From a contemporary press report

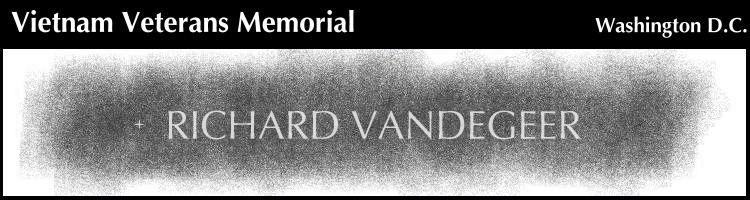

On October 27, 2000, Air Force helicopter pilot Second Lieutenant Richard Vandegeer — the last name on the Vietnam Memorial in Washington — will be buried in a solemn, private ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery, capping a decade-long recovery and identification operation by the Army Central Identification Laboratory, based in Honolulu.

The identification by the lab, known as CILHI, took four years and the use of “the most cutting-edge technologies available” to sort Vandegeer’s remains from those of the others killed in the crash that took his life, said John Byrd, a CILHI staff anthropologist. His work on the case included supervising archaeological digs on Koh Tang Island, Cambodia, where Vandegeer’s helicopter crashed on May 15, 1975, in the last combat action of the Vietnam War.

In fact, from the Global Positioning System-based receivers and laser transits used to locate the aircraft to the radio e-mail systems accessed by search teams in remote areas, technology was a big part of the recovery operation. And it will remain so, as the lab continues to handle search-and-identification operations for soldiers of the Vietnam and Korean wars, and even those of World War II.

“Any veteran would appreciate knowing that our country would care enough to come looking and remove us from a mudhole and bring what was left back home,” said Warner Britton, a retired Air Force pilot who flew helicopters similar to Vandegeer’s in Vietnam. “But more important, the program gives some hope to families who lost these men.”

Byrd said the seven water and land recovery operations on Koh Tang for remains from Vandegeer’s helicopter started in 1991 and yielded a large number of “commingled” remains. Besides Vandegeer’s remains, CILHI recovered what it believed to be remains from 10 Marine infantrymen and two Navy corpsmen from the 2nd Battalion, 9th Marine Regiment, on board Vandegeer’s helicopter, known as Knife 31.

The number of personnel involved in the crash, as well as the large number of bone fragments, “presented a challenge to the science. . .The more remains you have at a site, the difficulty goes up dramatically,” Byrd said. Six Marines have also since been identified, and identifications of the two Navy corpsmen are pending.

Privacy statutes preclude Byrd from discussing individuals, but sources outside the U.S. Department of Defense confirmed the identification of Vandegeer and his burial date.

The lab tapped into the smarts of a forensic computer program developed at the University of Tennessee, called ForDisc, which automates the process of matching skeletal remains, Byrd said. ForDisc is based on an extensive skeletal database that comprises samples of racial and body types found throughout the population, Byrd said, and allows scientists from CILHI to quickly determine the probability of whether a femur of a certain length matches a tibia of a certain length, for example. Recent new methodology extends that capability to bone fragments as well.

This is a key piece of software, because the CILHI scientists work “blind” when they begin analysis of skeletal remains, with no prior knowledge of the physical characteristics or even the number of individuals involved in an incident, according to a command briefing. It’s also more useful than DNA in cases where the number of individuals involved raises the possibility that the same base pair sequence will show up in more than one set of remains, Byrd said.

But ultimately, it is often dental records that affirmatively identify remains. “The anatomy of teeth, cavity patterns, restorations and extractions can lead to the identification of an individual,” much like fingerprints can, said Army Lt. Col. Cal Shiroma, a CILHI forensic odontologist.

CILHI maintains an extensive dental database, called the Computer Assisted Post Mortem Identification system, which contains the dental records of all U.S. personnel missing in Asia. Shiroma can scan in as many as 30 X rays of a recovered tooth and use the database’s search engine to generate candidates for a match. A computerized dental radiography system then fine-tunes that match, Shiroma said.

Vandegeer’s remains were first identified in 1995, and the process was completed last November. Independent authorities then spent nearly one year confirming those results, sources said.

CILHI’s computer and communications support is provided by Resource Consultants Inc. in Waipahu, Hawaii. The records of the missing servicemen from three wars, as well as data related to recovery operations such as maps, aerial photographs and scientists’ field notes, currently occupy 30GB of storage space, on-site consultant Gary Stephens said.

A gradual thaw in U.S. relations with North Korea has resulted in an increase in recovery missions in that country, said Stephens, and the command has started a crash imaging project to scan into a database literally millions of pages from the records of the Korean War MIAs, a project that in its infancy has already consumed 39GB of storage space.

“I believe what we do here is meaningful to the American people, especially the families [of the men missing in action],” Byrd said.

Courtesy of the Washington Post

From a Name on the Vietnam Wall to a Place at Arlington–Finally

By Steve Vogel

Washington Post Staff Writer

Thursday , November 2, 2000

The man behind the last name on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial has come home.

Air Force Second Lieutenant Richard Vandegeer, a member of the last group of Americans killed as part of the war in Southeast Asia, was buried Friday at Arlington National Cemetery. The last name listed on the memorial on the Mall, Vandegeer was killed off the coast of Cambodia in May 1975 during an operation to rescue crew members of a merchant ship that had been seized by the Khmer Rouge.

His parents, Paul and Diana Vandegeer, of Florida, were presented with American flags at the ceremony. An Air Force MH-53 Pave Low helicopter from the 20th Special Operations Squadron, based at Hurlburt Field in Florida, flew over in salute to the Air Force helicopter pilot.

The SS Mayaguez was captured by Khmer Rouge in gunboats on May 12, 1975, in the Gulf of Thailand off the coast of Cambodia and taken to Koh Tang, an island. Helicopters carrying Marines were dispatched May 15 to rescue the Mayaguez crew. Nearing the island, one of the CH-53 helicopters, piloted by Vandegeer, was hit by enemy antiaircraft fire and crashed into the surf with 26 men on board. Of those, 13 were rescued at sea.

Four or five of the men who were lost may have escaped the helicopter only to die in the surf or on shore, according to the Air Force. At least eight of the 13 probably died on the aircraft, the Air Force says, citing eyewitness accounts.

In 1995, U.S. and Cambodian authorities conducted an underwater search of the helicopter crash site and located numerous remains, personal effects and aircraft debris.

In May, the Pentagon released the names of four Marines whose remains had also been identified: Lance Corporal Gregory S. Copenhaver, of Port Deposit, Maryland.; Lance Corporal Andres Garcia, of Carlsbad, New Mexico; Private First Class Walter Boyd, of Norfolk, Virginia; and Private First Class Kelton R. Turner, of Los Angeles. The remains of Vandegeer were also identified, using DNA testing.

More than 1,900 service members from Vietnam remain missing in action.

Retired Lieutenant General Harry A. Goodall presents the flag to the family of Second Lieuenant Richard Van de Geer during a full honors funeral Oct. 27, at Arlington National Cemetery. Goodall was the wing commander at the time Van de Geer died in an aircraft accident on Ko Tang Island, Cambodia, during the USS Mayaquez Rescue May 15, 1975. Van de Geer was the pilot and only Air Force member killed on a CH-53 helicopter carrying 26 people. Thirteen people were rescued and 13 perished including 10 Marines and two Sailors. Van De Geer’s name is the last name inscribed on the Vietnam Memorial in Washington

Photos courtesy of the United States Air Force

Name: Richard Van de Geer

Rank/Branch: O1/US Air Force

Unit: 21st Special Operations Squadron – Nakhon Phanom, Thailand

Date of Birth: 11 January 1948

Home City of Record: Columbus OH

Date of Loss: 15 May 1975

Country of Loss: Cambodia/Over Water

Loss Coordinates: 101800N 1030830E (TS965400)

Status (in 1973): Killed/Body Not Recovered

Category: 3

Aircraft/Vehicle/Ground: CH53A

Refno: 2003

Source: Compiled from one or more of the following: raw data from U.S. Government agency sources, correspondence with POW/MIA families, published sources, interviews. Updated by the P.O.W. NETWORK in 1998.

Other Personnel in Incident: Daniel A. Benedett; Lynn Blessing; Walter Boyd; Gregory S. Copenhaver; Andres Garcia; Bernard Gause Jr., James J. Jacques; Ronald J. Manning; James R. Maxwell; Richard W. Rivenburgh; Antonio R. Sandoval; Kelton R. Turner (all missing on CH53A); Gary L. Hall; Joseph N. Hargrove; Danny G. Marshall (missing on Koah Tang Island); Ashton N. Loney (missing from Koah Tang Island); Elwood E. Rumbaugh (missing from a CH53A)

REMARKS: 750515 MAYAGUEZ INCIDENT LOSS

SYNOPSIS: When U.S. troops were pulled out of Southeast Asia in early 1975, Vietnamese communist troops began capturing one city after another, with Hue, Da Nang and Ban Me Thuot in March, Xuan Loc in April, and finally on April 30, Saigon. In Cambodia, communist Khmer Rouge had captured the capital city of Phnom Penh on April 17. The last Americans were evacuated from Saigon during “Option IV”, with U.S. Ambassador Martin departing on April 29. The war, according to President Ford, “was finished.”

2Lt. Richard Van de Geer, assigned to the 21st Special Ops Squadron at NKP, had participated in the evacuation of Saigon, where helicopter pilots were required to fly from the decks of the 7th Fleet carriers stationed some 500 miles offshore, fly over armed enemy-held territory, collect American and allied personnel and return to the carriers via the same hazardous route, heavily loaded with passengers. Van de Geer wrote to a friend, “We pulled out close to 2,000 people. We couldn’t pull out any more because it was beyond human endurance to go any more…”

At 11:21 a.m. on May 12, the U.S. merchant ship MAYAGUEZ was seized by the Khmer Rouge in the Gulf of Siam about 60 miles from the Cambodian coastline and eight miles from Poulo Wai island. The ship, owned by Sea-Land Corporation, was en route to Sattahip, Thailand from Hong Kong, carrying a non-arms cargo for military bases in Thailand.

Capt. Charles T. Miller, a veteran of more than 40 years at sea, was on the bridge. He had steered the ship within the boundaries of international waters, but the Cambodians had recently claimed territorial waters 90 miles from the coast of Cambodia. The thirty-nine seamen aboard were taken prisoner.

President Ford ordered the aircraft carrier USS CORAL SEA, the guided missile destroyer USS HENRY B. WILSON and the USS HOLT to the area of seizure. By night, a U.S. reconnaissance aircraft located the MAYAGUEZ at anchor off Poulo WaI island. Plans were made to rescue the crew. A battalion landing team of 1,100 Marines was ordered flown from bases in Okinawa and the Philippines to assemblE at Utapao, Thailand in preparation for the assault.

The first casualties of the effort to free the MAYAGUEZ are recorded on May 13 when a helicopter carrying Air Force security team personnel crashed en route to Utapao, killing all 23 aboard.

Early in the morning of May 13, the Mayaguez was ordered to head for Koh Tang island. Its crew was loaded aboard a Thai fishing boat and taken first to Koh Tang, then to the mainland city of Kompong Song, then to Rong San Lem island. U.S. intelligence had observed a cove with considerable activity on the island of Koh Tang, a small five-mile long island about 35 miles off the coast of Cambodia southwest of the city of Sihanoukville (Kampong Saom), and believed that some of the crew might be held there. They also knew of the Thai fishing boat, and had observed what appeared to be caucasians aboard it, but it could not be determined if some or all of the crew was aboard.

The USS HOLT was ordered to seize and secure the MAYAGUEZ, still anchored off Koh Tang. Marines were to land on the island and rescue any of the crew. Navy jets from the USS CORAL SEA were to make four strikes on military installments on the Cambodian mainland.

On May 15, the first wave of 179 Marines headed for the island aboard eight Air Force “Jolly Green Giant” helicopters. Three Air Force helicopters unloaded Marines from the 1st Battalion, 4th Marines onto the landing pad of the USS HOLT and then headed back to Utapao to pick up the second wave of Marines. Planes dropped tear gas on the MAYAGUEZ, and the USS HOLT pulled up along side the vessel and the Marines stormed aboard. The MAYAGUEZ was deserted.

Simultaneously, the Marines of the 2/9 were making their landings on two other areas of the island. The eastern landing zone was on the cove side where the Cambodian compound was located. The western landing zone was a narrow spit of beach about 500 feet behind the compound on the other side of the island. The Marines hoped to surround the compound.

As the first troops began to unload on both beaches, the Cambodians opened fire. On the western beach, one helicopter was hit and flew off crippled, to ditch in the ocean about 1 mile away. The pilot had just disembarked his passengers, and he was rescued at sea.

Meanwhile, the eastern landing zone had become a disaster. The first two helicopters landing were met by enemy fire. Ground commander, (now) Col. Randall W. Austin had been told to expect between 20 and 40 Khmer Rouge soldiers on the island. Instead, between 150 and 200 were encountered.

First, Lt. John Shramm’s helicopter tore apart and crashed into the surf after the rotor system was hit. All aboard made a dash for the tree line on the beach.

One CH53A helicopter was flown by U.S. Air Force Major Howard Corson and 2Lt. Richard Van de Geer and carrying 23 U.S. Marines and 2 U.S. Navy corpsmen, all from the 2nd Battalion, 9th Marines. As the helicopter approached the island, it was caught in a cross fire and hit by a rocket. The severely damaged helicopter crashed into the sea just off the coast of the island and exploded. To avoid enemy fire, survivors were forced to swim out to sea for rescue. Twelve aboard, including Maj. Corson, were rescued. Those missing from the helicopter were 2Lt. Richard Van de Geer, PFC Daniel A. Benedett, PFC Lynn Blessing, PFC Walter Boyd, Lcpl. Gregory S. Copenhaver, Lcpl. Andres Garcia, PFC James J. Jacques, PFC James R. Maxwell, PFC Richard W. Rivenburgh, PFC Antonio R. Sandoval, PFC Kelton R. Turner, all U.S. Marines. Also missing were HM1 Bernard Gause, Jr. and HM Ronald J. Manning, the two corpsmen.

Other helicopters were more successful in landing their passengers. One CH53A, however was not. SSgt. Elwood E. Rumbaugh’s aircraft was near the coastline when it was shot down. Rumbaugh is the only missing man from the aircraft. The passengers were safely extracted. (It is not known whether the passengers went down with the aircraft or whether they were rescued from the island.)

By midmorning, when the Cambodians on the mainland began receiving reports of the assault, they ordered the crew of the MAYAGUEZ on a Thai boat, and then left. The MAYAGUEZ crew was recovered by the USS WILSON before the second wave of Marines was deployed, but the second wave was ordered to attack anyway.

Late in the afternoon, the assault force had consolidated its position on the western landing zone and the eastern landing zone was evacuated at 6:00 p.m. By the end of the 14-hour operation, most of the Marines were extracted from the island safely, with 50 wounded. Lcpl. Ashton Loney had been killed by enemy fire, but his body could not be recovered.

Protecting the perimeter during the final evacuation was the machine gun squad of PFC Gary L. Hall, Lcpl. Joseph N. Hargrove and Pvt. Danny G. Marshall. They had run out of ammunition and were ordered to evacuate on the last helicopter. It was their last contact. Maj. McNemar and Maj. James H. Davis made a final sweep of the beach before boarding the helicopter and were unable to locate them. They were declared Missing in Action.

The eighteen men missing from the MAYAGUEZ incident are listed among the missing from the Vietnam war. Although authorities believe that there are perhaps hundreds of American prisoners still alive in Southeast Asia from the war, most are pessimistic about the fates of those captured by the Khmer Rouge.

In 1988, the communist government of Kampuchea (Cambodia) announced that it wished to return the remains of several dozen Americans to the United States. (In fact, the number was higher than the official number of Americans missing in Cambodia.) Because the U.S. does not officially recognize the Cambodian government, it has refused to respond directly to the Cambodians regarding the remains. Cambodia, wishing a direct acknowledgment from the U.S. Government, still holds the remains.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard