Jack Valenti, 1921-2007

A Hollywood Promoter on Both Coasts

By Adam Bernstein

Courtesy of the Washington Post

Friday, April 27, 2007

Jack Valenti, 85, a onetime confidant of President Lyndon B. Johnson who spent nearly four decades as Hollywood’s chief Washington lobbyist and helped devise the “G” to “X” movie-rating system, died yesterday at his home in Washington of complications from a stroke in March.

As president of the Motion Picture Association of America from 1966 to 2004, Valenti represented such powerful studios as Disney, Sony, Warner Bros., Paramount, MGM, 20th Century Fox and Universal as well as several leading independent producers. Earlier, he established political connections as a Texas advertising and public relations executive that led to his strong ties to Johnson.

With an instinctive showman’s flair — notably his grandiloquent speaking style and access to movie stars — Valenti became the dominant power broker connecting Capitol Hill and the film colony. Besides his work on the ratings system in the late 1960s, he helped open up world markets for American-made films and secured passage of copyright legislation to protect movies into the digital age, which led to the proliferation of DVDs.

He also was a major gateway to Hollywood’s financial largesse during the campaign season. On any given week, Valenti met with actors, world leaders and newspaper editors and was regarded as a brilliant and aggressive wielder of his glamorous pulpit.

Harry C. McPherson Jr., also a Johnson intimate who became a Washington lobbyist, called Valenti “an extremely successful advocate of the movie industry. You’d be hard-pressed to find any lobbyist for any industry who did a more successful job than Valenti. I can’t think of many times when Jack Valenti lost.”

“He had a lot to work with,” added McPherson, an occasional lobbying adversary of Valenti’s. “When senator X would want to go to Hollywood and would want some people to attend his fundraiser at the home of [former Walt Disney chief executive] Michael Eisner or some producer or studio chief, he’d talk to Jack. Jack would set it up and very often go out there.”

Lawrence Levinson, a former Washington representative for Paramount, told the New Yorker magazine in 2001: “Jack was able to use the power and glamour and mystique of Hollywood. A new president came in, and [Valenti would] put himself in the center of the process of getting movies to the president. He’d get so excited. He’d call Sid Sheinberg” — the president of MCA/Universal — “and say, ‘Sid! The president is going to Camp David! We’ve got to get him “Jaws”!’ ”

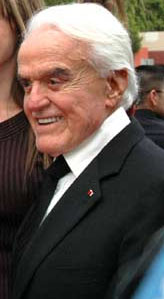

Valenti became known to a wider audience through his appearances on Academy Award telecasts. A diminutive, sprightly man, he was easily identifiable by a well-tanned and protruding forehead covered by snow-white hair. There was also his immaculate executive attire and what one reporter long ago called a “riverboat gambler’s drawl.”

The Texas-born, Harvard-educated lobbyist had a strikingly baroque writing and speaking style heavily influenced by 19th-century British historian Lord Macaulay and British prime minister Winston Churchill. For instance, a movie audience was not composed of ticket buyers but “unknown but enthusiastic companions of a single night.”

He was widely considered an effective promoter for Hollywood on matters including censorship, videotape technology, copyright infringement and, in recent years, video and online piracy of trademarked films.

When Hollywood filmmakers attracted controversy, he routinely defended the studios by citing the freedom of speech guaranteed by the First Amendment as well as the cause of artistic liberty.

This was the case when Valenti, along with MPAA general counsel Louis Nizer, helped create a voluntary rating system in 1968 that changed the way the studios classified a film’s suitability for general audiences. This new arrangement was important, because it kept government intrusion and citizen censors at bay while allowing the artists maximum freedom and the consumer to influence the marketplace by voting with his wallet.

By implementing this voluntary system, the MPAA eliminated a movie code dating from the early 1930s with a long list of onscreen taboos ranging from “excessive and lustful kissing” to showing mixed-race sexual relations. The films had further been subject to city and state censorship boards trying to rid offending material.

The 1968 system — with its long-familiar ratings ranging from “G” for admittance of general audiences to “X” prohibiting those under 17 — was credited with helping keep the U.S. film market competitive with Europe’s. European filmmakers had long ventured into fare laden with adult language, nudity and other forms of explicitness that proved increasingly popular with audiences.

What helped smooth the way for Valenti’s changes was that many of these bolder U.S. films were quality productions with top stars, including “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” (1966), starring Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor. By 1969, “Midnight Cowboy,” starring Dustin Hoffman and Jon Voight, became the only X-rated picture ever to win an Academy Award for best picture.

Valenti had a role in later changes and additions to the voluntary system, including PG-13 and NC-17 ratings. Nevertheless, the ratings system continued to be criticized for how it was applied toward films that accented sex or violence.

One of the strongest critics of the MPAA’s system was Nell Minow, a corporate governance expert who wrote family-oriented movie reviews for Common Sense Media. Citing examples, she told one congressional hearing a few years ago that the MPAA’s system did a poor job of providing families with helpful information.

Minow said recently: “He waited for me to finish, he stood up, learned over, kissed me on the top of my head and said, ‘Nell, that’s why we all need your Web site, because you can give parents what we can’t.’ There was really no way to respond to that. I thought that’s why he’s the most effective lobbyist in Washington.”

The grandson of Sicilian immigrants, Jack Joseph Valenti was born September 5, 1921, in Houston. His father was a clerk in the Harris County Courthouse, where young Valenti often saw office-seekers shaking the hands of well-connected bureaucrats. He began political campaigning at 10 and excelled in high school debate.

At 15, he became an office boy for Houston’s Humble Oil and Refining Co., which later became Exxon Mobil. He returned from World War II a decorated Army Air Forces bomber pilot and a veteran of 51 missions over Europe.

He finished an undergraduate degree in business at the University of Houston in 1946 and received a master’s degree in business administration from Harvard University in 1948.

He returned to Humble and described his most notable work as the “clean bathroom” publicity campaign for the company.

In 1952 he and an old friend, Weldon Weekley, formed an advertising agency. While Weekley oversaw the office work, Valenti lured a series of oil and business executives as clients. He also began handling advertising work for congressional and gubernatorial campaigns and met Johnson, the Senate majority leader, in 1956.

At the time, Valenti had a weekly column in the Houston Post and wrote a deeply flattering account of the future president that described him as “unbending as a mountain crag, tough as a jungle fighter” and called him the “Great Persuader.”

Valenti further cemented their relationship in 1962 by marrying Johnson’s personal secretary, Mary Margaret Wiley. She survives him, along with three children, Courtenay Valenti and John Valenti, both of Los Angeles, and Alexandra Valenti of Austin; a sister; and two grandchildren.

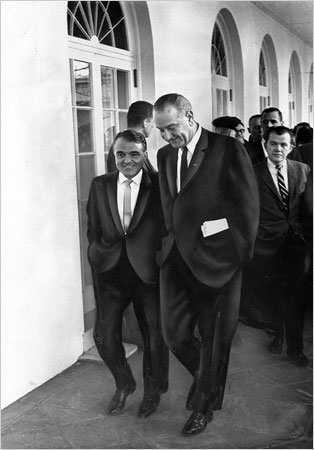

In November 1963, then-Vice President Johnson asked Jack Valenti to handle press relations during President John F. Kennedy’s swing through Texas.

Valenti was in the presidential motorcade in downtown Dallas when Kennedy was fatally shot November 22, 1963 and accompanied the newly sworn-in Johnson back to Washington that night on Air Force One. He appeared in the famous photograph showing Johnson taking the oath of office aboard the plane.

As president, Johnson brought Valenti to Washington in 1963 as his special assistant — a vague position Valenti likened to a “roving linebacker.” He was a presidential troubleshooter, speech editor and trusted deputy for confidential assignments. He was often the first non-family member to greet Johnson in the morning and the last to see him at night.

McPherson, who became Johnson’s special counsel, said Valenti was “enormously valuable as an aide because he could do so much. He could talk to members of Congress, he could take a piece of leaden speechwriting by someone and turn it, maybe not into Churchillian prose, but something that had some zip to it. There was no one he felt too shy to talk to on behalf of Johnson.”

Tom Johnson, a White House fellow during the Johnson administration who later held executive positions at the Los Angeles Times and CNN, said, “Lyndon Johnson had no chief of staff, but Jack was closest to it.”

He said Valenti was “the primary note taker in virtually all of the most confidential meetings LBJ had with heads of state, members of Congress, governors and [National Security Council] meetings.” He also was Johnson’s liaison to the Catholic Church and arranged with utmost secrecy a meeting between the president and Pope Paul VI at the Vatican during a presidential world tour.

Yet Valenti was often described as Johnson’s chief whipping post or “glorified valet,” who loyally absorbed Johnson’s foul-mouthed tantrums and such seemingly humiliating acts as Johnson using Valenti’s lap as a footrest.

Despite such treatment, Valenti continued to describe Johnson in worshipful, often purple prose, as when he told a group of advertising industry leaders in 1965, “I sleep each night a little better, a little more confidently because Lyndon Johnson is my president.”

Afterward, Washington Post political cartoonist Herblock drew Valenti as a slave being whipped into submission. All this brought Valenti the enduring image of a sycophant, political journalist Richard Rovere once wrote.

Valenti’s closeness to Johnson was a top reason Lew Wasserman, president of MCA/Universal Studios and often called the most powerful man in Hollywood, pursued Valenti in 1966 to become MPAA president. Wasserman’s empire had been a frequent target of Justice Department actions, and Valenti proved a valuable contact.

The polished Valenti remained the discreet Wasserman’s frontman in Washington for decades. For his work, Valenti was among the best-paid trade group chief executives in Washington.

On the job, he was tireless yet always appeared impeccably tanned and suave. He logged hundreds of thousands of miles for his causes and at times had to confront foreign cultural ministries that used trade talks to limit or lambaste American film imports. In the early 1990s, he encouraged the MPAA to donate money to European film schools as a way of improving relations.

Videos are now among the top income sources for his client companies, but Valenti was paid for years to denounce what was then new technology. He memorably told a congressional panel in 1982, “I say to you that the VCR is to the American film producer and the American public as the Boston strangler is to the woman home alone.”

In the early 1980s, he successfully lobbied the Federal Communications Commission to prevent the repeal of long-standing financial-syndication rules. His actions allowed the movie industry to keep reaping billions of dollars from reruns. Until the rule was changed in the mid-1990s, television continued to be shut out of owning and syndicating the entertainment programs it aired.

Wasserman had also played an important role, having spoken directly to President Ronald Reagan, whose political rise he helped orchestrate in the 1950s.

When Valenti resigned from the MPAA in 2004, he was reportedly earning $1.35 million, and National Journal magazine ranked him the seventh-highest-paid trade group chief executive in Washington. His MPAA successor was Dan Glickman, a former U.S. congressman and President Bill Clinton’s agriculture secretary.

Valenti contributed opinion pieces to newspapers and magazines such as Reader’s Digest and the Atlantic Monthly. Among his books were “A Very Human President” (1975), about Johnson’s White House years; “Speak Up With Confidence,” a guide to public speaking (1982); and “Protect and Defend” (1992), a Washington-based political novel edited by former first lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. In 2006, he wrote a memoir, “This Time, This Place: My Life in War, the White House and Hollywood.”

Jack Valenti, who became a confidant of President Lyndon B. Johnson and then a Hollywood institution, leading the Motion Picture Association of America and devising a voluntary film-rating system that gave new meaning to letters like G, R and X, died yesterday at his home in Washington. He was 85. The cause was complications of a recent stroke, his family said. He had been hospitalized in Baltimore in March.

For 38 years, Mr. Valenti was the public face of the movie and television production industry and one of its fiercest advocates. He lobbied Congress to protect filmmakers’ intellectual property from piracy and to ease trade barriers overseas. And he fended off lawmakers’ recurring campaigns to curb violence and sex on the screen, arguing for free expression. He devised the film-rating system precisely to avoid censorship by local review boards.

He also remained a starry-eyed fan, cherishing his friendships with Kirk Douglas, Sidney Poitier and Frank Sinatra, falling speechless before Sophia Loren and savoring his seconds in the spotlight as a regular presenter at the Academy Awards.

As a Houston political consultant, he was in the motorcade when President John F. Kennedy was shot on November 22, 1963, and he watched as Johnson was sworn in beside Jacqueline Kennedy aboard Air Force One.

Mr. Valenti soon became known, and for a time mocked, for his unfailing loyalty to Johnson, if not outright idolatry of him. “I sleep each night a little better, a little more confidently because Lyndon Johnson is my president,” he once said in Boston, inviting guffaws nationwide.

Even after leaving a senior post at the White House in 1966, Mr. Valenti remained at Johnson’s service, secretly arranging the president’s surprise detour to the Vatican to meet with Pope Paul VI on the way back from Vietnam in December 1967.

His fidelity was lifelong. Mr. Valenti, a bantam 5-foot-7 who forever looked up to the towering Johnson, picked fights with critical Johnson biographers like Robert Caro and Robert Dallek.

Mr. Valenti’s forthcoming memoir, “This Time, This Place: My Life in War, the White House, and Hollywood” (Crown), does as much to polish Johnson’s legacy as his own. He was to have begun a six-city tour on June 5 to promote the book.

In 1966 Mr. Valenti took his talents for personal politicking — and lionizing his bosses — to Hollywood, heeding the request of Lew Wasserman and Arthur Krim, then chairmen of MCA/Universal and United Artists respectively, that he take over the Motion Picture Association. “If Hollywood is Mount Olympus,” Mr. Valenti once said of his new liege, “Lew Wasserman is Zeus.” He became the organization’s third president.

At the time, Hollywood was still officially operating under the Hays Production Code, the industry’s draconian and increasingly outmoded self-censoring rules that flatly barred nudity, profanity, miscegenation and even childbirth scenes from being depicted on film.

Mr. Valenti was soon confronted with two films in 1966 that convinced him that the code had become obsolete. He dealt with one, “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?,” by negotiating a compromise in which three out of four particular vulgarisms were cut.

Later that year, M.G.M. released Michelangelo Antonioni’s “Blowup” even though that film, showing brief scenes of nudity, lacked Production Code approval. Sensing that other films would also begin flouting the code and in turn create a vacuum into which local politicians and censorship boards might rush, Mr. Valenti decided to act.

“I knew I had to move swiftly, and I did,” he later recalled. “I was determined to free the screen from anything like the Hays Code. But I also emphasized that freedom demanded responsibility.”

So by late 1968 he persuaded the national theater-owners association to buy into a system of voluntary ratings, based on an ascending scale of adult content, that would be enforced at the box office: G, M (later PG), R and X.

The system was not without flaws and detractors, and it required some tinkering. In 1984, after receiving complaints about frightening parts of PG-rated movies (“parental guidance suggested”) like “Gremlins,” the association added the PG-13 category (“parents strongly cautioned”). Though the other ratings were trademarked, the X was not, and pornographers quickly co-opted it. In 1990 the association replaced the X with NC-17 (no one 17 and under admitted), hoping it would be embraced, but distributors have mostly spurned it for commercial reasons, leaving many filmmakers to make wrenching cuts to adult-themed films in pursuit of an R rating.

Mr. Valenti always rebutted critics by citing an annual survey, paid for by the association, showing that parents of young children strongly believed that the ratings were useful.

In 1983, at the height of the Reagan administration’s deregulation efforts, Mr. Valenti led a fight to preserve federal rules intended to protect television producers and studios from the market power of the three major networks. The Federal Communications Commission was considering repealing the rules and allowing the networks to produce programs, thus giving them vertical control over production, distribution and exhibition.

In his memoir, he said he asked Mr. Wasserman, who had once been Ronald Reagan’s agent, and Charlton Heston to urge the president to oppose the repeal. The White House did just that, and the federal rules remained in place until 1995, by which time mergers between studios and networks had rendered them unnecessary.

In Mr. Valenti’s last decade at the association, it became consumed with fighting digital piracy. But one of his bolder strokes, in 2003, blew up in his face. He had learned that half the films being sent to industry people on DVD, known as screeners, for awards campaigns were turning up for sale illegally around the world. So he banned screeners altogether. A storm of protest ensued — loudest of all from the major studios’ own specialty divisions, which rely heavily on awards attention to publicize their films — and the policy was overturned by a federal judge, who said it ran afoul of antitrust laws.

Jack Joseph Valenti was born in Houston on September 5, 1921, to the son and daughter of Italian immigrants from Sicily. He traced his passion for politics to the day his father, a clerk for the city government, took him to a political rally, where the 10-year-old Jack was invited to give his first speech, from a flatbed truck, for the Harris County sheriff. “I never recovered from it,” Mr. Valenti wrote.

As a youth he worked for a chain of second-run movie theaters in downtown Houston, roaming the city putting up posters in storefront windows in exchange for free passes. Hired as an office boy at the Humble Oil Company (an antecedent to ExxonMobil), he attended the University of Houston at night but still managed to be elected class president his sophomore year.

A voracious reader, he devoured everything by Macaulay, Churchill and Gibbon, and his speaking and writing style would mix his native twang with the rhetorical flourishes of his heroes in a brew of cliché, cornpone, compelling phrases and clunkers that one critic called “a kind of Texas baroque.”

In 1982 Mr. Valenti published a guide to oratory, “Speak Up With Confidence,” which was revised and reissued in 2002. He also wrote “The Bitter Taste of Glory,” a book of essays (World, 1971); “A Very Human President” (W. W. Norton, 1975), about Johnson; and a political novel, “Protect and Defend” (Doubleday, 1992), edited by Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

As an Army B-25 pilot in World War II — the Naval air corps had rejected him because of a heart murmur — he flew 51 missions over Italy, but never piloted a plane again after returning his flak-battered bomber to the United States. He went to Harvard Business School on the G.I. bill, then returned to Humble Oil’s advertising department, where he helped its Texas gas stations jump from fifth to first in sales through a “cleanest restrooms” campaign. He co-founded an advertising agency in 1952, with a rival oil company, Conoco, as its first client. He later added Representative Albert Thomas, a Johnson ally, as a client.

It was in 1956 that he met Senator Johnson at a gathering of young Houston Democrats. As a sideline, Mr. Valenti had begun writing a weekly column in The Houston Post, and he rhapsodized there about the senator’s “strength, unbending as a mountain crag, tough as a jungle fighter.” Their friendship grew, and when Johnson became Kennedy’s running mate, he had Mr. Valenti run the ticket’s campaign in Texas. Mr. Valenti helped stage Kennedy’s televised meeting on Sept. 12, 1960, with a group of Protestant Houston ministers, an event that was instrumental in helping him overcome anti-Catholic bias.

Mr. Valenti cemented his ties to Johnson in 1962 when he married Mary Margaret Wiley, a Johnson secretary. The couple accompanied Johnson to Rome for the funeral of Pope John XXIII, and Mr. Valenti was put in charge of the Houston leg of Kennedy’s 1963 swing through Texas. After a dinner there on Nov. 21, Johnson asked Mr. Valenti to fly on Air Force Two the next day. Moments after learning Kennedy was dead, Mr. Valenti was summoned to Air Force One, where he was hired on the spot as a special assistant.

In his memoir he recalled helping rustle up votes for Johnson’s monumental Great Society legislation; witnessing Johnson’s private browbeating of Gov. George Wallace of Alabama after the attacks on civil-rights marchers in Selma; and being accused (unfairly, he maintained) by Robert F. Kennedy of leaking to the news media stories about Kennedy’s chances of being made Johnson’s 1964 running mate.

But Mr. Valenti may have rendered his most vital White House service by being a source of companionship, public praise and private candor, Mr. Dallek said; before leaving the White House, he warned Johnson how much the war was hurting his credibility with voters. Mr. Valenti spent more time socially with the president than any other aide, often bringing along his wife and their toddler daughter, Courtenay Lynda, a Johnson favorite.

In addition to his wife of 45 years and his daughter, now an executive vice president for production at Warner Brothers Pictures, Mr. Valenti is survived by a son, John Lyndon, of Los Angeles, the chief executive of icreate.com, an informational service for the film industry; another daughter, Alexandra Alice, a photographer and video director in Austin, Tex.; and two grandchildren.

Mr. Valenti, who was four days shy of 83 when he stepped down from the motion picture association, continued to come to work, nattily dressed, long afterward. “Retirement to me is a synonym for decay,” he wrote in his memoir. “The idea of just knocking about, playing golf or whatever, is so unattractive to me that I would rather be nibbled to death by ducks. So long as I am doing what I choose to do and love to do, work is not work but total fun.”

1 May 2007:

Jack Valenti’s funeral today at St. Matthew’s Cathedral reflects the mixture of his life, a heady cocktail of politics and show business laced with a shot of the common man and family friends.

Sprinkled among the famous like actor Kirk Douglas, a lector, are family friend and Houston businessman Theodore Dinerstein, also a lector, and Valenti’s long-term drivers Humam Abdul-Malik and Tobar Woolbright, who are among the pallbearers.

Honorary pallbearers number in the dozens and include director Steven Spielberg, News Corp. honcho Peter Chernin, Disney boss Robert Iger and producer Steven Bochco and nearly a quorum call of lawmakers including House Speaker Representative Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif.; Senators Ted Stevens, R-Alaska, Joe Biden, D-Del., and Patrick Leahy, D-Vt.; and Rep. John Dingell, D-Mich., chairman of the House Commerce Committee.

His son John Valenti, Senator Daniel Inouye, D-Hawaii, attorney and family friend Lloyd Hand and Warner Bros. chairman and CEO Barry Meyer will read from Valenti’s soon-to-be-published memoir “This Time. This Place,” while Charles Bartlett, a longtime D.C. neighbor and close family friend, will give the eulogy.

Monsignor James D. Watkins is the homilist and Monsignor W. Ronald Jameson is the rector. The pallbearers are Abdul-Malik; MPAA counsel and executive vp Fritz Attaway, nephews Jack Caltagirone and Vincent Thomas Caltagirone; UMG public policy senior vp Matt Gerson; MPAA external affairs senior vp Rich Taylor; son-in-law Patrick Roberts; MPAA state legislative affairs senior vp Vans Stevenson; and Woolbright.

Valenti, a decorated World War II veteran, will be interred at Arlington National Cemetery in a later ceremony. In lieu of flowers, donations may be sent to the Jack Valenti Macular Degeneration Research Fund at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

Valenti’s burial at least seven years in the making

Former Motion Picture Association of America head Jack Valenti, who passed away last week and had a star-studded funeral on Tuesday, will be buried in Arlington National Cemetery next Wednesday.

But the story behind his burial there goes back to the Clinton administration. On January 18, 2001, just before the first inauguration of President Bush, then-Secretary of Defense Bill Cohen responded to a request from Valenti to be buried at Arlington.

In a letter to Valenti, a copy of which was obtained by Yeas & Nays, Cohen wrote, “I am granting a waiver as an exception to policy that upon your death, you will qualify for an In-Ground Burial at Arlington. Please accept this letter as another token of our appreciation for the many outstanding efforts you have undertaken on behalf of America’s men and women in the Armed Forces.”

Valenti flew 51 combat missions as a B-25 pilot in World War II. Yet burials at Arlington are typically reserved for

career soldiers or those killed in action.

An e-mail sent from Secretary of Defense Robert Gates’ office to several senators and congressmen Tuesday indicated that “Gates has agreed to honor the exception to the internment policy at the Arlington National Cemetery that was approved for Mr. Valenti by [Secretary Cohen].”

Stars and Pols See Jack Valenti Off to ‘Holy-World’

By Amy Argetsinger and Roxanne Roberts

Coutesy of the Washington Post

Wednesday, May 2, 2007

In a funeral Mass that combined the glamour of Hollywood and the power of Washington, Jack Valenti was sent off yesterday to the “great screening room in the sky”– his term for heaven. Yes, the man loved the movies.

More than 1,300 admirers of the legendary motion picture lobbyist and presidential adviser poured into the Cathedral of St. Matthew, including A-listers from both coasts: Directors Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese; actors Kirk Douglas, Michael Douglas, Catherine Zeta-Jones (a knockout in a form-fitting black suit and yellow drop diamond earrings), Robert Wagner and Sandra Bullock; House Speaker Nancy Pelosi; senators Ted Kennedy, John Kerry, Joe Biden, Pat Leahy, Dianne Feinstein and Ted Stevens; plus assorted studio heads and powerbrokers.

Reliable Source columnists Amy Argetsinger and Roxanne Roberts comment about Jack Valenti being sent off in high-style Tuesday with one of the most A-listy funerals D.C.’s ever seen, Zach Braff watching the Wizards’ final playoff defeat, Miss America promising to testify against pedophiles and more.

“He would have loved it,” said Mary Margaret Valenti, his wife of 45 years. “Jack loved parties.”

Valenti’s farewell played out like a red-carpet premiere: Paparazzi snapped shots of VIPs emerging from an endless line of limos; guests greeted each other under the soaring arches of one of Washington’s most beautiful churches; and Valenti’s coffin, draped in ivory, moved slowly up the aisle — followed by his family — to the music of J.S. Bach.

“We look into the life of a man and see a motion picture,” said Monsignor James Watkins, who called Valenti “a great star, a light,” and referred to the great hereafter in his homily as “Holy-world.”

Valenti loved words and speeches — his own and others’ — and so the tributes were florid and heartfelt. Former chief of protocol Lloyd Hand called his friend of 50 years “devoted, loyal, wise and loving.” Journalist Charles Bartlett praised his “Texas touch.” Kirk Douglas said his old pal was the consummate networker, on Earth and probably in the hereafter: “When the time comes for me to be upstairs waiting for Saint Peter to see me, I expect Jack to find me and bring me to the Big Man.”

Valenti completed his upcoming memoirs just before suffering a stroke in March. Publication was postponed because of his illness, but “This Time, This Place” will now be released next month, as originally planned. His son, John, read one of four excerpts during the 90-minute service chronicling Valenti’s Houston boyhood, service in World War II, work for Lyndon Johnson, and four decades as the film industry’s liaison to Washington.

The crowd (more VIPs: Ethel Kennedy, Donald Rumsfeld, Rep. John Dingell, entertainment execs Michael Eisner, Barry Diller and Howard Stringer, Mike and Chris Wallace, Ted Koppel) spilled out onto the steps of the cathedral as the hearse pulled away with sirens and police escort — a little showy, said Mary Margaret, but she added that her husband would have gotten a kick out of it. Then everyone headed to the Ritz-Carlton for a reception and a chance to network.

The consensus was that the diminutive charmer had a unique ability to develop and keep friends — especially the complicated egomaniacs who dominate politics and moviemaking. His life, said Spielberg, was like a Frank Capra script: “When he believed in you, he stood up for you to the point that you’d be looking up at him,” he said. “He never had a disparaging word to say about anybody.”

“If you need a sentence for a speech, you’d call Jack,” Eisner said. “He’d give you four to choose from. Nobody spoke like him.”

“I loved him,” said Wagner simply. “He was always there for me.”

Valenti, a decorated veteran, will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery next Wednesday.

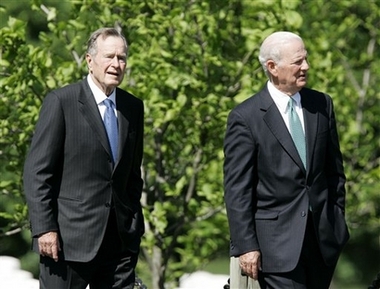

Former President George H. W. Bush, left, and former Secretary of State James Baker arrive

for the burial services for Jack Valenti, Wednesday, May 9, 2007, at Arlington National Cemetery

Former President George H. W. Bush stands in the shade during the burial services for

Jack Valenti, Wednesday, May 9, 2007, at Arlington National Cemetery

Soldiers march next to the horse-drawn caisson carrying the flag draped casket of Jack Valenti

during his burial service, Wednesday, May 9, 2007, at Arlington National Cemetery

Soldiers march next to the horse drawn caisson carrying the flag-draped casket of Jack Valenti during his burial service, Wednesday, May 9, 2007, at Arlington National Cemetery

Soldiers prepare the American flag on the casket of Jack Valenti as his family members cast

a shadow on the roadway, left, during his burial service, Wednesday, May 9, 2007, at Arlington National Cemetery

An Army chaplain, right, presents Mary Margaret Valenti the American flag which draped the

casket of her husband Jack Valenti during his burial services, Wednesday, May 9, 2007, at Arlington National Cemetery

Mary Margaret Valenti, center, holds the American flag which had draped the casket of her

husband Jack Valenti following his burial services, Wednesday, May 9, 2007, at Arlington National Cemetery

Mary Margaret Valenti holds the American flag which draped the casket of her husband

Jack Valenti during his burial services, Wednesday, May 9, 2007, at Arlington National Cemetery

Mary Margaret Valenti, right, receives a hug as she holds the American flag which draped the casket

of her husband Jack Valenti during his burial services, Wednesday, May 9, 2007, at Arlington National Cemetery

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard