Born on February 25, 1888 he was a World War I veteran. He was appointed in the United States Senate from New York, serving out the term of Robert F. Wagner, who had retired due to ill-health. He was defeated for re-election.

He subsequently served as Secretary of State in the administration of President Dwight D. Eisenhower, where he was instrumental in forming the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO). He resigned his office on April 15, 1959 as a result of a bout with cancer. He was awarded the Medal of Freedom (America’s highest civilian award) shortly before his death on May 24, 1959.

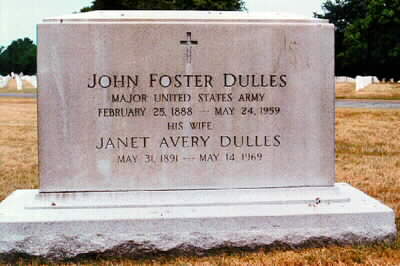

He is buried in Section 31 of Arlington National Cemetery. His wife, Janet Avery Dulles (May 31, 1891-May 14, 1969) is buried with him.

May 25, 1959

OBITUARY

Dulles Formulated and Conducted U.S. Foreign Policy for More Than Six Years

Tenure Aroused Mixed Appraisal

Admirers Hailed His Tactics in Diplomacy but Critics Scored Inflexibility

Cabinet In His Heritage

His Grandfather and Uncle Had Served the Nation as Secretaries of State

For six years John Foster Dulles dominated both the making and the conduct of United States foreign policy. In the realm of foreign affairs he was President Eisenhower’s chief adviser, his chief representative on Capitol Hill and his chief agent and negotiator at home and abroad.

Mr. Dulles was a highly controversial Secretary of State. Those who followed his career were rarely dispassionate; they divided, usually, between ardent admirers and those who disliked or distrusted him.

Certain things, however, were incontestable. First was the extent of his role. He was undoubtedly the strongest personality of the Eisenhower Cabinet, and as such he constantly played a leading role in Washington and often in the councils of the Western alliance.

Secondly, whatever his qualities as a policy-maker, he had few peers as an advocate. No one could equal him as a persuader in the White House councils. In facing the Senate Foreign Relations Committee he sometimes encountered criticism and skepticism, but he inevitably had his way.

Thirdly, he had extraordinary vitality. He maintained personal contacts and sought to exercise American leadership by constant travel in all parts of the world. As Secretary he flew a total of 479,286 miles outside the United States.

Successful Lawyer And a Moralist

Mr. Dulles was a man of complex character, full of paradoxes. A shrewd and successful corporation lawyer, he was also a moralist and political philosopher. He could marshal his ideas swiftly, fluently and extemporaneously; he coined many phrases, but he was not noted as an originator of new ideas.

He was gregarious, but he worked alone, to the despair of his State Department staff.

Gracious in private, he was often awkward in public, yet he held news conferences more regularly than any other member of President Eisenhower’s Cabinet.

Handsome as a young man, Mr. Dulles in later years assumed the characteristics of a stern church elder. When in repose the corners of his mouth drooped in an expression of extreme gravity that some observers have related to his strict Presbyterian upbringing. But this expression was relieved by frequent broad smiles.

His physique, as displayed on the occasions when he took time for a swim, was impressive. He was muscular, lean, with powerful shoulders, the result of much swimming, boating and fishing during boyhood.

This physical equipment made it possible for him to put in eleven-hour working days in Washington and then go on to his evening’s social obligations. It also enabled him, when traveling, to transform his airplane into an office, so that after a grueling flight he was ready for the conference table.

Cabin in Ontario Was His Retreat

Part of Mr. Dulles’ secret was his ability to relax. During negotiations he would be seen slumped in his chair, doodling or sharpening pencils, seemingly without a care in the world.

Mr. Dulles also knew the virtue of “getting away,” for five-day breaks at his log cabin retreat on Duck Island in Lake Ontario. In 1941 he bought this tiny island, where the only other inhabitants were a lighthouse warden and radio operator.

He and his wife Janet discovered and fell in love with it during their many summer sailing expeditions in the Great Lakes. They liked to withdraw to the privacy of their island and rough it, hauling water, chopping wood, fishing and cooking. Mr. Dulles took pride in his cooking, especially fish.

In Washington the Dulleses lived comfortably in a spacious stone house on a wooded hillside ten minutes from the State Department offices. This was their choice. Prosperous years as a corporation lawyer–the best paid in the history

of New York City, according to some accounts– had left him financially independent.

The Dulles family never suffered particularly for lack of money. John Watson Foster, Mr. Dulles’ grandfather, saw to that. Born in a log cabin in Indiana, he became a brigadier general in the Civil War, United States Minister to Mexico

and Russia and Secretary of State under President Benjamin Harrison. He amassed his fortune as a successful lawyer.

This grandfather, in whose Washington home he was born on Feb. 25, 1888, and who started him on his legal and diplomatic career, was the greatest formative influence in Mr. Dulles’ life.

Grandfather Foster, however, was only a part of an active and rich family life that produced two other notable personalities–one is Mr. Dulles’ younger brother, Allen W., director of the Central Intelligence Agency. The other, his younger sister, Eleanor, joined the State Department before her brother got there and is at present the officer in charge of Berlin in the Office of German Affairs.

The Dulles family says it can trace its ancestry to Charlemagne. That it does not take this too seriously, however, is indicated by the fact that Mrs. Dulles named her French poodle “Pepi” after Pepin Le Bref, Charlemagne’s father.

Mr. Dulles’ father was the Rev. Allen Macy Dulles, pastor of the First Presbyterian Church at Watertown, N. Y. A liberal clergyman, he questioned whether belief in the Virgin Birth was essential to being a Christian, and he married divorced persons. Of his children he required rigorous and intensive religious life involving attendance at church three or four times a week and memorization of long passages from the Bible.

Enjoyed Swimming, Fishing and Sailing

Much of this stayed with Mr. Dulles throughout his life. He was always ready with a quotation from two books, and kept them within reach at home and at the office: the Bible and the Federalist. They represented, respectively, the religious influence of his father and the political influence of his grandfather.

Over the dinner table the Dulles children heard talk of morality and diplomacy. Sometimes “Uncle Bert”–Robert Lansing, later Secretary of State under President Woodrow Wilson–was there. Grandfather Foster would argue the case for the Boers and Uncle Bert the case for the British in the Boer War.

The family was fond of boating. When Foster was 13, after a bad case of typhoid fever, his grandfather presented him a twelve-foot St. Lawrence cat boat. From then on sailing, fishing and swimming were his greatest pleasures. For the rest of his life, in all kinds of weather, he took every opportunity to cruise Lake Ontario, the St. Lawrence, the coasts of Nova Scotia, Maine and Long Island.

The Rev. Mr. Dulles had a private income to supplement his pastor’s stipend, so the family could afford some summers in Europe. These were spent at Left Bank hotels in Paris and bicycling through the Lowlands and Germany. John Foster Dulles learned good French, some German and passable Spanish.

After grammar school and high school at Watertown, Foster went to Princeton University. At that time he expected to follow his father into the ministry and concentrated on the study of philosophy.

But an invitation to accompany Grandfather Foster, in the summer of 1907, to the second Hague Peace Conference, began to turn his interests toward diplomacy. Foster was then 19. His grandfather, who acted as delegate for the Imperial Government of China, got him a job as a secretary to the Chinese delegation on the strength of his knowledge of French.

Foster was graduated from Princeton in 1908 as valedictorian of his class, with a Phi Beta Kappa key and a $600 scholarship for a year’s study at the Sorbonne in Paris. By the end of that year he had made up his mind to study law rather than theology.

To be able to live with his grandfather, he decided to study at George Washington University in Washington. Through his grandfather he was drawn into a gay social life, but managed at the same time to absorb three years of law studies in two years with the highest grades ever achieved at the university.

Received Law Degree 25 Years Late

Because he had been in attendance only two years instead of three, the university declined to give him a degree. (It did so twenty-five years later.) But the young Mr. Dulles passed the New York State bar examinations and moved on to New York City in search of a job.

To his chagrin, he discovered that the big law firms on whose doors he knocked were not interested in graduates from George Washington University, much less one who had not even received a degree. Harvard and Columbia Law School, it seemed, were the “right” places to study law. It took a letter from Grandfather Foster to William Nelson Cromwell, senior partner of the firm of Sullivan & Cromwell, to win the young man a chance to start–at $50 a month.

On June 26, 1912, he and Janet Avery, of Auburn, N.Y., were married at Auburn. He then had a salary of $100 a month, but Grandfather Foster made it possible for the newlyweds to live fairly comfortably.

The income of Foster Dulles, the young lawyer, grew steadily as he distinguished himself in assignment after assignment, usually in the international field.

Rejected for military service during World war I because of poor eyesight, Mr. Dulles got an Army commission as captain in the War Industries Board. This, in turn, led to his being sent to the Versailles Peace Conference to deal

with reparations questions.

At the age of 31 Mr. Dulles made a preliminary mark as a junior diplomat by clearly and forcefully arguing against imposing crushing reparations on Germany.

President Wilson wrote a personal letter asking him to stay on in Europe after the conference to handle reparations questions. The fact that he was one of five men–another was Thomas W. Lamont, a partner in J. P. Morgan–who served as the President’s economic advisers at Versailles gave John Foster Dulles’ career another lift.

He became a partner in Sullivan & Cromwell with a substantially enhanced income. One international assignment followed another–to Norway, Denmark, Poland, Uruguay, Chile and other lands. Usually Mrs. Dulles accompanied him on his trips abroad.

In 1937 Mr. Dulles tried to hire as a trial lawyer for his firm a young man named Thomas E. Dewey who was winning a reputation as prosecutor of underworld characters. Mr. Dewey agreed, but changed his mind and ran instead for election as district attorney.

Thus began a long political association between Mr. Dulles and Mr. Dewey. In 1939 Mr. Dulles joined George Z. Medalie, a Republican lawyer, and Roger W. Straus, chairman of American Smelting and Refining Company, in planning Mr. Dewey’s strategy in seeking the Presidential nomination. Mr. Dewy lost to Wendell L. Willkie in 1940, but in 1944 he won the nomination and John Foster Dulles stepped in as his foreign policy adviser.

In this capacity Mr. Dulles was maneuvered into a conference with Cordell Hull, then Secretary of State, on the formation of the United Nations. This led to a bipartisan approach to the United Nations issue and to the appointment of Mr. Dulles as a senior United States adviser at the San Francisco conference of the United Nations in 1945.

Mr. Dulles’ stature in international affairs was established by his work at the San Francisco conference.

Mr. Dewey again sought the Presidency in 1948 and Mr. Dulles was again his advisor on foreign affairs. It was generally believed that Mr. Dulles would have been Secretary of State if Mr. Dewey had won, but Harry S. Truman was the surprise victor.

Mr. Dulles was a member of the United States delegation to the United Nations General Assembly in Paris in November, 1948, when Secretary of State George C. Marshall was forced to return to the United States for surgery. President Truman named Mr. Dulles acting chairman of the delegation.

He was with Secretary of State Dean Acheson at the Big Four foreign ministers’ conference in Paris in 1949. On July 7 of that year Governor Dewey named him to the United States Senate in an interim appointment to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of Senator Robert F. Wagner.

Campaigning on a platform critical of the Fair Deal of President Truman, Mr. Dulles sought election to the Senate in a special election in November, 1949. His opponent was former Gov. Herbert H. Lehman. Mr. Dulles was defeated by 196,293 votes–2,573,934 to 2,377,641.

In April, 1951, when President Truman removed General of the Army Douglas MacArthur from his Far East commands during the Korean fighting, Mr. Truman sent Mr. Dulles to Tokyo to assure the Japanese Government that General MacArthur’s departure signified no important change in United States policy in the Far East.

That there should be no misunderstanding on this point was of special importance to Mr. Dulles, who was engaged on his last and biggest job for President Truman–concluding a peace treaty with Japan.

This was a task that Mr. Dulles had sought. He had urged Secretary Acheson that the only way to get the long-delayed treaty was to pick one trusted man and give him a year, full-time, to work it out. Mr. Dulles got the job.

Treaty With Japan Was His Handiwork

During the next twelve months, he flew 125,000 miles between Washington and Tokyo and from capital to capital, resolving differences, lining up support for a “peace of reconciliation” with Japan.

On Sept. 8, 1951, just a year after Mr. Dulles got his assignment, the treaty was signed at San Francisco. Surveying Mr. Dulles’ handiwork, State Department officials admiringly paid tribute to a “master craftsman.”

During the Presidential campaign of 1952 Mr. Dulles forgot bipartisanship. The vitriolic assault on Democratic foreign policy he wrote for the Republican party platform caused critics to tax him for the first time–but not the last–with acting more like a corporation lawyer serving his client than a statesman.

After the election, Mr. Dulles was one of the first men President Eisenhower named to his Cabinet.

The job of Secretary of State was one that he apparently had been after for a long time. Certainly he had had it in mind when he involved himself in the Presidential campaigns of 1940, 1944 and 1948. But when he had it in his grasp he was said to have had doubts.

He realized that what he wanted was the foreign-policy function, and that as Secretary of State he would be burdened with many other tasks as well. He is said to have remarked that what he would really have liked was a quiet office in the White House as foreign-policy consultant, far from the cumbersome machinery of the State Department.

Yet there was never any question about Mr. Dulles’ conviction that he, with experience in foreign affairs dating to the Hague Conference of 1907, with a rich family background of diplomacy, was the man best qualified to call the turns of United States foreign policy.

He had it all in his head. He did not need the ambassadorial analyses and the studies of the policy planning staff and the host of departmental experts. He had a big yellow pad at his bedside and he jotted down thoughts as they occurred to him.

Thus were born the phrases around which United States foreign policy revolved for nearly seven years.

For example, during his campaign speeches in 1952, Mr. Dulles maintained that the Democratic party’s policy of “containment” must be replaced by a policy of “liberation.” What United States foreign policy needed, he said, was more “heart.”

President Eisenhower put these thoughts into practice by withdrawing the Seventh Fleet from the Formosa Strait, thereby “unleashing” President Chiang Kai-shek of Nationalist China for action against the mainland. For a time undercover operations in the Far East and in Eastern Europe were somewhat stimulated.

But when the tests came, in the anti-Communist Berlin riots in 1953, the French call for help at Dienbienphu in 1954, the Chinese Communist threat to Quemoy in 1954-55, the Hungarian rising against the Russians in 1956, the United States did not act. As things worked out, there was a wide margin between Mr. Dulles’ bold words and the United States Government’s actions.

Although Mr. Dulles never specifically confirmed it, there is good reason to believe that during the month of July, 1954, he and Admiral Arthur H. Radford twice tried to get the British to agree to a United States air strike, with planes based on carriers and in the Philippines, against the Communist forces attacking Dienbienphu, a key French stronghold in the north of Indochina.

But the British would not go along, as Mr. Dulles might have expected. The plan was abandoned, and Dienbienphu was lost.

SEATO Filled Gap In Asian Defense

In public Mr. Dulles spoke only of the need for “united action” by the Western Allies and their friends in Asia to oppose the Communists. And this in the end led to the formation of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization at Manila on Sept. 8, 1954.

Embracing Pakistan, Thailand and the Philippines in addition to the United States, Britain, France, Australia and New Zealand, SEATO went far toward closing the gaps in the world-wide network of military alliances, gaps that were a constant subject of concern to Mr. Dulles.

The philosophy behind Mr. Dulles’ maneuverings concerning Dienbienphu and other crises was spelled out in an article that he apparently inspired in Life magazine on Jan. 16, 1956.

It contained the definition of what some have called “brinkmanship”: “The ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is the necessary art.”

And he explained that his skill in doing just that had ended the Korean war (with an implied threat to drop atomic bombs on Manchuria), had restrained the Communist Chinese from sending their forces into Indochina (with a show of force by two aircraft carriers and an invitation to Allied nations to form a “united front”) and had headed off Communist invasion of Quemoy (with the bipartisan Formosa resolution authorizing armed United States intervention).

An important part of Mr. Dulles’ “brinkmanship” was “massive retaliation,” the boldest of all his phrases. He said in a speech on Jan. 12, 1954, that the President and National Security Council had decided “to depend primarily upon a great capacity to retaliate instantly, by means and at places of our own choosing.”

The storm aroused by these words obliged Mr. Dulles to explain later that of course the punishment must always suit the crime, that he was not talking about indiscriminate bombing of Moscow.

There were some other phrases that symbolized his tenure.

Addressing State Department employes on his first day in office, Mr. Dulles called for “positive loyalty.” He also said on another occasion:

“I’m not going to be caught with another Alger Hiss on my hands.”

As result of this attitude he tolerated for several years the operations of Walter Scott McLeod, a former agent of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and later a member of the staff of Styles Bridges, Republican Senator from New Hampshire. Mr. Dulles’ administrative Under Secretary hired Mr. McLeod as security chief.

When the cases of Jon Carter Vincent and John Paton Davies, State Department career men, came up for review, Mr. Dulles found nothing in their records showing lack of loyalty. But he retired them anyway, on the ground that they had become burdensome and that a Secretary of State could not afford to carry excess baggage.

Under this doctrine no Foreign Service officer could be sure that, if he were falsely accused of disloyalty, he would be backed up by his boss.

‘Reappraisal’ Talk Distressed French

Still another phrase was born on Dec. 14, 1953, when Mr. Dulles said in Paris that if the French Assembly did not approve the European Defense Community treaty “that would compel an agonizing reappraisal” of basic United States foreign policy.

The surprising thing about this statement was that after spending so many months in France Mr. Dulles did not realize that among sensitive Frenchmen his words would boomerang, and almost guaranteed the defeat of the defense community.

Mr. Dulles flew to Caracas, Venezuela on March 28, 1954, for a Pan American conference. He was largely responsible for the adoption of an anti-Communist resolution by which American Republics pledged “countermeasures” to prevent Communist control of any American state.

Getting the resolution adopted was a victory of a kind for Mr. Dulles, but many of the Latin Americans resented the pressure brought by the United States on behalf of the resolution.

The phrase “open skies”–mutual freedom to engage in aerial inspection–was not coined by Mr. Dulles. However, Mr. Dulles picked up the “open skies” proposal that President Eisenhower made to the Russians at the summit conference of 1955 and used it to underline the essentiality of mutual inspection during long and inconclusive negotiations on all aspects of disarmament. Always the talks broke down on the inspection issue.

At Iowa State College on June 9, 1955 Mr. Dulles said “neutrality has increasingly become an obsolete and except under very exceptional circumstances, it is an immoral and shortsighted conception.”

India and many other nations with neutralist tendencies in the Afro-Asian world took this as a gratuitous affront. Later Mr. Dulles conceded that neutrals of the immoral kind were “very few” in number. And toward the end of his period in office he acquired a growing appreciation of the value of genuine neutrality.

Indians were also offended by an illusion to “Portuguese provinces in the Far east,” meaning Goa, a Portuguese-owned territory on the coast of India. Mr. Dulles permitted the phrase to appear in a joint statement with Portugal’s Minister of Foreign Affairs on Dec. 2, 1955.

Mr. Dulles considered himself an expert on the Soviet Union. More often than on other topics he would make declarations about the Soviet without consulting his State Department aides.

Particularly striking, and particularly criticized, were his assertions of Soviet weakness. On Feb. 24, 1956, he told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that “at this moment in Moscow they are having to revise their whole program. They have failed.”

Mr. Dulles felt at home talking about Europe and the Soviet Union, but he was much less at ease when dealing with the Middle East. It is possible, nonetheless, that the concept of a “northern tier of defense” against the Soviet Union in the Middle East may have been his most original single contribution to foreign policy.

Originally intended as an association of the nations in the area, which the great powers would back but not join, the concept was radically changed by the British, who encouraged and joined the “Baghdad Pact.”

Still another foreign-policy concept, the Eisenhower Doctrine, proclaimed by both houses of Congress on March 9, 1957, was really the Dulles Doctrine. Mr. Dulles conceived and defended this resolution before Congress, asserting that the President was prepared to use armed force to support any Middle Eastern country that asked for help against Communist aggression.

Conceived Doctrine For the Mideast

Mr. Dulles did not succeed in preserving the momentary goodwill of the Arabs that had been generated by United States opposition to British-French-Israeli operations against Egypt in the fall of 1956. By the spring of 1958 the United States found itself sharply opposed to President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s penetration of Lebanon. Once again Mr. Dulles had a phrase for it: “indirect aggression.”

When revolution flared in Iraq in 1958 Mr. Dulles countered “indirect aggression” by the United Arab Republic with landings by United States forces in Lebanon.

Mr. Dulles will be remembered for his part in leading the Republican party out of its long tradition of isolationism into a new era of internationalism. Often criticized during his tenure for seeming inflexibility in his dealings with the Soviet Union, there was growing appreciation during his last months in office that his line was basically sound.

He achieved his objectives best in Europe, in spite of the rebuff he suffered on the issue of the European Defense Community. With Mr. Dulles’ encouragement West Germany regained sovereignty as a member of the North Atlantic alliance while at the same time progressively closing economic ranks with France.

In the Far East he stood inflexibly attached to alliance with Nationalist China and opposed to recognition of Communist China. With United States help, President Chiang Kai-shek was able to hold the islands of Quemoy and Matsu in spite of heavy Communist bombardment.

Chiang Reinforced Offshore Islands

Disregarding Mr. Dulles’ advice, Chiang retained the heavy manpower commitment to these islands through which, in another crisis, the United States could be drawn into war.

In the Middle East he lost heavily. By not making it possible for Egypt to acquire arms in the United States he opened the way for a Soviet-Egyptian arms deal that carried Soviet influence into the heart of the Middle East.

By dramatically withdrawing United States support for the Aswan high dam in Egypt he provoked President Nasser’s seizure of the Suez Canal Company, which led to an abortive British-French invasion of the Canal Zone and further deterioration of Western prestige.

By sending troops into Lebanon on the heels of the Iraqi revolution, he convinced the Iraqi revolutionaries that the United States might oppose them by force. They turned to the Soviet Union for help.

Mr. Dulles’ personal skill as a negotiator made him look almost indispensable. Time after time he mixed the diplomatic glue with which differences among the allies were papered over.

Mr. Dulles believed that to spend too much time in Washington would be to neglect his higher duties as leader in the Western alliance. Nevertheless his absences led to neglect of his administrative tasks and made it impossible for him to make full use of the State Department and the Foreign Service as diplomatic tools.

After the crisis on the European Defense Community the French called him brutal. After the Suez crisis the British accused him of double-dealing. After his remarks on Goa and neutrality the Indians tended to write him off.

But when Mr. Dulles had to withdraw from the international scene one word was heard over and over among the diplomats of Europe and Asia: “Indispensable.”

When President Eisenhower announced Mr. Dulles’ resignation he had tears in his eyes. The moment was so moving that no one could bring himself to ask a question. With mixed pity and consternation some remembered a remark attributed to the President several years ago:

“If anything happened to Foster, where could I find a man able to replace him?”

John Foster Dulles

Time Magazine’s 1954 Man of the Year

In an icy conference room in West Berlin one day last February, Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov sang an old, sour song. After nine years of delay and diatribe, the Soviet Union still refused to sign a peace treaty ending the occupation of Austria. As Molotov droned on, a tall man slouched low in a chair, whittling on a pencil, calmly watching the shavings drop to the floor. When the Russian had finished, John Foster Dulles blew the dust from his pocketknife, snapped it shut and shoved it into his pocket. Then the U.S. Secretary of State leaned forward.

“For about 2,000 years now,” said Dulles, “there has been a figure in mythology which symbolizes tragic futility. That was Sisyphus, who, according to the Greek story, was given the task of rolling a great stone up to the top of a hill. Each time when, after great struggle and sweating, the stone was just at the brow of the hill, some evil force manifested itself and pushed the stone down. So poor Sisyphus had to start his task over again. I suspect that for the next 2,000 years the story of Sisyphus will be forgotten, when generation after generation is told the tragic story of the Austrian state treaty. We have repeatedly been almost at the point of concluding an Austrian treaty, and always some evil force manifests itself and pushes the treaty back again.”

Then John Foster Dulles looked squarely at the man he had labeled the instrument of an evil force and said: “I think that the Soviet Foreign Minister will understand that it is at least excusable if we think, and if much of the world will think, that what is actually under way here is another illustration of the unwillingness of the Soviet Union actually to restore genuine freedom and independence in any area where it has once gotten its grip.”

War Against Gullibility. The Berlin Conference might have marked the beginning of calamity for John Foster Dulles–and for the people and the cause he represented. Instead, it was at Berlin that Dulles started on the way to become 1954’s Man of the Year. It was the first time in nearly five years that the foreign ministers of the Big Four had conferred. Much of the world was being lulled by new and gentle tones from Moscow. Did Malenkov’s Russia really want peace? In trying to get an answer that all the world would understand, Secretary of State Dulles at Berlin pressed Molotov with greater skill and force than any U.S. diplomat had ever shown in dealing with the Communists. With one sharp stroke after another, he stripped the Communists naked of the pretense that they really wanted peace at anything less than their own outrageous price. If millions remained deluded by the “soft” Malenkov line, that was not the fault of Dulles, who rescued other millions from gullibility.

Everywhere, and especially in Europe, gullibility was nurtured by the fear that no power could stop the Communists, that the only alternatives were an appeasing coexistence or an atomic world war in which the dreadful best outcome would be liberation after U.S. “massive retaliation” against Red aggression. Neither at Berlin last February nor throughout the year did Dulles try to veil the free world’s grim dependence on massive atomic retaliation. But he knew this to be a position of desperation, one that could not be held indefinitely unless the non-Communist world regained freedom of action, unless it found other than ultimate and apocalyptic ways to gather and use its strength.

In pursuit of such ways, Dulles spent 1954 in a ceaseless round of travel, logging 101,521 miles on journeys to Berlin, London, Paris, Caracas, Bonn, Geneva, Milan, Manila and Tokyo. In one fortnight last September, he munched mangoes with Philippines President Ramon Magsaysay in Manila, conferred with Chiang Kai-shek on Formosa, visited Premier Yoshida in Tokyo, reported to President Eisenhower in Denver, consulted with Winston Churchill in London and talked with Konrad Adenauer in Bonn. En route, he read a detective story in mid-Pacific, slept soundly across the Atlantic, and carried on U.S. State Department business as he crossed one international border after another.

On his trips to reinforce the free world outposts, Dulles sometimes merely shored up a wall that the Reds had breached, but on other sorties he served his primary mission: to develop the cohesion and strength that would make Communist aggression less likely and would, therefore, make the free world less directly dependent on massive retaliation, the defense it feared.

A Giant Stride. As the year ended, Dulles, back from his eighth transatlantic trip in twelve months, was able to report to the U.S. that plans for Europe’s defense had entered a new phase. Tactical atomic weapons (e.g., atomic howitzers and small rockets) now make it possible to halt a Red army ground attack: “The aggressor would be thrown back at the threshold” of Western Europe. The 14 NATO nations that discussed this with Dulles are agreed on how this threshold defense shall be coordinated. Said Dulles: “Thus we see the means of achieving what the people of Western Europe have long sought–that is, a form of security which, while having as its first objective the preservation of peace, would also be adequate for defense and which would not put Western Europe in a position of having to be liberated.”

John Foster Dulles played the key role in the NATO Council’s agreement on how to coordinate this giant stride. When Dulles got to Paris for the council meeting last fortnight, he found that both Anthony Eden and Pierre Mendes-France had prepared strict plans calling for consultation by the allies before nuclear weapons could be used. After dinner with Eden, Dulles pulled out his omnipresent yellow scratch-pad, scribbled out his own resolution. Next day both Eden and Mendes-France dropped their proposals, and the council adopted the Dulles plan within 30 minutes. It provided for consultation prior to use of nuclear weapons by NATO forces, but it did not set rigid rules or tie the hand of such non-NATO forces as the U.S. Strategic Air Command.

A Year of Shadowed Joy. In Dulles’ patient year of work and travel, every task and every mile was made harder by the mood of 1954, a year in which temptations to complacency and reasons for anxiety both mounted. For complacency, 1954 was superficially like the peaceful and prosperous ’20s. Between Sept. 18, 1931, when the Japanese moved into Manchuria, and Aug. 10, 1954, when the Indo-China fighting stopped, there was no day of worldwide peace. Between Oct. 24, 1929, when the stock market crashed, and 1954, there had been some years of boom, but it took 1954’s mild, controlled U.S. recession to bring home the solidity of the economic advance. The rest of the world had long feared the magnified effect of even a mild U.S. recession. But in 1954 business forged ahead in Britain, West Germany and many another country, despite the brief U.S. downswing. As U.S. indexes turned upward at year’s end, the 25-year-old belief that the world was tied to a boom-or-bust economy began to bust.

The result, as 1954 ended, was a feeling of firm confidence in the U.S. economy and in dynamic capitalism as an economic way of life. Secretary of the Treasury George Humphrey, a hard man with a dollar’s worth of optimism, summed up this economic feeling in a financial man’s superlative. Said he: “I’m a bull on the world.”

The main differences between the peace and prosperity of 1954 and of the ’20s were: I) 1954’s peace and prosperity had, in reality, far better prospects; 2) the 1920s’ feeling of confidence, which proved illusory, was much higher. Americans of 1954 knew that the technical peace was not real, that they had to keep almost 3,000,000 men under arms, maintain a peacetime conscription and spend an average of $855 a family for defense. The year that saw the hydrogen explosion at Bikini–the biggest explosion in man’s explosive history–was not one to foster illusions about an indefinite peace.

Yards Gained. The U.S. needed all its strength and confidence to handle 1954’s struggle with Communism, which has been the overriding issue of every year since 1945. Dulles both drew upon and nourished U.S. confidence in its national strength. Far from offending allies, the emphasis on U.S. interests had a wholesome effect of stimulating the national prides of other Western nations in a war that made them more self-reliant and more reliable partners in the struggle against the common enemy.

Dulles is the man of 1954 because, in the decisive areas of international politics he played the year’s most effective role. He made mistakes, and he suffered heavy losses. But he was nimble in disentangling himself from his errors. The heavier losses of 1954 were prepared by serious mistakes made years ago; Dulles limited the damage.

Regionally, 1954’s greatest area of success for American diplomacy and the man who runs it was the Middle East. There, a number of old problems were solved by new approaches. Items:

— After decades of dispute, the status of the Suez Canal area was settled more firmly than ever before. On the surface this was an affair between the British who agreed to withdraw their troops, are Egypt’s Man of the Year, Premier Gamal-Abdel Nasser. In fact, the settlement was skillfully midwifed by the U.S. State Department through Old Diplomat Jefferson Caffery, then Ambassador to Egypt.

— After three years of shutdown and stalemate at Abadan (caused by the stubborn egotism of 1951’s Man of the Year Mohammed Mossadegh), Iran agreed to let foreign firms (chiefly British) resume operating the Iranian oil industry, which the Iranians were incapable of operating. The agreement was prodded, adjusted and pushed through by Loy Henderson, the U.S. Ambassador to Iran, and Special U.S. Emissary Herbert Hoover Jr., now Under Secretary of State.

— After long and careful negotiation by U.S. diplomats, Turkey and Pakistan signed a military collaboration treaty. This was a key step toward Dulles’ goal of a “Northern Tier” defense against Soviet expansion.

In Europe and in the Americas, too there were some clear-cut gains. Items:

— At Caracas, in March, Secretary Dulles personally pushed through an inter-American resolution calling for joint action against Communist aggression or subversion. Said Dulles: “It may serve the needs of our time as effectively as the Monroe doctrine served the needs of our nation during the last century.” Only three months after Caracas, Jacobo Arbenz’ Communist-dominated government of Guatemala, the only Red bastion in the western hemisphere, was overthrown by the anti-Communist forces of Castillo Armas.

— The status of Trieste was settled after nine years of Communist-comforting tension between Italy and Yugoslavia. When U.S. Ambassador Clare Boothe Luce impressed Washington with the urgency of the settlement, U.S. and British diplomacy went to work. The Italians and the Yugoslavs were persuaded to sign a settlement dividing the territory, with the Italians getting the Italian city.

Holes Plugged. Dulles’ job includes defense as well as advance. He played goalkeeper in the free world’s two major setbacks of 1954: the death of the European Defense Community (to which he had said there was “no alternative”) and the defeat in Indo-China. Both setbacks stemmed from a single mistake made a decade ago, and never corrected in spite of mounting evidence. The mistake: that the victory of France’s allies over Germany somehow meant that France had recovered from the basic political weakness that caused its collapse in 1940. The postwar phrase–the Big Four–was a misnomer; France is not a great power, but a great civilization, politically paralyzed. EDC asked France to show a self-confidence it did not posses. Indo-China asked France to show a will to win it did not possess. A new Premier, Pierre Mendes-France, made France’s allies face the old fact of France’s weakness.

At the end of 1953, John Foster Dulles had said, quite pointedly, that the U.S. would be forced to make an “agonizing reappraisal” of its relations with France, of its policy toward Europe if EDC failed of ratification. (That expression and Dulles’ “massive retaliation” became the cold-war phrases of 1954.) A smaller man than Dulles might have insisted on a reappraisal immediately after Mendes-France presided over the French assassination of EDC. But Dulles swallowed his pride and helped the West lay the foundation for a substitute.

The substitute, to rearm and grant sovereignty to West Germany under a different set of agreements, was conceived by Britain’s Foreign Minister Anthony Eden one morning in his bathtub. Last October in Paris, with the help of Dulles and of West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer (the Man of 1953), Eden got his alternative plan approved at the foreign-minister level. Many military men discovered that they liked Eden’s Western European Union, with its appeal to nationalism, better than EDC, with its emphasis on European political unity. The Communists testified to the plan’s potential: they fought as desperately against it as they had against EDC.

The disaster in Indo-China left no doubt that three Communists were the Men of the Year in Asia. The victory belonged to Communist China’s Premier Mao Tse-tung, his Foreign Minister Chou En-lai, and to Ho Chi Minh, the leader of the Viet Minh. For a considerable measure of recovery from the Indo-China disaster, the free world could thank John Foster Dulles. First Dulles hammered out and pushed through the Manila Pact, which committed eight nations to take joint action against subversion and aggression in Asia.

More important, perhaps, was Dulles’ other Asian treaty of the year, the mutual defense agreement between the U.S. and Nationalist Chinese Leader Chiang Kai-shek. One tribute to the treaty’s impact was the angry reaction of the Communist Chinese. The pact did not establish any new principle, but it wiped out some doubts. Said Dulles: “It is my hope that the signing of this defense treaty will put to rest once and for all rumors and reports that the U.S. will in any manner agree to the abandonment of Formosa and the Pescadores to Communist control.”

Despite these attempts to shore up the anti-Communist position, the free world came to year’s end with a net loss and a troubled outlook in Asia. There was scant hope that the Communists could be prevented from swallowing up all of Viet Nam. There was great danger in the aura of success that surrounded the Communists in the Far East, where the people want to know: Which side will win? Even in Japan, where the West’s good friend, Premier Yoshida, was forced to resign, there was new talk of trade and friendship with Red China. On 1954’s Asian ledger, the big figures were all Red.

He Likes the Work. As the Man of 1954 went through his incredibly difficult year, he was sustained by an important basic attitude: he likes the work. President Eisenhower and most members of his Cabinet can truthfully say that they did not dream of holding the jobs they have, and took them only out of sense of duty. But John Foster Dulles has wanted, almost all his life, the job he now holds. He learned his first lessons in international relations at the knee of his maternal grandfather, John Foster, who was Secretary of State in Benjamin Harrison’s Cabinet and who helped negotiate the 1895 treaty that ended the Sino-Japanese War. At 19, he was secretary of China’s delegation at the Second Hague Peace Conference; at 30, he served on the Reparations Commission at Versailles. Between the wars he had a brilliant legal career. In 1941 he got the Federal Council of Churches to set up a Commission to Study the Bases of a Just and Durable Peace, headed it, and wrote a report that applied Christian principles to historical realities.

Called in by the Truman Administration after the end of World War II, Dulles negotiated a peace treaty with Japan that was the soundest bit of diplomacy that he inherited when he became Secretary of State in 1953. The rest of his policy inheritance was jerry-built on emergency and crisis. Dulles’ first aim was to build a foreign policy for the long haul. To replace fear as the glue of the free world’s alliances, he said he wanted to develop a cement compounded of strength, understanding and cooperation. He has explained the difficulty of this operation: “The best insurance against war is to be ready, able and willing to fight. Now it is extremely difficult to hold that position without leading some of our friends and allies to think that we are truculent and want to have a fight.”

Ducking the One-Two. Because Presbyterian Dulles (a clergyman’s son) talked a great deal about moral principle, some feared that he was trying to force his Christian morals on the rest of the world. But he has demonstrated that a diplomat who is clear about his own principles can find them highly useful in practical international politics.

By the end of 1954. Dulles, who had been accused of saber rattling with such phrases as “massive retaliation,” found himself the target of other critics who accused him of speaking too softly about coexistence, particularly after the Chinese branded 13 imprisoned Americans as spies. Dulles’ restraint in this case was deliberate, and resulted from his highly practical analysis of why the Reds made their announcement on the 13 prisoners. He was convinced that the Soviet and Chinese Communists were attempting to give the U.S. a diplomatic one-two punch: soft talk from Moscow and hard action from Peking.

In Paris last fortnight, Dulles analyzed the situation for the NATO foreign ministers’ council. Said he: “At the present time, the U.S. is being subjected to the most severe kind of provocation in Asia. This appears to be deliberately planned in the hope of provoking the U.S. into actions which our European friends and allies would regard as ill-advised and which would perhaps shake our unity at a time when we hope it will be reinforced by the pending London-Paris accords. The U.S. does not intend thus to be hastily provoked into needless action.” This highly practical talk was the more forceful because Dulles’ line had already been proved right. U.S. allies, especially Britain, had been reassured by Dulles’ verbal restraint and had not hesitated to denounce the Reds in terms as strong as any Dulles could have used.

At that kind of diplomatic opinion-molding, John Foster Dulles is a master. He recognizes the importance of communicating his ideas and policies to others, and works hard at checking his circuits of communications. (In his early months as Secretary of State, he would often ask associates, after a Cabinet meeting or a conference, whether he had gotten his ideas across.) When he finds he has been misunderstood, he tries again, tirelessly editing his own public speeches, and even his own thoughts.

In recent months Dulles has gained new confidence that he has found the right words and phrases. His reports to the people, e.g., his report on the Paris Conference at a televised Cabinet meeting, have been remarkable for their sweep and clarity. Dulles considers such reports a key part of his job for one large reason: he believes that the citizens of the U.S. have the right and the ability to understand his business.

As he goes tirelessly about that business, Dulles, at 66, displays a tremendous capacity for concentration and work. Almost all of his waking hours are working hours, whether he is flying across an ocean, seated in his map-lined office or resting at home (the yellow scratch-pad is always at his bedside). His depth of concentration sometimes unnerves staff members who have brought him problems: they think he has forgotten that they are there. His favorite form of relaxation literally gives his staff the shivers: he likes to swim wherever and whenever he can, and sometimes does so, in water more suitable for polar bears than for Secretaries of State.

One-Plan Department. When Dulles travels, his airplane becomes a mobile State Department. He takes with him more aides than made up the entire State Department personnel in John Quincy Adams’ day. (Adam’s fullest staff: eight clerks.) On trips to Europe, the staff is headed by Assistant Secretary (for European Affairs) Livingston T. Merchant and Counselor Douglas MacArthur II. When Asia is the landing place, the Secretary’s chief aide is Assistant Secretary (for Far Eastern Affairs) Walter S. Robertson.

The traveling State Department leaves at home 5,761 colleagues in a sprawling, uncertain organization that is at least two decades overdue for genuine reorganization and reorientation. Dulles has scarcely touched that herculean job, and he may never get around to it. But whoever does may find a legacy from Dulles’ one-plane operation. A sense of policy direction must precede any basic change in the setup of the department; Dulles is providing direction to which the department may be some day geared.

“Pour la Paix.” Obviously, John Foster Dulles goes about his job as a missionary at large rather than as an administrator. At first, some people at home and abroad thought that he was only going to preach. They soon discovered that this missionary did a lot of practicing. He not only carried the word into the jungle, quieted the local tribes and performed marriages, but also helped to clear the ground, dam the streams and stop epidemics of fear.

At year’s end there was evidence that Missionary Dulles was making some converts where conversion was difficult. In Paris, a French foreign office official told a TIME correspondent: “You know, the other day a pamphlet came across my desk. Written in French, it was entitled Pour la Paix. My first reaction was that it was just another Communist propaganda tract. But it wasn’t. It was John Foster Dulles’ recent speech in Chicago. For years now- in Europe at least–the Communists have made `peace’ their private property. Even though people knew what the Communists meant, the idea in their hands helped them and hurt us. It looks now as if your Mr. Dulles is going to take peace away from the Communists and restore it to its real meaning.”

During 1954, as he kept working pour la paix, Foster Dulles disregarded the cries of those who would have had him take the high road toward war or the low road of appeasement. He stayed, instead, on the rutted, booby-trapped road in between, and he made some forward progress. If he has, indeed, captured the word peace for the U.S., his patience and caution were well worth the prize.

Three Tests Ahead. To 1954’s Man of the Year, to his boss, Dwight Eisenhower, and to the people of the U.S. whose destiny they hold, 1955 will bring three critical tests. The immediate problem is the French reaction to the Paris agreements. Somehow, the rearmament of Germany will begin in 1955, whatever stand France takes. The other two tests facing U.S. foreign policy in 1955 are more serious.

After two years in office, the Eisenhower Administration has failed to plug the yawning gap in its foreign policy–the place where history, logic, opportunity and the poverty of the world cry out for U.S. leadership on a free worldwide front of economic advance. In the year’s closing months, the President, despite strong opposition in his own Cabinet, seemed to be moving toward a positive policy for liberalized world trade and stimulated production. Dulles favors such a program. But he has been too busy with the international politics of his job to give it his own leadership: it has little chance of success unless he fights for it–in Washington and abroad.

The second challenge of 1955 is even bigger. Almost certainly, there will be a top-level conference between the Western powers and the Russians. Whatever the paper headed “Agenda” may say, the main business before the meeting will be agreement on atomic weapons. If the U.S. submits to crippling limitation on its power of massive atomic retaliation, it must get in return an equivalent enforceable limitation on the Communist superiority in land armaments and the techniques of subversion.

The prospects of agreement are not bright. But they are less dark than they were before a practical missionary of Christian politics began his extraordinary year of work.

Courtesy of the Congress of the United States:

DULLES, John Foster, a Senator from New York; born in Washington, D.C., February 25, 1888; attended the public schools of Watertown, N.Y.; was graduated from Princeton University in 1908; attended the Sorbonne, Paris, in 1908 and 1909; graduated from the law school of George Washington University, Washington, D.C., in 1911; was admitted to the bar and commenced the practice of law in New York, N.Y., in 1911; special agent for Department of State in Central America in 1917; during the First World War served as a captain and a major in the United States Army Intelligence Service 1917-1918; assistant to chairman, War Trade Board 1918; counsel to American Commission to Negotiate Peace 1918-1919; member of Reparations Commission and Supreme Economic Council 1919; legal adviser, Polish Plan of Financial Stabilization 1927; American representative, Berlin Debt Conferences 1933; member, United States delegation, San Francisco Conference on World Organization 1945; adviser to Secretary of State at Council of Foreign Ministers in London 1945, Moscow and London 1947, and Paris 1949; representative to the General Assembly of the United Nations 1946-1949 and chairman of the United States delegation in Paris 1948; trustee of Rockefeller Foundation; chairman of the board, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace; member of the New York State Banking Board 1946-1949; appointed as a Republican to the United States Senate to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of Robert F. Wagner and served from July 7, 1949, to November 8, 1949, when a duly elected successor qualified; unsuccessful candidate for election to the vacancy; United States representative to the Fifth General Assembly of the United Nations 1950; consultant to the Secretary of State 1951-1952; appointed Secretary of State by President Dwight D. Eisenhower 1953-1959; died in Washington, D.C., May 24, 1959; interment in Arlington National Cemetery, Fort Myer, Va.

Former Secretary of State

John Foster Dulles

Official Funeral

24-27 May 1959

After a long illness, former Secretary of State John Foster Dulles died at Walter Reed General Hospital just before 0800 on 24 May 1959. President Dwight D. Eisenhower received the word at his farm near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Returning to Washington, the President on the afternoon of the 24th directed that Mr. Dulles be given an Official Funeral with full military honors.

Before leaving Gettysburg, President Eisenhower ordered that the flags at the White House and all other government buildings in the United States, except the Capitol, and the flags at American embassies, legations, and consulates abroad be flown at half-staff’ until the burial service for Mr. Dulles had been held. Customarily the flag over the Capitol is lowered only at the death of a President, Vice President, or member of Congress. But at the prompting of Congressman William H. Ayres, Republican of Ohio, who was an ardent admirer of Mr. Dulles, the Congressional leadership-Vice President Richard M. Nixon, Senate Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson, and Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn – instructed the Capitol Architect, J. George Stewart, to fly the Capitol flag at half-staff for Mr. Dulles. Many foreign embassies including that of the Soviet Union voluntarily lowered their flags also.

The funeral for Mr. Dulles was the first one conducted after policies and general plans for the Official Funeral had been issued late in 1949 and published with revisions in 1958. (The funeral held for James V. Forrestal early in 1949 resembled the Official Funeral.) The ceremonies of the Official Funeral were only slightly less elaborate than those of the State Funeral; the main difference was that the Official Funeral did not include a period of lying in state in the rotunda of the Capitol.

Chief responsibility for arranging the funeral rested with the Department of State and Headquarters, Military District of Washington. As prescribed in the existing funeral policies, the Department of State was responsible for coordinating all funeral arrangements since it was the department of which Mr. Dulles had been a member. The Commanding General, Military District of Washington, as the representative of the Secretary of the Army, who in turn represented the Secretary of Defense, was in charge of arranging all armed forces participation in the ceremonies. President Eisenhower also instructed Brigadier General Andrew J. Goodpaster, White House Staff Secretary, to see that the wishes of Mrs. Dulles were followed implicitly.

According to the plans developed, Mr. Dulles’s body was to lie at the Dulles residence in Washington from noon on 25 May until noon on the 26th, when it was to be moved to the Washington National Cathedral. There the body was to lie in the Bethlehem Chapel until noon on 27 May, and the funeral service was to be held in the nave of the cathedral at 1400 on the 27th. Mr. Dulles himself was a Presbyterian and had been an elder of the National Presbyterian Church in Washington. The cathedral, a Protestant Episcopal Church, was selected for the funeral service because of its large seating capacity of 2,800. The Reverend Roswell P. Barnes of New York, secretary of the World Council of Churches and long-time friend of Mr. Dulles, was to lead the clergymen officiating at the service. To assist him were the Reverend Paul A. Wolfe of the Brick Presbyterian Church, which was Mr. Dulles’s church when he was in New York, and the Reverend Edward L. R. Elson of the National Presbyterian Church in Washington. Burial was to take place in Arlington National Cemetery, by virtue of Mr. Dulles’s service as a commissioned officer on the War Trade Board during World War I. The gravesite, selected by Mrs. Dulles, was in Section 21, not far southwest of the Memorial Amphitheater.

Mr. Dulles’s body was taken from Walter Reed General Hospital to the Dulles residence at noon on 25 May by morticians from Gawler’s Funeral Home. At 1100 on the following day, the casket was moved by hearse to the Washington National Cathedral. Six military body bearers (two Army, one Marine Corps, one Navy, one Air Force, and one Coast Guard) handled the casket. In addition, the small motorized cortege moving to the cathedral included the mortician, the clergy, and members of the Dulles family. Mrs. Dulles herself remained at home. The cortege halted on the drive at the south entrance to the cathedral. An honor cordon representing all services including the Coast Guard flanked the driveway curb and the walkway to the entrance. Inside this cordon was a second cordon of friends and associates of the former Secretary whom Mrs. Dulles had selected to act as honorary pallbearers:

- Thomas E. Dewey

- Edward H. Green

- C. Douglas Dillon

- Charles C. Glover

- George M. Humphrey

- Robert F. Hart, Jr.

- Jean Monnet C. D.

- Jackson Joseph

- Herbert C. Hoover, Jr.

- E. Johnson

- John D. Rockefeller 3d

- George Murnane

- Admiral Arthur W. Radford

- Herman Phleger

- General Walter B. Smith

- Dean Rusk

- General C. Stanton Babcock

- Eustace Seligman

- Pemberton Berman

- Henry P. Van Dusen

- Arthur H. Dean

- Morris Hadley

- Harold Dodds

Near the double cordon stood a national color detail and the verger of the cathedral. Inside the Bethlehem Chapel waited some eighty members of the diplomatic corps headed by Mr. Wiley Buchanan, the Chief of Protocol of the Department of State. Also at hand was a joint honor guard, the first relief of which would take post around the casket as soon as it was brought into the chapel.

When members of the cortege had left their automobiles, the body bearers removed the casket from the hearse and a small procession formed to escort the body into the chapel, the national color detail leading the way. Dr. Barnes and the cathedral verger preceded the casket and behind it came the honorary pallbearers and members of the Dulles family.

Moving through the honor cordon and a cathedral corridor, the body bearers placed the casket on a velvet-covered bier in the center of the chapel. Floral tributes had been arranged earlier and a square of velvet rope surrounded the closed casket. The first relief of the guard of honor took post inside the rope, one sentinel at each corner of the bier, the officer in charge at the head of the casket. The Dulles family, honorary pallbearers, and members of the diplomatic corps gathered outside the rope. In this setting, Dr. Barnes read from Psalms and offered a prayer.

At the conclusion of this simple ceremony, about 1230, members of the public were allowed to enter the chapel, which remained open through the night and until 1100 on 27 May while thousands of people came to pay their respects.

On the 27th, in preparation for the funeral service at 1400, troops supplied by the Military District of Washington reported at the cathedral at 1000 to complete arrangements for controlling automobile traffic and parking. At noon twenty seven ushers and twenty guides arrived to prepare for handling the movement and seating of persons attending the service. All were of the grades of major or lieutenant colonel, or the equivalent. The ushers represented all the uniformed services (nine Army, three Marine Corps, six Navy, six Air Force, and three Coast Guard), while the guides were Army officers. In charge of both ushers and guides was an officer from the Military District of Washington.

Troops to cordon off the ceremonial area around the entrance to the cathedral reported at 1230. An officer and six men of a floral detail also arrived to handle the transfer of flowers within the cathedral and from the cathedral to Arlington National Cemetery. About 1300 the body bearers, who again represented all the armed forces, arrived and Mr. Dulles’s casket was borne from the Bethlehem Chapel to the nave of the cathedral. At the same time the national colors were posted in the main chapel and the guard of honor took post around the casket.

Shortly afterward invited guests and the first members of the official funeral party, including members of the cabinet, justices of the Supreme Court, members of Congress, and state and territorial governors, arrived. About 1345 distinguished foreign dignitaries, the honorary pallbearers, and a special honor guard were ushered into the cathedral. Among the foreign dignitaries were Chancellor Konrad Adenauer and Mme. Chiang Kaishek; the foreign ministers of Great Britain, France, West Germany, Turkey, Italy, the Netherlands, and the Soviet Union; and the Secretary General of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Paul-Henry Spaak. The special honor guard included the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Army Chief of Staff and Vice Chief of Staff, the Chief of Naval Operations and the Vice Chief of Naval Operations, the Chief of Staff and Vice Chief of Staff of the Air Force, the Commandant and Assistant Commandant of the Marine Corps, and the Commandant and Assistant Commandant of the Coast Guard. Over the next fifteen minutes, Vice President Nixon and his party, President Eisenhower and his party, and Mrs. Dulles and her family were ushered to their seats. Upon the arrival of Mrs. Dulles, the guard of honor around the casket retired, and the funeral service was begun.

At the opening of the service a hymn, “O God, Our Help in Ages Past,” was sung by a choir of thirty boys marching down the aisle from the north transept of the cathedral. Dr. Wolfe, Dr. Elson, and Dr. Barnes in turn offered prayers and read from the Old and New Testaments. As Mrs. Dulles had requested, no eulogies were delivered.

At the conclusion of the service, about 1430, the honorary pallbearers left the cathedral to form a cordon outside the entrance. When they were in position, the procession formed, the color detail leading. The clergy preceded the casket, which was followed by the personal flag bearer, the Dulles family, President Eisenhower and his party, Vice President Nixon and his party, the mortician, and the rest of the official funeral party. Members of the procession moved directly to vehicles for the journey to Arlington National Cemetery.

After the body bearers placed the casket in the hearse, they stood fast with the national color detail while the cortege formed and departed for the cemetery. The body bearers, the color detail, and the floral detail, escorted by police, then moved by a separate route to arrive at the cemetery ahead of the procession.

Except for the escort commander, Colonel Milton S. Glatterer, the deputy commander of the Military District of Washington, the military escort did not participate in the move from the cathedral to the Memorial Gate of the cemetery. The following order of march was observed: police escort, escort commander, special honor guard, mortician, clergy, hearse, Dulles family, President Eisenhower, Vice President Nixon, honorary pallbearers, other dignitaries, police escort. The motorized cortege moved to Memorial Gate via Woodley Road, 34th Street, Massachusetts Avenue, Rock Creek Parkway, Memorial Bridge, and Memorial Drive. It took twenty-five minutes to reach the gate.

On the green at the gate, the military escort was on line facing the approaching cortege. The U.S. Army Band was at the right of the formation. To the left of the band, in order, stood a company-size contingent each from the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, and Coast Guard. To the left of these troops was a composite company of servicewomen and, finally, a group composed of representatives of seven national veterans’ organizations chartered by Congress. The caisson and body bearers were waiting in the street opposite the center of the escort formation for the casket transfer ceremony.

When the cortege reached the gate, guides directed each section to its proper position for the transfer ceremony. The special honor guard, leading the procession, formed three cars abreast on the left side of Memorial Drive. The car carrying the clergy joined this formation. The hearse was at first guided to a position on Schley Drive to the rear of the caisson. The cars bearing the Dulles family formed on the right side of the road, the one carrying Mrs. Dulles in front by itself, the others behind, three abreast. To the rear of the family cars were those of the Presidential and Vice Presidential parties, three abreast, and behind these, also three abreast, were the automobiles of the honorary pallbearers. The rest of the cortege was in column, two cars abreast, on the right side of Memorial Drive.

When all cars were in position, the hearse moved forward and halted at the left and a few feet ahead of the caisson. The body bearers and personal flag bearer then moved into position behind the hearse. The military escort presented arms and held the salute while the Army Band played ruffles and flourishes, a slow march, and then a hymn. As the hymn was begun, the body bearers removed the casket from the hearse and carried it to the caisson. The hearse left the area. After the casket was secured on the caisson, the band ceased playing and the military escort ordered arms, completing the transfer ceremony.

The procession then moved toward the gravesite, starting south on Roosevelt Drive. Behind the escort commander, the military units marched in column in the same order in which they had formed in line on the green at Memorial Gate. The cortege followed much the same arrangement as in the movement from the cathedral. The following order of march was observed: escort commander, US Army Band, Army contingent (89), Marine Corps contingent (89), Navy contingent (89), Air Force contingent (89), Coast Guard contingent (89), servicewomen contingent (102), veterans’ group, special honor guard, national colors, mortician, clergy, caisson, personal colors, Dulles family, President Eisenhower, Vice President Nixon, honorary pallbearers, other mourners. The procession reached the gravesite via Roosevelt, Wilson, Farragut, McPherson, and Lawton Drives. The cortege halted on Lawton Drive, which was just north of the gravesite. The military escort continued past the site, then turned back on Porter Drive to reach its assigned position just south of the grave. Upon reaching this position, the escort units halted facing the gravesite; the Army Band played a hymn while other members of the procession, on Lawton Drive, left their cars. The grave chosen by Mrs. Dulles was on the brow of a shaded hill. On one side the floral detail had arranged over a hundred floral tributes. On the north side, a canopy had been erected to provide shelter from the sun for the Dulles family and the highest government officials; the temperature was-in the eighties. From the grave, a carpeted aisle reached to Lawton Drive, and the caisson had been halted beside it.

The honorary pallbearers, among the first to dismount, took position on either side of the aisle. At the same time, the special honor guard was guided to its graveside position. The remaining mourners stayed on the roadway after leaving their automobiles.

When the members of the Dulles family, last to dismount, were out of their cars, the military escort presented arms and held its salute throughout the procession to the grave. The band sounded ruffles and flourishes and played a march, then began a hymn. As the hymn was played the body bearers removed the casket from the caisson. Preceded by the national colors and the clergy, and followed by the personal flag; the casket was borne between the cordon of honorary pallbearers. When it had passed, the pallbearers fell in behind and moved to their graveside position. The body bearers placed the casket on the lowering device. At that time, the band stopped playing the hymn and the escort unit ordered arms. The body bearers then raised the flag that had draped the casket and held it over the casket throughout the graveside service.

Under the direction of the superintendent of Arlington National Cemetery, Mr. John C. Metzler, the Dulles family and the President and Vice President and their parties were escorted to seats under the canopy at the graveside. All other mourners then were guided to a position behind the seated group. When everyone had found his place, Dr. Elson read the Twenty-third Psalm. Dr. Barnes then continued the service. At its conclusion, the military escort presented arms while the battery of the 3d Infantry, from a distant position in the cemetery, fired a 19gun salute. At the end of the cannon salute, a rifle squad from the 3d Infantry fired three volleys, and a bugler sounded taps. In the traditional manner the body bearers then folded the flag they had held over the casket and handed it to the cemetery superintendent. Mr. Metzler, in turn, gave it to a clergyman who presented it to Mrs. Dulles, thus concluding the funeral rites for former Secretary of State John Foster Dulles.

DULLES, JANET WIDOW OF JOHN

- DATE OF BIRTH: 05/31/1891

- DATE OF DEATH: 05/14/1969

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 05/17/1969

- BURIED AT: SECTION SPEC SITE LOT 31 L

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

- WIFE OF JF DULLES

DULLES, JOHN FOSTER

- MAJOR LAISON OFF BET WAR DEP WAR TRADE BOARD OFF CH OF ST

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: Unknown

- DATE OF BIRTH: 02/25/1888

- DATE OF DEATH: 05/24/1959

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 05/27/1959

- BURIED AT: SECTION SPEC SITE LOT 31 R

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard