Michael John Allard was born on September 12, 1940 and joined the Armed Forces while in Schofield, Wisconsin.

He served as a 1315 in the Navy. In 4 years of service, he attained the rank of Lieutenant/O3. He began a tour of duty on August 30, 1967.

For 34 years, all that Mark, Paul and Bart Allard knew about their father came from mementos, pictures and family stories.

That changed March 19, when Mike Allard’s remains were laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

Allard, a Navy pilot, was killed in a 1967 airplane crash in Vietnam. The Wausau, Wisconsin, native was listed as missing in action, because the body was not recovered.

Our brother, Mike Allard, is no longer a MIA from the Vietnam War; his remains have been identified. There will be a memorial at Arlington Cemetery on Monday, 3/19/01. He and Tom Urban will be flying out for this memorial. Perhaps others might

attend as well.

Regards,

Mark

Friends of Mike Allard,

I am attaching a message I received today from Denny Allard Higgins. I forwarded your messages to her last week via e-amail, and I will take printed copies to the service with Mike’s 1958 football photo scanned onto the cover. As you can see, she really appreciated the letters many of you sent as well as the other messages she has gotten. I am sending this because I thought everyone would want to know all the details of Mike’s three children and their families. Many of us, including me, did not know until recently that Mike had left three boys behind. As I reread this, it is possible that Denny has already sent this information to all of you, but it is not evident from the addressing.

Also, for those who had asked about a reception after the gravesite service, that information is included in the letter. I wrote Denny that 4 Marquette fraternity brother would be attending. Incidentally, the Navy website had a start time of 8:15 for the service, and that is what I have been telling people, but I heard from Phil Walsh, a retired Marine and Marquette fraternity brother of Mike’s yesterday that he has contacted the person in charge of funeral arrangements at Arlington and he was given a start time of 8:45. He advises that the person to contact is Mr. Tony Carter, Funeral Honor Support (WNY). Also, note that the Wausau paper and TV stations are doing stories on Mike, which some of you have contributed to. The newspaper will run the story on March 18. I do not know about the TV schedule.

Mancer Cyr

Denny’s letter follows:

Dear Mancer,

I look forward to meeting you in Washington, March 19th. I truly am touched by your efforts to organize letters and thoughts of people who knew Mike in Wausau and Milwaukee. The common thread that I noticed in the letters was that Mike was a sensitive, nurturing, smart, and fun-loving person. What a joy! We will be staying at the Hilton Washington & Towers in DC — on Connecticut Ave at Dupont Circle. What I would like to share with all of you is that Mike did leave a living legacy of three wonderful, sensitive, nurturing, smart, and fun-loving sons. Mark is 36 years old and married to Julie. Their two children are Michael (age 7) and Grace (age 5). Mark is an orthopeadic surgeon with Ozark Orthopeadic and Sports Medicine. Paul is 35 years old and married to Debbie. Their two children are Greg (age 7) and Olivia (age 4). Paul is a Mechanical Engineer with Glad Manufacturing . Bart is 34 years old and married to Missy. They are expecting their first child in May. Bart is a CPA and owns his accounting firm Lundy-Allard. I am sure that Mike has guided us in our lives and been a powerful force from heaven. In regard to the Wausau paper doing an article — that would be just fine. The Wausau TV station just did or is doing a story and I sent a group of pictures to a man named Greg Mulberg at the station. Perhaps your friend could use some of them before they are mailed back to me. Thank you again for all you have done and we do look forward to meeting you — do you have a family that will be with you? We are having a reception at the Sheraton Hotel right next to Arlington Cemetary after the Mass and interment. I would love for all those who come to help us put Mike in his final resting place to come and have a light brunch with us. There will be directions passed out at the service.

Sincerely,

Denny Higgins

Wausau Daily Herald

March 18, 2001

“Wausau pilot to be buried after 34-year wait

By Peter J. Wasson

Wausau Daily Herald

A box of old and dusty bones will be lowered into the Virginia earth Monday, drawing to a close the story of Wausau native Mike Allard — a story that has taken 34 years to be fully told.

Bones are all that is left of Allard, all that could be found of the 26-year-old pilot who went enthusiastically to Southeast Asia in 1967 to fight for democracy and freedom.

His remains moldered over the decades on a Vietnamese hillside as his three children grew to adults and had children of their own, and as his widow went on to find a career and new husband.

But when the bones were found four years ago and later identified, phones started ringing as friends and family members recalled the extraordinary young man who drew them together so long ago.

When Allard finally is laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery on Monday, almost 100 people will gather to say goodbye.

“This has all hit me harder than I thought it would,” said Allard’s widow, Denny Allard Higgens. “It’s just something that happened, a big part of my life, and I don’t think we ever stop loving or caring. We just put it in a quiet place, and now it’s been brought back up. I’m sort of shocked at the strength of my emotions over time. We all have this little thing inside: What would life have been like if Mike had lived?”

The young Mike Allard

Allard was born in Wausau in 1940, and even as a child, characteristics that would lead him to life as a fighter/bomber pilot were emerging.

In junior high school and high school, he played football and curled on class teams. By his junior year in high school, Allard was on the Student Council and had moved up to the “A” squad of the varsity football team.

“He was a kid who was incredibly reckless with his body,” said Mike Brockmeyer, 61, who was a quarterback on the team. “He threw it around and had no fear. It made him a good football player and probably a good pilot as well.”

Becoming a pilot already was in Allard’s mind because his older brother, Dave, had graduated high school and gone on to the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis. Dave Allard served as a helicopter pilot for five years, leaving the Navy as the war in Vietnam was beginning.

“He would never have admitted that he was sort of following me, but I think he was,” said Dave Allard, 65, who now lives in California. “I played a lot of football and so did he. He would never admit he envied my appointment to Annapolis, and he did go into ROTC. But I think he always envied my flying.”

After high school, Mike Allard went on to Marquette University in Milwaukee where, as his brother said, he joined the Reserve Officers Training Corps and began planning a career in the military.

He was an engineering major and met Tom Grossman, the man who was to become his closest friend, when both joined the Sigma Phi Delta engineering fraternity.

“He was a real gung-ho guy,” Grossman said. “He really looked forward to the naval career right when he got out of school.”

Grossman, now a 60-year-old California real estate broker, recalls the summer when Allard met Denny — short for Denise — and the two began dating.

“They had a real close relationship real quick,” Grossman said. “He was kind of a wild and crazy guy at the time, and she was a lot of fun but with a serious side. She knew how to lash him down when he got too wild.”

Life in the Navy

Denny said she and Mike decided they were one another’s future during her junior year at Marquette.

“I figured it out the next summer, the year he graduated,” she said. “There’s a grotto to the Blessed Mother near Blue Mound in Milwaukee, and he got down on his knees and proposed. I remember it like it was yesterday.”

Denny and Mike started a family and had three children, all boys: Mark, now 36 and an orthopedic surgeon, Paul, 35, an engineer like his father, and Bart, 34, who owns an accounting firm.

By the time Mark was born, Allard’s immediate future was certain. He would be in what sailors called the “black-shoe Navy,” which means he would serve on a ship, eventually serving aboard a landing ship stationed in California.

But his ultimate desire was to fly, and after about a year aboard the landing ship, he was accepted into flight school, where he learned to fly an A-4 Skyhawk, an attack plane designed to drop bombs and shoot missiles at ground targets. One of his instructors was a young pilot named John McCain, who went on to become an Arizona senator and 2000 presidential candidate.

When Allard left California for Southeast Asia, the war still was in its infancy.

It wasn’t until late 1967, after increasing casualties and President Lyndon Johnson’s request for increased taxes to fund the war effort, that public support for the conflict began eroding.

When Allard left, popular opinion held that the U.S. military power would quickly crush the Vietnamese and that soldiers, pilots and sailors were in no real danger.

“It was before all the protests and everything,” Grossman said.

Just before Allard shipped out, Grossman went on a day cruise for friends and family aboard Allard’s aircraft carrier, the USS Coral Sea.

“The possibility of him dying, it never even crossed my mind,” Grossman said. “I saw how organized everything was, how the Navy ran, and I had the impression we were going to a country with no capability to be very formidable to us, at least from the air. Mike was really excited about going and serving his country and being able to fly. After the cruise, I hugged him goodbye and said ‘I’ll see you when you get back,’ and that was the last time I saw him.”

Allard’s widow didn’t share Grossman’s optimism at the time because she lived on a naval base and saw the families of dead pilots every day. After seven or eight months of training, Allard’s carrier left for the South China Sea.

“We all went to the ship, and right now I can see him up on the ship when he pulled out,” Denny said. “I knew he was going into combat, but I had every expectation that he would return. It just didn’t work out that way.”

Missing in Vietnam

Only the Navy knows exactly what happened to Allard over the next several weeks. There’s no question that, once on station, he and other pilots spent time training and preparing for missions.

But details are sketchy because, even now, information about Allard’s duties and missions is classified.

Allard stayed in touch with his older brother, who then was living in Detroit, by sending audio tapes back and forth. Mike told Dave as much as he could, and Dave sent him recordings of Green Bay Packers games.

“He sent a few back, telling me he was flying and things like that,” Dave Allard remembered. “He was really, really happy with Navy life.”

In late August, Allard flew his first combat mission. Dave Allard said he suspects that first mission was a bombing run against an unfortified position and that his little brother did not face enemy fire.

It was on his second mission that Allard ran into trouble. On Aug. 30, 1967, Allard and his wingman — the pilot who flew by Allard’s side — were assigned to attack an enemy emplacement just north of the South Vietnam border.

Allard dove on the target and, for some reason, was unable to pull out of the dive. His plane was either hit by enemy fire or it stalled.

Denny learned of her husband’s death a few days later — two weeks before Allard would have turned 27 — when the base commander and a chaplain came to her California home.

Allard was missing in action and presumed dead, they told her.

“After I talked to his wingman, I didn’t have any doubts,” Denny said. “They weren’t allowed to tell us exactly what they were doing, but they were low-flying attack aircraft so I can guess. He didn’t know what hit him.”

The Navy held a quiet memorial service for Allard in California a couple of weeks after he was shot down. His body remained on an unnamed hillside in Vietnam.

“I don’t think it had much of a bearing,” Denny said. “The loss is there whether you put someone in a box or not. The loss was real, no matter what the circumstances. He was gone.”

Life after Mike

Denny was given 30 days to move herself and her three children off the naval base in California. She had a journalism degree from Marquette but had never planned on being anything but a mom and wife.

She packed up Mark, Paul and Bart and returned to her family home in Oklahoma City.

“It was very difficult,” she said. “But once again, for me personally, I had a lot of faith that God would support me and I would get the help I needed raising my kids. You mourn people who die and you grieve, but you go on and live your life. I didn’t want my children scarred by the Vietnam War or the loss of a father. I prayed a lot about it, and I think Mike helped us a lot from heaven.”

Over the next few months and years, Allard’s friends learned of his death through conversations with other friends and letters from home.

Grossman, who grew up in Appleton but eventually moved to California, still laments the loss of his friend.

“He’s been missed for all these years but not forgotten,” Grossman said. “That’s the best anyone can ask for, that we’re retained in someone’s memory when we’re gone. He still occasionally pops into my head, and it’s always been something that amazes me. I’ll see his face and that’s just never gone away — it happens a couple of times a year. He was probably the first friend I ever lost, and it was a big shock.”

In 1997, Denny married a book publisher named Ray Higgens and the family moved to Rogers, Ark., where Denny is a school principal.

Over the years, she has recalled her first husband frequently. And when the Vietnam War Memorial Wall was built in 1982, she made sure all of Mike’s children visited it.

“They don’t remember their father,” she said. “They were too young. Mark turned 3 two days after Mike died. The first time I went to the Vietnam Wall, I saw people who were the ages of my children — late 20s — who were camped out there burning candles and crying. I didn’t want that for my children, and Mike wouldn’t have wanted that for his children.”

Allard is found

Allard remained a shadowy figure in everyone’s lives over the years since his death. Denny told her children about him and stayed in contact with Dave Allard and the rest of the family, and Mike occasionally popped into the memories of other friends.

Then, in January 1992, the Vietnamese government turned over to the United States the remains of what turned out to be 16 soldiers. In 1993, a team went and further excavated several sites, including an area where Allard’s plane went down.

Allard’s survivors were unaware that the remains included Mike’s bones until about four years ago, when the military’s Central Identification Lab in Hawaii called Dave Allard and his sister, Joan Gargas, and asked for samples of their blood.

Tom Holland, scientific director of the lab, said the blood was needed so that its DNA could be compared to DNA extracted from bones.

“Even under the best circumstances, getting DNA from bone is fraught with difficulties,” Holland said. “And in this case the bone was laying out in the jungle for 25 years and was in pretty bad shape.”

The Allards didn’t know how difficult it would be.

“It happened over the past four years,” Denny said. “They would ask for something, then you wouldn’t hear anything for 15 months. I really didn’t understand. I didn’t get the big picture until they came with the report. When they called to make the appointment last summer, I didn’t even know they had done the DNA testing.”

In October, a group from the lab visited Denny and gave her more details about her husband’s death. Holland had signed a report positively identifying the bones as Allard’s — one of 23 Marathon County residents killed in Vietnam.

“The military takes it very seriously because we have a commitment to the men we send into harm’s way,” Holland said. “We owe them the assurance that, when you leave to do your duty to this country, we will live up to our responsibility that we will bring you back to your family.”

Word quickly spread among Allard’s survivors and, eventually, to Mancer Cyr, a 58-year-old Wausau native who lives in New Jersey now. A few weeks ago, he learned that he had a friend who also was a friend of Mike’s older brother, Dave.

Cyr recalled Mike Allard as an older high school classmate who played football but didn’t remember much about him. When the friend told Cyr the story of Allard’s death, Cyr realized he and his wife had just made plans to be in Washington, D.C., at the time of Monday’s memorial service.

He decided to attend the memorial and e-mailed five old friends who he thought might remember Allard.

“I told people I was going to the funeral, and if anyone wanted to send letters I could take them to the family,” Cyr said. “And the letters just started pouring in. Then I got the idea to tell people at Marquette and sent a note to the alumni director. She sent the e-mail to a fraternity brother, and now there’s seven fraternity brothers coming to the service.”

At last count, Cyr figured about 100 people will be at the ceremony Monday, including Allard’s three boys. All will finally have a chance to say goodbye to the young man they knew — or never had a chance to know — 34 years ago.

“I just sort of thought this would be a small family funeral,” Denny said. “I’ve been very surprised by the response, but it’s a very nice surprise. The letters are very moving, and, for my children, this is a wonderful opportunity for them to have some true closure and meet people who knew their dad. I had my closure years ago, but I imagine Monday will be an emotional day for all of us.”

March 20, 2001:

ARLINGTON, Va. — Paul Allard says there was no doubt that his father died instantly when his A-4 Skyhawk bomber went down in combat over North Vietnam in 1967.

A wing man flying another A-4 bomber reported no sign of a white parachute when the Navy jet piloted by the Wausau High School graduate hit a rice paddy at full velocity.

“We didn’t dwell on his death all these years and went on with our own lives,” said Allard, a 35-year-old mechanical engineer who is married with two children and now lives in northwest Arkansas near his mother and two brothers.

It was in this context that U.S. Navy Lt. Mike Allard’s middle son reflected on the military pomp and ceremony that accompanied the Monday morning burial of his father’s remains at Arlington National Cemetery.

Long before four F-18 Hornet jets flew directly over Allard’s grave site in a “missing man” formation using data from a portable global positioning device held by an officer on the ground to find their mark, the family knew Mike Allard’s sacrifice was not forgotten.

Over the years, the family of the Navy pilot has been kept abreast of every development in the government’s investigation of his death. From an interview with a local farmer 15 years ago to bones turned over by the North Vietnamese government several years ago and a more recent archaeological dig, the family has been briefed repeatedly, Paul Allard said.

They have been shown photos of a large crater at the scene of the crash. A DNA specialist explained how positive identification of his bones was made.

“What a great country that they would go to the effort to find his remains,” Allard said.

The bone fragments gathered from these sources were buried Monday inside a Navy uniform placed in a silver casket with gold trim.

About 50 family and friends attended a memorial Mass celebrated by a Roman Catholic chaplain, Lt. Shaun Brown, at one of the cemetery’s two chapels.

Afterward, the flag-draped casket was placed on a caisson pulled by six white horses down a sloping road behind a 15-piece military band and an armed escort of two dozen sailors from the U.S. Navy Ceremonial Guard.

As the family stood at the graveside in section 66 and the pallbearers lifted the flag off the casket, a drum roll faded and the silence was broken by a 21-gun salute from a naval firing party armed with M-14s.

Moments later, the F-18s flew over on cue, with one pulling away as they approached to signify the missing pilot lost in action.

And as the nearby church bell tolled the 10 o’clock hour, the flag was folded and handed to the widow, Denise “Denny” Allard Higgens.

She described Monday’s ceremony as an opportunity for “wonderful closure for my sons,” who were all preschoolers when their father died.

The family chose Arlington National Cemetery over other possible cemeteries because of its national significance.

“People are so transient today and move around so much,” Allard Higgens said. “I don’t know where my kids will all be in 20 years, but we all thought this would be a place we would visit again.”

The pilot’s older brother, Dave Allard of Carmel, Calif., said the ceremony served as an opportunity for two of his children to meet some of their cousins for the first time.

“Not many of the family live in Wisconsin anymore, but some of the people here were Mike’s fraternity brothers at Marquette University,” Dave Allard said. “People have come from all over the country.”

For Paul Allard, this visit was his second to the Washington area.

In 1987 during a college break, he and older brother Mark visited the Vietnam Veterans Memorial directly across the Potomac River from the cemetery to find their father’s name on the black granite walls. They also visited their father’s commanding officer and drove to the Virginia Beach area where many Navy families live.

Rather than regret the past, Paul Allard celebrated how the family has progressed.

“We would be an example of the way the government works at its best,” said Allard, noting that his two brothers have become successful as an orthopedic surgeon and an accountant.

In the 10 years before their mother remarried, she continued to receive military health benefits for herself and her three sons as well as shopping privileges at a military commissary.

And the three boys all received partial financial aid for college.

“All this allowed us to succeed,” Paul Allard said.”

National Archives and Records Administration

Center for Electronic Records

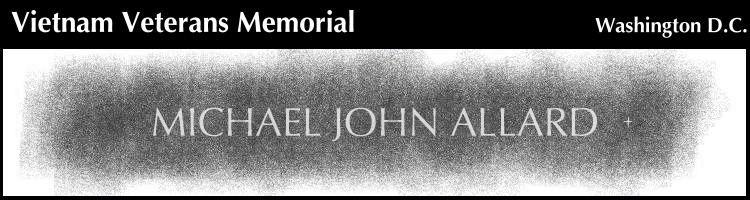

“MICHAEL JOHN ALLARD

Panel : 25E

Line 067

Navy

Lieutenant Fixed wing Pilot

Pay grade O3

Killed in action August 30, 1967 by Air loss – crash on land hostile, died in province or military region unknown North Vietnam. The body was not recovered. Home of record was SCHOFIELD, WI. Born September 12, 1940 age at death 26. A Caucasian Male, Married. Religous affiliation Roman Catholic.

CAACF Record Number : 657393

ALLARD, Michael John

Name: Michael John Allard

Rank/Branch: United States Navy/03

Unit:

Date of Birth: 12 September 1940

Home City of Record: Schofield WI

Date of Loss: 30 August 1967

Country of Loss: North Vietnam

Loss Coordinates: 183459 North 1054459 East

Status (in 1973): Killed in Action/Body not recovered

Category: 2

Aircraft/Vehicle/Ground: A4E

Missions:

Other Personnel in Incident:

Refno: 0819

Source: Compiled by P.O.W. NETWORK from one or more of the following: raw

data from U.S. Government agency sources, correspondence with POW/MIA

families, published sources, interviews and CACCF = Combined Action

Combat Casualty File.

REMARKS:

Pilot/Crashed”

March 21, 2002:

A 26-year-old Wausau native, U.S. Navy Lt. Mike Allard and his A-4 Skyhawk crashed into a jungle hillside just across the North Vietnam border.

That was 34 years ago.

Bones, all that’s left of Allard’s body, were buried at Arlington National Cemetery this week after DNA tests provided positive identification.

Attending the memorial service were the three sons who barely knew their father. Mark is 36, Paul, 35, and Bart, 34.

Also there were Allard’s widow, Denise (Denny) Allard Higgins, who is a school principal in Arkansas, and Wausau native Mancer Cyr, who attended Wausau Senior High School with Allard.

Through Cyr’s efforts, seven of Allard’s fraternity brothers from Marquette University — where Mike met Denny — were on hand.

The service for a man gone for 34 years drew about 100 people.

Gone. Not forgotten.

A 17-year-old Wausau girl has worn a bracelet inscribed with Allard’s name, one of the state’s missing in action, since seventh grade.

She picked it out because Allard’s plane went down on Aug. 30, 1967. And she was born in August. Now she intends to return it to Allard’s family.

Her hometown had 4,383 Asian residents when the 2000 Census was taken, so unlike the Wausau Allard left behind.

Most of the newcomers are Hmong-Americans, survivors of a horrific war and heroic escapes from Laos.

The CIA recruited the Hmong to serve in a secret war. Their orders included rescuing downed American pilots.

If Allard had crashed over Laos rather than North Vietnam, there’s a good chance his body would’ve been pinpointed and retrieved.

After the United States lost the war, the Hmong lost their homeland. Those who had fought on our side were killed like vermin, their bodies left to lay. As Allard’s had been>

The complete story of what happened on Aug. 30, 1967, the date memorialized on a schoolgirl’s bracelet and etched in Denny Allard Higgins’ mind, hasn’t yet been told. It’s still classified. We might never know.

This much is clear, however.

We are all — every one of us — woven into the same tapestry, strengthening the cloth of humankind.

Mike Allard died on a hillside in North Vietnam in August of 1967. The connecting threads — his wife, children, friends, people in Wausau who he would not live to know — go on.

In this web of life, anything that affects one of us, affects us all. For good or evil.

So it’s a comfort that one of the 23 Marathon County residents who died in Vietnam has been laid to rest, with his nation’s respect and honor properly bestowed.

At last.

Godspeed, Mike Allard.”

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard