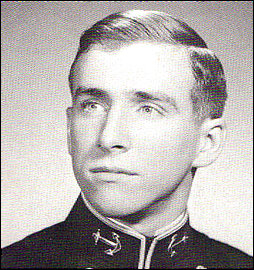

- Full Name: MELVIN SPENCE DRY

- Date of Birth: 3/13/1946

- Date of Casualty: 6/6/1972

- Date of Death: 6/6/1972

- Home of Record: KINGS POINT, NEW YORK

- Branch of Service: NAVY

- Rank: LT

- Casualty Country: NORTH VIETNAM

- Casualty Province: OFFSHORE, PR&MR UNK

Lieutenant Melvin Spence Dry, was a Navy SEAL who was killed in action in 1972 while leading a rescue effort in North Vietnam to free U.S. prisoners of war. He was the last Navy SEAL killed in Vietnam. The nature of his mission remained classified by the Navy until this year. He was posthumously awarded a Bronze Star in a ceremony at the U.S. Naval Academy in February.

Tuesday, February 26, 2008

Riding in the dark inside a Navy helicopter over rough waters off the coast of North Vietnam, Navy Lieutnant Spence Dry didn’t hesitate when the time came to jump.

Dry, commanding a SEAL team, was determined to link up with the submarine USS Grayback in the waters below to continue a daring mission to rescue U.S. prisoners of war trying to escape from the Hanoi Hilton, the infamous North Vietnamese prison.

” ‘I’ve got to get back to Grayback,’ ” John Wilson, the helicopter crew chief, recalled Dry saying. “He was adamant that the mission go forward.”

Finally, the helicopter crew spotted a flashing light they believed to be the submarine’s beacon. Wilson slapped Dry on the shoulder, the signal to jump, and Dry disappeared into the night, followed by the three SEALs in his team.

But the helicopter was flying too high and too fast, and Dry, 26, died instantly upon impact with the water, the last SEAL to die in Vietnam. The circumstances of his death would remain tightly classified for more than three decades. Dry was given no recognition by the Navy, and his family received few answers. The Navy labeled it a training accident.

The U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis declined to add the 1968 graduate to its listing of alumni killed in action displayed in Memorial Hall, citing the accident classification.

Yesterday, inside that ornate hall considered the heart of the academy, more than 200 friends and family members from the Washington area and abroad gathered for a ceremony in which Dry was posthumously awarded the Bronze Star medal with valor. His name was also formally added to the alumni scroll in Memorial Hall.

The guests included Wilson, the helicopter crew chief, as well as many of Dry’s SEAL platoon members and the former commander of the USS Grayback. The Naval Academy’s Class of 1968 showed up in force, including Admiral Michael Mullen, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Also paying his respects was retired Air Force Colonel John Dramesi, one of the prisoners Dry was attempting to rescue.

Standing in the back of the hall were several dozen midshipmen who hope to become SEALs after graduation.

“Today has been a long time coming,” said Rear Admiral Joseph D. Kernan, commander of the Naval Special Warfare Command, a speaker at the ceremony.

“It’s sad that it’s taken this long, but the upside is he’s finally been recognized,” said Wilson, who flew from Hawaii for the event.

Dry’s younger brother Robert told the audience that the ceremony “fulfills my parents’ fondest wish, that their firstborn son be recognized for his sacrifice. It’s a fitting end to the tragic events that occurred 35 years ago.”

Spence Dry: A SEAL’s Story

By Captain Michael G. Slattery, USN (Ret.), and Captain Gordon I. Peterson, USN (Ret.)

Early in 1972, two U.S. airmen being held as prisoners of war at the infamous “Hanoi Hilton” prison set in motion an escape plan. In response, the U.S. Pacific Fleet orchestrated what became known as “Operation Thunderhead,” a rescue mission that played out that June in the Red River delta.

Special operations forces from SEAL (sea, air, land) Team One and Underwater Demolition Team (UDT)-11 were assigned to assist the POWs. One of them, Lieutenant Melvin Spence Dry, U.S. Navy, was killed on the classified mission—the last SEAL lost during the Vietnam War. His father, retired Navy Captain Melvin H. Dry, a 1934 Naval Academy graduate and a submariner, spent the rest of his life trying to learn the circumstances surrounding his son’s death. The details, however, were long shrouded in secrecy.

Following his Naval Academy graduation in 1968, Spence Dry reported to postgraduate school. Sea duty followed on the destroyer USS Renshaw (DD-499) but he wanted to join the special-warfare community. Late in 1969 he reported to the 20-week Basic UDT/SEAL Training course of instruction at Naval Amphibious Base, Coronado, California.

Class 56 initially numbered 12 officers and more than 100 enlisted men, including an Academy classmate, Lieutenant (j.g.) Michael G. Slattery. At graduation in June 1970, the class numbered five officers and 22 enlisted. The officers—Mike Cadden, Spence Dry, Jerry Fletcher, Jim Hoover, and Mike Slattery—formed a particularly close bond. Four of the officers, including Dry, were assigned to UDT-13 and deployed within a few months to the Republic of the Philippines. Dry soon moved on to the Republic of Vietnam, where he served for three months as officer-in-charge of the team’s Detachment Hotel, based near Danang. There he led his detachment on river reconnaissance, combat demolition, and search-and-destroy operations along Vietnam’s Ky Lam River.

Upon their return from Vietnam in 1971, Slattery, Fletcher, and Dry were assigned to SEAL Team One. The team’s primary mission was to engage in unconventional warfare, conducting counterguerrilla and clandestine operations in coastal and riverine areas, but with President Richard Nixon’s “Vietnamization” policy in full swing, the only combat assignments were one-year tours as advisors to South Vietnamese units.

In November 1971, however, Dry was given the chance to form his own contingency platoon and prepare it for a six-month deployment to the Western Pacific. Lieutenant Robert J. Conger Jr., Dry’s assistant officer-in-charge at the time, recalled that he and Dry spent two weeks screening more than 80 enlisted volunteers to identify the 12 best qualified for SEAL Team One’s “Alpha” platoon.

“Spence was sure of his direction, and the positive, yet attainable, goals he set for himself gave the platoon a unity and esprit seldom found in any organization,” Conger said. One of the more experienced combat veterans in the platoon described Dry as one of the best officers that Team One ever had. Chief Petty Officer (soon to be Warrant Officer First Class) Philip L. “Moki” Martin, a highly experienced SEAL who had served multiple combat tours in Vietnam, rounded out the platoon’s leadership. He considered Dry an “operator”—just about the highest accolade a SEAL can give. The 11 other enlisted men also reflected a wealth of combat experience.

Alpha platoon deployed to Okinawa for additional training and stood by.

Operation Thunderhead

Armed with fresh intelligence that the prisoners were planning to steal a boat and travel down the Red River to the Gulf of Tonkin, Admiral Thomas H. Moorer, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, on 15 May 1972 authorized the U.S. Pacific Command to execute Operation Thunderhead, a rescue plan proposed by the Pacific Fleet a month earlier. Full details of the operation were known to only a handful of officers individually cleared by Admiral John S. McCain Jr., the PACOM commander.

Dry’s platoon left Subic Bay in April in the amphibious-transport submarine USS Grayback (LPSS-574), skippered by Commander John D. Chamberlain. The Grayback, formerly a Regulus guided-missile submarine, had been converted in 1968 to support clandestine operations. The diesel-electric submarine was modified to carry approximately 60 troops plus four SEAL delivery vehicles (SDVs) in two “wet” hangars on her bow. The SDVs were small, free-flooding, unpressurized fiberglass minisubmarines equipped with rudimentary navigational equipment.

The rescue plan was straightforward, but challenging. Dry and Martin would launch at night from the submerged submarine in an SDV piloted by two UDT-11 operators already embarked in Grayback and head for a small island off the mouth of the Red River. There the two SEALs would establish an observation post and watch for any sign of the escapees. “The time Spence and I were to spend on the island was a minimum of 24 hours and up to 48 hours,” Martin remembered. “We were to look for a red light on a boat during the night and a red flag during the day.”

Should the escaping POWs be sighted, the two would intercept them and coordinate their rescue with the waiting ships of the Seventh Fleet. North Vietnamese soldiers garrisoned the island. Occasional Vietnamese fishing boats plied the waters, and enemy patrol boats were always a possibility. There were other concerns, including a night underwater lock-out and launch from the Grayback in an under-powered SDV; a cold, submerged transit to the island in the confined and totally dark hold of the unproved free-flooding Mark VII vehicle; strong currents and tidal conditions; and the need for precise underwater navigation (in the days before the Global Positioning System).

Seventh Fleet helicopters conducted over-water night surveillance along North Vietnam’s coast as the date for the escape approached. The Grayback arrived on station on 3 June 1972. Chamberlain and Dry decided to conduct a clandestine SDV reconnaissance mission that night. After dark, Chamberlain launched the vehicle at the end of flood tide to provide a maximum amount of slack water; he planned to recover it on the ebb tide. “Operation of a four-knot SDV in a two-knot current was extremely challenging,” Chamberlain recalled, “and required not only excellent driving skills but also a fine understanding of navigation.”

Dry, Martin, and the two UDT operators, Lieutenant (j.g.) John Lutz and Fireman Thomas Edwards, launched from the submerged Grayback shortly after midnight, but a combination of navigational errors and the strong current took them off course. After searching for more than an hour without sighting the island, the crew was compelled to abort the mission and, unable to locate the Grayback, scuttle their underpowered SDV after its battery power was exhausted. They planned to head out to sea if they could not locate the submarine.

The men were treading water a few miles off the coast when rescued early the next morning by a combat search-and-rescue HH-3A helicopter assigned to Helicopter Combat Support Squadron (HC)-7. To preserve operational security, Lutz used the helicopter’s door gun to sink the SDV, which was too heavy to be retrieved. The four men were flown to the nuclear-powered guided-missile cruiser USS Long Beach (CGN-9), the command ship for Thunderhead, where they debriefed, communicated briefly with the Grayback, and planned their next steps.

“We’ve Got to Get Back to Grayback”

Dry, aware of the impending launch of the second SDV, knew that he and his men had to return to the Grayback quickly. The Navy was prepared to let the mission run up to three weeks, if necessary; given Dry’s key leadership role and Martin’s combat experience, both were needed if a follow-on SEAL insertion using another SDV was to succeed.

The decision was made to transport them by helicopter from the Long Beach for a night water drop (a “cast” in SEAL/UDT parlance) next to the Grayback at 11 p.m. on 5 June. The plan called for the helicopter’s crew to make visual contact with the Grayback’s infrared (IR) signaling light atop the submarine’s snorkel mast, which operated in beacon mode during Operation Thunderhead. In this configuration, it was a revolving, flashing red light. During briefings with the pilots, Dry and Martin emphasized that the maximum limits for the drop were “20/20″—20 feet of altitude at an airspeed of 20 knots, or an equivalent combination.

The weather was overcast, with sea state 1-2, indicating a maximum wave height of approximately four feet. HC-7’s “Big Mother” crew was faced with finding the Grayback while maintaining radio silence in cloudy weather on a dark night. Martin noted high winds and two- to three-foot swells as he boarded the helicopter on the Long Beach.

Problems began soon after the helicopter arrived near the Grayback’s expected position. Multiple passes failed to reveal the submarine. To complicate matters, Dry could not communicate directly with the helicopter’s pilot. Only the crew chief, Petty Officer First Class John L. Wilson, and Lieutenant Commander Edwin L. Towers, a Seventh Fleet staff officer temporarily assigned to the operation, were linked through the helicopter’s internal communications from the cabin to the pilots in the cockpit.

As the aircrew desperately searched for the Grayback’s beacon, Dry and his men prepared to enter the water and lock-in to the submerged submarine. Several approaches were aborted when it proved impossible to confirm the submarine’s presence. At one point the helicopter inadvertently passed over the surf line and flew over North Vietnam when the crew mistook lights from a dwelling for the submarine. “It was a very hair-raising night,” Wilson remembered.

During another difficult approach to the intermittent light just prior to the helicopter’s last pass, the pilot overshot, flared the helicopter to dissipate airspeed as he transitioned to a hover, and then backed down toward the light. He descended within ten feet of the surface in a tail-down attitude. Water splashed into the cabin and almost swamped the helicopter before the pilot, warned by his crew chief, waved off for another try.

In near-desperation Wilson passed his helmet (with its lip microphone) to Dry so he could talk directly to the pilot about his concerns with the helicopter’s altitude and speed. Dry and Martin had ample reason to worry.

According to a post-mission assessment, Dry informed the helicopter crew that they were too high, too fast, and downwind. Specifically, they were approaching the drop point with the winds, estimated at 15 to 20 knots, on the helicopter’s tail. The velocity of the tail wind, added to the helicopter’s forward speed, was well beyond the 20-knot ground speed needed for a safe jump. “They wanted us out, and we felt the altitude was too high and the speed too fast,” recalled Martin, an experienced parachute jumpmaster. “As drop-master, I was looking for the tell-tale signs of spray from the helo—either coming in the door or when I looked toward the rear and below the helo.”

Mindful of the helicopter’s fuel state, Dry told Martin that time was running out—they needed to return to the submarine. “I remember seeing Spence’s face in the dim red helo light,” Martin said. “His last words to me were, ‘We’ve got to get back to Grayback.'”

Finally, the helicopter crew observed a flashing light and assumed they had sighted the submarine’s beacon. The pilot, not trusting the helicopter’s automatic stabilization equipment, made a manual approach and, as he neared a hover, called, “Drop, drop, drop.” “It was dark and windy,” Martin said, “but I could see the helo’s sea spray, especially on the dark sea surface.”

Wilson, a veteran combat search-and-rescue diver with 29 career rescues to his credit when he retired as a chief petty officer, slapped Dry on the shoulder—the signal to jump. The final decision rested with Dry, but there was no hesitation. He dropped from the helicopter into the darkness, followed in quick succession by his three team members as the helicopter began to gain altitude and airspeed. “I knew right away that we were too high and too fast,” Wilson related, “but it was too late.”

“I was third in the drop,” Martin said. “I exited and counted—one thousand, two thousand, three thousand . . . followed by ‘God dammit,’ and then I hit the water. I believe by my count that I was over 50 feet, possibly even 60 feet.” Again, according to Martin, the cast was conducted downwind, adding another 15 to 20 knots of forward velocity when the jumpers hit the water.

The chief of naval operations told Captain Dry that his son had exited the helicopter at about 35 feet, but the survivors have no doubt that the helicopter was much higher. “A combination of too much speed and altitude [did] not allow any jumper to get a proper body position to enter the water. All four of us were injured,” Martin related.

Dry died immediately of “severe trauma to the neck” caused by impact with the water, according to the Navy’s death report. Two other team members were badly shaken, and one was seriously injured. Martin and Lutz answered one another’s call, but there was no reply from their other teammates. Martin set out to find them. Edwards had broken a rib and was semi-conscious when Martin found him and inflated his life vest. Visibility in the water was later estimated at 10 feet, but the SEALs said it was closer to zero in the muddy water off the enemy’s coast.

There was no response to their calls for Dry, although they estimated they were only 15 to 20 yards apart on their cast.

Worse, the flashing lights detected by the helicopter crew were not on the Grayback; in fact, they were the emergency flares and strobe lights used by the crew of the second SDV to alert the incoming helicopter to their own predicament.

Unknown to the pilots and the SEALs on Dry’s helicopter before their drop, the Grayback had launched its second vehicle several hours earlier for abbreviated requalification launch-and-recovery operations. According to Chamberlain, the vehicle was to remain within acoustic homing beacon range of the submarine so that it could return as desired. Upon launch, however, it foundered in approximately 60 feet of water. Eventually, its crew of four abandoned it when their air ran out; subsequently, they made an emergency free ascent to the surface.

Chamberlain, with radar contacts indicating North Vietnamese patrol boats, had radioed to abort the night drop, but his message arrived too late.

Martin, Lutz, and Edwards saw a strobe light, heard voices, and swam to the second SDV’s team. The group drifted with the seas. About 1 a.m., they found Dry’s lifeless body, inflated his life vest, and held him and Edwards in tow as they swam seaward to be rescued.

The North Vietnamese patrol boats in the area did not detect them, and an HC-7 helicopter alerted by Chamberlain rescued the men at dawn and returned them to the Long Beach. Dry’s body and the seriously injured Edwards were then flown to the carrier USS Kitty Hawk (CV-63).

The Grayback remained on station in the shallow waters for an additional two days—relying on periscope sightings to detect any escaping POWs—before Chamberlain was ordered to a safer patrol area. The remaining six members of the mission later were transferred from the Long Beach to the submarine on 12 June. With the likelihood of a successful prisoner escape by sea lessened by the recent U.S. mining of North Vietnam’s ports and rivers, Operation Thunderhead was soon terminated.

A Father’s Quest

Dry was the last SEAL killed during the Vietnam War. As it turned out, the leadership at the Hanoi Hilton had called off the escape attempt over concern for the plan’s risk and fear of retribution. Unfortunately, there was no way of quickly informing anyone outside the prison walls about this decision. Those assigned to detect and recover the fleeing Americans continued to dedicate themselves to their rescue.

In Scotland, Dry’s parents were notified on 12 June of their son’s death in a “training operation,” the government’s cover story for the secret mission. Captain Dry’s diary entry the following day consisted of one word: “Desolation.” His son’s remains were returned to the United States, and he was buried at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors on 22 June. Admiral Bernard Clarey, the U.S. Pacific Fleet commander, met with Captain Dry in the Pentagon and explained the mission in a general way.

The operation’s cover story did not ring true as news of the mission slowly filtered back to Coronado. Like the men of SEAL Team One, Captain Dry also was dissatisfied with the Navy’s explanation. Over the next 25 years he sought, in vain, to induce the Navy and the Naval Academy to recognize his son’s sacrifice.

The Navy did not share the findings of its 1972 joint investigation. “In nearly five years I’ve been given no information about exactly what happened at the scene of the accident,” he wrote five years later. Finally, the Grayback’s commanding officer, in a personal letter to Dry in 1981, provided a fuller accounting of his son’s death. Others in the Navy who served with his son also filled in additional details through the years.

With the exception of an “end-of-tour” Navy Commendation Medal awarded to Lieutenant Conger, it appears that no member of Dry’s team was decorated or otherwise recognized for their actions during the daring rescue mission—not even Warrant Officer First Class Martin, who saved the life of the seriously injured member of his team and rallied the remaining survivors until their rescue. Captain Dry’s attempts to have his son awarded a posthumous Purple Heart were denied by the Department of the Navy, which maintained his loss was not the result of enemy action.

Similar requests to the Naval Academy during the 1990s to recognize the younger Dry’s combat death also were unsuccessful, despite interest by former Secretary of the Navy James H. Webb Jr., one of Dry’s Academy classmates. “The naval service is rightly stringent in awarding the Purple Heart and in assigning the status of killed in action,” Webb wrote in the Naval Academy’s Alumni Association’s magazine in 1999. “But in the complicated world in which we have lived since the end of World War II, many who perished during operational missions, directly related to national defense, paid a price that was clearly measurable in the Cold War’s victory.”

The Naval Academy did not include Spence Dry’s name on a listing of its alumni killed in action displayed in Memorial Hall owing to the Navy’s initial determination of his death as an operational accident. “In order to be listed on that memorial,” the Academy’s Alumni Association said, “the Secretary of the Navy must have designated the individual KIA [killed in action] on the casualty report. Lt. Dry was not noted in this category.”

Dry’s leadership and dedication remain unrecognized by the Navy, although those most familiar with his loss have no doubts regarding his leadership and heroism that night. Ten days after the fateful night cast, all 13 surviving men of the platoon signed a joint letter to Captain Dry honoring their fallen commander. They wrote that “. . . His memory will remain with us so long as man values positive leadership and courage in the face of danger.”

Captain Dry died in 1997. By then, he knew most of the details surrounding his son’s death, but his quest to have the Navy honor his son’s wartime sacrifice went unfulfilled. Father and son are buried in a common grave in Arlington National Cemetery. Captain Dry’s dolphins are engraved on the top of the tombstone’s face; his son’s SEAL insignia is engraved at the bottom.

Epilogue

On 4 June 2004, the Naval Academy dedicated its renovated Memorial Hall, where the names of more than 2,500 graduates killed during operations “while forward deployed, training, or preparing to deploy” are now listed on 44 panels. The Class of 1968’s plaque, with Spence Dry’s name, is located just to the left of the display naming those alumni killed in action with the enemy. In December 2004, the Naval Academy Foundation confirmed that Spence Dry would be recognized as an operational loss during the Vietnam War. His name will be included on the Academy’s Vietnam Memorial when it is renovated in 2005.

Authors’ Notes

The authors interviewed mission participants and relied upon several published accounts of Operation Thunderhead in the preparation of this article, including George J. Veith’s Code-Name Bright Light, The Untold Story of U.S. POW Rescue Efforts During the Vietnam War (New York: The Free Press, 1998), pp. 328-329. Veith provides a meticulously researched, well-annotated, and comprehensive summary of POW escape attempts and rescue missions during the Vietnam War. The most complete first-hand account, Operation Thunderhead, was published in 1981 (La Jolla, Calif.: Lane & Associates). It was written by Lt. Cdr. Edwin L. Towers, a U.S. Seventh Fleet staff officer assigned to the mission and present with Dry the night he died. Orr Kelly’s Brave Men, Dark Waters: The Untold Story of the Navy SEALs (Novato, Calif.: Presidio Press, 1992) also describes the operation. Kevin Dockery devotes a chapter to the mission in Free Fire Zones: The True Story of U.S. Navy SEAL Combat in Vietnam (New York: Harpertorch, 2000).

We also interviewed Spence Dry’s brother, Robert W. Dry, in June 2004. He gave us access to his father’s records on Spence Dry’s Navy career and his death during Operation Thunderhead, which are preserved in two large binders containing copies of his personal correspondence, letters from mission participants, declassified Navy message traffic, and published accounts relating to the operation. They provided valuable original-source information for this account of his brother’s death.

Additional information came by e-mail to the authors from Richard C. Hetzell on 3 August 2004, and from a letter to Capt. M.H. Dry from Lt. Robert W. Conger Jr., of 16 June 1972, signed by all members of Lt. Dry’s platoon. In addition to Conger, the platoon consisted of Philip L. Martin, Samuel E. Birky, Timothy R. Reeves, Richard C. Hetzell, Eric A. Knudson, Robert M. Hooke, Frank Sayle, David Ray Hankins, John M. Davis, Michael J. Shortell, Barry S. Steele, and William B. Wheeler.

We reviewed a naval message from Admiral John S. McCain Jr., Commander-in-Chief, Pacific, to Admiral Bernard Clarey, Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet (date/time group 160112Z May 1972), in the Library of Congress (LOC) Public Document Section (PDS) LC 92/302 reel 61. Interestingly, Capt. M.H. Dry had served as McCain’s executive officer when the latter officer commanded the submarine USS Gunnel (SS-253) during World War II.

Several of the SEALs and UDT operators assigned to Operation Thunderhead felt that an overemphasis on operational security constrained their ability to plan and execute their special-warfare mission tactically. More experienced but lower-ranking SDV pilots, for example, were not fully briefed on the mission nor consulted during tactical mission planning. (Interview with Col. Samuel E. Birky, U.S. Army, Fort Bragg, N.C., 23 July 2004, and information in e-mails to the authors from Richard Hetzell, 3 August 2004, Thomas Edwards, 19 June 2005, and John Lutz, 21 June 2005.)

Lt. Philip L. “”Moki”” Martin corresponded with Captain Dry and was most helpful to the authors, as was Captain John D. Chamberlain, U.S. Navy (Retired). Lutz, the pilot of the SDV, also qualified his confidence in the craft. From his perspective the best one could expect from the Mark VII was to “”… aim, go, and look.”” The SDV was launched at the end of floodtide. As an aid to navigation most of the transit to the target was made on the surface at a 15-degree, bow-up attitude. As a result the SDV could only make three knots and, while contending with strong currents, was forced off course. With the SDV’s battery power depleting more rapidly than normal, the crew was forced to turn back prior to reaching their objective—but too late to reach the Grayback before power ran out.

ADJC John L. Wilson, the helicopter crew chief, provided numerous insights on the mission. Lutz, the second man to jump from the helicopter, also counted to four before hitting the water. The impact broke his web belt buckle. He believes the altitude of the drop was at least 50 feet. Edwards, the last man to jump, counted to four before hitting the water. In addition to breaking his ribs, the impact split his wet suit open and tore off his web belt. He remained unconscious for three hours and probably would have drowned if Martin had not found him.

According to the SDV’s UDT operators, Edwards and Lutz, the sub’s launch-and-recovery team reportedly directed the second SDV crew to add ballast prior to the launch to compensate for the strong current across the Grayback’s deck. Following its launch, the SDV immediately sank to the bottom. The craft’s purge pumps were unable to deal with the water-head pressure to bring the SDV back to operating depth. (E-mails to the authors from Edwards and Lutz in June 2005)

We also studied a naval message from CTU 78.12 to Commander, Seventh Fleet, DTG 060201Z Jun 1972, LOC PDS LC 92/302 reel 61 and received information from Edwin L. Towers on 16 February 2005.

We interviewed Col. Samuel E. Birky, U.S. Army, Fort Bragg, N.C. on 23 July 2004. Birky, a SEAL petty officer at the time of Operation Thunderhead, was firmly resolved not to be captured during the time he drifted alone—mindful that no SEAL has ever been captured or left behind by his teammates, whether killed or wounded, regardless of the intensity of enemy fire or numerical superiority during combat operations. In addition to Birky, the other occupants of the second SDV were Steve McConnell, the SDV driver, Lt. Bob Conger, and Lt. (j.g.) Tom McGrath.

Dry’s body was flown first to Da Nang and then to a U.S. Army mortuary at Tan Son Nhut Airbase in Saigon. There, it fell to another Naval Academy classmate, Lt. Benjamin F. Burgess III, to identify Dry’s remains. Burgess, an admiral’s aide and flag lieutenant stationed in Saigon, was one of Dry’s closest friends at the Academy.

A letter to Captain Dry from Capt. M.A. Horn, Commander Submarine Flotilla Seven, 10 June 1972, stated the official cause of death. In July 1972, Capt. Dry was provided a copy of the Navy’s death certificate stating his son died June 6, 1972, “”on board USS Grayback (LPSS-574) as a result of injuries sustained in an operational accident.””

Former Secretary of the Navy James H. Webb Jr., addressed the incident in “”Are Enough Names Enshrined in Memorial Hall,”” Shipmate, March 1999, p. 15.

Others who were familiar with the circumstances surrounding Dry’s death share similar views on his heroism. Lt. Cdr. Towers, the Seventh Fleet staff officer assigned to Operation Thunderhead and present in the helicopter on the night of Dry’s death, dedicated his 1981 account of the abortive rescue attempt to the young SEAL. “”His love of country and his commitment to the cause that those in captivity might have hope for freedom cost him his life,”” he wrote. In a letter to Capt. Dry in 1982, the Grayback’s commanding officer said, “”Your son died a hero to those who knew him; a deeply respected man with a superb professional reputation.”” In his June 27, 1972 letter of condolence to Dry’s parents, the chief of naval operations, commenting on their son’s efforts to preserve liberty and freedom in South Vietnam, wrote, “”Your son was one of those heroic Americans who answered that call.”” Petty Officer Richard C. Hetzell said that Dry was, “”… one of the best officers that the SEAL team ever had.”” Hetzell, one of the most experienced combat veterans in Dry’s platoon’s stated, “”Spence was a great leader and a friend, and I would have followed him to the gates of hell if he had asked me to.””

Captain Slattery, a naval special warfare officer and Vietnam combat veteran, teaches history and government at Campbell University in Buies Creek, North Carolina. Captain Peterson, a naval aviator and also a Vietnam veteran, is a senior technical director with the Anteon Corporation’s Center for Security Strategies and Operations and the North America editor of Naval Forces.

DRY, MELVIN SPENCE

- LT US NAVY

- VIETNAM

- DATE OF BIRTH: 03/13/1946

- DATE OF DEATH: 06/06/1972

- BURIED AT: SECTION 10 SITE 11332

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard