NEWS RELEASES from the United States Department of Defense

No. 931-06 IMMEDIATE RELEASE

September 20, 2006

Navy Christens Littoral Combat Ship Freedom

The U.S. Navy will christen Freedom, the first littoral combat ship (LCS) at 10 a.m. EDT on Saturday, Sept. 23, during a ceremony at Marinette Marine Corp. in Marinette, Wisconsin.

The future USS Freedom acknowledges the enduring foundation of our nation and honors American communities from coast to coast which bear the name Freedom. States having towns named Freedom include California, Indiana, Maine, New Hampshire, New York, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and Wyoming. The 378-foot Freedom will be the first U.S. Navy ship to carry this class designation.

Birgit Smith will serve as ship’s sponsor. She is the widow of Army Sgt. 1st Class Paul Ray Smith, who was killed in action in Operation Iraqi Freedom and was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. The ceremony will be highlighted by Smith breaking a bottle of champagne across the bow to formally christen the ship, which is a time-honored Navy tradition. Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Mike Mullen will deliver the principal address at the ceremony.

A fast, agile, and high-technology surface combatant, Freedom will act as a platform for launch and recovery of manned and unmanned vehicles. Its modular design will support interchangeable mission packages, allowing the ship to be reconfigured for antisubmarine warfare, mine warfare, or surface warfare missions on an as-needed basis. The LCS will be able to swap out mission packages pierside in a matter of hours, adapting as the tactical situation demands. These ships will also feature advanced networking capability to share tactical information with other Navy aircraft, ships, submarines and joint units.

Freedom is the first of two LCS seaframes being produced. Freedom is an innovative combatant designed to operate quickly in shallow water environments to counter challenging threats in coastal regions, specifically mines, submarines and fast surface craft. The LCS is capable of speeds in excess of 40 knots and can operate in water less than 20 feet deep.

Freedom will be manned by one of two rotational crews, blue and gold, similar to the rotational crews assigned to Trident submarines. The crews will be augmented by one of three mission package crews during focused mission assignments. The blue crew commanding officer is Cmdr. Donald Gabrielson, who was born in northern Minnesota and graduated from the U.S. Navy Academy in 1989. The gold crew commanding officer is Cmdr. Michael Doran, who was born in Harrisonville, Mo., and graduated from Villanova University in 1989. Upon the ship’s commissioning in 2007, Freedom will be homeported at Naval Station San Diego, Calif.

In May 2004, the Department of Defense awarded both Lockheed Martin Corp., Maritime Systems & Sensors in Moorestown, N.J., and General Dynamics – Bath Iron Works in Bath, Maine, separate contract options for final system design, with options for detail design and construction of up to two flight 0 LCS ships.

In December 2004, the Navy awarded Lockheed Martin Corp. the contract for detail design and construction of the first LCS. Lockheed Martin’s teammates include Gibbs & Cox in Arlington, Va.; Marinette Marine Corp. in Marinette, Wis., where the ship is being built; and Bollinger Shipyards in Lockport, La.

For more information on the LCS, visit the Web site at https://peoships.crane.navy.mil/lcs/.

10 March 2005:

On Monday, the nation’s highest military award, the Medal of Honor, will be given to a soldier who served in Iraq, the first such award for that conflict.

Sgt. First Class Paul Ray Smith, a veteran of the first Gulf War, was 33 when died in combat in the early days of the current hostilities in Iraq.

President Bush will present his family with the medal on the anniversary of his death.

CBS News Correspondent Tracy Smith reports that the honor is so prestigious that Gen. George Patton once said he’d sell his immortal soul for that medal, and Harry Truman said he’d prefer it to being President.

But, notes Smith, that’s the story of the medal. This is the story of the man.

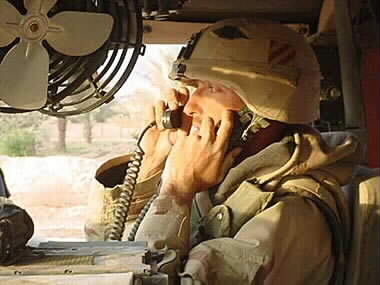

Sergeant Smith was deployed at the tip of the spear. He fought with the first wave of soldiers driving north to Baghdad, whipped by sandstorms, surrounded by the thunder of unfinished battle.

On the morning of April 4, 2003, while setting up a roadblock by Baghdad’s international airport, his company was surprised by a sudden storm of Iraqi fire.

“Things just started getting crazy, there were shots coming in from every angle,” Pvt. Michael Seaman of the 3rd Infantry Division said a few days later.

“I was going to be the first one to go through the wall, and he pushed me back and said, ‘No. I got this,'” recalled the 3rd Infantry’s Sgt. Matthew Keller.

With bullets blazing, Sgt. Smith jumped on a .50-caliber machine gun mounted on an abandoned truck and fired at three Iraqi positions, while single-handedly providing cover so his outnumbered soldiers could escape.

The Army says from 50 to 100 men were able to get to safety while Sgt. Smith was on that gun.

Smith was shot in the neck and killed.

“If it wasn’t for Sgt. Smith…everybody might not have got out as safe as they did,” marvels Pvt. Seaman.

The Medal of Honor that Sgt. Smith’s actions that day earned for him is the rarest distinction given to soldiers. It recognizes extreme bravery that goes beyond the call of duty.

The medal has not been awarded since 1993.

“He died a hero in my eyes. Nothing less,” says Pvt. Seaman.

On the day of the battle, Smith’s wife Birgit would write a letter to a husband who had already dead. “It never crossed my mind,” she says, “that Paul would die. Never. Not once. Not my man.”

Sgt. Smith and Birgit met in Germany in 1989. On their first date, inspired by his favorite movie, “Top Gun,” he serenaded her under her hotel window at 3 a.m.

“You have to picture him down on one knee,” Birgit says, “and having his arms up like that and singing, ‘I Lost That Loving Feeling.’ It was kind of romantic. You know, it was cool.”

But in 11 years of marriage, Birgit says, she would always come second: “It was first the army and boys, then the wife. …You learn to accept it, you know. He would have done anything for his boys.”

Sgt. Smith’s mother, Janice Pvirre says, “I am so humbled that our country is going to bestow this on my son.”

For a mother, even the Army’s highest honor is no consolation: “I guess it’s just another medal. It’s not going to bring my son home. I’m proud and I’m humbled. But it hurts,” she says, weeping quietly.

“So many people die in the Iraq war,” Birgit says. “But with Paul, he’s not a statistic. …I know that Paul will go into history, and his name will never, ever be forgotten.”

What does she think her late husband would think of getting the medal? “He probably sits up there and says, you guys are all crazy,” Birgit responded.

After two years, the family still feels the loss as if it happened yesterday.

Jessica, 18, and David, 11, are proud of the medal, but miss their dad.

“I get mad at him, because it’s really not fair for him to be up there and I’m down here,” David laments. “It’s like my best friend is gone now. …I would rather have him back than have the Medal of Honor.”

“Usually,” Jessica says, “the father walks the bride down the aisle. And I’m not gonna have that. You know, I won’t have him be there when I have grandchildren. He won’t be there for my graduation.”

“I still wear his ring,” Birgit says. “And as long as I have the ring on my finger and the breath in me, he will be my husband.”

The consummate soldier, Sgt. Smith made all of his men write a final letter home, in case they didn’t return.

Pvirre reads his aloud, crying: “As I sit here getting ready to go to war once again, I realize that I have left some things left unsaid. I love you and I don’t want you to worry. …There are two ways to come home: stepping off the plane, and being carried off the plane. It doesn’t matter how I come home, because I am prepared to give all that I am, to insure that all my boys make it home.”

David will be the one to receive the medal on Monday.

29 March 2005:

White House to award first Medal of Honor for service in Iraq

The first Medal of Honor awarded for service in Iraq will be presented next Monday in a ceremony at the White House, White House spokesman Scott McClellan announced Tuesday.

For the family of Sergeant First Class Paul R. Smith, the honor, the nation’s highest military award, brings conflicting feelings: pride that he’ll be remembered among America’s bravest soldiers, grief that he died two years ago in Iraq.

“At least my mind is at rest because with the Medal of Honor, Paul’s name will go on in history,” his wife, Birgit Smith, said Tuesday from her home in Holiday, Florida. “His name will never die. This is very important to me.”

President Bush will present the medal to Smith’s 11-year-old son, David, during the White House ceremony, Birgit Smith said.

There’ll be a second ceremony next Tuesday morning at the Pentagon. Then in the afternoon, the family will attend another ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery, where Smith’s headstone will be unveiled.

Smith was nominated for the Medal of Honor by commanders of the 3rd Infantry Division after his death on April 4, 2003.

Smith, 33, died behind the trigger of a .50-caliber machine gun as he fought off an Iraqi attack near Baghdad’s international airport. He’s credited with saving more than 100 American lives and killing at least 50 Iraqis.

“This was something beyond the call of duty,” said Colonel Will Grimsley, one of the commanders who signed the medal nomination. “But with a guy like him you knew what he would do to take care of his guys.”

Smith, who also served in the 1991 Persian Gulf War, was well-known among his soldiers for being demanding, insisting on constant training to prepare them for combat.

Birgit Smith said she thought Smith would have been embarrassed by the honor.

“Paul would think `wow,’ and shy away from all the attention,” she said. “He would want to share the recognition with his soldiers.”

The past two years have been hard on the Smith family. Besides his wife and son, Paul Smith left behind a daughter, Jessica, 18.

The family moved from Hinesville, Georgia, to Florida after his death. They live in the house where Paul Smith grew up. His parents live nearby.

The family thinks of him every day, said Lisa DeVane, a sister of his who lives near Atlanta.

“We’ve waited so long for this,” she said. “We’re so proud, but it doesn’t diminish the fact his loss is enormous in our personal lives.”

March 29, 2005

Soldier to be awarded

Medal of Honor

By Matthew Cox

Courtesy of the Army Times

The Army announced Tuesday Sergeant First Class Paul Ray Smith will be the first soldier from Operation Iraqi Freedom to receive nation’s highest award for valor — the Medal of Honor.

In an April 4 ceremony at the White House, President Bush will present the Medal of Honor to Smith’s wife, Birgit, his 11-year-old-son, David, and his 18-year-old daughter, Jessica. The ceremony will mark the two-year-anniversary of the day Smith died while leading a counter-attack against a much larger Iraqi force.

Smith’s unit, 2nd platoon, B Company, 11th Engineer Battalion, had been ordered to set up a temporary prisoner of war holding facility during 3rd Infantry Division’s seizure of Saddam International Airport.

When the unit moved into a courtyard, an enemy force that eventually grew to 100 Iraqi soldiers attacked with mortars, automatic weapons and rocket propelled grenades.

At the height of the battle, Smith ordered one soldier to back a damaged M113 armored personnel carrier into the courtyard between the enemy and members of his unit.

The Medal of Honor citation described the scene:

“Knowing the APC’s .50-Cal. machinegun was the largest weapon between the enemy and the friendly position, Sgt. 1st Class Smith immediately assumed the track commander’s position behind the weapon, and told a soldier who accompanied him to ‘feed me ammunition whenever you hear the gun get quiet.’ Sgt. 1st Class Smith fired on the advancing enemy from the unprotected position atop the APC and expended at least three boxes of ammunition before being mortally wounded by enemy fire.

The enemy attack was defeated. Sgt. 1st Class Smith’s actions saved the lives of at least 100 soldiers … and resulted in an estimated 20-50 enemy soldiers killed.

His actions inspired his platoon, his Company, the 11th Engineer Battalion and Task Force 2-7 Infantry.”

His wife, Birgit, said she is “thrilled and humbled” that her husband will receive such a prestigious award, but also that his name will become part of history.

“Paul is not a statistic; his name will live on forever,” said the 38-year-old during a telephone interview from her Holiday, Florida, home.

Birgit added that she never was surprised by her husband’s sacrifice.

“Paul loved his country,” she said. “He loved the Army, and he loved his soldiers.”

Tuesday March 29, 2005

MEDAL OF HONOR

‘I am prepared to give all that I am … ’

Paul Smith held off an attack by Iraqi forces on April 4, 2003, in the battle to take Saddam International Airport outside Baghdad ‘to ensure that all my boys make it home.’ The U.S. military is expected to posthumously give Smith its highest award — the Medal of Honor, the first of the Iraq war.

By NOELLE PHILLIPS

Sergeant First Class Paul R. Smith wrote a letter to his mother days before his Army unit crossed into Iraq as part of the U.S. invasion.

His words were chilling in their foreshadowing:

“There are two ways to come home, stepping off the plane or being carried off the plane. It doesn’t matter how I come home, because I am prepared to give all that I am to ensure that all my boys make it home.”

He saved the letter on his laptop but never mailed it.

Smith was killed on April 4, 2003, firing a .50-caliber machine gun to save the lives of more than 100 American soldiers.

Now, the U.S. military is expected to posthumously give Smith its highest award — the Medal of Honor. The Army Times, citing a March military public affairs conference and unnamed Pentagon sources, reported Monday that an announcement is coming.

The White House is expected to present the medal to Smith’s family during an April ceremony in Washington, D.C. It had no announcement Monday, a spokesman said.

Smith will be the first soldier who fought in Iraq to receive the award.

Many of the nation’s 3,440 Medal of Honor recipients have become heroes in American history and pop culture. Their stories fill books and flicker across movie screens. Nearly 18 percent of them, including Smith, were killed in action, according to military records.

Smith will be recognized for climbing inside the gunner’s hatch of an armored personnel carrier while his unit fought outside the Saddam International Airport.

At 6 feet 2 inches tall, Smith was a vulnerable target. Still, he held off a wave of Iraqi Special Republican Guard soldiers before an enemy bullet finally hit his throat.

Army accounts of the fight report Smith killed more than 50 Iraqis in the gunbattle.

When Smith died at age 33, he left behind a wife, Birgit; a daughter, Jessica, then 17; and a son, David, then 9.

He had joined the Army out of high school in 1989.

Smith fought in Operation Desert Storm, where he lost a friend in combat. Family said the experience cemented his determination to be a top-notch soldier.

Birgit Smith met her husband when he was serving in Germany, and the two started dating before he left for Desert Storm.

“I knew a boy, and all of a sudden he came back a man,” Birgit Smith said in a 2003 interview.

As Smith earned promotions through the enlisted ranks, he gained a reputation for being tough.

“I knew why he did it,” Birgit Smith said. “He wanted to prepare all the guys for the real life. The Army is not a joke.”

AIRPORT ATTACK

Once Smith’s 11th Engineer Battalion arrived in Kuwait in early 2003, Smith hounded his soldiers to be perfect in their war preparations. He rode their backs about cleaning weapons and trained every soldier to operate a .50-caliber machine gun.

The 11th Engineer Battalion was part of 3rd Infantry Division’s Task Force 2-7. As part of the division’s 1st Brigade, the task force would help capture Saddam International Airport in Baghdad.

Around dawn on April 4, Smith’s platoon arrived at the airport after driving all night. Fellow soldiers said Smith did not sleep as he guided his troops across the Euphrates River and through villages and farms.

Task Force 2-7 blocked highways around the airport to hold off enemy reinforcements.

Gunfire popped in the distance, but Smith gave his platoon time to eat, clean up and rest. Nearby, the task force’s operations center ran the airport battle; medics treated wounded soldiers in an aid station; and a mortar platoon nearby was ready to fire.

Smith’s platoon was called to duty to build a holding cell for captured Iraqis.

A courtyard with a guard tower seemed to be the perfect place, even though it was part of a Special Republican Guard complex. But Iraqi fighters attacked as the engineers burned brush and strung concertina wire.

Smith directed his soldiers to shoot their M-16 rifles. He threw grenades and fired an anti-tank missile.

An enemy grenade slammed into an American armored personnel carrier, wounding three soldiers inside. Smith oversaw their evacuation.

Smith and two privates were left to hold off the Iraqis.

The most powerful weapon in the courtyard was a .50-caliber machine gun mounted on the roof of the armored carrier.

Smith climbed inside the carrier’s gun hatch and ordered Pfc. Jonathan Seaman to drive into the courtyard’s center. But the carrier was towing a trailer that had jackknifed. It wouldn’t budge.

Smith ordered Pfc. Gary Evans to get out and detach the trailer. He gave Seaman specific instructions, too: If the machine gun stopped, hand up another box of ammunition.

Then, Smith fired.

‘HIS WHOLE BODY COLLAPSED’

Meanwhile, 1st Sgt. Timothy Campbell, the senior enlisted man in Smith’s company, organized an attack on the guard tower where Iraqis were hiding.

Campbell knew as long as he could hear Smith’s gun, his group had cover.

Campbell’s group reached the tower and unloaded a barrage of bullets through its windows. When they stopped firing, the whole battlefield had gone quiet.

Inside the armored personnel carrier, Smith’s machine gun stopped. Seaman turned to hand Smith another box of ammo.

“I still saw his legs standing up there,” Seaman said in an interview after the war. “I blinked my eyes, and his whole body collapsed into the tank.”

The engineers carried Smith to medics, who tried for 45 minutes to revive him.

When medics placed a blanket over Smith’s face, his fellow soldiers knew they had lost a hero.

‘WHATEVER IT TAKES’

It would be several hours before two uniformed officers knocked on the Smith family’s front door to tell about his death.

Birgit Smith lived in Hinesville, Georgia, near the 3rd Infantry Division’s headquarters at Fort Stewart. She said she had watched enough war movies to know why the officers were there.

At first, she begged them to double-check because Smith is a common name. Then, she grew angry and asked them to leave.

Birgit Smith and her children wouldn’t realize what a hero Paul Smith had become until she read articles written by embedded reporters. In fall 2003, the 11th Engineer Battalion’s soldiers came home with their stories.

Birgit Smith said in 13 years of marriage Paul spent more time with the Army than at home — a typical problem for a soldier.

As hard as Paul pushed his soldiers at work, his behavior at home was lovable and attentive.

Because of those characteristics, Birgit said she was never surprised that Paul Smith would risk his life to save others.

“That’s what Paul was. He was always taking care of others,” she said in 2003. “He was always so concerned about bringing his soldiers home. He would do whatever it takes.”

Sergeant First Class Paul R. Smith, who spent his boyhood in Tampa, became a man in the Army and died outside Baghdad defending his outnumbered soldiers from an Iraqi attack, will receive America’s highest award for bravery.

President Bush will present the Medal of Honor to Smith’s wife, Birgit, and their children Jessica, 18, and David, 10, at a ceremony at the White House, possibly in March.

The official announcement will come soon, but the Pentagon called Mrs. Smith with the news Tuesday afternoon.

“We had faith he was going to get it,” Mrs. Smith said from her home in Holiday, “but the phone call was shocking. It was overwhelming. My heart was racing, and I got sweaty hands. I yelled, “Oh, yes!’ … I’m still all shaky.

“People know what’s he’s done … people know that to get a Medal of Honor you have to be a special person or do something really great.”

What Paul Smith did on April 4, 2003, was climb aboard an armored vehicle and, manning a heavy machine gun, take it upon himself to cover the withdrawal of his men from a suddenly vulnerable position. Smith was fatally wounded by Iraqi fire, the only American to die in the engagement.

“I’m in bittersweet tears,” said Smith’s mother, Janice Pvirre. “The medal isn’t going to bring him back. … It makes me sad that all these other soldiers have died. They are all heroes.”

With the medal, Smith joins a most hallowed society.

Since the Civil War, just 3,439 men (and one woman) have received the Medal of Honor. It recognizes only the most extreme examples of bravery – those “above and beyond the call of duty.”

That oft-heard phrase has a specific meaning: The medal cannot be given to those who act under orders, no matter how heroic their actions. Indeed, according to Library of Congress defense expert David F. Burrelli, it must be “the type of deed which, if he had not done it, would not subject him to any justified criticism.”

From World War II on, most of the men who received the medal died in the action that led to their nomination. There are but 129 living recipients.

Smith is the first soldier from the Iraq war to receive the medal, which had not previously been awarded since 1993. In that year, two Army Special Forces Sergeants were killed in Somalia in an action described in the bestselling book Black Hawk Down.

The officer who called Birgit Smith on Tuesday nominated her husband for the medal.

Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Smith (no relation) sent in his recommendation in May 2003, beginning a process that involved reviews at 12 levels of the military chain of command before reaching the White House. On Tuesday, Colonel Smith expressed satisfaction that the wait was over, and great admiration for his former subordinate.

In the Army, he said, you hear about men who won the Medal of Honor. “You think they are myths when you read about them. It’s almost movielike. You just don’t think you’d ever meet someone like that.”

Paul Smith, he said, was not a “soft soldier” who suddenly got tough under fire. “This was a guy whose whole life experience seemed building toward putting him in the position where he could do something like this. He was demanding on his soldiers all the time and was a stickler for all the things we try to enforce. It’s just an amazing story.”

Colonel Smith commanded the 11th Engineer Battalion, 3rd Infantry Division, during the American attack on Iraq, which began March 20, 2003. On the morning of April 4, the engineers found themselves manning a roadblock not far from Baghdad International Airport.

A call went out for a place to put some Iraqi prisoners.

Sergeant Smith volunteered to create a holding pen inside a walled courtyard. Soon, Iraqi soldiers, numbering perhaps 100, opened fire on Smith’s position. Smith was accompanied by 16 men.

Smith called for a Bradley, a tank-like vehicle with a rapid fire cannon. It arrived and opened up on the Iraqis. The enemy could not advance so long as the Bradley was in position. But then, in a move that baffled and angered Smith’s men, the Bradley left.

Smith’s men, some of whom were wounded, were suddenly vulnerable.

Smith could have justifiably ordered his men to withdraw. Colonel Smith believes Sergeant Smith rejected that option, thinking that abandoning the courtyard would jeopardize about 100 GIs outside – including medics at an aid station.

Sergeant Smith manned a 50-caliber machine gun atop an abandoned armored personnel carrier and fought off the Iraqis, going through several boxes of ammunition fed to him by 21-year-old Private Michael Seaman. As the battle wound down, Smith was hit in the head. He died before he could be evacuated from the scene. He was 33.

Sergeant Matthew Keller was one of the men who fought with Smith in the courtyard. “He put himself in front of his soldiers that day and we survived because of his actions,” Keller said Tuesday from Fort Stewart in Georgia. “He was thinking my men are in trouble and I’m going to do what is necessary to help them. He didn’t care about his own safety.”

Some of the men who fought alongside Smith were sent back to Iraq last month. Keller, 26, is scheduled to return February 15, but was scrambling Tuesday to delay his deployment to attend the medal ceremony in Washington.

“I want to be there to support the family and show thanks for what Sergeant Smith did,” Keller said.

Mrs. Smith moved to Holiday after her husband’s death, to be near his parents. Her daughter, Jessica, recently moved out on her own and is thinking about going to college. Son David is a fifth-grader at Sunray Elementary School in Holiday.

“From the beginning (David) didn’t show much feelings, keeping to himself,” Mrs. Smith said. “He thinks if he brings it up it will make me sad. He’s trying to be the strong one. The day Paul left for Iraq he told David, “You’re the man in the house now.’

“Paul is not forgotten,” she said. “He’s part of history now. It makes me feel proud, so honored that I was allowed to be part of Paul’s life. Even today he’s probably laughing at all of us, saying “You’re making way too big a deal out of me.’

“He did what he had to do to protect his men, not to get a medal.”

January 25, 2004

The GIs were dirty, mosquito-bitten, fatigued, homesick. They had been on the road almost constantly for two weeks. Many had not slept in days.

At dawn on April 4, 2003, they arrived at Saddam International Airport to the sound of sporadic gunfire and the acrid smell of distant explosions. Breakfast was a mushy, prepackaged concoction the Army optimistically calls “pasta with vegetables.”

Still, the mood was upbeat.

Reaching the airport meant the war was almost over. Some of the men broke out cheap cigars to celebrate.

Afterward, Sergeant First Class Paul R. Smith and his combat engineers set about their mission that day, putting up a roadblock on the divided highway that connects the airport and Baghdad. Then, just before 10 a.m., a sentry spotted Iraqi troops nearby. Maybe 15 or 20. By the time Smith had a chance to look for himself, the number was closer to 100.

Smith could oppose them with just 16 men.

He ordered his soldiers to take up fighting positions and called for a Bradley, a powerful armored vehicle. It arrived quickly and opened fire. The Americans thought they were in control until, inexplicably, the Bradley backed up and left.

“Everybody was like, “What the hell?”‘ said Corporal Daniel Medrano. “We felt like we got left out there alone.”

The outnumbered GIs faced intense Iraqi fire. Whether they would survive the next few minutes hinged largely on Smith. He was 33 years old, a 1989 graduate of Tampa Bay Vocational-Technical High School, a husband and father of two.

To his men, Smith was like a character in the old war movies they had watched as kids, an infuriating, by-the-book taskmaster they called the “Morale Nazi.”

But Smith had spent much of his adult life preparing for precisely this moment. Indeed, in a letter to his parents composed just before the war, he seems to have anticipated it:

There are two ways to come home, stepping off the plane and being carried off the plane. It doesn’t matter how I come home because I am prepared to give all that I am to ensure that all my boys make it home.

Uncommon valor

What explains Smith’s commitment to his men?

Few clues are to be found in the story of his early years, growing up in Tampa’s Palma Ceia neighborhood. He and three siblings were raised by a single mother who worked two jobs to support the family. Smith was a so-so student, not much of an athlete, not particularly popular. His childhood was altogether unremarkable.

He studied woodworking in high school and did trim work for a contractor. After graduating in June 1989, Smith joined the Army. He was motivated not by patriotism but a desire to find a job offering more stability than the paycheck-to-paycheck life of a carpenter. As a new recruit, Smith left an impression of someone more interested in partying than, say, marksmanship.

But by the time he got to Saddam International Airport, Smith was a different man, a master of the soldier’s art. On April 4, in the words of his commanding officer, Smith displayed “extraordinary heroism and uncommon valor without regard for his own life in order to save others . . . in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service. . .”

What Smith offered his men, Abraham Lincoln, in an earlier age, called “the last full measure of devotion.”

A quarter-million Americans have served in the Iraq war. Paul Ray Smith is the only one thus far nominated for the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest award for bravery.

Since the start of World War II, just 842 men have received the Medal of Honor. Almost two-thirds were killed in the action for which they were nominated.

“If the Medal of Honor today has an intangible and solemn halo around it,” wrote author Allen Mikaelian, “it is partly due to those men who did not survive to wear it.”

General George Patton said he would give his soul for one. Lyndon Johnson and Harry Truman said they would rather have the medal than be president.

By law, the Medal of Honor is awarded by the president only to those in the armed services who distinguish themselves “conspicuously by gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of (their lives) above and beyond the call of duty.”

“Above and beyond the call of duty” has a specific meaning. The medal is not awarded to those who act under orders, no matter how heroic their actions. In fact, according to Library of Congress defense expert David F. Burrelli, it must be “the type of deed which, if he had not done it, would not subject him to any justified criticism.”

Given the extraordinarily high standard, it is far from certain Smith will be awarded the Medal of Honor. But his story is as much about professionalism as it is heroism. He had thought about what it means to lead men in combat. He knew that men will more willingly follow a superior who exposes himself to danger, shares their hardships, shows concern for their welfare.

On April 4, Smith did all of those things.

It was 13 years ago when Birgit met a young soldier, Paul Smith, in Germany. He got down on one knee to sing the song ‘You’ve Lost That Loving Feeling’ from the movie Top Gun. In 1992, that soldier became her husband. And on April 4, 2003, she lost him in the Iraqi conflict.

U.S. Army Sergeant First Class Paul Smith was deployed for Iraq the day before the couple’s 11th wedding anniversary. As a Combat Engineer, he was part of the group that found and destroyed enemy weapons, and built bridges for troops to travel across to different areas. On the day he died, dozens of Iraqis started firing behind a wall. Perched on top of a military vehicle, Sergeant Smith began firing 300 rounds of ammunition, killing 50 Iraqis. He went down, and his actions possibly saved 100 of his own men.

Birgit is not surprised by her husband’s actions. He received the Bronze Star and the Purple Heart, and is now nominated for the highest military honor, the Medal of Honor. But to a widow who must care for her teenage daughter and young son, the Medal means nothing to her. She says he’s a hero, not because he saved lives, but because he was a loving husband and father who took care of his family. Things he may not receive a medal for, but to her that’s biggest honor of all.

Army Sgt. 1st Class Paul Smith:

Soldier, Leader, Hero

This article was written shortly after the events of April 4, 2003, that led to Sergeant First Class Paul Smith’s death. Three days later, Staff Sergeant Lincoln Hollinsaid, who was quoted in this article, was also killed in action.

UNDISCLOSED TACTICAL LOCATION, Iraq — “He took the hard right over the easy wrong.”

“He always set the example; he was a professional who lived by the creed of the noncommissioned officer.”

“He accomplished the mission, exceeding the standard, and always made sure his soldiers were taken care of.”

Ask any soldier in Company B, 11th Engineer Battalion, and their thoughts on Sergeant First Class Paul Smith, 2nd platoon sergeant, would reflect those of Staff Sergeant Lincoln Hollinsaid, a squad leader in that platoon.

Smith was killed April 4 east of Baghdad International Airport when his platoon came under attack from Iraqi forces numbering more than 100.

SMITH, PAUL RAY

- SFC US ARMY

- IRAQ

- DATE OF BIRTH: 09/24/1969

- DATE OF DEATH: 04/04/2003

- BURIED AT: SECTION MD SITE 67

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard