Name: Heinz Ahlmeyer, Jr.

Rank/Branch: O1/USMC

Unit: H & S Co., 3rd Recon BN, 3rd Marine Division, Khe Sanh, South Vietnam

Date of Birth: 06 February 1944

Home City of Record: Pearl River NY

Date of Loss: 10 May 1967

Country of Loss: South Vietnam

Loss Coordinates: 163706N 1064404E (XD845485)

Status (in 1973): Killed in Action, Body Not Recovered

Category: 2

Acft/Vehicle/Ground: Ground

Refno: 0678

Other Personnel in Incident: Malcolm T. Miller; James N. Tycz; Samuel A. Sharp

(all missing)

Source: Compiled by Homecoming II Project 01 April 1990 from one or more of the following: raw data from U.S. Government agency sources, correspondence with POW/MIA families, published sources, interviews. Updated by the P.O.W. NETWORK.

SYNOPSIS:

Third Class Petty Officer Malcolm T. Miller was a Hospital Corpsman assigned to H & S Company at Khe Sanh, South Vietnam. He was working with A Company, 3rd Marine Reconnaissance Battalion, 3rd Marine Division at Khe Sanh on May 9, 1967.

On that day, Miller joined a reconnaissance patrol from A Company that had the mission of gathering intelligence information on suspected enemy infiltration routes near their base. The patrol was helicopter lifted into an area just south of the DMZ, where they found signs of recent enemy activity, and moved to high ground to establish a night defensive position.

Shortly after 12 p.m. the patrol came under heavy small arms fire, and several of the team were wounded. Twelve hours later, after numerous unsuccessful attempts, a helicopter was finally able to land and retrieve the wounded. It was not possible to retrieve the bodies of those who had died, including Miller, LCpl. Samuel A. Sharp, Jr., Sgt. James N. Tycz, and 2Lt. Heinz Ahlmeyer, Jr. All were said to have died during the action from wounds received from enemy small arms fire and and grenades.

The four men left behind near the DMZ were never found. The government of Vietnam has been consistently uncooperative in releasing remains they hold or in allowing access to known loss sites.

Even more tragically, evidence mounts that many Americans are still alive in Southeast Asia, still prisoners from a war many have long forgotten. It is a matter of pride in the armed forces, and especially in the Marines Corps, that one’s comrades are never left behind. Many men have been killed trying to bring in a wounded or killed buddy. One can imagine the men missing from A Company, as well as Malcolm Miller, had they survived, being willing to go on one more patrol for those heroes we left behind.

9 May 2005:Nearly 40 years after they died on a hill in Vietnam, all that remained of four missing servicemen were some bone fragments and teeth. But the teeth were enough to identify them, finally bringing closure to families who could never bury their loved ones.

On Tuesday, three of the men will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery — including 20-year-old Navy Petty Officer Third Class Malcolm T. Miller of Tampa, Florida. The fourth man was buried in his hometown last month.

Miller’s older sister, Sandy Keheley of Madison, Georgia, says her father kept writing letters trying to get confirmation of his death, because no body had been recovered. She says the family finally accepted Miller’s death in the 1980s.

Since the end of the war, 748 Americans listed as missing in Vietnam have been accounted for. About 18-hundred servicemen are still missing from Vietnam.

9 May 2005:Every time Judy Ryan goes into the Pearl River, New York, library, she pauses to look at a plaque near the entrance dedicated to a young man she met in college — Heinz Ahlmeyer Jr.

“He was a sweet, unassuming person,” Ryan, a Yonkers native, recalled. “Just the nicest guy.”

Ahlmeyer grew up in a house on South Nauraushaun Road in Pearl River. He played football and baseball at Pearl River High School, and his friends said they never forgot him.

His sister, Irene Healea of Watertown, Tennessee, said her brother, whom she called “Junior,” loved the outdoors and hoped to have a career in forestry or teaching after graduating from the State University of New York at New Paltz.

Their father wanted him to go to college, so he put off enlisting in the Marine Corps until after graduation.

Ahlmeyer was in the officer candidates school at New Paltz, said Ryan, who met him at a sorority-fraternity mixer.

“He was on the soccer team, and I was a cheerleader,” she said.

Ahlmeyer’s parents never recovered from their loss, Healea said. Their father died several years later. Their mother, Aurelia, lived until July, never losing hope her son would, somehow, be found.

Another brother, Bill, was an Orangetown police officer until he died of cancer in 1986.

It was after 4 p.m. when the helicopter set down seven Marines on a rugged jungle hilltop 8 1/2 miles from Khe Sanh, an area in the Quang Tri province of Vietnam that was thick with enemy gunfire.

“We knew before we went out there were a large number of NVAs — North Vietnamese army — in the area,” Carl “Britt” Friery, then a 21-year-old private first class, recalled in an interview last week from his home in Colorado. “There was a good chance that we were going to see combat.”

But there was no way the seven Marines under the command of First Lieutenant Heinz Ahlmeyer Jr., a 23-year-old from Pearl River who had arrived in Vietnam the day before, could know the horror that awaited them on that hilltop May 10, 1967.

Of the seven Marines in the 1st Platoon, Company A, 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion, 3rd Marine Division, known as Team Breaker, only three made it back alive.

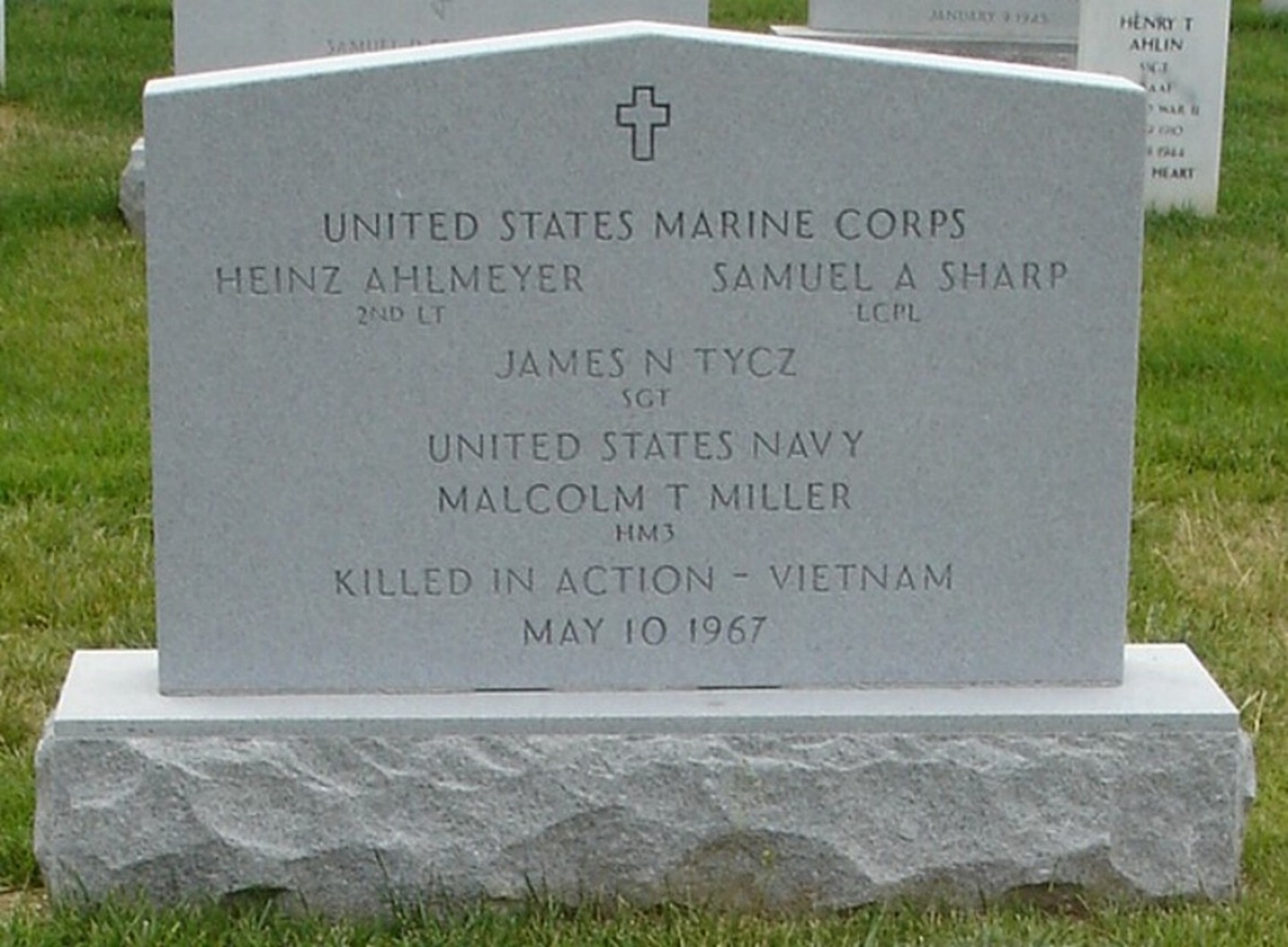

Remains of the four Marines killed in fierce combat that evening — Ahlmeyer, Samuel A. Sharp Jr., Malcolm T. Miller and James N. Tycz — will be buried tomorrow with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery, 38 years to the day after their deaths.

10 May 2005:What happened during that hilltop firefight at the height of the Vietnam War has haunted the survivors and the fallen Marines’ families ever since.

“I think about it a lot,” said Friery, now a 59-year-old former National Park Service employee who was disabled by post-traumatic stress syndrome. “The fact that we didn’t bring them home weighed heavily on my mind — there’s a lot of guilt.”

Ahlmeyer, the ranking officer, was the least experienced in the group. He was sent on the reconnaissance patrol in place of another officer who was about to return home.

Tycz had nearly finished his tour and was counting the days until he went home, Friery said.

The group came under heavy fire from all sides almost immediately, Friery said.

“We were pinned down by snipers,” he recalled. “Helicopters tried to pick us up, but they couldn’t get to us.”

Friery saw the four Marines die. Sharp was killed instantly by a gunshot to his head, Friery said. The others faced small-arms fire and grenades. Ahlmeyer had a severe wound to his abdomen and likely died soon after Sharp. Tycz was wounded but still tried to throw a grenade, which blew up on him, Friery said. Tycz and Miller probably died sometime that night, Friery said.

A helicopter — under constant attack — made its way to the three severely wounded survivors, Friery, Steven Lopez and Clarence Carlson, and plucked them to safety the next day.

There was never any doubt in Friery’s mind that the four were dead. He and the other survivors told commanders they had seen their four comrades killed.

But the four men’s families held onto the hope — no matter how improbable — that somehow their brother, their son, their uncle had made it off that hilltop alive.

“How do they know he was truly dead?” asked Dana Fisher, a Madison, Ga., resident who was born after Miller, her uncle, was presumed killed in combat. “Maybe he was just unconscious. We always believed that there was a chance.”

Tycz’s brother, Philip “Dale” Tycz of Plano, Texas, recalled his parents and siblings crowding around the television set in the early 1970s when prisoners of war were brought home.

“We kept on looking at the faces and hoping, hoping that we would see Neil,” he said. “But, of course, we didn’t and after a while, hope dimmed.”

The families knew there had been efforts over the years to retrieve the bodies.

Spokane, Wash., resident Janet Caldera, Samuel Sharp’s sister, was at a POW-MIA family association meeting in June when a military official told her unofficially that remains had been recovered in the area where the four were last seen.

“I was walking on air,” she said. “To think that he could be brought home and laid to rest in his country, not on foreign soil, meant so much to us.”

For their families and the men they served with in Vietnam, their burial 38 years later will bring a sense of peace.

“These men were not forgotten,” Tycz said. “When all the tears are shed Tuesday, I’ll know that I can look at my brother’s picture on the wall and know that he really is dead and he has been laid to rest with his comrades.”

Veterans groups prodded the U.S. government to keep up the efforts.

“These men and other men recovered since the end of the war would never have come home without a lot of good investigation,” said George Neville, a Montana resident who heads the Alpha Recon Association, a group of former members of the battalion. He said the remains were found in May 2003.

The survivors also helped find the missing Marines.

Friery said he asked military officials for a topographical map of the area, then showed investigators exactly where to look.

When Friery told a counselor during his treatment for post-traumatic stress that he dreamed of locating his fallen comrades, they told him it was fantasy.

“They said it was a delusion,” he recalled. “Well, now I know it wasn’t.”

The soil in that region is very acidic, so only the strongest parts of the bodies were identifiable after more than three decades, families were told. Most of the men were identified by their teeth.

Irene Healea, Heinz Ahlmeyer’s sister, was told her brother was identified by a single molar.

The remains will be placed in a metal box atop a full dress uniform in a casket for burial.

Separate ceremonies will be held for Ahlmeyer, Tycz and Miller. Sharp’s remains were buried last month in a cemetery near where his father is buried in San Jose, Calif.

A fourth casket containing bone fragments that could not be positively matched individually also will be buried in Arlington.

“Maybe God had a hand in that,” Caldera said. “They have been together for 38 years. He is not going to separate them now.”

10 May 2005:Four decades to the day after Malcolm Thomas Miller, a redheaded Navy petty officer from Tampa, perished on a blood- stained hill in a hellish corner of Vietnam, a military honor guard on Monday welcomed Miller and two comrades to hallowed earth at Arlington National Cemetery.

Their homecoming with full military honors ended a long forensic mystery and brought closure to three families and several veterans who last saw Miller firing his weapon and being hit by a grenade.

Some 300 people attended the ceremony, including grown relatives who had never seen the three men who died before they were born. Legendary General P.X. Kelley, onetime commandant of the Marine Corps, gave family members folded flags that had accompanied the remains from Vietnam via Hawaii.

Parts of the men were buried in four bright silver caskets, which glinted in the sun as ceremonial shots were fired and a bugler played taps. In each casket were teeth positively identified as belonging to each man. In the fourth were other teeth and bones probably belonging to the men but not conclusively identified.

“Although it has been nearly 40 years, the value of their sacrifice has not been diminished,” said Miller’s military clergyman, Navy Lieutenant Commander Robert Rearick.

Tom Sherlock, the cemetery’s historian, said the “repatriation” ceremony eclipsed all but perhaps a few. “This is the biggest group I’ve ever seen,” remarked Larry Greer, spokesman for the Defense Department’s Prisoner of War and Missing Personnel Office.

They included dozens of Vietnam veterans, members of Rolling Thunder, who zoomed in on glistening black motorcycles to present plaques marking the recovery of the bodies to the families. One by one, they also stepped up to each coffin, laid beads across the top as a tribute, and saluted.

Then a Native American member of the group sprinkled dust from a leather pouch and spread incense. In the crowd, grown men who remembered the battle brushed back tears and members of Rolling Thunder comforted the families with handshakes and hugs.

Wednesday, May 11, 2005

Families receive closure at burial services

As a U.S. Marine Corps band played taps and a hawk circled overhead, Phillip Dale Tycz said he felt his brother had finally come home.

“This is where I thought he belonged — not Vietnam ,” Tycz said.

For nearly four decades, the remains of Tycz’s younger brother, Marine Sgt. James Neil Tycz, 22, of Milwaukee , had been missing on a hill in Vietnam , along with those of three other servicemen killed in a firefight May 10, 1967.

On Tuesday, there were burial services for three of the men at Arlington National Cemetery ; the fourth had his service in his hometown of San Jose last month. A painstaking recovery effort by the military led to the identification of the remains earlier this year, using dental records.

“What came home physically was one tooth,” said Irene Healea, whose younger brother, Marine Second Lieutenant Heinz Ahlmeyer Jr., 23, of Pearl River , New York, was killed in the fight on Hill 665, near the Laotian border. “But what really came home was his embodiment and his spirit.”

More than 100 family members and friends came to pay their respects Tuesday, the 38th anniversary of the four young men’s deaths. Just before the service began, a Pentagon helicopter buzzed nearby, its whir-whir-whir a reminder of the fateful day in which a chopper retrieved the three survivors of the seven-man reconnaissance team, leaving the four dead behind. It was too dangerous to go back for them.

The silver-colored coffins reflected the sunlight of a perfect spring day, as a Marine marching band led a procession on the way to the grave site. Members of the POW-MIA group Rolling Thunder placed beads on the coffins. Each family was presented with a folded U.S. flag.

“The flag-folding was like watching a ballet,” said Sandy Keheley, the older sister of 20-year-old U.S. Navy corpsman Malcolm Miller, of Tampa, Florida “Seeing my brother as a hero today and not a statistic meant a lot to me. I feel his spirit is here. He’s on American soil.”

Marine Lance Corporal Samuel Sharp Jr., 20, of San Jose , California, was buried last month alongside his family members, but he was honored along with the other three at Arlington National Cemetery.

Sharp’s mother, Irene Sharp, said Tuesday was not a sad day.

“It’s been a relief to me,” she said. “No tears shed. Finally, he’s home.”

Sharp decided to sign up for the Marines after his best friend, Ed Charette, did. On Tuesday, Charette recalled telling his buddy: “What if you get killed, Sam? I’ll feel really bad.”

“I wish Sam and I had been here together to watch somebody else’s funeral,” Charette said. “I loved that guy.”

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard