U.S. Department of Defense

Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Public Affairs)

News Release

IMMEDIATE RELEASE No. 201-03

April 04, 2003

DOD ANNOUNCES ARMY CASUALTIES

The Department of Defense announced today the identification of the following three soldiers who died as a result of severe injuries on April 3, 2003, in Iraq. They are:

Staff Sergeant Nino D. Livaudais, 23, was assigned to 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment, Fort Benning, Georgia. Livaudais was from Utah.

Specialist Ryan P. Long, 21, was assigned to A Company, 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment, Fort Benning, Georgia. Long was from Seaford, Delaware.

Captain Russell B. Rippetoe, 27, was assigned to A Company, 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment, Fort Benning, Georgia. Rippetoe was from Colorado.

January 26, 2005

Broomfield High School will honor alumni Army Captain Russell B. Rippetoe in a dedication ceremony for the fallen soldier Friday in Eagles Gymnasium.

Rippetoe died April 3, 2003, from wounds sustained at a checkpoint suicide bombing near the Hadithah Dam northwest of Baghdad, Iraq. He was the first soldier killed in Operation Iraqi Freedom to be buried at Arlington National Cemetery. President George W. Bush recalled Rippetoe’s sacrifice in his Memorial Day address to the nation on May 26, 2003.

A flag dedication ceremony honoring 1994 graduate Captain Russell Rippetoe will be at 6:45 p.m. Friday at Broomfield High School’s Eagles Gymnasium, 1 Eagle Way. Rippetoe was killed in Iraq on April 3, 2003. Following the ceremony, the Eagles boys basketball team will play Greeley Central High School. The game starts at 7:30 p.m. Information: (303) 466-7344.

As a recipient of two Bronze Star medals for valor and a Purple Heart, Rippetoe was an inspirational leader to his friends and soldiers alike.

Rippetoe was a multi-sport athlete at Broomfield High School and was involved in many extracurricular activities. He was co-captain of the high school soccer team and elected homecoming king.

“Rippetoe received his commission from University of Colorado-Boulder’s ROTC program and graduated from Metro State University in 1999. He was a natural leader and quickly gained responsibilities in the unit,” Captain Steve Walker, who recruited him, said in a prepared statement.

Rippetoe served in Afghanistan during 2002 and was called to duty in Operation Iraqi Freedom in March 2003.

In April 2003, Rippetoe, Sergeant Nino Livaudais and Specialist Ryan Long were killed by the suicide bombing. Specialist Chad Thibodeau and Specialist Kyle Smith were badly injured.

A heart laid bare

By Clay Latimer

Courtesy of the Rocky Mountain News

April 3, 2004

GAITHERSBURG, Maryland – In the hours before he left for Iraq, Russell Rippetoe found time in the anxious scramble to crowd in some personal business.

Moving through a mental checklist, the Army Ranger called his best friend in Colorado, taped a note to his locker at Fort Benning, Georgia, arranged for a bouquet of flowers to be sent to his mother and phoned his father at their Arvada home three times, though Russell had little to say. When his son called again, Joe Rippetoe, a retired Ranger, Lieutenant Colonel and disabled Vietnam veteran, knew enough to feel uneasy.

“It initially took my breath. I didn’t know what to say. I tried to be strong, but I lost it,” he said. “I couldn’t understand why he had called so many times. I didn’t read between the lines.”

That was the last time Joe Rippetoe spoke to his son.

A year ago today, Russell Rippetoe, Captain of the Broomfield High School soccer team, homecoming king and an Eagle Scout, was manning a nighttime checkpoint near Hadithah Dam in western Iraq when a car approached carrying Iraqi civilians. A pregnant woman got out and ran screaming from the car, Rippetoe stepped toward her, the car exploded, and he and two other soldiers were killed, victims of a terrorist ruse.

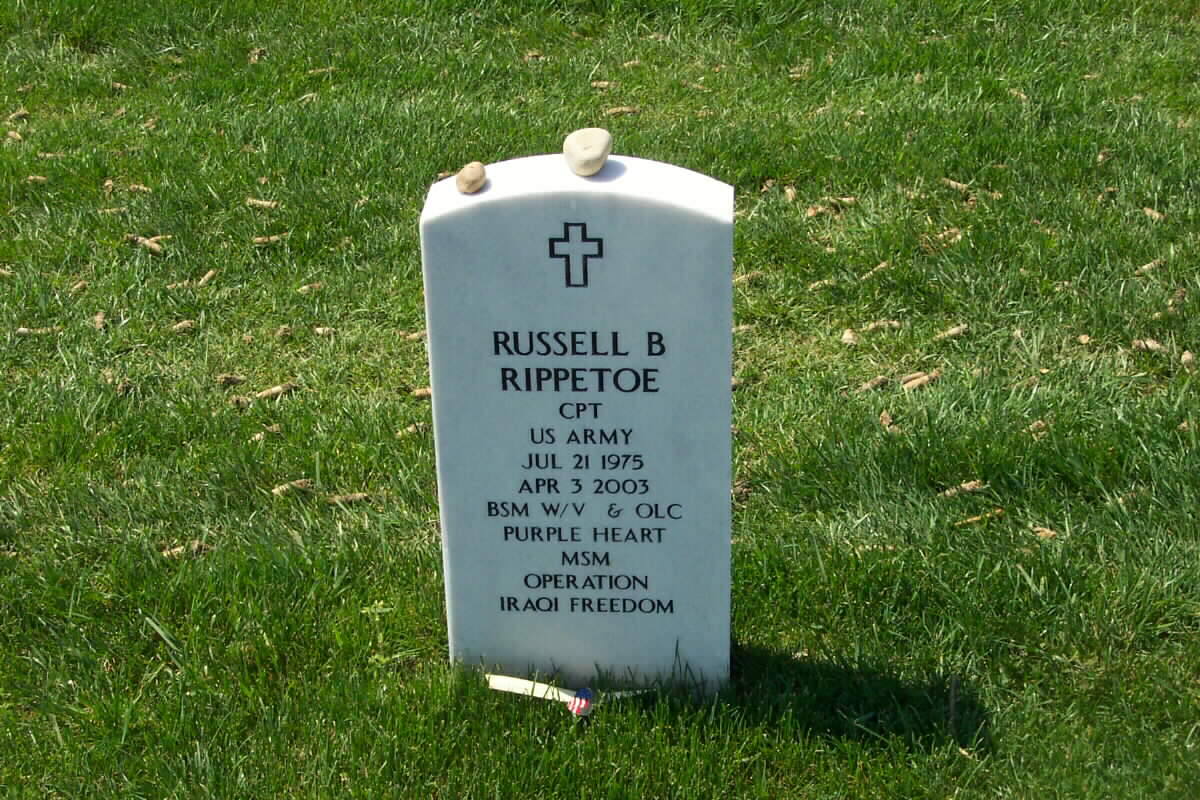

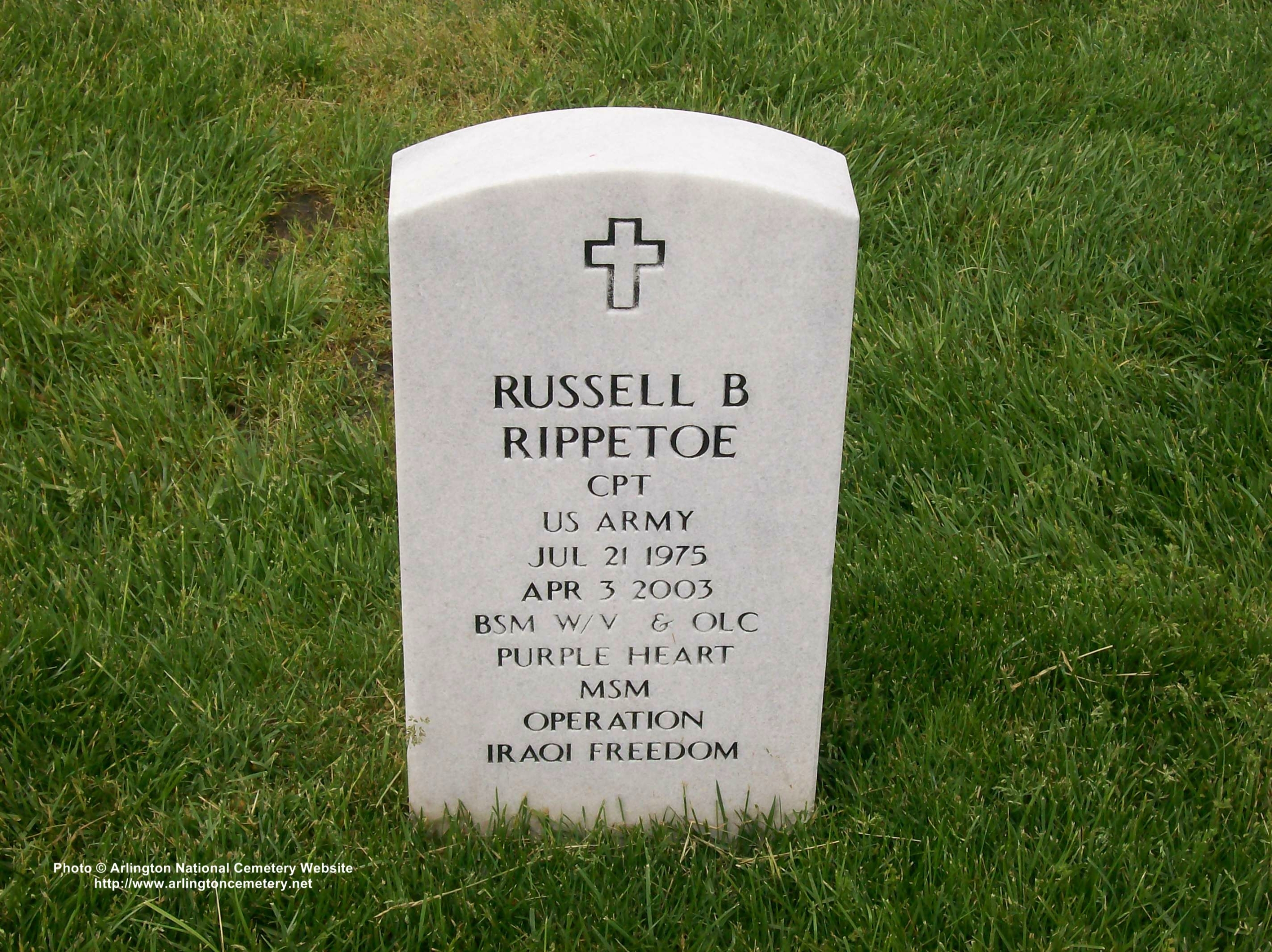

On a gloomy and windy morning a week later, Rippetoe, 27, became the first casualty of the Iraq conflict to be buried at Arlington National Cemetery, the hallowed ground that is a graveyard and memorial to more than 250,000 American fighters stretching to the Revolutionary War.

When honor guard soldiers pulled his son’s flag-covered coffin from the caisson, Joe Rippetoe, using his left hand to guide his right into position, fired off a final salute to his only son.

On Memorial Day, President Bush invited Joe and his wife, Rita, to the White House for breakfast and mentioned Russell in his annual address in the Arlington amphitheater.

Soon the drums and bugles moved on. But not Joe.

Soldier and father

On another overcast and blustery morning at Arlington almost a year later, he struggles to tell his story. He inspects pebbles, pennies and other tokens of remembrance at his son’s tombstone, reads the simple words on a simple marker, walks over to two fresh, muddy graves and comes back to Grave No. 7860, an old soldier conscripted into an ancient nightmare.

“I’ve gone the whole cycle now. I’ve been the soldier, I’ve been the one waiting at home for phone calls and mail and now I’ve buried my son,” he said.

“My son was just a big, lovable teddy bear. He always was the type to look out for people. The way he smiled at you, the way he looked at you – you were his. He had such a big heart. And that’s what killed him.”

For the Rippetoes, military service is a family tradition. Joe’s father was a military man. Joe’s uncles served in World War II and Korea. His nephew was in the thick of Vietnam. According to family lore, a Rippetoe served in George Washington’s army.

When he moved to Gaithersburg in March 2002, Joe Rippetoe, 67, converted an upstairs office into a War Room, where he has gathered old combat maps, old photos (he looks remarkably like his son), combat gear and his and Russell’s medals.

He also has collected Russell’s final possessions: dog tags, a scorched religious emblem, two Bibles, a wallet with about $40 and a diary that chronicles his final days and thoughts, which Joe leafs through periodically.

March 27 – At 18:00 . . . the Shock and Awe air campaign started. I’ve been having chest pains. I think it is from all the excitement; just trying to relax and (know) I work with the best and I know my job. I think we’ve got the planning down now; it is time to do it. I hope my family is not too stressed out . . . Well, it should definitely go down in the history books.

Father eager, too

Joe, too, was eager to get in the game as an ROTC student at Eastern Michigan, where he was a varsity wrestler and student body president in the late 1950s.

“I was always physical, and the military was the most physical,” he said. “When you’re short, you seem to be a little more competitive because you’re at a disadvantage. That’s why I was in very physical sports.”

After graduation, Rippetoe started a 28-year career that included three tours in Europe, three years at the Pentagon as an intelligence director and seven years at the Strategic Air Command in Nebraska, where he helped select bombing sites in the former Soviet Union.

During two tours in Vietnam, Rippetoe led intelligence-gathering missions in enemy-held territory, dropping into booby-trapped hot zones with minimal supplies.

“When you drop into the boonies, you not only have to worry about the bush, you’ve got to worry about trip wires and big, nasty rocks with spikes, which come out of trees,” he said. “You’ve got to worry about limbs with big spikes, or about falling into a pit with big stakes.

“One morning, a replacement jumped in and landed on a mine. We couldn’t find any of him.

“We constantly replaced the point guy because of the pressure. Your heart just pounded. We were in hot water all the time.”

In between foreign assignments, Rippetoe was tooling through Kentucky in his Grand Prix when he spotted two women at a stop sign; one was Rita, a Louisville resident, whom he married in a traditional military ceremony.

“Everybody was in dress uniform,” Rippetoe said. “When I want to feel like I’m on Cloud Nine, I put on my uniform.”

Russell was born in 1975 in Heidelberg, West Germany, three years after his sister, Rebecca, who lives in Aurora with her husband.

“Russell got his fire, and the drive to be the best, to do things right, from his father,” said Brent Tuccio, a longtime friend. “Joe can be a fireball. When Russell got like that, he’d look at me and say, ‘That was a Joe moment.’

“He wanted to be like his mom, wanted to be passive, wanted to be laid-back, wanted to watch things from a distance. He’s half like his dad, half like his mom.”

Worked at making friends

Joe Rippetoe left the military in 1988, suffering from chronic pain and post-traumatic stress syndrome from combat in Vietnam, and moved his family to Broomfield as Russell entered seventh grade.

“Because he didn’t know anybody, he’d shake everybody’s hand when he introduced himself,” Tuccio said. “People kind of gave him a hard time for doing that because it was seventh grade. He was very mature. He wanted to be friends with everybody.”

Rippetoe also joined a church group, forming friendships that lasted until his death, including one with Laura Clark, one of many Colorado friends who attended his funeral.

“I didn’t have a date to my senior prom,” Clark said. “We didn’t go to the same school, and he had a soccer tournament that weekend. But he played soccer all day Saturday, took me to prom and played soccer all day Sunday. He knew how much I wanted to go. He was that kind of guy.”

Rippetoe threw himself into football, karate, wrestling and distance running, but soccer was the ultimate kick. Although he wasn’t a gifted athlete, he transformed himself into a tough, solid sweeper. As captain of the Broomfield High team in his senior year, he broke a leg and collarbone. “He was a grinder,” Tuccio said.

Rippetoe received rave reviews from Broomfield’s water boy – Joe Rippetoe, who dispensed water, gum, towels and encouraging words from his sideline perch in a golf cart.

“I took care of the men,” he said.

Russell Rippetoe entered Metro State in 1994, signed up for Air Force ROTC and moved into an apartment, working a 30-hour week at LoDo restaurants to pay his bills. With model good looks, he earned a spot as an extra in a TV mini-series and was a pinup in the Men of LoDo, an annual calendar promoting lower downtown.

Unable to fly jets because of poor vision, Rippetoe transferred to the University of Colorado’s Army ROTC program as a junior. He left Denver at 5 a.m. for training in Boulder, then returned for a 9 a.m. class at Metro, where he studied criminal justice, hoping to eventually become an FBI agent.

With his father pinning his second lieutenant bars on his uniform, Rippetoe received his Army commission in 1999 in Boulder.

“Joe was so proud, you could see it on his face,” said Jim Mason, a neighbor at the time. “It was very moving.”

Rigid Ranger training

From there, Rippetoe went to Fort Sill (Oklahoma) for Field Artillery Officer Basic Training, and eventually to elite Ranger training, which fewer than 55 percent of applicants complete.

Nine years ago, three Rangers died of exposure after spending eight hours in chest-deep, 52-degree water during jungle training in a Florida swamp. But Rippetoe not only completed the course, he flourished, and in April 2002, he formally joined the 75th Ranger Regiment, the unit portrayed in the movie Black Hawk Down.

As a fire support officer, his job was to call in air strikes on selected ground targets.

Later that year, he left for a three-month tour in Afghanistan, carrying a combat-tailored map his father had prepared.

During lulls in action, Rippetoe played pickup soccer games, wrestled with buddies, laughed and chatted. But the stress became increasingly evident as the weeks passed, especially after Rippetoe, for the first time, saw men die.

Anticipating his return, Rippetoe wrote to his parents: “(I want) to go to New York, Miami or Vegas – somewhere just to let my head clear. I think everything will be the same for me, Mom. You and I have talked about me going somewhere and going back with a different attitude about things. I think about that a lot . . . Dad I still want to sit on the back porch with you and talk about (your) stories and my stories. I know you’ve got a couple of yours hiding.”

When Rippetoe returned to the United States on September 22, 2002, his eyes seemed dulled, a look that his father recognized from Vietnam.

“When a new guy came in, his eyes were bright and glistening, but after about three times in the boonies . . .” he said.

Added Tuccio: “Things were different. He was much more reserved. He still wanted to enjoy things; he really wanted to go out for dinner, loosen up, get that edge off. But I don’t think he did a good job of accomplishing that. That was definitely the first change in him.”

At his sister’s wedding party October 26, Rippetoe saw his family for the final time. For the next six months, the Rangers received restricted and classified training; Rippetoe trained with an Olympic marksman.

“Russell was one of the first people I saw when they got back from Afghanistan,” said Army Spc. Chad Thibodeau, who was wounded in the attack that killed Rippetoe. “They’d probably been on the ground for a half-hour. But he was like, ‘Come over here.’

“So I went over there, and he immediately put me at ease. ‘How is the wife? Is she settled in?’

“His leadership potential was unbelievable. He was charismatic in every way. The first time I met Joe, I knew exactly where Russell got it – the confidence, the general caring about other people. Russell always put himself at the back of the line.”

Assignment: Iraq

By February 2003, there were more than 180,000 U.S. air, land and sea personnel arrayed against Iraq, and the number was growing daily.

Rippetoe anxiously awaited his next assignment.

“He’d called me right before he left for Afghanistan, but for some reason it didn’t hit me hard,” Tuccio said.

“But this was different. He made it clear that this was a horribly worrisome situation. I know (death) crossed his mind; he called me when he filled out his will. He told me, ‘This is for real.’

“But he was ready to go; he knew he had to be.”

As Rippetoe departed for Iraq, he started a combat diary.

March 8 – I got tired of lying to my family. Like everyone else, I let them know we were leaving the country for Iraq the next day. I could hear and feel my mom lose a breath. Mom and Dad both cried. It always sucks to hear your mother cry.

March 9 – It’s like everyone is trying to get into the fight. Everyone is trying to make plans to get into the fight. No one really knows who is going where. Frustrating. Rangers are the only ones willing . . . (and) who’ve been asked to try to jump into Baghdad’s Saddam International Airport. I wasn’t nervous at all before, but the . . . more I learn how (Saddam’s) going to try to stop us . . .

March 16 – It’s been one week, but it feels like it’s been very quick . . . It’s pretty weird (to jump into Baghdad). Who does that? Hope the family is not too stressed out. Watched a show today about POWs in 1990, (the) first Iraq War. That sucks. But they didn’t die. They now all have families so I guess they are good . . . Every day we get intelligence briefings on what we are going to do. Today (Saddam) was putting dirt piles on the runway to obstruct the runway so we couldn’t land. He is making large holes and putting explosives in them, booby-trapping them for jumpers to land on. Nice.

March 21 – We just got the call from the CO that in three days we’re going to jump into Baghdad International Airport . . . It looks like it’s getting close to showtime. Hope all the air-defense artillery is gone.

March 23 – (The airport plan is abandoned). I wanted to jump to see if I would hold up to the stress and do my job to the standard of all the Rangers.

March 25 – Watched some chick surfer movie. It passed the time.

March 27 – (As the Shock and Awe campaign began) Think about what Mom and I talked about: All things happening for a reason, and God knows the reason.

April 2 – On 28th of March I did my first jump into (airfield) in Western Iraq. No resistance. But about 10 got hurt. We secured about 25 buildings, two detainees.

On March 29, Joe and Rita pulled up to their new home in Maryland, where Rita was starting a new job at the Department of Justice. Propped on the doorstep was a vase of flowers. “Mom, don’t worry, we’ll see you soon,” an attached card read.

Checkpoint tragedy

On the night of April 3 in Iraq, Rippetoe and his men were inspecting cars as they lined up at a checkpoint more than 7,000 miles from their American homes.

A woman jumped out of a car while screaming, “I’m hungry, I need food and water.”

When Rippetoe, Staff Sergeant -Nino D. Livaudais, 23, of Utah, and Specialist Ryan P. Long, 21, of Seaford, Delaware, ran up to her, the car exploded, killing all three Rangers. The woman and the driver of the car also were killed.

“I remember the vehicle actually exploding,” Thibodeau said. “I woke up a minute or two later, I’m guessing. Then I was completely conscious of everything. It was very, very clear in my mind exactly what had happened. Nobody had to tell me: It was a suicide bombing or car bombing.”

Doctors worked furiously on the victims at a nearby collection point before loading them on a chopper.

“I could hear them working on Russell; he was on my left side,” Thibodeau said. “They were talking among themselves as they loaded the bird. I heard them say, ‘We’ve got two injured and three KIA (killed in action). Nobody had to tell me what had happened to Russell.”

Hearing a pre-dawn knock on their door, Joe and Rita climbed from bed, headed down a hall, descended a flight of stairs, and as they hit the final step, saw three Rangers through a window. The Rippetoes collapsed into each other’s arms.

“You don’t have to say anything; I’ve done what you’re doing,” Joe told the soldiers.

A military funeral

More than 100 of Rippetoe’s family and friends attended the funeral, and eight Rangers from his unit were honorary pallbearers. Next to the grave were framed pictures of Rippetoe as a smiling baby, as a soldier in fatigues smiling and holding a rifle and as a son kissing his mother on the cheek.

Thibodeau left his bed at Walter Reed Army Medical Center to attend the funeral. Joe Rippetoe insisted he ride from a meeting area to the gravesite in his limousine.

“When I got in, I think the first thing his mom said was, ‘We don’t have a son anymore, at least not one we can talk to every day, so I expect a few phone calls from you. You have one mom, and you’re married so you probably kind of have a second mom, so now you have a third mom – and another father and sister,’ ” Thibodeau said.

“They’re a remarkable family. Russell is still an inspiration for me. I’m pretty much a lifer now. Maybe someday I’ll be able to complete some of the things Russell started, some of the things Russell won’t have a chance to do.”

After the ceremony, the Rippetoes received the flag that draped the coffin. A few days later, Joe discovered shell casings from the 21-gun salute in the folds of the flag.

In retrospect, Joe had sensed his son’s uneasiness as he departed for Iraq, a feeling that was driven home when he traveled to Fort Benning to collect Russell’s belongings. His clothes and other possessions were neatly aligned on a bed, which was highly unusual. And his final note – the one attached to his locker – explained what he wanted if he died.

“I want a military funeral, and I want it to be my people,” it read.

Russell Rippetoe had a premonition he would die.

“It was creepy,” his father said last Memorial Day.

But Joe had been apprehensive as well; in fact, he had prepared a combat booklet for Russell, warning him to remain vigilant at all times. In the end, though, Russell led with his heart.

“He wanted to help that woman,” he said.

As the first anniversary of his son’s death neared, Rippetoe remained a dedicated soldier, helping other soldiers and their families. When he learned a Ranger would be buried in Erie, Pennsylvania, the next day, Rippetoe hopped in his car and made it to the funeral in time. “If there’s a funeral on the East Coast, I’m there,” he said.

He works closely with a man in Texas who produces the “Shield of Strength,” a 1-by-2-inch emblem that hung on the chain around Rippetoe’s neck when he was killed. The shield displays a U.S. flag on one side, and a quote from Joshua 1:9 on the other: “I will be strong and courageous. I will not be terrified, or discouraged, for the Lord my God is with me wherever I go.”

But Joe Rippetoe also broods – about his life, his son’s life and missed opportunities.

“We had a good relationship, but there are still many, many things I would have liked to have done,” he said. “Instead of saying, ‘Son, how’s the oil in your cars,’ instead of worrying about all the knickknack things, it should have been, ‘Hey, Hon, let’s go to a football game, let’s do this, let’s do that.’ I was too rigid, too serious.

“I wanted so much to be the best parent. But everything took a back seat to my work. My priorities were all screwed up. I talked the talk, but I didn’t walk the walk. Anyone can be a father; it takes a lot to be a dad.

“I can’t see Russell now; I can’t touch him now,” he added, standing at his son’s grave. “But I can talk to him. I was blessed to have him as my son. When my wife dies and I die, we’ll be interred here, next to him.”

Army Captain Russell B. Rippetoe

March 19, 2004

• Hometown: Arvada

• Unit: 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment

• Died: April 3, 2003, from injuries caused by a car bomb at a checkpoint in northwestern Iraq.

• Age: 27

To those who knew the energetic, good-hearted and above all physical force that was Russell B. Rippetoe, it still doesn’t seem possible that he lies buried in grave No. 7860, Section 60 of Arlington National Cemetery, the first casualty of the war in Iraq to be laid in that hallowed ground.

Two of Rippetoe’s men were killed with him, but two survived, in part because Rippetoe ordered them to stay back as he approached the car bombers’ vehicle. That kind of caution was typical because “Russell loved his men,” said his father, retired Lieutenant Colonel Joe Rippetoe.

The younger Rippetoe’s tendency to sacrifice himself for the team was a constant. As captain of the Broomfield High School soccer team, he broke a leg and his collarbone, his father said. As homecoming king, Russell refused to let the collarbone keep him from the big dance. He attended graduation on crutches because of the broken femur.

Rippetoe approached the Army with the same zeal as he did soccer, football, karate, wrestling or distance running. Not content just to be in the Army, he became a Ranger, “the cream of the crop,” his father said. Rippetoe won numerous commendations, including a Purple Heart and two Bronze Stars. He intended to join the FBI or Secret Service after the Army.

Always, said his father, “a friend of those who weren’t popular,” Rippetoe inspired fierce loyalty in his men. On the day of his funeral, one of the men injured in the bomb blast insisted on leaving his hospital bed, despite having surgery scheduled that day, and attended the service in a wheelchair.

When the wheelchair became mired in the Arlington mud, Specialist Chad Thibodeau lifted himself from the chair and limped to his commanding officer’s grave site.

It was something Rippetoe would have understood.

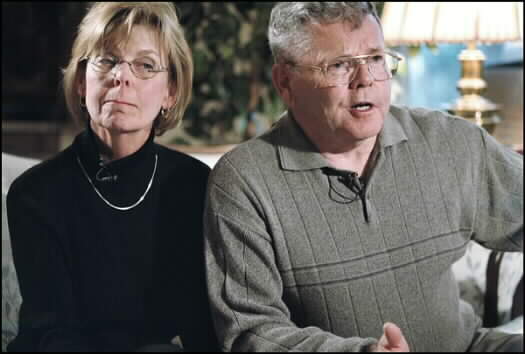

The family of U.S. Army Captain Russell Rippetoe; (L-R) his father

Army Lieutenant Colonel Joe Rippetoe (retired), his mother Reta and his sister Rebecca

Kim all watch a remembrance ceremony honoring the special operations casualties

at Arlington National Cemetery, April 16, 2003.

From President George W. Bush’s Memorial Day Address to the Nation

Arlington National Cemetery, 26 May 2003:

Almost seven weeks ago, an Army Ranger, Captain Russell Rippetoe was laid to rest in Section 60. Captian Rippetoe’s father, Joe, a retired Lieutenant Colonel, gave a farewell salute at the grave of his only son. Russell Rippetoe served with distinction in Operation Iraqi Freedom, earning both the Bronze Star and the Purple Heart.

On the back of his dog tag were engraved these words, from the book of Joshua, “Have not I commanded thee? Be strong and of good courage. Be not afraid, neither be thou dismayed, for the Lord thy God is with thee.” This faithful Army captain has joined a noble company of service and sacrifice gathered row by row. These men and women were strong and courageous and not dismayed. And we pray they have found their peace in the arms of God.

Nation Buries War Dead at Arlington: 11 April 2003

By EILEEN PUTMAN,

Associated Press Writer

ARLINGTON, Va. – “Taps” is played here two dozen times a day, the notes as haunting and lonely as death, this hallowed ground’s abiding presence.

In Arlington National Cemetery, where the nation buries many of its war dead, horse-drawn caissons bear flag-draped coffins across a sea of white, military-issue tombstones. Buried here are those who served in Vietnam, Korea, the two World Wars, the Civil War, the American Revolution.

Young warriors barely past voting age and old retired vets lie next to each other, grave locations dictated more by logistics than military accomplishment.

“There is no rank structure in death,” says cemetery spokesman Tom Findtner, a line that sounds well-used.

More than 285,000 people are interred in the cemetery’s 624 acres, and 25 to 27 are added each day as the World War II veterans move through their 80s. Also buried here are former presidents, slaves, astronauts and members of Congress. During the height of the Vietnam War, as many as 40 funerals took place daily.

Funerals occur on weekdays, but after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks they were conducted into the evening and on Saturdays to accommodate victims from the plane crash into the nearby Pentagon.

If U.S. casualties in Iraq — 105 as of Friday — produce a large number of dead, the cemetery would again expand hours, said spokeswoman Barbara Owens.

Burial space is tight, and the cemetery plans to add 43 acres from adjacent military property. Lack of space has brought restrictions on who is eligible for in-ground burials. Relatives are interred in the same plot as their military personnel, where possible, and the cemetery encourages use of the columbarium, a facility for cremated remains.

Some of the dead, like Captain Russell B. Rippetoe, 27, an Army Ranger killed last week when a car bomb exploded at an Iraqi checkpoint, died in military action and came home to the honors accorded a war hero. He was the first U.S. military casualty buried here from the Iraq war.

As befits a place that has been burying heroes since 1864 — pre-Civil War dead were moved here after 1900 — the rituals are many and precise. One, the changing of the guard at the Tomb of the Unknowns, is a major attraction for the 4.5 million tourists who stream through cemetery gates each year.

It was President Kennedy’s televised funeral that gave many Americans their first sight of the horse-drawn caisson, an open-air carriage that carried Kennedy’s coffin here from Washington, just across the Potomac River.

On Thursday, the caisson carrying Rippetoe’s casket was pulled by a team of six matched grays and escorted by a seventh ridden horse as a military band played “Battle Hymn of the Republic” and later, “America the Beautiful.”

Seven soldiers fired rifle volleys — the number of shots depends on the deceased’s rank. Then came “Taps” — played for all funerals — as a lone bugler stepped apart from the band and blew his solitary notes.

Rippetoe’s father, a retired Army officer disabled during Vietnam combat, sat in uniform with his wife Rita as the Army presented them with their son’s posthumous medals, among them the Bronze Star for valor.

The U.S. flag from their son’s casket was folded with military precision. A member of Rippetoe’s unit — 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment — presented it to Rippetoe’s father and knelt to recite, in a choked voice, the traditional words intended as solace for those left behind:

“On behalf of the president of the United States and a grateful nation, I present you with this flag as a token of the honor and faithful service of your loved one.”

Joe Rippetoe returned the salutes of his son’s fellow Rangers.

The family received a formal condolence card from a member of the Arlington Ladies, a women’s group that sends someone to every funeral. That tradition began in 1972 after an Army General happened on a burial with no mourners.

Even as Rippetoe’s funeral was ending, another was beginning. On a road nearby was parked a yellow backhoe, its driver waiting for the mourners to leave so the more practical tasks of burying the dead could go forward.

Rippetoe’s grave — No. 7860, Section 60 — is in an area where reminders of war’s cost in young lives are inescapable. Behind his is a grave with the remains of two soldiers killed when their helicopter was downed in Southeast Asia in 1971.

Next to Rippetoe lie Sergeant Joshua M. Harapko, 23, and Private First Class Shawn A. Mayerscik, 22, killed in a March 11 helicopter crash at Ft. Drum, N.Y. Their graves, like his, are too new to have received the tab-shaped white marble markers that are standard issue here.

Funerals are scheduled next week for more Iraq casualties, among them Marine Second Lieutenant Frederick E. Pokorney Jr., 31, who died March 30 in an ambush near Nasiriyah. Like Rippetoe, who coordinated artillery from the ground, Pokorney had a dangerous field artillery job.

Pokorney’s uncle, Richard Schulgen, said in an interview his nephew had wanted the honor of being buried at Arlington, where a grandfather and great uncle are also laid to rest. An enlisted man, Pokorney had recently become a commissioned officer and was proud of his service to his country.

“He was proud of what he was doing and proud of his family, a hardworking guy — the best guy you can ever know,” said Schulgen. “I hope the American people don’t forget.”

Here, they don’t.

Fallen Soldier Honored in Arlington

He’s the First Combat Death in the War to Be Buried at National Cemetery

By Annie Gowen

Courtesy of The Washington Post

Thursday, April 10, 2003

Among the mourners, retired Army Lieutenant Colonel Joe Rippetoe stood flexing and unflexing his right arm, stiffened from the biting cold and the wear-and-tear of 28 years in the military.

When honor guard soldiers pulled his son’s flag-covered coffin from the caisson, Rippetoe was ready. He slowly bent his right arm in a final salute to his only son, the 27-year-old Army captain who died with two other U.S. soldiers in a car bomb attack in Iraq on April 3, 2003.

Today, Captain Russell B. Rippetoe became the first combat casualty from the Iraq war to be buried at Arlington National Cemetery, according to cemetery officials.

As a bitter wind spun cherry blossoms from the trees, a black caisson drawn by six gray Shire horses bore the young soldier’s coffin to the grave. The U.S. Army Band marched through the mud to a stirring “Battle Hymn of the Republic.” Soldiers from the U.S. Army’s 3rd Infantry Regiment “Old Guard” honor guard from nearby Fort Myer fired three ceremonial rifle shots as a tribute.

“For 27 years I was blessed with a person that had a big, big heart,” Rippetoe said after the ceremony. “I can’t reach out and touch him, but I can talk to him and I see him . . . the little indentations on the side of his mouth when he smiles? It melts your heart.”

In his brief eulogy, Army Chaplain James May remembered Rippetoe as a gifted leader who embraced his Army career in the elite 75th Ranger Regiment with zeal.

“All the things he did were done to the fullest,” May said. “Russell was a man who loved his troops. And they loved him.”

Rippetoe was raised in Arvada, Colorado, a suburb of Denver, but his parents had just moved to Gaithersburg, Maryland, March 28 so Rita Rippetoe could take a new position at the Justice Department.

The first thing they saw when they walked up the sidewalk to their new home was a bouquet of lilies sent by their son. He signed the card “Relax Ma, I’ll see you soon.” They’d barely unloaded their moving boxes when they learned of his death.

Rippetoe said his son was also a spiritual person — a “man of faith” as May put it — who took a Bible with him when he was deployed to Iraq. Today, May read from the scripture Rippetoe had engraved on the back of his dog tags from the Book of Joshua.

“Have not I commanded thee? Be strong and of a good courage; be not afraid, neither be thou dismayed: for the Lord thy God is with thee . . . “

Rippetoe became interested in joining the Army when he was a criminal justice major at Metropolitan State College of Denver in the late 1990s, friends said. He was also inspired by his father, now 66, who is a retired Army lieutenant colonel, also trained as a Ranger, and did two combat tours in Vietnam.

In 1999, Rippetoe earned his Army commission and was later assigned to Company A, 3rd Battalion 75th Ranger Regiment in Fort Benning, Georgia. He served in Afghanistan from October, 2001 to January, 2002 before he was deployed to Iraq.

“He loved being a Ranger,” said Captain Logan Stanton, a friend who trained with Rippetoe and was at the funeral. Rippetoe was a fire support officer, he said, which meant that he was with the infantry and called in air strikes during battle. “It was a very big job,” Stanton said.

On April 3, Rippetoe was manning a coalition checkpoint near Hadithah Dam in Northwestern Iraq when a car approached carrying Iraqi civilians. A pregnant woman got out and ran screaming from the car. Then, in an explosion Rippetoe and two others from his regiment were killed.

“The woman was saying ‘I’m hungry, I need food and water’ and Rusty walked over to take charge and he was caught in the blast,” Rippetoe said. Army Specialist Chad Thibodeau who was wounded in the attack left his bed at Walter Reed Army Medical Center for the day to attend the funeral.

“He was a good friend of mine. We’ll all miss him,” Thibodeau said after the service. He did not want to discuss the attack.

As the service drew to a close, a dozen members of the elite Rangers, wearing their trademark khaki berets and “dress green” uniforms, filed past the casket and a framed collage of pictures of their comrade. There was a black-and-white photo of Russell as a baby as well as a snapshot of the solid young man he became, wearing fatigues and looking fiercely into the camera.

The Army Rangers presented the young man’s posthumously-awarded combat medals to his stricken parents — two Bronze Stars for valor, a Purple Heart and a meritorious service medal, as well as the flag from the coffin.

Rippetoe and his wife invited all the mourners to their new home in the Montgomery Village section of Gaithersburg after the funeral. He said that his new neighbors have been wonderful to them — bringing plates of food and offering to help unpack.

“When they heard about Rusty, the flags went up,” he said.

But some gifts are not yet welcome. The Army wants to return Rippetoe’s dogtags, the ones with Scripture engraved on the back. Rippetoe said they should wait.

“I told ’em my wife and I aren’t ready to receive those yet,” he said.

Sereant First Class James MacKenzie plays ‘Taps’ during the funeral of Army Ranger Captain Russell B. Rippetoe at Arlington National Cemetery Thursday, April 10, 2003. Rippetoe, 27, an Army Ranger from Arvada, Colorado, and two other soldiers were killed April 4 when a car bomb exploded at an Iraqi checkpoint. Rippetoe was the first soldier from the Iraqi conflict to be laid to rest at Arlinton National Cemetery.

Retired Lieutenant Colonel Joe Rippetoe, right, father of Army Ranger Captain Russell B. Rippetoe, is overcome with emotion during

the funeral of his son at Arlington National Cemetery Thursday, April 10, 2003. Rippetoe, 27, an Army Ranger from Arvada, Colorado, and two other soldiers

were killed April 4 when a car bomb exploded at an Iraqi checkpoint.At left is Rippetoe’s mother Rita.

Army Ranger Captain Shawn Daniel, left, presents the flag to Rita, the mother of Army Ranger Captain Russell B. Rippetoe,

as his father, retired Lieutenant Colonel Joe Rippetoe looks on at Arlington National Cemetery Thursday, April 10, 2003.

Saluted as ”a warrior and a Ranger,” Capt. Russell B. Rippetoe was laid to rest Thursday, 10 April 2003, at Arlington National Cemetery, the first soldier from the Iraqi conflict to be buried on the historic grounds.

Rippetoe, 27, an Army Ranger from Arvada, Colorado, and two other soldiers were killed last week when a car bomb exploded at a checkpoint.

Specialist Chad Thibodeau, who was wounded in the blast, was bandaged and watched the service from a wheelchair. Another Ranger, injured in a separate incident in Iraq, was on crutches with a heavy knee brace.

Eight Rangers from Rippetoe’s unit, wearing khaki berets and blinking back tears, were honorary pallbearers.

Lieutenant Colonel James May, the Army chaplain, called Rippetoe ”a man of faith” who had engraved a Bible passage from Joshua on the back of his dog tags: ”Have not I commanded thee? Be strong and of a good courage; be not afraid, neither be thou dismayed, for the Lord thy God is with thee whithersoever thou goest.”

”When he joined, he joined full force. … He didn’t just join the Army, he joined the Rangers,” said May. ”Russell was a man who loved his troops and they loved him.”

Beside the grave, inside a wreath of flowers, were framed pictures of Rippetoe, as a grinning infant, as a young soldier in fatigues smiling in a tent and holding a rifle, and as a son kissing his mother, Rita, on the cheek.

A team of gray horses pulled a black caisson that carried Rippetoe’s silver casket to the gravesite. The family followed.

Three sharp cracks of gunfire rang out from a seven-member rifle party and a bugler, standing among rows of white headstones on the cold, damp morning, played ”Taps.”

Rippetoe’s father and mother were given the Bronze Star Medal for Valor and the Purple Heart that their son was posthumously awarded, and Captain Shawn Daniel, a friend of Rippetoe’s, presented them with the flag that had been draped over the coffin.

Rippetoe’s father, retired Lieutenant Colonel Joe Rippetoe, who was wounded in Vietnam, returned each salute from the Rangers who knelt or stooped in front of the parents expressing condolences.

The younger Rippetoe was a fire support officer, who called in airstrikes and artillery support for his unit, said Capt. Logan Stanton, who was based with Rippetoe at Fort Benning, Georgia.

”He loved being in the Rangers,” Stanton said. ”He was a warrior and a Ranger.”

Rippetoe was manning a checkpoint in Iraq when a pregnant woman jumped from a car screaming in fear. The soldiers approached the car and it exploded, killing Rippetoe, two other soldiers, the woman and the driver, according to the Defense Department.

The Pentagon said Thursday that 105 U.S. servicemembers have died since the war began.

Captain Russel Rippetoe

Captain Russel Rippetoe, 27, was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery at 8:30 a.m. He was killed April 3 with two other soldiers during a suicide bombing at a Special Operations checkpoint in western Iraq.

Rippetoe grew up and lived in Arvada before his assignment took him to Fort Benning, Georgia.

He’s the first soldier from the Iraq war to be laid to rest at the historic burial ground just outside Washington.

His flag-draped coffin was brought to the site by a horse-drawn carriage. Eight Army Rangers from his unit blinked back tears as they acted as honorary pallbearers.

Three sharp cracks of gunfire rang out from a seven-member rifle party and a bugler, standing among rows of white headstones on the cold, damp morning, played “Taps.”

His parents were presented with a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart that their 27-year-old son was awarded posthumously.

Lieutenant Colonel James May, the Army chaplain, called Rippetoe “a man of faith” who had engraved a Bible passage from Joshua on the back of his dog tags: “Have not I commanded thee? Be strong and of a good courage; be not afraid, neither be thou dismayed, for the Lord thy God is with thee whithersoever thou goest.”

His family said they plan to hold a memorial service in Arvada at a later date.

Army To Bury Fallen Soldier At Arlington

Suicide Bomber Kills Rippetoe

April 10, 2003

Funeral services will be held this morning at Arlington National Cemetery for an American soldier who died in the war with Iraq.

Army Captain Russell Rippetoe was killed in western Iraq on Friday when a car exploded at a checkpoint he was manning.

The 27-year-old soldier lived in Colorado, but his parents moved to Gaithersburg, Maryland, last month. The funeral service will begin at 10 a.m.

Rippetoe was an Army Ranger just as his father was before him. Friends said he wanted to follow in his father’s footsteps. According to the Denver Post, he joined the ROTC at the University of Colorado at Boulder while he attended Metro State College in Denver.

Rippetoe’s awards and decorations include two Army Commendation Medals, the National Defense Service Medal, the Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal, the Army Service Ribbon, the Ranger Tab and the Parachutist Badge.

He was posthumously awarded the Bronze Star Medal for Valor and the Purple Heart.

He was deployed to Afghanistan as part of Operation Enduring Freedom from October 2001 to January 2002.

After his death, his family issued a statement that read, “Russell loved this nation and America has lost a true American hero. We are very proud of him and his service to our country. His sacrifice was made doing exactly what he wanted to do.”

Two other soldiers, Staff Sergeant Nino D. Livaudais, 23, of Utah and Specialist Ryan P. Long, 21, of Seaford, Delaware died as well, and two more people were injured.

Pride, Sorrow Mingle In Maryland

Couple’s Loss

Son, an Army Captain, Died in Suicide Attack

Courtesy of The Washington Post

By Michael H. Cottman

Tuesday, April 8, 2003

Joe and Rita Rippetoe sat inside their new home in Gaithersburg yesterday, the boxes from Colorado still stacked around them, unopened. This was going to be the next exciting chapter for the couple. Rita had just received a promotion at the Justice Department, where she works as an administrator.

But instead of hanging pictures and meeting neighbors, they are making funeral arrangements for their son.

U.S. Army Captain Russell B. Rippetoe, 27, was killed April 3, 2003, in a suicide car bombing at a checkpoint 130 miles northwest of Baghdad. He and two other members of the 3rd Battalion of the 75th Ranger Regiment, based at Fort Benning, Georgia, were reportedly lured to their deaths by a woman they believed to be crying in distress.

Yesterday, dozens of photographs were spread across the coffee table: pictures of Russell’s life, from diapers to fatigues, and almost everything in between.

Joe, a retired Army Lieutenant Colonel and decorated veteran of two tours in Vietnam, always called his son, “Rusty,” even though he said Russell didn’t much care for the nickname. But he said they were as close as a father and son could get.

They talked often: about life in the military; about family, friends and the importance of continued faith. And Russell carried his Bible everywhere, Joe said — even to Iraq.

“Rusty knew the Lord,” Joe said. “I told him, get to know the Lord, so if you get hurt, you’ll be on a first-name basis. . . . We celebrate Rusty’s new assignment. Now he’s a soldier in the Lord’s army.”

Though they’ve been in their Montgomery Village neighborhood only since Wednesday, neighbors have stopped by to comfort them. “They brought food, flowers and hugs,” Rita said. Joe even heard from an old Vietnam buddy he hadn’t spoken to in 30 years, who had read about his son and called.

Russell grew up in Arvada, Colorado, his parents said, and was a high school homecoming king, captain of his soccer team and an Eagle Scout.

Rita said Russell was a thoughtful, caring person and always wore his heart on his sleeve. He also was gentle, prepared for battle but deeply concerned about his men.

“It’s not macho to give hugs, but Russell didn’t jeopardize who he was as a man to show affection,” she said. Rita said that one Valentine’s Day, she received an e-mail card from Russell. “It was a hug,” she said.

Joe talked about how Russell also appreciated time alone to reflect when he lived in Colorado.

“He liked to ride his Harley-Davidson,” he said. “He would take long rides and let the wind blow in his hair. He would go up in the mountains and look out over God’s creation. He would sit for hours.”

“It brought him peace and pleasure,” Rita said.

The last time Joe and Rita heard from Russell was the Saturday before he left for Iraq. They didn’t know where he was headed or how long he would be gone. Russell told his father, “I’ll call you when I get back.”

“He was trying to tell me something; he called three times that day,” Joe said. “It didn’t sink in. The only thing I regret is that I can say ‘I love you,’ but I can’t reach out and touch him.”

Joe and Rita said that they are proud of Russell’s accomplishments in the military (“He made captain before me,” said Joe) and that they are blessed to have had Russell in their lives for 27 years.

On Thursday, April 10, 2003, at 10 a.m., 40 Army Rangers from Fort Benning will be at Arlington National Cemetery to help the Rippetoes bury their son.

Rita squeezed a piece of tissue.

“Coming to terms with the fact that he won’t be around any longer is very difficult,” she said. But she said at least they know what happened to their son, unlike other military families whose sons and daughters may be missing.

“We’re not still waiting,” she said. “That part is over now.”

RIPPETOE, RUSSELL B

- CPT US ARMY

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: 07/21/2000 – 04/03/2003

- DATE OF BIRTH: 07/21/1975

- DATE OF DEATH: 04/03/2003

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 04/10/2003

- BURIED AT: SECTION 60 SITE 7860

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard