, 1950. And two U.S. fliers contracted by the CIA were killed in action flying missions over Dien Bien Phu in 1954. The first U.S. advisors sent to actually train Vietnamese troops arrived February 12, 1955. Captain Harry Cramer, Jr., was killed in a munitions-handling accident October 21, 1957: His name had been the first listed.

There is another unique aspect to this story: Marine Lance Corporal Richard B. Fitzgibbon III — his son — was killed in action in Vietnam on Septtember 7, 1965. The Fitzgibbons are the only father-son honorees on the Wall.

When Fitzgibbon’s name is added to the Wall before Memorial Day 1999, the total number of names memorialized will be 58,214.

September 1945: First American Dies in Vietnam – Lieutenant Colonel A. Peter Dewey, head of American OSS mission, was killed by Vietminh troops while driving a jeep to the airport. Reports later indicated that his death was due to a case of mistaken identity — he had been mistaken for a Frenchman.

September, 1945 – Seven OSS officers, led by Lieutenant Colonel A. Peter Dewey, land in Saigon to liberate Allied war prisoners, search for missing Americans, and gather intelligence.

September 26, 1945 OSS Lieutenant Dewey killed in Saigon, the first American to be killed in Vietnam. French and Vietminh spokesmen blame each other for his death.

WWII Veteran was First American MIA in War Against Ho Chi Minh’s Forces

Lieutenant Colonel Peter Dewey of the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS), became the first American MIA in Vietnam on September 26, 1945, when he was ambushed by Ho Chi Minh’s forces (Vietminh). During World War II, the OSS, predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), trained and armed Vietminh guerrillas in the jungles of northern Vietnam to fight the Japanese.

Ho had just organized a “broad” communist front of “patriots of all ages and all types, peasants, workers, merchants and soldiers,” to drive both the Japanese and French out of Vietnam. His new organization, led by communists, appealed to many Vietnamese with nationalist sentiments. After the Japanese surrendered, Ho used the Vietminh as a power base for a Vietnamese nationalist movement to prevent the French from reestablishing colonial rule.

Dewey, the son of a conservative Republican Congressman from Chicago, (Charles S. Dewey) was the head of a detachment of seven OSS agents assigned to Saigon to search for and liberate Allied prisoners of war still being held by the Japanese.

He alienated the French and British hierarchy by making contact with the Vietminh. Major General Douglas D. Gracey, commander of a British force in Vietnam assigned there to disarm the Japanese, suspected Dewey of “conniving” with the Vietminh and ordered him out of the country.

Before leaving, Dewey summed up the situation in Vietnam: “Cochinchina is burning, the French and British are finished here, and we [the United States] ought to clear out of Southeast Asia.” Dewey and a colleague, Captain Herbert J. Bluechel, headed for the Saigon airport in a jeep with Dewey driving.

Dewey took a shortcut past the Saigon golf course, where he encountered a barrier of logs and brush blocking the road. After braking to swerve around it, he noticed three Vietnamese in the roadside ditch. He shouted angrily at them in French. Presumably mistaking him for a French officer, the Viet Minh replied with a burst of bullets that, according to Bluechel, blew off the back of Dewey’s head. Bluechel, unarmed, ran from the scene with a bullet knocking off his cap as he fled. Dewey’s body was never recovered. French and Viet Minh spokesmen blamed each other for his death.

In the fall of 1997, at an off-season hotel on Long Island, Vietnamese and American veterans gathered to recall when they had first met – fifty years ago in Hanoi or Saigon or the jungle headquarters of the Viet Minh along the Chinese border.

Both they and US-Vietnamese relations had been young and hopeful. Among those who attended the conference was George Wickes, now a professor of English literature at the University of Oregon, then a 22 year old serving in the Office of Strategic Services [OSS], who seized the opportunity to see more of Asia than he already had and joined a small OSS mission to Saigon in September 1945. His account of that trip and a subsequent one to Hanoi in the spring of 1946 recalls, with a kind of straightforward eloquence, a moment when Vietnamese independence seemed possible, even imminent.

There are many points in Vietnam’s thirty year war for independence when the historian wishes to freeze the frame. How easy it would have been for an accommodation to have been reached – in 1945 or 1954 or 1960 or 1963, millions of deaths before 1975. The force of George Wickes’ memoir of the time he spent in Saigon and Hanoi in 1945 and 1946 lies here, in one’s sense of the possibility that the United States government, like its O.S.S. field operatives, could have chosen for Ho Chi Minh rather than against him. There is an abundance of irony in this short, straightforward account: the death of Peter Dewey at the hands of those whose cause he supported, the use of Japanese troops under British command to burn the villages of Vietnamese the Allies were supposed to have liberated, the arrival of Wehrmacht veterans fresh from the battlefields of Europe to support the French colonial cause. The excerpts from letters Wickes wrote his parents at the time are as eloquent as they are prescient and his brief portrait of Ho Chi Minh, with which the account concludes, is especially powerful.

At the end of World War II I was in Rangoon serving as a soldier in the U. S. Army assigned to the military intelligence organization called the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Shortly after the Japanese surrender the OSS sent small teams of officers and men to the principal cities of Southeast Asia. Their mission was partly military (e.g., repatriating American prisoners of war, locating the graves of Americans killed during the war, and investigating war crimes), but in the absence of other representatives of the American government (e.g., the State Department), they also performed some peacetime functions, notably monitoring the political situation. When I heard that an OSS team was going to Saigon, I went to see the officer in command, Colonel Peter Dewey, and told him I wanted very much to go with him. He was unimpressed when I told him I had studied Vietnamese under the Army Specialized Training Program but asked if I knew French. When I replied that I had learned French at my Belgian mother’s knee, he gave me a one-word oral exam: “What is the French word for ‘street’?” He was not testing my vocabulary but my pronunciation, for “rue” is one French word few Americans can pronounce properly. Colonel Dewey, who spoke flawless French himself, was satisfied with my pronunciation and said, “All right, you can go. Be ready at 2:30 tomorrow morning.” So on September 4, 1945, we took off for Saigon. But first Dewey pinned second lieutenant’s bars on me. Of the eight OSS men going on the mission I was the only enlisted man and as such would be unable to deal with British and French officers. Similarly, Dewey upgraded the rank of some of the officers on the mission so that they could deal with British and French colonels and generals. All this was of course unofficial, but the OSS was a very informal organization that readily disregarded inconvenient Army rules and regulations. In Saigon we were to live like civilians, and the military life seemed far away. Our arrival in Saigon was quite dramatic. We were the first Allied soldiers to land there, and despite the surrender in Japan, we were not at all sure of the reception that awaited us. Southern Indochina was occupied by some 72,000 Japanese troops. Would they accept the surrender? We need not have worried. When we landed at Tan Son Nhut, some fifty of the highest-ranking Japanese officers were lined up on the tarmac waiting to receive us most respectfully. In the coming weeks the Japanese were to do exactly what they were told to do, which often meant serving as police and even at times as soldiers against the Vietnamese, sometimes even under the command of British officers.

Major General Gracey, the British commanding officer who arrived some time after we did, saw it as his mission not only to return southern Vietnam to the French when they were able to take over but meanwhile to put down Vietnamese resistance. Under the terms of the Allied peace accords, Vietnam was divided at the 16th parallel, with the British temporarily in command in the South and the Chinese in the North until such time as French forces could replace them. General Gracey, who was an old-fashioned product of the British Empire, brought with him colonial troops from India: Gurkhas and Sikhs and Punjabis, the kind of troops that had fought the Japanese and could be commanded to fight the Vietnamese. In all fairness, I must say that some of General Gracey’s staff officers, even high-ranking professional soldiers, did not share his views at all.

During our first few days we stayed at the Continental Hotel in the center of Saigon, where we were enthusiastically welcomed by the French residents and introduced to the French colonial way of life. But we soon moved out to a villa on the outskirts of town that had been occupied by a Japanese admiral, and there I spent most of my time during the next two and a half weeks, working with our communications officer, Lieutenant Frost, and our young Thai radio operator who went by the name of Paul. I had been trained as a cryptographer by the OSS, and my primary job was encoding and decoding messages to and from our headquarters in Southeast Asia. Our messages, which were then forwarded to Washington, reported on the activities of our team and on political developments in southern Vietnam. These reports would now make interesting reading and should by rights be available under the U.S. Freedom of Information Act, but to date all attempts to obtain copies have been frustrated. I know they still exist, for I once met an American Foreign Service officer who had read them and who was able to discuss the situation in Saigon in 1945 knowledgeably and with great interest. That was in 1963, yet in 1997, over half a century after we sent our reports, they are still inaccessible.

I do have some documentation of my own in the form of letters home, which my parents carefully preserved. But no letters survive for the period between September 8 and September 25, when I would normally have written two or three times, so I can only conclude that the military censor destroyed those letters because he felt they contained information that should be kept secret. Even though the war was over, the censor was still at work, as I know from passages that were sliced out of other letters. As a rule I was quite “security conscious,” as OSS personnel had been trained to be, but in my letters during the period in question I may have reported something of my clandestine” activities. For it was during this period that I met several times with representatives of the Vietnamese independence movement. Although I spent most of my time at the villa away from the center of things, I was kept well informed of developments by the members of our team who kept an eye on the doings of the French, the British, the Vietnamese, the Japanese, the Chinese. They were all caught up in the intense atmosphere of intrigue that prevailed in Saigon and all talked about it when they returned to the villa.

Colonel Dewey talked to me most of all, and I was impressed by his account of what was going on. He had spent the first year of the war in France, reporting on the political situation and serving as an ambulance driver with the Polish army; then as an OSS officer he had been with the French in North Africa and had parachuted into occupied France, where he had engaged in legendary exploits. But what impressed me most was his interpretation of the complicated political maneuverings of the different individuals and factions represented in Saigon, which he frequently explained to me. He was obviously contemplating a diplomatic career, and he encouraged me to do so too. I was 22 at the time and beginning to think about what I would do after leaving the army. Dewey had established contacts with the Viet Minh and perhaps other Vietnamese organizations. Because he was well known to the French and the British, both of whom objected to his contacts with “the enemy,” he could not very well meet with any Vietnamese without being observed. So he sent me several times to meet with them in the evening. The streets were dark, there were still many former prisoners of war floating about, and I would dress as they did in order to escape notice. I would go to a house on a quiet street and there meet for perhaps two hours with three or four men who were obviously deeply committed to the liberation of their country.

I have a very clear memory of those meetings but unfortunately no recollection of the names of the Vietnamese I met and only a general recollection of our conversations, which were conducted in French. I know that they were leaders in the independence movement and wanted us to let Washington know that the people of Vietnam were determined to gain their independence from France. During the war they had listened to Voice of America broadcasts which spoke of democracy and liberty, and they regarded the United States not only as a model but as the champion of self-government that would support their cause.

Three months later I learned that the French had put a price on my head, though in reality they had attached my name to Dewey’s head. The description was of a balding man with a mustache who was six inches shorter than me. Obviously this was Peter Dewey, and the only reason my name was involved was that someone must have learned of my meetings with members of the Vietnamese independence movement. I don’t believe I was ever in any danger, but clearly Dewey was persona non grata on account of his sympathy with the Vietnamese cause. As a matter of fact, all members of our mission shared his views, and our messages to Washington predicted accurately what would eventually happen if France tried to deny independence to Vietnam. This is only one of he many ironies of Saigon 1945.

Another was the death of Peter Dewey. On the morning of September 26 he went to the airport, where he was to be met by an American Transport Command plane from Bangkok and flown on his way home to be discharged from the army. But the pilot got drunk the night before and failed to appear on schedule. At midday Dewey decided to return to the villa by a cross-country route that he had taken before. There had been skirmishing in the countryside around Saigon, which was controlled by Vietnamese guerrillas, with roadblocks t strategic points. Such a roadblock was just down the road that passed in front of our villa, and as Dewey was going through that roadblock he shouted something in French at the Vietnamese who were posted there. Major Bluechel, who was with him, did not understand French but knew that Dewey was upset because one of our officers had been severely wounded in an ambush on his way back from Dalat the night before and supposed he shouted something about that. Dewey had wanted to fly the American flag on the jeep, but General Gracey had forbidden it, saying that only he as commanding officer had the right to fly his flag. Thus there was no way for the Vietnamese to know that this was an American jeep or that these were American officers. No doubt they took Dewey to be a Frenchman, and when he shouted at them, they opened fire with their machine gun, killing im instantly. The jeep overturned, but Bluechel was able to get away, running to our villa. The Vietnamese pursued him and attacked the villa, but though only three of us were able to shoot back, we succeeded in driving them away.

At the same time Frost radioed an SOS, and the British sent a troop of Gurkhas to the rescue. They proceeded as far as the roadblock, which had been abandoned by then, but did not find Colonel Dewey’s body or the jeep. In fact, the body was never found, though it was my grisly task for some time afterward to peer into newly dug graves where it was alleged to be buried. I will not claim that Colonel Dewey could have influenced American policy on Vietnam, though of all the Americans in Saigon in 1945, he was the one with the best political connections in Washington both through OSS and through his father, who was a member of Congress. But it was a tragic mistake that he should have been killed by people he was trying to help and a terrible irony that he should have died in what he called “a pop-gun war” on the day he he was supposed to go home after surviving all sorts of dangers during World War II.

So we moved back to the Continental Hotel, which was to remain our headquarters for the duration of our stay in Saigon. In fact, we now owned the hotel and paid no bills. The real owner, M. Franchini, loved Americans because they were good for business. He sold the hotel to Major Frank White for $2, thus placing it under American protection, and was then able to demand exorbitant prices of the many terrified French residents who wanted to sleep under the same roof. For a time Saigon was a city under siege. Lieutenant Frost and I, located with our radio in the annex of the Continental Hotel, had a good view from our balcony over the roofs of the city. Mostly we heard rather than saw the action. Things were generally calm during the day, but after nightfall we began to hear the sound of gunfire, beginning with the occasional stray shot by a jittery French soldier.

The French Foreign Legion, which had been interned by the Japanese the previous March, had now been released, with the result that its troops were trigger-happy and spoiling for a fight. With their release the shooting started in earnest. They defended the city, together with their new allies, the 6,000 Japanese troops stationed in Saigon. Every night we could hear Vietnamese drums signalling across the river, and almost on the stroke of 12, there would be an outburst of gunfire and new fires breaking out among the stocks of tea, rubber, and tobacco in the dockyards. One night the sound of machine gun fire and mortars and grenades went on for three hours. The following morning we were told that the Japanese had repulsed a Vietnamese attack across one of the bridges into the city. Though all this shooting made us somewhat nervous, we all grew daily more sympathetic with the Vietnamese. We no longer had any contact with representatives of the independence movement, but the French colonials we met made us increasingly pro-Vietnamese with their constant talk of how they had done so much for this country and how ungrateful the people were and how they would treat them once they regained control. They never made the slightest suggestion that there was any self-interest in “la mission civilisatrice de la France.” We knew a few French people we could respect but had no use for most of them, and our feelings were shared by Colonel Cedile, the new governor of Cochinchina who had been sent out from France by General de Gaulle; he would have liked to ship every colonial back to France and bring in an entirely new set of officials. Our views were also shared by the Free French soldiers who now began to arrive. Ironically, some of them thought they had come to liberate Vietnam.

Also ironically, the Foreign Legion brought some new recruits who spoke only German: seasoned veterans who had fought the war in Hitler’s army. Of course the Legion has always accepted volunteers with no questions asked. At the beginning of October General Gracey finally agreed to meet with the leaders of the Viet Minh who had been asking to see him ever since his arrival. Thereupon an armistice was declared, and things quieted down for a while, but only long enough for the British and French to bring in reinforcements: more Indian troops and French troops from France. Then the armistice was unofficially suspended, units of the British Indian Division ent on the attack, cannon fire could be heard throughout the day, and the sky became dirty with smoke from fires set by British troops. French warships appeared in the river and on the coast, and on October 6 General Leclerc, the so-called liberator of Paris, arrived to take command. Suddenly there were French flags flying everywhere and portraits of de Gaulle in every shop window. (A month earlier, when we arrived, the Vietnamese flag was flown alongside those of the Allied nations, and the portrait on display was that of Marshal Petain, the leader of the Vichy government.)

But the greatest event for the French of Saigon was the reopening of their country club, le Cercle Sportif. Wars and regimes and occupations could come and go, but life was not worth living without le Cercle Sportif. We went to the grand opening at the suggestion of Major White, who with his journalist’s sense of irony noted that British officers were now being feted by the same French residents who had collaborated and fraternized with the Japanese during the occupation. At his suggestion we went again a few days later and observed the social life of Saigon while the sound of cannon fire boomed regularly in the background and ashes from burning Vietnamese villages drifted down on the tennis courts. Ever since our arrival in Saigon former prisoners of war had been part of the street life–British, Australian, and Dutch, waiting to be repatriated. Just as the last Dutch P.O.W.s were leaving to go off and fight for a lost cause in Indonesia, a new kind of P.O.W. began appearing: hundreds of manacled Vietnamese being led through the streets in small groups by the French police. At the same time Vietnamese guerrillas launched their biggest midnight attack on the city, as if to serve notice that they had no intention of giving up the struggle.

But by the end of October the fighting had quieted down around Saigon, with only occasional skirmishing and sniping. Instead of doing battle with regular troops, guerrillas cut roads and bridges, burned buildings and stockpiles. Already it was becoming apparent that thousands of soldiers might have a hard time overcoming the resistance of a population of millions. In the middle of November I made a trip into the country north of Saigon–to investigate the latest report that Dewey’s grave was to be found in the cemetery of Thu Dau Mot. The effort was futile, as I knew it would be, and it seemed pointless to go to such lengths to recover a body, but the trip gave me the opportunity to learn how the British conducted their campaigns when I stayed with a regiment of Gurkhas. I liked the Gurkha soldiers and their British officers, and I like to think that they were going through the motions without taking things too seriously. After all, it was not their war, and firing cannonades into the peaceful countryside seemed about as futile and pointless as searching for Dewey’s body. It was on this occasion that I learned that some of the officers had led companies and battalions of Japanese soldiers in their “sweeps” of the country much as they led their Gurkhas now.

In a letter I wrote to my parents a few days later I gave my opinion of the political and military outlook:

“I do have some very reassuring information from Hanoi (Viet Minh Headquarters). It seems they are well-organized and realistic with a cosmic view of things. But France is determined to keep Indochina, determined enough to send out 120,000 troops. My visit to Thu Dau Mot also provided some information: that the Annamites have some military organization and that without the Japanese the task of clearing areas would be well-nigh impossible without large numbers. Also that the British have no great opinion of the French as soldiers. “A small percentage of Annamites are determined to sacrifice all and have a specific plan of action, but most of them, passively at least, want independence. The French are not quite so confident as they were at the start that this would be cleared up in a few weeks. And I believe that, unless they always keep large arrisons and patrols everywhere, they will not be able to keep the country submissive as it was before. The Annamite’s great advantage lies in the fact that he is everywhere, that he does not need to fight pitched battles or organize troops to be a threat and that no amount of reprisal can completely defeat him. I cannot say how it will end, but at least it will be a long time before Frenchmen can roam about the country with peace of mind.”

I do not recall how I acquired that “very reassuring information” from Viet Minh headquarters in Hanoi. I do not believe I could have been in touch with the Viet Minh in late November, but I could have heard from one of my friends in OSS who had been a fellow student in the Vietnamese language program. Four of them were in Hanoi, and another had just arrived in Saigon. Or I could have heard from someone like my friend Captain annerjee, a very political and very astute Communist in the British Army, or Roger Pinto, a French professor who had made a study of Vietnamese politics during the war when he was interned for being a Jew.

My departure from Saigon on or about December 6 was as sudden as my arrival. Without any warning I was told to leave on twenty-four hours’ notice. It seems that U.S. Army Headquarters in India had just discovered that I was impersonating an officer and had ordered OSS to have me cashiered. To save its own face, OSS simply transferred me to its headquarters in Singapore. There I was allowed to choose my next assignment and asked to be sent to Bangkok. OSS sent me by sea as an escort for an American car that was being shipped to the U.S. Legation in Bangkok. Of course this was only a pretext to give me a pleasant leave in the form of a cruise on the South China Sea. What OSS did not plan is that the freighter would first stop off in Saigon to deliver cargo, arriving there on December 25. So I was able to spend a four-day Christmas vacation with my former colleagues in Saigon before the ship sailed again. Three of the original officers who had arrived in early September were still there. One of them, Major Frank White, had been our chief liaison with the British all along and had maintained good relations with British intelligence as well as other sources. He had been a journalist before the war and was to be a very successful journalist again after the war; meanwhile he was the most knowledgeable and enterprising officer on the mission. He had always been quite friendly with me, and now he made a proposal that appealed to me at once: that we try to obtain authorization to go to Hanoi to interview Ho Chi Minh.

June 2003:

Dear Mr Patterson,

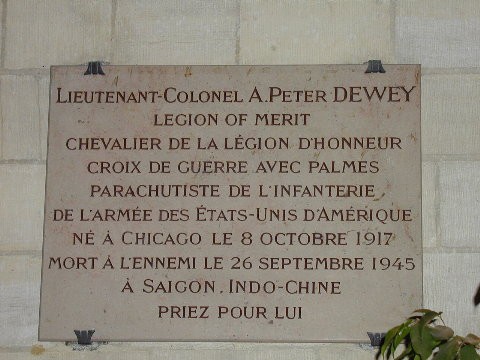

I was in Bayeux, Normandy last week and during a visit to the Cathedral came across this memorial plaque in a side chapel. (Picture attached).

I looked the name up on Google.com and came across your website and I thought I’d let you have it in case it was of interest to you, as it was to me since I wrote my university dissertation on the French Indo-China War 1945 – 1954.

I thought the simple “Pray for him” at the end was quite touching.

Kind regards

Patrick Milne

Harrogate

England

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard