Medgar Wiley Evers was born at Decauter, Mississippi, on July 2, 1925.

He served in the United States Army during World War II, but was best know as a prominent civil rights leader in his home state.

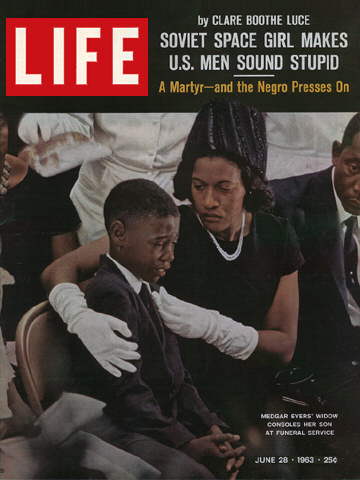

He was shot and killed outside his home at Jackson, Mississippi, on the evening of June 12, 1963 and was buried in Section 36 of Arlington National Cemetery one week later.

His story is portrayed in the motion picture, “The Ghosts of Mississippi.”

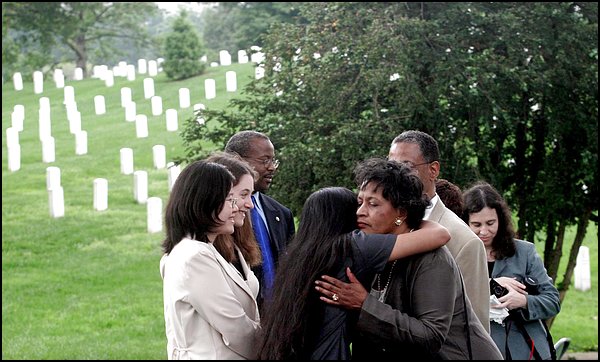

Some came with words of inspiration, others with expressions of congratulations, but all came to remember and celebrate a since-passed friend and civil-rights activist Medgar Evers.

The ceremony, at Arlington National Cemetery near Washington, commemorated the 40th anniversary of Evers’ death. The World War II veteran spent years building the civil-rights movement in Mississippi from the time he graduated from college in 1952 until his murder in 1963.

Evers’ wife, Myrlie Evers-Williams, spoke to a crowd of about 150 friends, family, high school students and dignitaries including Senator Trent Lott, R-Miss., Rep. Benny Thompson, D-Miss., and the Rev. Nelson B. Rivers III, chief operating officer for NAACP.

Evers-Williams recalled 40 years ago wiping a tear from her daughter’s face when the U.S. flag was folded and handed to them at Evers’ funeral in Arlington. She recalled the same trees, the same rustling of wind and the feeling and sense of peace.

“The taps played, a salute and the flag was presented,” Evers-Williams said. “It felt as if we were truly being treated as Americans.”

She said Evers did much to further the cause of equal rights and desegregation, but more work is still ahead. She encouraged young people to become active in promoting civil rights in America, and she commended three Illinois high school students for putting the ceremony together.

“I have so much respect for these three young women for putting this together,” Evers-Williams said. “They rose to the challenge and that speaks to the power of our young people, of our education.”

The students, 18-year-olds Debra Siegel and Xiaorang Wu, and 17-year-old Sharmistha Dev, started researching Evers and his accomplishments a year and a half ago as part of an extra-credit assignment for a history class at Adlai E. Stevenson High School in Lincolnshire, Ill.

“We are all very interested in civil rights but we’d never heard of him before,” Dev said. “We looked on the Internet and talked to people and it just snowballed from there.”

The girls’ history teacher, Barry Bradford, also addressed the audience.

“What was Medgar Evers all about?” Bradford said. “He believed this country needed change.”

Bradford related how Evers’ suspected assailant was greeted at his trial with a handshake by the then-governor of Mississippi, how all-white juries two times found him innocent, and how he was set free to go home to a welcoming parade. However, the assailant was convicted in February 1994 based on new evidence. Bradford reminded attendees that the killer died two years ago and had fewer than 20 people at his funeral. People from around the world would be remembering Evers and all he did for equality.

Bradford thanked Lott for attending and showing his support. “Lott didn’t agree with everything Medgar Evers said, but he’s told America that he was wrong, and it means a lot to have him here,” Bradford said.

Courtesy of the Washington Post, 17 June 2003

Civil Rights Project Turns Personal

Students Celebrate Medgar Evers in Documentary, Arlington Ceremony

Myrlie Evers-Williams gazed across Arlington National Cemetery yesterday and saw many of the same loving faces, the same graceful trees and the same plot of gently sloping earth she saw exactly 40 years ago, the day her husband Medgar Evers was buried. Only this time, the grave of the slain civil rights leader was a scene of celebration.

“We are not here mourning. We are not here to be sad. We have shed our tears,” she said, her voice measured as she spoke before a crowd of 200 that gathered to honor Evers’s legacy.

“I know that his memory will live on,” she told the crowd, and then cited as evidence for her optimism the three young women sitting in the front row: Debra Siegel, Sharmistha Dev and Xiaorong Wu.

The three, graduating seniors at Adlai E. Stevenson High School in suburban Chicago, were responsible for putting together yesterday’s ceremony. Their idea to honor Medgar Evers on the 40th anniversary of his burial began June 12, 2002, the 39th anniversary of his murder.

That muggy late spring day, the students, along with their history teacher, Barry Bradford, huddled beside the worn, understated and altogether ordinary white marble headstone that marks the final resting place of an extraordinary man.

“We all felt this incredibly strong urge to cry,” Wu said. “We didn’t talk at all. Silence seemed more appropriate.”

The four looked at the dates on the stone, noting that Evers, who was 37 when he was shot, had been dead for longer than he had been alive. They saw, too, that on this grim anniversary, they were the only ones there to pay tribute.

“It just hit us like a ton of bricks,” Siegel said. “It really made us all think about what we were doing.”

What they were doing was researching Medgar Evers’s life for a competition called National History Day. But already the project had taken on meaning far beyond the results of the contest.

Evers’s story touched them deeply.

They learned from Bradford how Evers struggled to bring racial equality to his home state of Mississippi; how he used civil disobedience to highlight the injustice of the violent segregationist system; and how, on June 12, 1963, Evers paid the ultimate price for his work when an assassin’s bullet struck him in the back.

A World War II veteran, he was buried at Arlington.

As the students and their teacher left the graveside last spring, they resolved to make sure that this year, Evers would get the attention he was due.

They went to work almost immediately, collecting information on Evers from every source they could find. They worked collaboratively but each had her specialty: Siegel, 18, focused on interviewing; Dev, a 17-year-old whose family emigrated from India when she was 5, edited; and Wu, an 18-year-old whose family emigrated from China when she was 3, handled much of the writing.

Their work was exhausting, and exhaustive.

“If you saw their bibliography, you’d think it was a master’s thesis,” Bradford said.

This spring, Bradford and the students told Evers-Williams about their plan to hold a ceremony honoring her late husband.

She responded that it sounded like a great idea but challenged them to organize it for themselves.

So that’s what they did.

Yesterday they fulfilled the promise they made a year ago. Among those attending the ceremony were civil rights activists, historians, students from Mississippi, television and print reporters and Evers family members.

Sitting in the front row beside the students and family was Senator Trent Lott (R-Mississippi), who had to resign as Senate majority leader six months ago, after making supportive comments about Strom Thurmond’s segregationist campaign for president in 1948.

Evers-Williams welcomed Lott, expanding on a theme of reconciliation that she said is at the heart of her husband’s legacy. She said Lott’s presence “speaks to the importance of at least talking to one another.”

“We have found ways to work with the system — and, yes, to work the system to our benefit,” Evers-Williams, a civil rights activist in her own right who recently served as chair of the NAACP, told the crowd.

When Medgar Evers was killed 40 years ago, working with the system was not an option — at least not in segregated Mississippi.

“The official state policy was to stop whatever it was he was doing,” Lawrence Guyot, a fellow Mississippi activist, said yesterday before his friend was honored. “There was no such thing as mutual ground or common ground. We fought for the right to fight in Mississippi.”

Yet Evers never resorted to violence, choosing instead to hold boycotts and to organize demonstrations for such basic things as voting rights. He was, as Evers-Williams said yesterday, “in the trenches,” always working for equality but never demanding publicity for himself.

Evers’s selflessness was part of what drew the attention of Bradford and his three students.

Bradford was 8 years old when Medgar Evers was killed, and the memory stuck with him. “I have kept the Medgar Evers story in my heart for many, many years,” he said.

When he became a teacher, he decided that Medgar Evers’s life would make a perfect research project for National History Day. But he wanted to do the project with the right students.

In Siegel, Dev and Wu, he knew he had found them. “They’re the most phenomenal students I have ever taught, not only in terms of their intellect but in terms of their humanity, their compassion and their integrity,” he said.

The students stayed late at school to dig through old legal files, called former prosecutors and traveled to Jackson, Miss., to interview some of those who had known Evers best, including his brother, Charles.

The students produced a documentary that will be judged for National History Day awards later in the week, but they said the biggest prize they could possibly receive was the one they got yesterday, when Evers-Williams told them that Medgar would have been proud of their work.

“We just wanted to do him justice,” Siegel said.

From a press report of 15 June 2003:

DECATUR, Mississippi – Forty years after Medgar Evers’ assassination, his widow would like him to be remembered not just as a leader in the early civil rights movement in Mississippi, but also as a champion of the basic rights of citizenship for all Americans.

The right to vote, the right to send their children to good schools and the right to live without fear and intimidation shouldn’t be taken for granted, Myrlie Evers-Williams said.

She’d also like people to remember Medgar Evers’ name.

Many history books focus on only a few stars of the civil rights movement — Rosa Parks, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X.

“It was so painful to see others mentioned and Medgar’s name very seldom mentioned; to see him a footnote in the history books; to see where he was associated only with Jackson, Mississippi; to see where he only was a person who was able to have a successful boycott,” Evers-Williams, 70, said last week.

Medgar Evers, field secretary of the state NAACP, was shot and killed by a white segregationist in the driveway of his Jackson home June 12, 1963. He was 37.

His wife spoke last week to an interracial crowd of about 800 in the tiny east central Mississippi town where her husband was born and raised.

“Medgar once said, ‘You can kill a man, but you can’t kill an idea,'” Governor Ronnie Musgrove told the gathering. “Because of his bravery, his focused desire to bring about positive change and his ideas, we are all better off today than we were four decades ago.”

On Monday, family members and dignitaries are scheduled to gather for a memorial service at Evers’ grave in Arlington National Cemetery outside Washington. Among those scheduled to attend are U.S. Senator Trent Lott, R-Miss., and U.S. Reps. Bennie Thompson, D-Miss., and Chip Pickering, R-Miss.

Evers was Mississippi NAACP field secretary from 1954 until he was killed. He was known for promoting black voter registration at a time when poll taxes, literacy tests and violence tried to prevent it. As a World War II veteran who had fought in France, Evers tried to register to vote in 1946 at the Newton County Courthouse in Decatur, only to be turned away by an angry white mob.

Officials announced last week that a historical marker will be put up outside the courthouse to honor Evers.

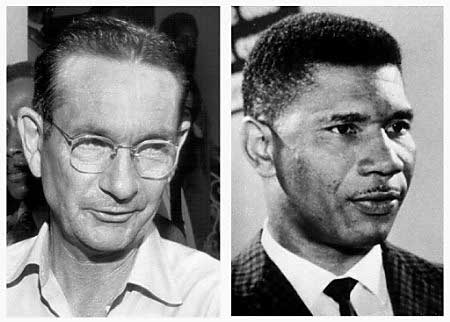

It took Mississippi 31 years to convict Evers’ killer.

Two all-white juries deadlocked in 1964, and segregationist Byron de la Beckwith walked free. Prosecutors reopened the case after new evidence was discovered in 1989. Beckwith was convicted of murder in 1994 and died in state custody in 2001.

The Rev. Nelson B. Rivers III, chief operating officer of the national NAACP noted how Mississippi’s political climate has changed. In 1964, then-Gov. Ross Barnett was photographed shaking hands with Beckwith in the courtroom during a break in the trial.

Rivers said Evers and others in the 1950s and 1960s reshaped society, and many young people today take freedom for granted.

“You don’t know what the back of the bus is,” Rivers said. “No ‘colored’ water fountains for you.”

Originally published August 14, 2002

By Gregory Kane

Courtesy of SunSpot.Net

36-1431

I make it a point to remember the numbers. The first one is the section in Arlington National Cemetery of the grave I want to visit. The last four are the numbers on the back of the headstone.

I arrive at the cemetery shortly after noon on another sweltering summer day in which the mercury would climb close to 100. I go straight to the information desk and pick up a visitors guide. I read the gravesites the folks at Arlington had bothered to highlight for tourists.

The guide tells me where I can find President John Kennedy and his brother, former Attorney General and U.S. Sen. Robert Kennedy. But I’m not here to see them. Not this day.

I’m here to visit the gravesite of one Medgar Wiley Evers, the first Mississippi field secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, who from 1954 – when he took the job – to 1963, when he took an assassin’s bullet in the back, waged a campaign to break the hold racists and segregationists had over his state.

But I don’t see his name on the visitors guide’s list of graves I might want to visit.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, the Supreme Court justice who once wrote of his “pleasure” in voting for the nationality of a law that permitted the forcible sterilization of a poor, powerless woman who was incorrectly classified as an “imbecile,” is listed. Recognition for Holmes, but none for the man who fought relentlessly for freedom in the closest thing America has had to a police state?

Sir John Dill, a World War II British field marshal, is on the list. The guide tells me where I can find the Confederate memorial at Arlington. A foreigner and a bunch of guys who fought to perpetuate slavery, but no mention of Evers?

“Is Medgar Evers buried here?” I ask the woman at the information desk.

“Yes, he is,” she answers and rifles through some index cards on the desk. After a few moments she writes down the section and headstone number for me and highlights area 36 on the map in the guide.

“Why isn’t his name listed in the visitors guide?” I query.

“It’ll probably be in the new one,” the woman answers. “They’re coming out with a new one in about a month. A lot of ’em end up buried here who turn out to be famous.”

“Do many people ask about him?”

“Oh, yeah. A lot of people ask about him.”

I take comfort in that. It’s not that there are no African-American gravesites listed in the visitor’s guide. Daniel “Chappie” James, the first black four-star Air Force general, and heavyweight boxing immortal Joe Louis are listed. But I’m the stubborn kind of cuss who figures that if you have a major figure from the civil rights movement buried at Arlington, you tell folks where to find his grave.

I tell myself maybe I’m too obsessed about this, almost fanatical, in the Churchillian sense, meaning I won’t change my mind and won’t change the subject. I tell myself I’ve read For Us, the Living – Myrlie Evers-Williams’ account of her life with Medgar – way too many times. I’m way too close to them both. To Medgar Evers, who died 39 years ago, and his widow, whom I don’t know, have never met and have spoken to only once during a phone conversation from her home in Bend, Oregon.

But then I remember what Evers-Williams told me in that brief interview.

“I have, for years,” she said, “either been hurt, angry or a complainer about Medgar not getting the credit for being a pioneer who paved the way for Martin [Luther King Jr.] and others.”

She’s right about that. Read For Us, the Living about how Medgar went boldly into Brookhaven, Mississippi, in 1955 after a black man named Lamar Smith was shot dead in broad daylight on the courthouse lawn for daring to vote. Evers went to investigate, as he did in dozens of beatings and murders of blacks throughout the state. Often, Evers-Williams wrote, he would send fugitives from Mississippi’s terrorism out of state with money from his meager funds.

I’m reminded of all this and conclude that only a very few of the more than 250,000 buried here had as much courage, determination and heroism as Medgar Wiley Evers. He deserves recognition from the folks at Arlington, who seem to have forgotten him.

But at his gravesite, visitors have left their own memorial. Some placed rocks on the headstone. Larger rocks and pebbles have been placed at the base, the better, perhaps, for folks to recognize the gravesite. Officials of this cemetery might have forgotten who you are, visitors seem to say, but we won’t.

The grave is 36-1431. You will visit it, won’t you?

From a press report: January 22, 2001

Byron De La Beckwith, a white supremacist who escaped justice for 31 years before being convicted in the 1963 murder of civil rights activist Medgar Evers, died late on Sunday night in a Jackson, Mississippi, hospital, a hospital spokeswoman said on Monday.

Beckwith, 80, was serving a life sentence at Central Mississippi Correctional Facility in Rankin County. He died just hours after he was taken to University Medical Center complaining of chest pains.

“I can confirm that he expired yesterday at 10:12 p.m. Mississippi time Monday,” hospital spokeswoman Barbara Austin said, adding it was not hospital policy to release the cause of death.

Beckwith, a retired fertilizer salesman and decorated Second World War veteran, was convicted in 1994 for the June 12, 1963, slaying of Evers, who was shot in the back as he walked up his driveway.

Evers, 37, had drawn the wrath of white supremacists for spearheading efforts by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to win equal rights for blacks in the once deeply segregated southern state.

All-white juries at two earlier trials were unable to reach verdicts in the case despite the discovery of Beckwith’s fingerprint on the deer rifle used to kill Evers.

Beckwith, who insisted he was 90 miles away in Greenwood, Mississippi, when Evers was murdered, would in the years following the mistrials brag to his friends about “beating the system.”

In 1967, Beckwith ran for lieutenant governor of Mississippi, finishing fifth with more than 34,000 votes. In 1973, he was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison for possessing dynamite without a permit.

He later moved with his wife to Signal Mountain, Tennessee, where he lived in relative obscurity as an ordained minister for the Christian Identity Movement, a white supremacist group.

Although many Mississippians would come to accept integration and subsequent efforts to extend equal rights to blacks, Beckwith, who once referred to Evers as a “mongrel,” would never desist from his racist views.

“He was stuck in time and just could not budge,” said Brad Bond, a professor of history at the University of Southern Mississippi, who described Beckwith as both a monstrous and tragic figure.

Beckwith continued to publicly deny killing Evers, but his explanations failed to sway a new generation of Mississippi prosecutors who reopened the case in 1989 at the prompting of Evers’ widow, former NAACP leader Myrlie Evers Williams.

Armed with new evidence and a 127-page document alleging numerous errors in the original trial, prosecutors had Beckwith arrested again on December 17, 1990. A jury of eight blacks and four whites found him guilty of murder following a two-week trial.

In 1997 the Mississippi Supreme Court upheld the conviction, which has led to the reopening of a number of 1960s civil rights crimes in the state.

Although now widely regarded as a crude villain for his assassination of Evers, Beckwith was wounded and awarded a Purple Heart for valor during the Battle of Tarawa during the Second World War.

In an ironic twist, it is Evers who lies buried in Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia, the resting place for many of the nation’s presidents and national heroes. Beckwith will likely be buried in Mississippi after an autopsy.

Navy to honor civil rights martyr Medgar Evers

October 2009

Slain civil rights leader Medgar Evers will be honored Friday with a Navy supply ship named for him.

Navy Secretary Ray Mabus, a former governor of Mississippi, planned to announce the honor during a speech at Jackson State University in Jackson, Mississippi. The nearly 700-foot-long vessel named for Evers will deliver food, ammunition and parts to other ships at sea.

During the civil rights movement Evers organized nonviolent protests, voter registration drives and boycotts in Mississippi, rising to the post of national field secretary for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

In 1963 Evers was assassinated in the driveway of his home in Jackson after returning from a meeting with NAACP lawyers. His death prompted President John F. Kennedy to ask Congress for a comprehensive civil rights bill.

Evers was born in Decatur, Miss., in 1925 and served in the Army during World War II. He returned to Mississippi, earned a degree from Alcorn College in 1952 and became active in the NAACP and its civil rights work in his home state.

Thirty-seven when he was shot to death by a white supremacist, Evers was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. His killer, Byron De La Beckwith, was not convicted until 1994.

“The selection of Medgar Evers … honors the pioneering spirit of the late civil rights activist from Mississippi who forever changed the face of race relations in the South,” according to an administration statement. “At a time when our country was wrestling with finally ending segregation and racial injustice, Evers led civil rights efforts to secure the right to vote for all African-Americans and to integrate public facilities, schools and restaurants.”

The Navy names ships in the support fleet to honor pioneers, explorers and other notables. The Navy ship honoring Evers is the first named for an African-American since President Barack Obama took office.

EVERS, MEDGAR WILEY

T/5 958 QM SVC CO QMC USA

- DATE OF BIRTH: 07/02/1925

- DATE OF DEATH: 06/12/1963

- BURIED AT: SECTION 36 SITE 1431

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard