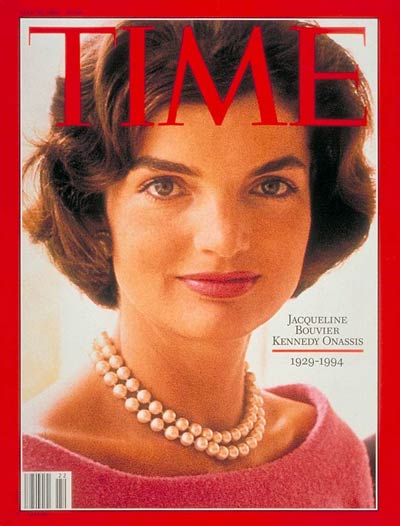

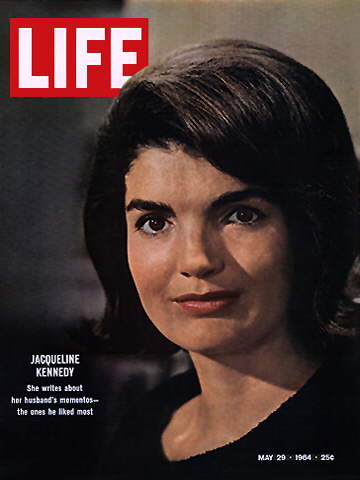

The wife of John Fitzgerald Kennedy, she married Greek financier Onassis several years after JFK’s death in 1963. She became a widow the a second time when Onassis died and was again single when she died of cancer in 1994. Due to this status, she was laid to rest next to JFK and their two infant children in Arlington National Cemetery.

From a contemporary press report

Tuesday, May 24, 1994

ONCE MORE, A SERVICE IN ARLINGTON MRS. ONASSIS LAID TO REST BESIDE THE ETERNAL FLAME

IN THE END, she came back. It didn’t matter, anymore, that her name had become the awkward, at first unfamiliar Jacqueline Onassis. It didn’t matter that she’d tried to hide from our hungry curiosity and awed adoration behind the new wealth, the new career, or under the sunglasses and the kerchief.

What mattered on Monday was that the grave of this intensely private woman would be in one of the most public places in America: Arlington National Cemetery, atop a sweetly sloping green hill, near a red-gold sliver of flame, beside the husband with whom she helped create a magic myth and the two babies who also had died too young. What mattered was that we knew who we were burying:

Jackie Kennedy.

In death, as we had in life, we could make of her what we wanted her to be. Maybe what we needed her to be.

It was somehow exactly right on Monday that the way most of us saw her burial in Arlington Cemetery next to President John F. Kennedy was through the lens of a television camera.

That was how we had come to know her in the first place, as the doe-eyed brunette with the fawn-soft voice guiding us through the White House, as the elegant First Lady in her pillbox hats and white gloves, as the young wife who had perfected the look of smiling adoration at her dashing young resident long before Nancy Reagan appeared on the scene.

At her funeral in New York, the cameras outside St. Ignatius Loyola Church showed us only the somber crowd of spectators on the street. In Arlington, the lens peered down the slope, over the row of clipped bushes and into the granite bowl that Jackie had helped design as President Kennedy’s gravesite.

The granite bowl is a haunted place, but it isn’t quiet. Birds chitter loudly and full of life in the nearby magnolia trees. The microphones broadcasting her burial service picked them up clearly, along with a few snuffles from the family and friends gathered around what to them is an all-too familiar site.

They had been here to bury Jackie and Jack’s prematurely born son, Patrick Bouvier. Four months later, they buried his father, the nation’s president. A stillborn daughter was brought to lie in what would become a family cemetery for the Kennedys.

Five years later, they buried Robert F. Kennedy, also assassinated. After the burial service for Jackie, many of the mourners stopped to pay their respects at the other graves.

For many, that brief service must have seemed like time had somehow played a strange trick. At the podium a handsome man, John Kennedy Jr., read from the New Testament as a tribute to his mother. We remember him as John-John, a forlorn little figure saluting his father’s casket.

And it was Caroline Kennedy Schlossberg, the sugar-plum fairy-princess as a girl, who now wore a black veil to lead the mourners in a responsive liturgy from the 121st Psalm.

“I will lift up mine eyes to the hills,” she read. And outside the cemetery’s gates, hundreds of strangers were doing just that. Except they didn’t think of themselves as strangers.

Elizabeth Stephens had spent all night as a college sophomore standing in line to pass by John F. Kennedy’s casket. She had admired everything about Jackie, from her taste to her public silence in the first days of her grief and the years since. “It was another form of courage,” said Stephens.

For Jackie, she had brought a bouquet, a summary in flowers of much about the former First Lady: A white peony, the first from Stephens’ garden, because she had read it was Jackie’s favorite. Apricot irises, to match the color of a gown in one of Jackie’s portraits. All tied up in a “French” blue ribbon, because Jackie had loved France and was, after all, a Bouvier.

The day itself could have been ordered right out of Camelot. The air smelled of freshly mown grass and honeysuckle. There was a powdery blue sky, honey-colored sun, and a cooling breeze to fan the heat-flushed faces and make tears feel chilly on the cheeks.

Beth Alexiou dabbed at hers with a tissue and talked of how it was her “respect” for Jackie that brought her to the burial. The funeral procession had been a black blur of hearse and limousines speeding past.

Alexiou would see nothing more than that. Still, she had to come. Like many others, she too had been at JFK’s funeral. This brought the mourning full circle for both the slain president and his widow.

“They gave us what we needed at the time,” said Alexiou, who is now 55. “They woke us up to politics, to humanity.”

Jackie had been a role model for her, she said. She had followed her life after the White House, through the marriage with Aristotle Onassis.

In the end, it meant a lot to Beth Alexiou, to Elizabeth Stephens, to others outside the gate and across the country that Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis had come back to this place.

“This is her place,” said Alexiou. “There is no other place for her to be.”

May 20, 1994

But the disease, which attacks the lymph nodes, an important component of the body’s immune system, grew progressively worse. Mrs. Onassis entered the New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center for the last time on Monday but returned to her Fifth Avenue apartment on Wednesday after her doctors said there was no more they could do.

In recent years Mrs. Onassis had lived quietly but not in seclusion, working at Doubleday; joining efforts to preserve historic New York buildings; spending time with her son, daughter and grandchildren; jogging in Central Park; getting away to her estates in New Jersey, at Hyannis, Mass., and on Martha’s Vineyard, and going about town with Maurice Tempelsman, a financier who had become her closest companion.

She almost never granted interviews on her past — the last was nearly 30 years ago — and for decades she had not spoken publicly about Mr. Kennedy, his Presidency or their marriage.

Mrs. Onassis was surrounded by friends and family since she returned home from the hospital on Wednesday. After she died at 10:15 P.M. on Thursday, Senator Edward M. Kennedy’s office issued a statement saying: “Jackie was part of our family and part of our hearts for 40 wonderful and unforgettable years, and she will never really leave us.”

President Clinton said he and his wife, Hillary Rodham Clinton, spoke with Mrs. Onassis over the last several days and had been getting regular updates on her condition.

“She’s been quite wonderful to my wife, to my daughter and to all of us,” Mr. Clinton said.

Although she was one of the world’s most famous women — an object of fascination to generations of Americans and the subject of countless articles and books that re-explored the myths and realities of the Kennedy years, the terrible images of the President’s 1963 assassination in Dallas, and her made-for-tabloids marriage to the wealthy Mr. Onassis — she was a quintessentially private person, poised and glamorous, but shy and aloof.

They were qualities that spoke of her upbringing in the wealthy and fiercely independent Bouvier and Auchincloss families, of mansion life in East Hampton and Newport, commodious apartments in New York and Paris, of Miss Porter’s finishing school and Vassar College and circles that valued a woman’s skill with a verse-pen or a watercolor brush, at the reins of a chestnut mare or the center of a whirling charity cotillion.

She was only 23, working as an inquiring photographer for a Washington newspaper and taking in the capital night life of restaurants and parties, when she met John F. Kennedy, the young bachelor Congressman from Massachusetts, at a dinner party in 1952. She thought him quixotic after he told her he intended to become President.

But a year later, after Mr. Kennedy had won a seat in the United States Senate and was already being discussed as a Presidential possibility, they were married at Newport, R.I., in the social event of 1953, a union of powerful and wealthy Roman Catholic families whose scions were handsome, charming, trendy and smart. It was a whiff of American royalty.

And after Mr. Kennedy won the Presidency in 1960, there were a thousand days that seemed to raise up a nation mired in the cold war. There were babies in the White House for the first time in this century, and Jackie Kennedy, the vivacious young mother who showed little interest in the nuances of politics, busily transformed her new home into a place of elegance and culture.

She set up a White House fine arts commission, hired a White House curator and redecorated the mansion with early 19th Century furnishings, museum quality paintings and objets d’art, creating a sumptuous celebration of Americana that 56 million television viewers saw in 1961 as the First Lady, inviting America in, gave a guided tour broadcast by the three television networks.

A Transformation At the White House

“She really was the one who made over the White House into a living stage — not a museum — but a stage where American history and art were displayed,” said Hugh Sidey, who was a White House correspondent for Time magazine at the time. He said she told him: “I want to restore the White House to its original glory.”

There was more. She brought in a French chef and threw elegant and memorable parties. The guest lists went beyond prime ministers and potentates to Nobel laureates and distinguished artists, musicians and intellectuals.

Americans gradually became familiar with the whispering, intimate quality of her voice, with the head scarf and dark glasses at the taffrail of Honey Fitz on a summer evening on the Potomac, with the bouffant hair and formal smile for

the Rose Garden and the barefoot romp with her children on a Cape Cod beach.

There was an avalanche of articles and television programs on her fashion choices, her hair styles, her tastes in art, music and literature, and on her travels with the President across the nation and to Europe. On a visit to New York, she spoke Spanish in East Harlem and French in a Haitian neighborhood.

Arriving in France, a stunning understated figure in her pillbox hat and wool coat as she rode with the President in an open car, she enthralled crowds that chanted “Vive Jacqui” on the road to Paris, and later, in an evening gown at a dinner at Versailles, she mesmerized the austere Charles de Gaulle.

When the state visit ended, a bemused President Kennedy said: “I am the man who accompanied Jacqueline Kennedy to Paris — and I have enjoyed it.”

But the images of Mrs. Kennedy that burned most deeply were those in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963: her lunge across the open limousine as the assassin’s bullets struck, the Schiaparelli pink suit stained with her husband’s blood, her gaunt stunned face in the blur of the speeding motorcade, and the anguish later at Parkland Memorial Hospital as the doctors gave way to the priest and a new era.

In the aftermath, some things were not so readily apparent: her refusal to change clothes on the flight back to Washington to let Americans see the blood; her refusal to take sleeping pills that might dull her capacity to arrange the funeral, whose planning she dominated. She stipulated the riderless horse in the procession and the eternal flame by the grave at Arlington.

And in public, what the world saw was a figure of admirable self-control, a black-veiled widow who walked beside the coffin to the tolling drums with her head up, who reminded 3-year-old John Jr. to salute at the service and who looked with solemn dignity upon the proceedings. She was 34 years old.

A week later, it was Mrs. Kennedy who bestowed the epitaph of Camelot upon a Kennedy Presidency, which, while deeply flawed in the minds of many political analysts and ordinary citizens, had for many Americans come to represent something magical and mythical. It happened in an interview Mrs. Kennedy herself requested with Theodore H. White, the reporter-author and Kennedy confidant who was then writing for Life magazine.

The conversation, he said in a 1978 book, “In Search of History,” swung between history and her husband’s death, and while none of J.F.K.’s political shortcomings were mentioned — stories about his liaisons with women were known only to insiders at the time — Mrs. Kennedy seemed determined to “rescue Jack from all these ‘bitter people’ who were going to write about him in history.”

She told him that the title song of the musical “Camelot” had become “an obsession with me” lately. She said that at night before bedtime, her husband had often played it, or asked her to play it, on an old Victrola in their bedroom. Mr. White quoted her as saying:

“And the song he loved most came at the very end of this record, the last side of Camelot, sad Camelot. . . . ‘Don’t let it be forgot, that once there was a spot, for one brief shining moment that was known as Camelot.’

“. . . There’ll never be another Camelot again.”

Mr. White recalled: “So the epitaph on the Kennedy Administration became Camelot — a magic moment in American history, when gallant men danced with beautiful women, when great deeds were done, when artists, writers and poets met at the White House and the barbarians beyond the walls were held back.”

But Mr. White, an admirer of Mr. Kennedy, added that her characterization was a misreading of history and that the Kennedy Camelot never existed, though it was a time when reason was brought to bear on public issues and the Kennedy people were “more often right than wrong and astonishingly incorruptible.”

Five years later, with images of her as the grieving widow faded but with Americans still curious about her life and conduct, Mrs. Kennedy, who had moved to New York to be near family and friends and had gotten into legal disputes with photographers and writers portraying her activities, shattered her almost saintly image by announcing plans to marry Mr. Onassis.

It was a field day for the tabloids, a shock to members of her own family and a puzzlement to the public, given Camelot-Kennedy mystique. The prospective bridegroom was much shorter, and more than 28 years older, a canny businessman and not even American. Moreover, her brother-in-law, Robert Kennedy, had been assassinated earlier in the year, and the prospective marriage even posed a problem for the Vatican, which hinted that Mrs. Kennedy might become a public sinner.

Negotiating A Marriage

There were additional unseemly details — a prenuptial agreement that covered money and property and children. But they were married in 1968, and for a time the world saw a new, more outgoing Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. But within a few years there were reported fights over money and other matters and accounts that each was being seen in the company of others.

While the couple was never divorced, the marriage was widely regarded as over long before Mr. Onassis died in 1975, leaving her a widow for the second time.

Jacqueline Bouvier was born on July 28, 1929, in East Hampton, L.I., to John Vernou Bouvier 3d and Janet Lee Bouvier. A sister, Caroline, known as Lee, was born four years later. From the beginning, the girls knew the trappings and appearances of considerable wealth. Their Long Island estate was called Lasata, an Indian word meaning place of peace. There was also a spacious family apartment at 765 Park Avenue, near 72d Street, in Manhattan.

Although the family lived well during the Depression, Mr. Bouvier’s fortunes in the stock market rose and fell after huge losses in the crash of 1929. The marriage also foundered. In 1936, Mr. and Mrs. Bouvier separated, and their divorce became final in 1940.

In June 1942, Mrs. Bouvier married Hugh D. Auchincloss, who, like Mr. Bouvier, was a stockbroker. Mr. Auchincloss had been substantially better able to weather the Great Depression; his mother and benefactor was the former Emma Brewster Jennings, daughter of Oliver Jennings, a founder of Standard Oil with John D. Rockefeller.

From her earliest days, Jacqueline Bouvier attracted attention, as much for her intelligence as for her beauty. John H. Davis, a cousin who wrote “The Bouviers,” a family history, in 1993, described her as a young woman who outwardly seemed to conform to social norms. But he wrote that she possessed a “fiercely independent inner life which she shared with few people and would one day be partly responsible for her enormous success.”

Mr. Davis said Jacqueline “displayed an originality, a perspicacity,” that set her apart, that she wrote credible verse, painted and became “an exceptionally gifted equestrienne.” She also “possessed a mysterious authority, even as a teen-ager, that would compel people to do her bidding,” he said.

Jacqueline seemed shy with individuals but would flower in large groups, dazzling people. “It was this watertight, interior suffisance, coupled with a need for attention, and corresponding love of being at center stage, which puzzled her relatives so and which in time would alternately charm and perplex the world,” Mr. Davis wrote.

Her natural gifts could not save her from the effects of her parents’ divorce, and after it occurred, Mr. Davis said, her relatives noticed her “tendency to withdraw frequently into a private world of her own.”

John Vernou Bouvier Jr., her grandfather, wrote a history of the Bouvier family called “Our Forebears.” The history indicates that the Bouviers were descended from French nobility. Stephen Birmingham, who wrote the biography “Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis” (Grosset & Dunlap), called the grandfather’s book “a work of massive self-deception.” Mr. Davis called it “a wishful history.” From the documentation at hand, the Bouviers, who originated in southern France, had apparently been drapers, tailors, glovers, farmers and even domestic servants. The very name Bouvier means cowherd.

The family’s original immigrant, Michel Bouvier, left a troubled France in 1815 after serving in Napoleon’s defeated army and settled in Philadelphia. A man of considerable industry, he started as a handyman and later became a furniture manufacturer and, finally, a land speculator.

After the divorce, Jacqueline remained in touch with her father, but later she also spent a great deal of time with the Auchinclosses, who had a large estate in Virginia called Merrywood and another in Newport, R.I., called Hammersmith Farm. When she was 15, Jacqueline picked Miss Porter’s School in Farmington, Conn., an institution that in addition to its academic offerings emphasized good manners and the art of conversation. Its students simply called it Farmington.

She became popular with classmates as well as with young men who visited Farmington from Hotchkiss, Choate, St. Paul’s and other elite preparatory schools in the Northeast. Her teachers regarded her as an outstanding girl, but she once fretted to a friend, “I’m sure no one will ever marry me, and I’ll end up being a housemother at Farmington.” When she graduated, her yearbook said her ambition in life was “not to be a housewife.”

Just as Jacqueline picked Miss Porter’s, she also picked Vassar College, which she entered in 1947, not long after she was named “Debutante of the Year” by Igor Cassini, who wrote for the Hearst newspapers under the byline Cholly Knickerbocker. He described her as a “regal brunette who has classic features and the daintiness of Dresden porcelain.” He noted that the popular Miss Bouvier had “poise, is soft-spoken and intelligent, everything the leading debutante should be.”

Romance With Paris Starts in College

She did well at Vassar, especially in courses on the history of religion and Shakespeare, and made the dean’s list. The late Charlotte Curtis, who became society editor of The New York Times and who was a student at Vassar with Miss Bouvier, once wrote that Miss Bouvier was not particularly thrilled with being in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., and referred to her college as “that damned Vassar,” even though the invitations continued to flow in from young men at Harvard, Yale, Princeton and other leading universities. In 1949, for her junior year, she decided to apply to a program at Smith College for a year studying in France.

She loved Paris, and when the year was up she decided not to return to Vassar to finish her bachelor’s degree but to transfer to George Washington University in Washington. If this new institution lacked some of the elan and elegance of Vassar, its saving grace in her eyes was its location, in the capital. She received a bachelor’s degree from George Washington University in 1951.

While she was finishing the work for her degree, she won Vogue magazine’s Prix de Paris contest, with an essay on “People I Wish I Had Known,” beating out 1,279 other contestants. Her subjects were Oscar Wilde, Charles Baudelaire and Sergei Diaghilev. Her victory entitled her to spend some time in Paris, writing about fashion for Vogue, but she was persuaded not to accept the prize.

C. David Heymann, author of “A Woman Named Jackie” (Lyle Stuart, 1989) said Hugh Auchincloss had feared that if Jacqueline had returned to Paris and stayed there for any length of time, she might not have ever returned to the United States. Her mother came to agree with him. They may have been right; Mrs. Onassis would later recall her stay in Paris as a young woman as “the high point in my life, my happiest and most carefree year.”

In Washington, she met and was briefly engaged to John Husted, a stockbroker. Through her stepfather’s contacts, she was able to get a job as a photographer at The Washington Times-Herald, earning $42.50 a week. At the paper, she was an inquiring photographer assigned to do a light feature in which people were asked about a topic of the day; their comments appeared with their photos. Among the questions she asked were: “Are men braver than women in the dental chair?” and, “Do you think a wife should let her husband think he’s smarter than she is?”

She continued her work for The Washington Times-Herald and she enjoyed Washington’s restaurants and parties. It was at one such party, given in May 1952 by Charles Bartlett, Washington correspondent for The Chattanooga Times, that she met Mr. Kennedy, who would soon capture the Senate seat held by Henry Cabot Lodge.

Some time afterward, they began seeing each other, and the courtship gathered momentum. In 1953, while she was in London on assignment, Mr. Kennedy called her and proposed. Their engagement was not immediately made public by the Kennedys who feared that it might have headed off a flattering article due to appear in the Saturday Evening Post entitled, “Jack Kennedy — Senate’s Gay Young Bachelor.” The article appeared in the June 13 issue and the engagement was announced on June 25. They were married Sept. 12, 1953, at Hammersmith Farm in Newport.

John Bouvier, whose feelings about Mr. Auchincloss had been restrained, did not show up at the wedding, and the bride was given away by Mr. Auchincloss. The couple honeymooned in a villa overlooking Acapulco Bay in Mexico. She later wrote a long letter to her father, forgiving him, but he became withdrawn in the years that followed. He died in 1957.

In the late 1950’s, Mrs. Kennedy confided to friends that she tired of listening to “all these boring politicians,” Mr. Heymann wrote, but she did her duty as the wife of a Senator. There were trials in her personal life. In 1955 she suffered a miscarriage, and in 1956 she had a stillborn child by Caesarean section. Mr. Kennedy, who had only narrowly missed winning the Democratic Vice Presidential nomination in 1956, began to worry that they might not be able to have children. They moved into a rented Georgetown home after Mr. Kennedy sold his Virginia home to his brother, Robert. But in 1957 Caroline Bouvier Kennedy was born. Three years later she gave birth to John F. Kennedy Jr. A third child, Patrick Bouvier Kennedy, lived only 39 hours and died less than four months before President Kennedy’s assassination in 1963.

The Royal Aura Of the Kennedys

After Mr. Kennedy was elected President in 1960, the mystique and aura around Mrs. Kennedy began to grow rapidly, especially after she and her husband made the state visit to France in 1961.

Her elegance and fluency in French captured their hearts, and at a glittering dinner at Versailles she seemed to quite mesmerize President de Gaulle, a man not easy to mesmerize, as well as several hundred exuberant French people named Bouvier, all of them apparently claiming some sort of cousinhood. At a luncheon at the Elysee Palace, Theordore C. Sorensen wrote in “Kennedy” that President de Gaulle had turned to Mr. Kennedy and said, “Your wife knows more French history than any French woman.”

Returning home by way of London, where she received more approbation, Mrs. Kennedy soon began to make her plans to redecorate the White House, a building that she found lacking in grace. She asked the advice of Henry Francis du Pont, curator of the Winterthur Museum in Wilmington, Del., and set about collecting authentic pieces from the early 1800’s. She found some objects in the White House basement; others were donated by private citizens who, like Mrs. Kennedy, were interested in the project.

Some people said she went too far when she found some antique Zuber wallpaper on a wall in nearby Maryland, had it removed and rehung in the White House at a cost of $12,500, even though the original French printing blocks were still in existence and she could have had the same design on new paper for much less.

The social skills she acquired at East Hampton and Farmington were much in evidence. Her parties were nothing short of spectacular. When the president of Pakistan visited Washington, he heard an orchestra, took a boat ride, and had poulet chasseur, accompanied by couronne de riz Clamart and, for dessert, some framboises a la creme Chantilly at a table graced by silverware, glassware and china from Tiffany and Bonwit Teller.

Operatic and popular voices, the cello of Pablo Casals, string trios and quartets and whole orchestras filled the rooms with glorious sound.

“I think she cast a particular spell over the White House that has not been equaled,” said Benjamin C. Bradlee, former executive editor of The Washington Post, who was a friend of the Kennedys. “She was young. My God, she was young. She had great taste, a sense of culture, an understanding of art. She brought people like Andre Malraux to the White House who never would have gone there. As personalities, they really transformed the city.”

Letitia Baldridge, who was Mrs. Kennedy’s chief of staff and social secretary in the White House, remembered her sense of humor. “She had such a wit. She would have been terrible if she hadn’t been so funny. She imitated people, heads of state, after everyone had left a White House dinner. Their accents, the way they talked. She was a cutup. Behind the closed doors, she’d dance a jig.”

Before she left the White House, she placed a plaque in the Lincoln bedroom that said, “In this room lived John Fitzgerald Kennedy with his wife, Jacqueline, during the 2 years, 10 months and 2 days he was President of the United States — Jan. 10, 1961 – Nov. 22, 1963.” Mrs. Richard M. Nixon had the plaque removed after she and her husband moved in in 1969.

To some, Jacqueline Kennedy seemed to fall from grace as her year of mourning ended. She was photographed wearing a miniskirt; she was escorted to lunch and dinner and various social gatherings by prominent bachelors, including Frank Sinatra, Marlon Brando and Mike Nichols; she toured the Seville Fair on horseback in 1966 and, in a crimson jacket and a rakish broad-brimmed black hat, tossed down a glass of sherry. “I know,” she said, “that to visit Sevilla and not ride horseback at the fair is equal to not coming at all.” To some Americans she was no longer just the grieving widow of their martyred President; she was young, attractive and she clearly wanted to live her life with a certain brio.

But Mrs. Kennedy found she also needed more privacy. The more private she became the more curious the public seemed about her conduct. New Yorkers might be considered the most private of all Americans; urban apartment-dwelling grants anonymity to those who seek it. And so she moved to New York in 1964 to an apartment at 1040 Fifth Avenue. It was near the homes of family and friends and also not far from the Convent of the Sacred Heart at 91st Street and Fifth Avenue, where Caroline was to attend school.

New York was not all she had hoped it would be. For one thing, the photographer Ron Galella seemed to be everywhere she went, taking thousands of photographs of her. The preparation and publication of “The Death of a President,” William Manchester’s detailed account of the assassination of President Kennedy, turned into an unexpected battle for Mrs. Kennedy that may have cost her some popularity. Mr. Manchester, whose work was admired by President Kennedy, asked for and received permission from the Kennedy family to do an authorized, definitive work on the assassination. His publisher, Harper & Row, agreed to turn over most of their profits to the Kennedy Library. Mrs. Kennedy, in a rare departure from her usual practice, agreed to be interviewed. Although Mr. Manchester did not stand to profit from the book itself, he did arrange to have it serialized in Look Magazine, starting in the summer of 1966, for which he would be paid $665,000.

Long Fight For Privacy

Mrs. Kennedy became angry. From her perspective, Mr. Manchester was commercially exploiting her husband’s assassination. At one point, she tried to get an injunction in New York State Supreme Court to stop the publication of the book, either by Look or by Harper & Row. The case was settled in 1967, with Mr. Manchester agreeing to pay a large share of his earnings to the Kennedy Library.

Mrs. Onassis never created an oral history, associates said, and her refusal to give interviews has left little for the record that she would have approved. Tapes of two interviews with her — Mr. White’s shortly after the assassination in Dallas and Mr. Manchester’s for his book “Death of a President” — are kept under seal at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library in Boston.

Mr. Manchester’s interview, 313 minutes on tape, was sealed for 100 years and is scheduled to be opened in 2067. The interview by Mr. White is to be unsealed a year after Mrs. Onassis’s death. William Johnson, chief archivist at the library, said he believes the interviews contain material that the authors did not use in their books and might prove useful to historians.

Her silence about her past, especially about the Kennedy years and her marriage to the President, was always something of a mystery. Her family never spoke of it; out of loyalty or trepidation over her wrath, her closest friends shed no light on it and there was nothing authoritative to be learned beyond her inner circle.

The next year, Mr. Onassis and Mrs. Kennedy announced that they would be married. It had been five years since the President’s death. She told a friend, “You don’t know how lonely I’ve been.” The ceremony was held on Oct. 20, 1968. She then became Mistress of Skorpios, the Aegean island that Mr. Onassis owned, and held sway over a palace with more than 70 servants on call. There were four other locations where he had homes. Mr. Davis observed that immediately after her marriage, Mrs. Onassis became more cheerful and outgoing but it was not to last. Within a few years, there were reports that Mr. and Mrs. Onassis were arguing. He was again seen in Paris, dining at Maxim’s with the soprano Maria Callas. Mrs. Onassis was seen in New York in the company of other escorts.

Mr. Onassis issued a public statement that did little to dampen the rumor-mongering. “Jackie is a little bird that needs its freedom as well as its security and she gets them both from me,” he said. “She can do exactly as she pleases — visit international fashion shows and travel and go out with friends to the theater or anyplace. And I, of course, will do exactly as I please. I never question her and she never questions me.”

The marriage continued to founder. Mr. Onassis persuaded the Greek Parliament to pass legislation to prevent her from getting the 25 percent portion of his estate that Greek law reserved for widows. When he died in 1975, his daughter Christina was at his side; Mrs. Onassis was in New York. There was a lawsuit and when it was settled, she received $20 million — far less than the $125 million or more that she might have received.

Mrs. Onassis’ began her career in publishing in 1975, when her friend Thomas Guinzburg, then the president of Viking Press, offered her a job as a consulting editor. But she resigned two years later after Mr. Guinzburg published — without telling her, she said later — a thriller by Jeffrey Archer called “Shall We Tell the President,” which imagined that her brother-in-law, Senator Edward M. Kennedy, was President of the United States and described an assassination plot against him.

In 1978, Mrs. Onassis then took a new job as an associate editor at Doubleday under another old friend, John Sargent, and was installed at first in a small office with no windows. It helped, she said, that Nancy Tuckerman, who had been her social secretary at the White House, already had a job there; the two worked closely for the next 15 years.

At Doubleday, where she was eventually promoted to senior editor, Mrs. Onassis was known as a gracious and unassuming colleague who had to pitch her stories at editorial meetings, just as everyone else did. She avoided the industry’s active social scene, probably because she had so little need to expand her network of contacts. She often ate lunch at her desk, for instance, avoiding the publishing lunchtime crowd at restaurants like the Four Seasons and 44. She worked three days a week — Doubleday never revealed what days they were, for fear the information would attract celebrity-watchers — and took long vacations in Martha’s Vineyard every summer.

But she was very productive, editing 10 to 12 books a year on performing arts and other subjects. Books she published included Bill Moyers’s “Healing and the Mind”; Michael Jackson’s “Moonwalk”; and Edvard Radzinsky’s “The Last Tsar: The Life and Death of Nicholas II.” Her list also testified to her eclectic tastes and to her first-rate contacts. She published a number of children’s books by the singer Carly Simon, a friend and Martha’s Vineyard neighbor. Her love of Egypt inspired her, among other things, to bring the Cairo Trilogy, “Palace Walk,” “Palace of Desire” and “Sugar Street” by Naguib Mahfouz, the Nobel Prize winner from Egypt, to Doubleday, where they were published in translation.

Admiration From Her Writers

In an industry where editors often have little time for their authors, Mrs. Onassis’s spoke admiringly of her curiosity, her interest in their work and her great attention to detail. “Working with her was extraordinary,” said Jonathan Cott, a contributing editor at Rolling Stone who has published several books on Egypt with Mrs. Onassis, the most recent being “Isis and Osiris: Rediscovering the Goddess Myth.”

It seemed daunting to work with an editor who was also a public figure, but Mr. Cott said he was soon put at his ease. In editing sessions at Mrs. Onassis’s home and office, he said, she would make notations on every page of his manuscript, drawing from her own knowledge of Egypt and her extensive collection of Egyptian literature and history books. “She had an incredible sense of literary style and structure,” he said. “She was intelligent and passionate about the material; she was an ideal reader and an ideal editor.”

John Russell, a former art critic for The New York Times and a longtime friend of Mrs. Onassis, remembered her as a shrewd judge of people, but one who was always mindful of their feelings and was careful not to hurt them if her judgments were negative.

“She had an absolutely unfailing antenna for the fake and the fraud in people,” he said. “She never showed it when meeting people, but afterwards she had quite clearly sized people up. She never in public let people know she did not like them. People always went away thinking, ‘She quite liked me, yes, she was impressed by me.’ It was a very endearing quality.”

Mrs. Onassis gave a rare interview to Publishers Weekly, the industry trade magazine, and it was on the subject of publishing. She agreed to the interview, Mrs. Onassis told the reporter, only on the condition that he use no tape recorder, take no photographs and ask no questions about her personal life. In the interview, in typically self-deprecating style, she said she had joined the profession because of a simple love of books. “One of the things I like about publishing is that you don’t promote the editor — you promote the book and the author,” she said.

In the years following Mr. Onassis’s death, she built a 19-room house on 375 acres of ocean-front land on Martha’s Vineyard. She spent considerable time there, as well as in Bernardsville, N.J., where she rented a place and rode horses.

Mrs. Onassis did not marry again. In the last few years, Mr. Tempelsman, a Belgian born industrialist and diamond merchant, had been her frequent companion. The couple, who met about seven years ago, summered together on Martha’s Vineyard and visited her horse farm. She told a friend that she admired his “strength and his success.”

Mrs. Onassis is survived by her daughter, Caroline Kennedy Schlossberg; a son, John F. Kennedy Jr.; her sister, Lee Radziwill Ross, and three grandchildren, Rose Kennedy, Tatiana Celia Kennedy and John Bouvier Kennedy Schlossberg.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard