From a contemporary press report

Leonard F. Chapman Jr., 86, a retired general and former commandant of the Marine Corps who supervised the corps’ withdrawal from the Vietnam War and led it through a period of heightened social and racial tensions, died of cancer January 6, 2000 at Inova Fairfax Hospital, Virginia.

After his military retirement, General Chapman became head of the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service.

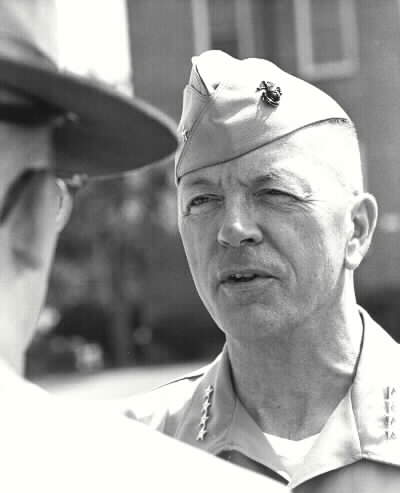

General Chapman, an artillery officer by training, served aboard a Navy cruiser and with Marine landing forces in the Pacific in World War II. He subsequently had several assignments in Washington, where he gained a reputation for cool efficiency. He was assistant commandant of the Marine Corps when President Lyndon B. Johnson passed over two better-known officers who had been touted for the job and appointed him commandant. He took over Jan. 1, 1968.

Within weeks, the communists launched the Tet Offensive across South Vietnam. Marines were heavily engaged in the battle for Hue and in the siege of Khe Sanh near the demilitarized zone between North and South Vietnam.

As disenchantment with the war spread, Marine ground forces began to be withdrawn. Under General Chapman’s direction, the process was completed in 1971. His slogan was, “Don’t leave anything behind worth more than five dollars.”

During the same period, drug and alcohol abuse became serious problems within The Corps, and long-simmering racial tensions broke into the open, mirroring developments in the society at large. There were fights between black and white Marines at enlisted clubs on many bases, and in the summer of 1969 there was a near riot at Camp Lejeune, N.C. In February 1970, someone in a group of blacks threw a hand grenade into a service club in Vietnam. One person was killed and 62 were injured.

General Chapman responded with a combination of discipline and a broad range of programs designed to recognize black cultural symbols, promote understanding between the races and eliminate discrimination in assignments and promotions.

In his widely praised history of the Marine Corps, Allen R. Millett said, “The greatest difficulty proved to be convincing officers and NCOs that they would have to take positive action to stop interracial tension and allay fears of black Marines that they would be victimized by ‘The Man.’ ”

Despite what Millett described as “deep-seated racial hostility in the ranks,” progress was apparent by the time General Chapman retired as commandant December 31, 1971.

“He was a gentleman and a leader,’ ” said General James L. Jones, the current Marine commandant, on General Chapman’s death. “He epitomized everything it means to be called a Marine. He guided our Corps through turbulent times, emobilization and the ultimate recovery from the Vietnam years. His many contributions kept the Marine Corps on the right path and brought us to where we are today.”

General Chapman was a native of Key West, Florida., and graduated from the University of Florida. He entered the Marine Corps through the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps and was commissioned in 1935. One of his early assignments was to attend the Army artillery school at Fort Sill, Oklahoma.

Early in World War II, he commanded the Marine detachment aboard the cruiser Astoria and took part in the Coral Sea and Midway battles, both of which were important U.S. victories. He later served in an artillery regiment in the 1st Marine Division and took part in the bitter fighting for Peleliu and Okinawa.

General Chapman’s later career included command of the Marine Barracks at Eighth and I streets SE and several tours of duty at Marine Corps headquarters.

After the general’s retirement from the service, President Richard M. Nixon appointed him commissioner of the INS, where he served from 1973 to 1976. He lived in Alexandria.

General Chapman’s military decorations included three awards of the Distinguished Service Medal, two awards of the Legion of Merit, one with combat V, and the Bronze Star and Navy Commendation Medal, both with combat V.

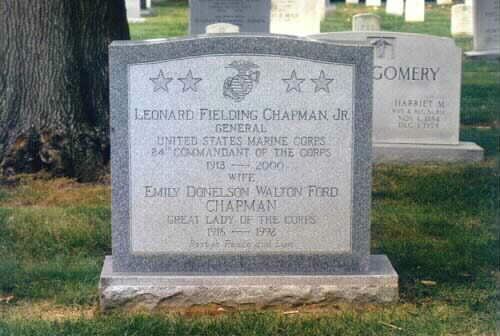

His wife, Emily Chapman, died in 1992. A son, Leonard F. Chapman III, died in 1979. He will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery alongside his wife, Emily, and son Leonard III.

Survivors include a son, Walton Chapman of Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts, and granddaughter.

CHAPMAN, General LEONARD F., JR.

24th Commandant of the U. S. Marine Corps

Of Alexandria, VA, on Thursday, January 6, 2000, at Fairfax Hospital, husband of the late Emily Walton Ford Chapman; father of Walton F. Chapman and the late Maj. Leonard F. Chapman III, USMC; father-in-law of Gayle Chapman Harmes and Carol E. Cone; grandfather of E. Danielle Chapman. Funeral services will be held on Friday, January 14, at 1 p.m. at the Memorial Chapel at Ft. Myer. Interment, Arlington National Cemetery, with full military honors. In lieu of flowers, memorials may be made to the Marine Corps University Foundation, P.O. Box 122, Quantico, VA 22134, Hospice of Northern Virginia or The Salvation Army.

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY (January 14) — More than 700 mourners attended funeral services for former Commandant of the Marine Corps General Leonard F. Chapman Jr. here January 14. General Chapman, who served as the Corps’ 24th Commandant from 1968-71, died January 6, 2000 at the age of 86.

Throughout the memorial service at the Fort Myer chapel, General Chapman was praised for his contribution to today’s Marine Corps by holding the line on Marine Corps standards and values following the Vietnam War.

Commandant of the Marine Corps General James L. Jones described General Chapman as “the Rock of Gibraltar in a sea of change.” He was someone, said the general, who had an “intuitive ability to do the right thing.”

General Jones said General Chapman succeeded because he understood the task of leadership, adding, “this Commandant is very special.”

Former Commandant General Carl E. Mundy Jr., a longtime friend of the Chapman family, delivered the eulogy before an over-flowing chapel . General Mundy characterized him as the “helmsman” whose steadfastness guided the Corps through the tumultuous late ’60s and early ’70s.

At a time when anti-war sentiments ran high, General Mundy said the late Commandant defined the Marine Corps to the public with his observation that “nobody likes to fight, but somebody has to know how.”

He was, General Mundy said, “a gentleman in all respects. He was tough, but he led by logic, character, and an inspiring example. On the day he retired, he was still the sharpest Marine I had ever known.”

Danielle Chapman, the former Commandant’s granddaughter, read a poem she had written on behalf of the family.

Chaplain of the Marine Corps Captain Joseph R. Lamonde, USN, delivered a homily noting the turbulence General Chapman faced during his term as Commandant. “He faced the obstacles of his day head-on and overcame each of them,” Father Lamonde said. “He did the right thing, no matter the public or political opinion. There was no waffling to determine the prevailing political winds.”

General Chapman “provided the strong ground on which to stand” because he was squarely rooted in “valor and values,” Father Lamonde said.

Among those in attendance were several former Marine Corps Commandants and generals, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Jay Johnson, Senators Charles Robb (D-VA) and John Warner, (R-VA) — both former Marines — and Virginia Chaffee, wife of the late Sen. John Chaffee of Rhode Island.

Following the service, General Chapman was taken in a procession nearly a half-mile long to Arlington National Cemetery, where he was buried with full military honors alongside his wife, Emily, and his son, Leonard, III.

General Chapman is survived by his son, Walton Ford Chapman, 56, his granddaughter, Danielle Chapman, and his daughter-in-law, Gayle Chapman Harmes.

Elegy to a Regular Gentleman

By Danielle Chapman

I.

He was a man of marvelous rituals.

He was tall and tanned, like elephant hide,

as he liked to say.

He liked to say so many things:

Good gracious, that’s clever,

Balderdash, dad raddit.

Get in there, to the golf ball.

Studyin on it, to what he was gonna do about it.

Right smart tolerable, to how he felt.

Aah, it’s the nectar of the Gods, when he drank

fresh-squeezed juice from oranges

fresh-picked off the trees in the backyard.

And about a twist of fate:

the wheels of the Gods move slowly,

but they grind exceedingly small.

He died on the same date as his brother

the way his wife died on the same date as their son.

II.

You had large, man’s hands.

Ring and pinky fingernail bit off by a shop class sander.

Fingertips so rough they could chafe a child’s shoulder

and which tapped hard,

when you wanted one of us to pay attention.

Now come on, pay attention.

In the mornings, they did your paperwork at the house on Vassar

In the evenings, they unscrewed the jiggers

and shook them into your regular.

Grandad’s doctor had prescribed bourbon to cure old age ills.

You’ve heard me tell that story before.

It thrilled me

to be privy to the secret ingredients and the necessary joy

of a military man’s everyday drink.

Your regular pronounced with a drawl, like someone’s common name.

But it wasn’t regular at all. It was topaz liquid cat eyes on ice

and you sipped it sitting in your lazy boy, reading the paper.

We shared goldfish crackers from the saucer and watched TV

in a coziness which I thought then was regular

but have learned since

was particular to being in the presence of a great man

who acted ordinary

out of love.

III.

Can you imagine being a child

awakening to meet him on a farmhouse porch

every summer morning?

He sat there clean shaven, fully dressed, bed made

and when I came out at 6 AM, said,

well, good afternoon, let out a sinister chuckle,

heh heh heh

and gave me my morning hug

which was hard and tight and smelled of Aqua Velva.

We studied on what we’d have for breakfast.

The rooster crowed in John Audrey’s field.

The smell of dew rose off the rolling hills.

Sometimes, we spotted a bluebird flit

between the treeline at the cornfield’s edge

and the red, rising sun.

I drank my milk coffee slowly

and hoped that everyone would stay asleep

in their back bedrooms forever

so that I might have more of his morning to myself.

More of his laugh, his whiskers, his slippers, and his workshorts

splattered with white paint.

More listening to the Nashville news from his Heathkit radio.

More discussing matters of international significance.

More appreciation of the English language.

More projects to discuss, which we would accomplish

as a family that day, if he had his way, which didn’t always happen.

We were the the most disorganized body of troops

he had ever seen.

IV.

You are a handsome gentleman in greasy workclothes

standing in the place where my childhood breathes

Clover, chestnut, pinecone, peckerwood, daylily magnolia elms

that have made it through the blight.

The streamlife and the farmlife waft out of the hollows.

A richness from the bramblewoods and mint groves,

the pastures canopied along straight creek.

Cedar from the arcane horde of whittling sticks hidden in the barn.

A breeze by the Baptist church where our ancestors,

black and white, are buried.

The countryside is sweet for you.

It’s called you back by the name of Fielding,

the way your mother did,

Come on home.

Amen.

EULOGY

The son of a Methodist minister, Leonard Chapman came up from his birthplace in Key West, to Deland, Florida, where he grew up. He graduated from the University of Florida, and was commissioned a lieutenant of Marines in 1935, eight days before I was born. Fifty-six years later, he administered the oath that made me the thirtieth Commandant.

Leonard Chapman never outgrew his Southern roots. His Grandfather was a young Confederate soldier from Tennessee who lost a leg in the War. In order to maintain his farm, and to get about comfortably, he trained his horses

to a gait we know as the Tennessee walking horse. General Chapman never abandoned that family homestead, keeping the 1790 tavern on the Natchez Trace – today a National Historic Landmark – as a farmhouse in the hands of a

caretaker. He stayed there a couple of months each year, usually in June and July. A call on the telephone to him would get an answer from Miss Ella, the caretaker’s wife. “Yallow!” she would answer, and after you had identified

yourself as wanting to speak with “The General,” came “Hold on a minute,” followed by the sound of a squeaking screen door, and a loud call: “Fielding; there’s a fellow wants to talk to you on the telephone over here!” Grass roots.

General Chapman’s heroes were Robert E. Lee, and “Lee’s Lieutenants”. He read voraciously, re-reading several times Douglas Southall Freeman’s volumes on the soldier-leaders of the Confederacy. He won the hand of a Southern Belle – Miss Emily Walton Ford, of the Birmingham Fords. Had this grand lady not become a Marine wife, it’s likely she would have claimed the role of Scarlet O’Hara in “Gone With the Wind.” As it was, she brought the elegance and graciousness of the “Old South” into the Corps with her and, eventually, to the Home of the Commandants. Leonard’s love affair with Emily was life-long, and his quiet devotion and attentiveness to her during her prolonged illness before death were an inspiration to all of us who knew them.

He lost his first son, Len — a Marine — to a tragic accident, and became to his daughter-in-law, Gayle, and his grand daughter, Danielle, the companion and father they lost. I’ll never forget, Danny, when you were small enough that you’ll be embarrassed if I talk too much about it, watching your grandfather, in an almost crouched position, teaching you ballroom dancing at an Army – Navy Country Club Friday night dance!

His second son, Walton Ford Chapman, was also a Marine, to his father’s great pride. Working their way through Duke in the early sixties enroute to the Corps, as their Officer Selection Officer, I can recall judging whether the

Chapman boys had been, or were headed home for a visit, by the length of their hair! In more recent years, how excited, and filled with pride your dad’s voice would become when he would announce that he was “…going up to

Massachusetts for a few days to help Walt clear a little timber!”

His pride in each member of his family, his joy in your accomplishments, and his devotion to, and love for you were palpable and inspirational.

I met General Chapman when I was a first lieutenant, and he, a brand new brigadier general. We were in the field at Camp Lejeune, and I recall thinking that this was the sharpest Marine officer I had ever seen. My opinion never

changed. His early years of sea-duty at the outset of World War II left him with a spit and polish that never left. On the day he retired, he was still the sharpest Marine officer I’ve ever known. Others must have had the same opinion, like General Lemuel Shepherd, our 20th Commandant, who ordered him to the Marine Barracks in Washington, where among his lasting legacies is the spit and polish precision and the unexcelled spirit and professionalism he created in the Evening Parades at the Barracks, and the Marine Corps War Memorial.

Leonard Chapman’s manner, his demeanor, and his character matched the perfection of his deportment and appearance. He was a gentleman in all respects. At the outset of his commandancy, a reporter called him “The Quiet Man.” Those closest to him knew him to have been invariably courteous; never to have raised his voice in anger, never to have indulged in gossip, or ever to have bad-mouthed or criticized even those with whom he might disagree. But they knew him also to have an analytic mind that missed no detail, and a layer of tungsten steel determination just below the surface. He was tough, but he led by logic, character, and inspiring example.

In his final tours, as Chief of Staff of the Corps, he helped General Wallace Greene build, train, equip, and employ in combat in Vietnam the largest Marine Corps since World War II. He introduced computers to the Corps, and gave us automated management and information systems. When he became Commandant, the war was on a downward spiral, and the United States wasn’t going to win. Throughout his tenure, his abiding determination was to bring the Corps home in fighting condition, and to preserve it as a spirited American institution.

He faced obstacles in a society where the profession of arms and answering the call to duty were under fire, and in which morals, accountability, and discipline were decaying. He responded by driving the Corps to maintain standards.

When Sister Services succumbed to societal pressures and relaxed standards and discipline, General Chapman tightened them in the Corps. When others advertised, “We want to join you” to prospective recruits, General Chapman

countered with, “Maybe you’re good enough to be one of us!” When anti-war activists railed against war, General Chapman countered with “Nobody likes to fight, but somebody has to know how!” For those in the Corps who weakened under the enormous pressures of the times, General Chapman issued a simple edict: “Marines Don’t Do That” – a leadership thesis used to this day to teach Marines, and leaders of Marines, what is expected of them above and beyond others.

He believed in education. As Commandant, he established the Staff NCO Academy and, in retirement, was founder of the Marine Corps Command and Staff College Foundation, with the purpose of enhancing leadership development among the officers and NCOs of the Corps. He led the Foundation as its President for 14 years, leaving yet another legacy to leadership.

But there was a spirited and fun-loving side to this great man. He was an inveterate golfer, playing the game with skill and enthusiasm to the end. Until recent years, he was a seven handicap. He would tell with a chuckle the story of an officer on whom he wrote a glowing fitness report, but ended it with, “…. but he can’t putt!” He walked the course, carrying his bag, and referred to those in his foursome who chose to ride a cart as “couch potatoes.” Even with his spirited humor, however, the courtly, gentlemanliness was ever there. As he and I played golf together one day, after a particularly humiliating tee shot where, with a mighty swing, I topped the ball and dribbled it into the rough about seventy-five yards out, we walked together in silence for a few moments before he offered, gently, “Carl, that was not among your better shots today!” Classic Chapman.

He loved the Washington Redskins, and rarely missed a game, always, of course, making it first to church on a Sunday. He delighted, when the minister asked the congregation to greet and extend “Peace” to those beside them, in saying instead, “War!” if it were a Redskins Sunday! Noting that his team entered the playoffs last weekend, maybe that was one “for the General!”

Commandants have an occasional habit of gathering their “formers” at some point during their tenures to update on what’s going on. This usually begets spirited discussions of how it used to be, how it might better be, or how it ought to be. General Chapman, usually the elder at such gatherings, as the tempo of suggestions from around the table increased, would delight in breaking in, good-naturedly, but with meaning, to say, “If you junior officers will hold it down, I’ll remind you that each of you had the chance to do what you’re suggesting on your watch. Let’s listen to what the Commandant has to say!”

Linda and I, with Gayle and General Chapman, were guests for dinner at John and Ginny Kinniburg’s home a few years back. As Ginny was busily passing her wonderful dishes, the butter came by. Always concerned for the welfare of “The General,” for whom she and John so devotedly never gave up being aides-de-camp for, and closest friends with, Ginny handed General Chapman the butter with the healthful comment, “I don’t suppose you’ll be having any butter, General, but, please pass it along.” With a wry twinkle in his eye, General Chapman took a sizeable slice for his bread, and quipped, “No, Ginny; I’m going down with the ship!”

Leonard Fielding Chapman, Jr. – husband, father, grandfather, friend, gentleman, Marine – did not go down with the ship. He was the helmsman who steered his life, many of ours, and that of our Corps, through sometimes troubled waters, but with a steadiness that brought calm inspiration, personal strength, and legacy to us, and thousands of others. As we remember him, let us be grateful that America produced one among it’s “few good men and women called Marines,” who we were privileged to know and love. Men of the stature of Leonard Chapman do not often pass this way.

Carl E. Mundy, Jr.

Thirtieth Commandant

From a contemporary press report:

Emily Donelson Walton Ford Chapman, the wife of Leonard F. Chapman, Jr. 76, wife of General Leonard F. Chapman Jr., a retired commandant of the Marine Corps and a former commissioner of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, died of colon cancer November 11, 1992 at the Hospice of Northern Virginia.

A resident of the Washington area off and on since 1946, she lived in Alexandria. While living at the commandant’s residence at the Marine Corps Barracks at Eighth and I streets SW from 1968 to 1972, Mrs. Chapman created a children’s museum on the third floor of the house. She used antiques found there and in her family collections.

By tradition, Marine Corps commandants leave a gift to the house, and the children’s room is to be named in Mrs. Chapman’s honor. Mrs. Chapman was born in Birmingham and reared near Nashville. She attended Vanderbilt University. After marrying Gen Chapman, she accompanied him to Marine Corps posts in Japan, Hawaii and in the United States. She was chairman of Red Cross, Gray Lady and Navy Relief Society chapters at Marine Corps bases where Gen Chapman served. She became a member of the Society of Sponsors after christening the USS Portland, an amphibious ship. She also was a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution and Immanuel Church-On-The-Hill, an Episcopal church in Alexandria. In addition to her husband, of Alexandria, Mrs. Chapman is survived by a son, Walton Ford Chapman of Shelburne Falls, Mass., and a granddaughter. A son, Marine Corps Maj. Leonard F. Chapman III, died in 1979. Section 11, Grave 215.

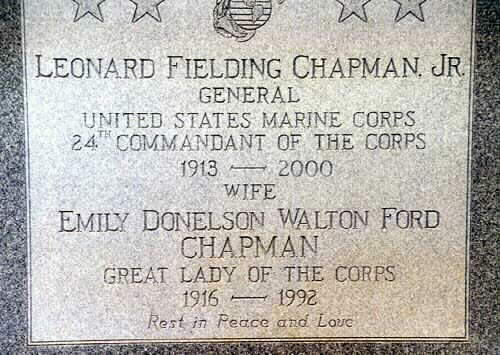

CHAPMAN, LEONARD F

- GEN US MARINE CORPS

- DATE OF BIRTH: 11/03/1913

- DATE OF DEATH: 01/07/2000

- BURIED AT: SECTION 11 SITE 215-1-B

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

CHAPMAN, EMILY FORD

- DATE OF BIRTH: 04/19/1916

- DATE OF DEATH: 11/11/1992

- BURIED AT: SECTION 11 SITE 215-1-B

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY - WIFE OF CHAPMAN, LEONARD F

GEN US MARINE CORPS

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard