Local Man To Bury His MIA Vietnam Vet Father

More Than 1,800 Americans Are MIA From Vietnam War

SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA – Among the six MIA Vietnam War servicemen whose remains were recently recovered is the father of a University of California, San Diego Professor, who will attend his funeral this week.

What happened to Air Force Colonel Harding Smith of San Jose, California, has taken 38 years to find out. The navigator was just one of the more than 1,800 Americans who the Department of Defense considers to be missing in action from the Vietnam War.

Now, however, Smith and five other servicemen have been found and identified.

“Whenever the subject comes up, there’s always a knot in my stomach,” Smith’s son, Gene, said. “And, uh, it’s, it’s always difficult.”

In 1966, Harding Smith and his crew were aboard an AC-47 gunship, flying a nighttime mission over southern Laos. Their aircraft was believed to have been hit by anti-aircraft fire, and witnesses reported seeing it crash, but an aerial search of the site did not yield any evidence of survivors.

“It was fairly heavy jungle area,” Gene said. “A call to bail out was heard, but no parachutes were seen and, given what was going on in there, one wasn’t certain if you wanted to know if they survived or not.”

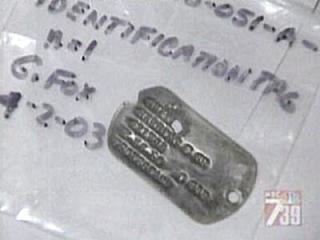

In 1994, searchers found Smith’s military identification tag and the card he carried that listed the rules of the Geneva Convention, as well as the aircraft wreckage at the suspected crash site.

Less than a year later, some of the human remains of the crew were recovered.

“It was pretty weird,” said Gene. “Same knot in the stomach, dredging up of a lot of old feelings…. I didn’t hold out any hope. I think my mother always did, and that was very difficult for her.”

Gene is the sole family survivor. He will be at Arlington National Cemetery on Friday when his father and fellow crewmen will be buried with full military honors.

It was the kind of encounter that is supposed to happen to someone else, anyone else.

Back in 1966, Gene Smith was a freshman at the California Institute of Technology, and the military had dispatched a young man to campus who “had the unfortunate duty of coming over to me with a telegram saying, ‘We regret to inform you that your father is missing in action.’

“He gave me some of the details,” Smith said the other day, the memory of it all still quite clear, the whole thing welling up inside him again. “Flying a night mission. Anti-aircraft fire in the area. The plane was on fire. A call to bail out was heard, but no parachutes were seen.

“I didn’t know what to do. I went out and walked around for a long time,” Smith said. Then the government flew him up to the Bay Area, and he joined his mother, who had just received a similar telegram at the family home near San Jose.

The details of what happened were the chance of war: On a Friday night —

June 3, 1966 — an American AC-47 gunship flying reconnaissance over southern Laos was shot down by ground anti-aircraft fire.

Over the next nine years, the status of Smith’s father, Air Force Lt. Col. Harding E. Smith, 48, went from MIA — with its mixed connotations of yes, he’s alive, or maybe he’s not — to KIA, with its incontrovertible finality. Around 1975, the family had a memorial service.

In 1995, a joint U.S. and Laotian search team excavated the site where the plane crashed. It found bits and pieces of the plane’s crew, including Smith’s dog tag and his Geneva Convention card. Recently, through forensic science, the government was able to say the entire crew of six was accounted for.

Friday morning, in a half-hour ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery, Gene Smith buried his father. Standing with his cousin, Meg Bailey — who, as Smith’s surrogate sister, had gone through the same kind of pain for 38 years — Smith watched as the casket was removed from a hearse, placed on a horse-drawn caisson and taken to the burial site, presided over by two chaplains. There was a 21-gun salute and an Air Force band.

“I thought for the most part the ceremony was appropriate,” Smith said in a telephone interview from Virginia.

It was the end of a period in Gene Smith’s life that began when he was growing up as an Air Force brat, the only child of a man who would serve in three major conflicts.

Harding Smith was a B-29 navigator in the last part of World War II. When Korea flared up five years later, Smith went back to war, and when that conflict ended he stayed in the Air Force.

By the summer of 1965, the family was living in Tucson, near Davis- Monthan Air Force Base, where Smith was planning flight missions. Then, suddenly, “he got orders for Vietnam,” his son said, and he was gone.

There wasn’t much communication between the colonel in Vietnam and his son in Arizona. It was long before e-mail and satellite-phone hookups, and there was something else.

As he was being interviewed the other day, Gene Smith, now 57, was asked how he felt about dredging all this back up. “It’s not terribly painful, but” — here he hesitated for a moment — “I had been a teenager then, and my father and I were not on the best of terms when he went to Vietnam. There had been some conflict, as is frequently the case, normal teenage stuff. We saw things a little differently. I was probably more liberal, politically.”

He paused for another second. “So there are a lot of unresolved issues, unresolved feelings. I’m older than my father was when he was shot down. I had hoped at one point that being declared killed in action, or at the memorial service, there would be some closure there, but I’ve just never found it. So . . . it is painful.”

And the sudden loss was equally painful for Gene Smith’s mother, Bernice. This was the love of her life.

In the days and years after she learned her husband was missing in action, “it was just sort of a long period of agony,” Smith said. Bernice Smith moved from Tucson to Santa Clara to be closer to family — her sister lived in Gilroy — and she and her son became active in the National League of Families of American Prisoners and Missing in Southeast Asia.

“There was absolutely no information about my father until the end of the war (in 1975),” Smith said. “I don’t think she ever really gave up hope, but it was a tremendous shock to her, one that I don’t think she ever recovered from.”

For the next 20 years, Bernice Smith was a librarian in Gilroy and, as the years passed, “she accepted that he must be dead,” her son said. “There was never any consideration of searching for further romantic interest because of how much she loved him. She never remarried.” Bernice Smith died in 1995.

For her son, the 1960s and ’70s were a jumble of personal conflicts. His father had been a navigator aboard one of the most fearsome weapons used during the war in Southeast Asia: The AC-47 was known as “Puff the Magic Dragon,” after the Peter, Paul and Mary hit tune, and the dragon part connoted the aircraft’s abject lethality. The plane’s job was to circle tightly over one spot, spitting out 6,000 rounds a minute from its 7.62mm Gatling guns, pulverizing anything on the ground.

Navigating this beast was his father’s job, one that, in the abstract, was hated by most of the students at UC Berkeley, where, during the still- fractious ’70s, Smith was pursuing a graduate degree in astrophysics.

“There was this schizophrenic thing of being at school in Berkeley, with all the ferment, and having my father shot down and missing,” he said. “At that time, I’d realized that the Vietnam War was a pretty senseless exercise, and I shared the view of most of my colleagues at Berkeley; I was at the demonstrations over the invasion of Cambodia. But it was very difficult. I didn’t feel I could be too vocal because of my father, and it was a difficult subject to discuss with my mother.

“Under other circumstances — had he not been missing — she might have come to similar conclusions, which is that what he was doing had no purpose,” he said.

Smith went on to a successful life. He joined the UC San Diego faculty in 1977 and is now a professor of physics. He has a wife, daughter and stepdaughter, and he loves to ride horses.

After the remains of the AC-47 crew were recovered, they were taken to the U.S. Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii. The identification process can take years, and as it was going on the military kept Smith informed. About a year ago, the Air Force sent Smith his father’s dog tag.

Hours after Friday’s ceremony, Smith was quiet. Asked if he felt some sort of closure from when he last saw his father, he said, “I think that aspect of it will never happen. I guess I felt some closure, but there are some things that will never happen.”

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard