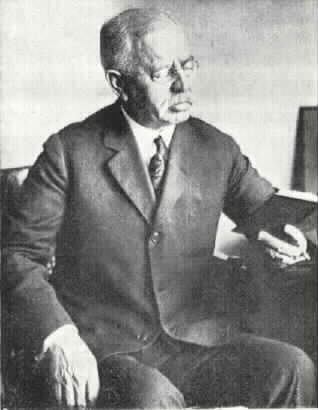

Courtesy of the Ahern Family

Lieutenant Colonel George Ahern

Forestry Expert Fought for Conservation of Woodland

WASHINGTON, May 13 (AP) – Lieutenant Colonel George P. Ahern, U. S. A., retired, died here today (13 May 1940) at the age of 82. He was graduated in 1882 from West Point.

Colonel Ahern served in Cuba and the Philippines during the war with Spain, and remained in the Philippines to organize and direct the Office of Patents, Copyrights, and Trade-Marks and later the Bureau of Forestry for the Philippine Government. He was the author of several books on forestry.

He was born in New York on December 29, 1859, the son of Patrick Henry Ahern and Ann Dwyer Ahern, who came to this country from Ireland. He was “a son of the Irish revolution,” in his own words. His father, who was in the dry goods business, was a flag bearer in the Battle of Bull Run.

His first active service was in the Indian campaigns in the Northwest. Chief Sitting Bull gave him the title of Chief Two Crows for his kindness in dealing with the Indians. He had a lasting empathy for the Indians and unceasingly endeavored to obtain justice for them in Washington. — The New York Times 14 May 1942.

Col. George P. Ahearn [sic]

On Wednesday, May 13, 1942, COL. GEORGE P. AHEARN, U. S. A., retired, beloved husband of Jean Gill Ahearn. Remains resting at the S. H. Hines Co. funeral home, 2901 14th St., nw, until 2 p. m. Friday May 15. Funeral service at Fort Myer Chapel, Fort Myer, Virginia, on Friday, May 15, at 3 p.m. Interment Arlington National Cemetery. — The Washington Post 14 May 1942.

Place Names of Glacier/Waterton National Parks

by Jack Halterman

Glacier Natural History Association

Ahern Creek, Glacier, Pass and Peak are named for Lt. George Ahern, who conducted what must have been the most extensive (and intensive) of the early explorations of the Glacier Park country. Born in 1859 of parents who had come from Ireland, he grew up in the rough-tough streets of East Side Manhattan, yet somehow he made it to both Yale and West Point. At the Academy he was admitted in 1878 and graduated in ’82, the lowest in his class of 37. He had the typical Irish good looks, red hair and sprightly good humor, and his Army nickname was Patsy — a strange name for a slum kid.

He had some role in the Sioux wars and served as secretary for Sitting Bull. While he was stationed at Fort Shaw, Montana, he made two of three ventures toward and into the area of modern Glacier Park, leading black infantrymen in the quest for a pass over the Continental Divide in 1888, perhaps in 1889, and again in 1890. In these years he married Jean Gill.

In August of ’90 Ahern and a few black troopers of the 25th Infantry were accompanied by G. E. Culver, a naturalist from the University of Wisconsin, and other civilians — a packer Indian guides and prospectors (with both Louis Meyer and Joe Cosley probably among them). They explored Cut Bank Creek, Milk River (or Hudson’s Bay) Ridge, and Swiftcurrent Creek. With selected companions, Ahern made at least three side-trips to the Continental Divide. From the Canadian line they turned, came up Belly River, had a friendly meeting with some Stoney Indians, and finally crossed the forbidding Ahern Pass — a route fit only for “a crazy man”. Then followed another side-trip into the Waterton country, then one to Lake McDonald, Camas Creek, the North Fork, and the Flathead Valley. Presumably, there was a rendezvouz at Demersville with another group of the 25th Infantry.

Although still in the Army, Ahern acquired a deep interest in forestry and conservation, made lecture tours through Montana, helped create the Fish, Game, and Forestry Commission, and taught pioneering classes in forestry at the College of Agriculture in Bozeman. With his friend Gifford Pinchot, he explored the Bitterroot and Clearwater wilderness in 1895, helping to form this area into a national forest. Though encouraged by Pinchot, he was checkmated by the powerful mining and timber corporations, particularly by Senator Carter. He denounced the greed with which the corporations were “gutting the mountains”.

In 1898 Ahern landed troops under fire at Tayabacao, Cuba, and for this exploit was eventually cited for gallantry in action. Transferred to the Philippines, he was appointed by Pinchot as head of the Philippine Bureau of Forestry, a post he held for fourteen years. On Bataan Peninsula he established the Philippine Forest School. From Manila he and Pinchot set out on a cruise of 2000 miles among the islands to make a study of forests, then extended their cruise to Nagasaki and Yokohama, Japan.

Retiring in 1906, Ahern returned to active duty in 1916, serving in the War College in Washington and at the Veteran’s Bureau. He retired again as a Lt. Colonel in 1930, died in Washington, D. C. at the age of 82, and is interred at Arlington. A remarkably kind and courageous man, he left a record of service hardly equalled by anyone else mentioned in these pages.

Ahern Pass has long been known as one of the most dangerous in Glacier Park, but it was used by surveyor Sargent and packer Frank Valentine, and Joe Cosley made it a favorite escape route into his Belly River refuge. Once Joe’s two horses slipped on the ice of the pass and hurtled a thousand feet into the abyss. The Blood Indian name for the pass is Saóix ozitamisohpi(iaw): The warriors where they go up (or West). The name for the glacier is Sisukkokutui: Spotted Ice.

George Ahern’s wife, Jean Gill Ahern, for whom he had once named the lake now called Elizabeth, survived her husband by several years. Since he was interred in Arlington Cemetery on 15 March 1942, she was interred there in 1948.

“Again, in 1890, another army detachment, under Lieutenant George P. Ahern, then stationed at Fort Shaw, was ordered to explore the mountains along the Canadian border. The party consisted of Ahern, a detachment of negro soldiers from the 25th Infantry, Professor G. E. Culver of the Uiversity of Wisconsin, two experienced mountaneers (packer and guide respectively), two prospectors, two Indian guides, and the pack train. The party left Fort Shaw on August 5, crossed the prairies, and finally reached the foot of the mountains near Cut Bank Creek. From there they went north to the International Boundary, thence up the Belly River toward the pass that later was named for Lieutenant Ahern.

Upon reaching this pass, the entire party worked for two days making a trail from the foot of the talus slope to the summit, completing the first of two known successful trips with pack stock over present Ahern Pass. (The second trip was by R. H. Sargent of the U. S. Geological Survey, in 1913.) Because the western slope of the pass was heavily timbered, they had difficulty cutting their way through; nor was this helped by the fact that most of the trip was accomplished in pouring rain.

Upon reaching McDonald Creek the Ahern party turned up the creek for some distance, then crossed over into Camas Creek Valley, probably in the vicinity of the present Heaven’s Peak Lookout Trail. From there they traveled down Camas Creek (which he calls “Mud Creek” on his map) to the valley of the North Fork of the Flathead River, where they swung back toward Lake McDonald, presumably about the route of the present North Fork Truck Trail, and proceeded down the Flathead River to the Flathead Valley.

On this journey, side trips were made up Cut Bank Creek to the summit; up Swiftcurrent Valley or St.Mary Valley (the records are not clear on this), to the summit; and over the divide from McDonald Creek into the headwaters of the Waterton Valley. The complaints of some present-day “dude” parties about bad trail conditions seem silly in the face of the difficulties faced by these men who had to cut a route through a virgin forest and in many instances built trail to get their stock through. To fully appreciate this, one would have to attempt taking loaded pack stock cross-country from Ahern Pass to Camas Creek today — a feat that modern packers would term practically impossible!” — Montana: The Magazine of Western History July 1957

“The ROTC program started at Montana State University in 1896 with a parade of 40 cadets participating in a ceremony during which the Governor of Montana laid the cornerstone of Montana Hall. Professor William M. Cobleigh was the first Professor of Military Science, in addition to his primary job of college professor. Army Lieutenant George P. Ahern arrived shortly thereafter, and served as the PMS during 1897 and 1898. During this period the ROTC Department received the Model Springfield rifles and two artillery pieces. Lt. Ahern taught courses in basic Military Science and Tactics and insured that all cadets fired all military weapons available.

At the outbreak of the Spanish-American War in 1889, Captain (newly promoted) Ahern was called back to Regular Army service, leaving a void in ROTC instructors at MSU for 18 years.”

— History of the ROTC at Montana State University

“Officers did not have to find themselves stationed at universities to partake of the educational opportunities available in many urban areas, and the ways officers became involved in civilian communities were as varied as the personalities of the individuals concerned. Pershing’s friend and classmate, Avery D. Andrews, attended law school in Washington, D.C., while on assignment with the War Department, and George P. Ahern, on recruiting duty in the East, enrolled in the senior class of the Yale Law School, completing a thesis on “The Necessity for Forestry Legislation” before returning to his regiment in Montana, where he used whatever spare time he could muster to spread the gospel of conservation before representatives of mining and lumbering interests. Even isolation in Montana did not prevent Ahern from maintaining contact with influential foresters in the East such as Gifford Pinchot and Bernard Fernow.” — The U.S. Army and Irregular Warfare: Progressives in Uniform by John M. Gates

[Major] George P. Ahern, 25th Infantry, in charge of Sitting Bull’s mail, describes him as “a very remarkable man — such a vivid personality . . . square-shouldered, deep-chested, fine head, and the manner of a man who knew his ground. He looked squarely into your eyes, and spoke deliberately and forcefully. . . . For several months I was in daily contact with Sitting Bull, and learned to admire him for his many fine qualities. He would visit me in my quarters when I failed to show up in camp. He would enjoy leaving his card; in fact it was my card which I had purposely left in his tipi, and he would return itwith his own name written on the reverse side. The nearest he came to being jovial was when he dropped the card on my table with a smile and a twinkle in his eye. . . . Even then I had become acquainted through older officers with some of the great wrongs done the Indian, and I marvelled at the Indian’s patience and forbearance!” — Sitting Bull; Champion of the Sioux by Stanley Vestal

“Ever since 1882 there has been gross and continuous mismanagement of Indian affairs. . . . This able, brilliant people was crushed, held down, moved from place to place, cheated, lied to, given the lowest types of schools and teachers, and kept always under the heel of a tyrannical Bureau.” — Lieutenant Colonel George P. Ahern, U. S. A., Retired

While on bivouac with the Twenty-Fifth Infantry near Fort Keogh, Montana, during the Pine Ridge Campaign, Lieutenant G. P. Ahern wrote a local newspaper:

We have a strong force of infantry and cavalry here on the northwest corner of the war. Our ‘cullud’ battalion here is under canvas and in fine shape for a winter campaign, and when Jack Frost freezes the mercury out of sight the gay and festive coon will be found ready to dance the ‘Virginia essence’ and sing as joyfully as ever.” — Stock Growers Journal (Miles City, Montana) December 17, 1890.

Trying to trace the ancestry of Jean Gill who married George Patrick Ahern about 1889, possibly while he was stationed at Fort Shaw in the Montana Territory as a Lieutenant in the 25th Infantry. Her father was reputed to have been a Confederate General in the Civil War. She died in 1948 and is buried with her husband in Arlington National Cemetery. Lt. Ahern led an expedition to explore what became Glacier National Park and named a lake after his wife, but it was later renamed. Click here for more information on Ahern.

I have found reference to a Lt. William G. Gill, graduate of West Point, who resigned from the U. S. Army to join the Confederacy, but I don’t know if this is Jean’s father or not.

AHERN, GEORGE P

- LT COL USARMY RETIRED

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: Unknown

- DATE OF DEATH: 05/13/1942

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 05/15/1942

- BURIED AT: SECTION 4 SITE 3050

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

AHERN, JEAN GILL

- DATE OF DEATH: 11/14/1946

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 11/17/1946

- BURIED AT: SECTION 4 SITE 3050

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard