Courtesy of the United States Air Force

Elwood Quesada was a member of the famous Question Mark endurance crew of 1929. In the first week of January, Second Lieutenant Quesada flew as a crew member with Major Carl Spaatz, Captain Ira Eaker, and others in the Question Mark plane which set a sustained inflight refueling record of 151 hours – more than six days in the air over Los Angeles. The trimotor Fokker with Wright engines flew 11,000 miles and was refueled 43 times; nine refuelings were at night.

Elwood Richard Quesada was born in 1904 in Washington, D.C. Elwood “Pete” Quesada attended the Wyoming Seminary in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, the University of Maryland, and Georgetown University. Quesada enlisted in September 1924 as a flying cadet and received his wings and commission in the Air Reserve one year later. He was inactive for one and a half years but in September 1927 went on duty as an engineering officer at Bolling Field, Washington, D.C., where he served until June 1928. He became aide to Major General James Fechet, then chief of the Air Corps.

Quesada went to Cuba as assistant military attache from October 1930 until April 1932. He returned to Bolling Field and was promoted to first lieutenant in November. Lieutenant Quesada became aide to F. Trubee Davison who was assistant secretary of war for air. Lieutenant Quesada flew Davison and explorer Martin Johnson all over Africa on a mission to collect animals for the New York Museum of Natural History in the summer of 1933.

Quesada was chief pilot on the New York-Cleveland route when the Army men flew the airmail in 1934. One year later he became commanding officer of Headquarters at Langley Field, Virginia. He was promoted to captain in April 1935. Quesada served as aide to General Hugh Johnson, administrator of the NRA, and then Secretary of War Dern. Quesada completed the Command and General School course at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, in June 1937 and went to Mitchel Field, New York, as flight commanding officer of the 1st Bomb Squadron.

His tour ended in June 1938 when he went to Argentina for two and a half years as technical advisor to Argentina’s air force. He was assigned to intelligence in the Office of the Chief of Air Corps in October 1940 with promotion to major in February 1941. Quesada returned to Mitchel Field in July 1941 as commanding officer of the 33d Pursuit Group. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel in January 1942 and in July took command of the Philadelphia Region of the 1st Fighter Command. Quesada became brigadier general in December 1942 and commanding general of the 1st Air Defense Wing at Mitchel Field. He took this wing in early 1943 to Africa where he also commanded the 12th Fighter Command and was deputy commanding general

of the Northwest African Coastal Air Force. He participated in many operational flights during the Tunisian, Sicilian, Corsican and Italian campaigns, and remained head of the 12th until the landings in Italy were secured.

Going to England in November 1943 as commanding general of the 9th Fighter Command, Quesada established advanced Headquarters on the Normandy beachhead on D-Day plus one, and directed his planes in aerial cover and air support for the Allied invasion of the continent.

Quesada became commanding general of the 9th Command and the 9th Tactical Air Command in Europe in November 1943. In April 1944 he became a major general. Quesada returned to the United States in June 1945 as assistant chief of air staff for intelligence at Headquarters Army Air Forces. General Quesada went to Tampa, Fla., as commanding general of the Third Air Force on March 1, 1946. This group soon became Tactical Air Command. As head of TAC he was promoted to lieutenant general in October 1947 and in November 1948 became special assistant for reserve forces at Headquarters U.S. Air Force.

General Quesada headed the Joint Technical Planning Committee for the Joint Chiefs in September 1949. He was designated commander of Joint Task Force-3 in that office in November 1949. Quesada retired October 31, 1951. He was director of the Federal Aviation Agency from 1958-1961. Quesada has held executive positions with Olin Industries, Lockheed Aircraft, Topp Industries, and American Airlines.

General Elwood Quesada’s medals and awards include Distinguished Service Medal with oak leaf cluster; Distinguished Flying Cross; Purple Heart; Air Medal with two silver stars; American Defense Service Medal; European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal and seven bronze battle stars; World War II Victory Medal; British order of Bath (Degree of Companion); Commander of British Empire; French Legion of Honor; French Croix de Guerre with Palm; Luxembourg Croix de Guerre;

Order of Adolphe of Nassau; Polish Pilot Badge; Conmandeur de l’Ordre de la Couronne with Palm; Croix d’Officier de l’Order de la Couronne with Palm.

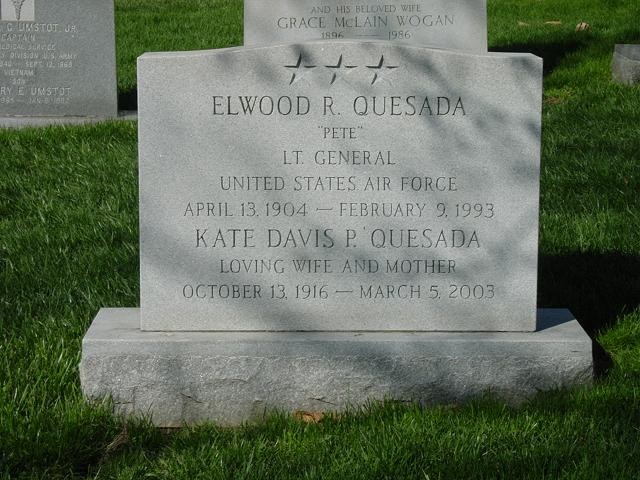

General Quesada died on February 9,. 1993 and was buried with full military honors in Section 30 (Grave 439) of Arlington National Cemetery.

By Jim Garamone

American Forces Press Service

WASHINGTON, Sept. 11, 2000 — He was an aviation pioneer, an organizer of Allied victory during World War II and a Hispanic American.

He was Elwood R. “Pete” Quesada.

Quesada was the son of a Spanish businessman and an Irish-American mother. His military career spanned aviation history from post-World War I era biplanes to supersonic jets.

Quesada was born in Washington, D.C., in 1904, a few months after the Wright Brothers flew at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. He grew up with aviation.

World War I imposed hothouse growth on all things connected with planes. In 1914, when the war began, primitive aircraft scouted enemy formations. They did not fire at each other nor did they drop bombs on the enemy troops. The

aviators themselves began the first moves toward arming the craft. The pilots shot at each other first with pistols and rifles and then machine guns. Bombs and rockets came next.

The U.S. Army used aircraft to good effect during the St. Mihiel offensive of 1918.

All through the war, the opposing sides developed planes that flew longer, farther, faster and could do more things. After the war, aircraft development continued. The 1920s were a time of experimentation. Plane design changed from biplanes at the beginning of the decade to sleek monoplanes by the end.

Quesada started his military career in the middle of this ferment. He entered the Army Air Service as a flying cadet in 1924. He went through flight school at what is now Brooks Air Force Base, Texas (then called Brooks Field) and

advanced training at neighboring Kelly Air Force Base.

Having only a reserve commission, Quesada found the active Army Air Service had no space for him. He returned to civilian life, playing baseball for the St. Louis Cardinals. In 1927, he returned to the Air Service and received a Regular Army commission. He reported to Bolling Field in Washington.

Bolling Air Force Base is now an administrative center, but its runways in 1927 were full of aircraft flown by some of the most innovative thinkers in the Army Air Corps. Pete Quesada joined then-Major Carl “Tooey” Spaatz and then-Captain Ira Eaker in developing air-to-air refueling.

On January 1, 1929, a three-engine Fokker C-2A rose into the air from metropolitan Airport in Los Angeles. It did not land again until January 6. Quesada, Spaatz and Eaker shared piloting duties aboard the plane, dubbed the “Question Mark.”

Throughout their five days aloft, the Fokker crew took in fuel from a Douglas C-1C that passed a hose in flight — as well as oil, water and food. In all, the Fokker crew made 37 mid-air transfers and flew more than 11,000 nonstop

miles.

Today, air-to-air refueling is almost routine. The United States bases the B-2 bomber in Missouri, knowing that no spot on the globe is too far away thanks to inflight refueling. This started with the flight of the Question

Mark.

But Quesada’s larger contribution came during World War II. The fabulous Allied air-ground machine that chewed up Nazi forces in Europe didn’t just materialize. It was Quesada’s baby.

Even before the war, Quesada — like many others — had been thinking of the place of air power. But where others looked to strategic bombing, Quesada concentrated on the tactical application of air power. During classes at

Maxwell Field, Alabama, and at the Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, Quesada began to build the concept of close air support. He predicted the next war would require “all sorts of arrangements between the air and the ground, and the two will have to work closer than a lot of people think or want.”

He got the chance to put his theories into practice. In December 1942, he was promoted to brigadier general and sent to North Africa to command the 12th Fighter Command. He put his ideas through the crucible of combat, and they evolved into Army Air Forces field regulations “Command and Employment of Air Power,” published in July 1943.

At the heart of these regulations is the premise that air superiority is the prerequisite for successful ground operations. Further, he said, the air and ground commanders must be equals and there had to be centralized command of air assets to exploit the flexibility of air power.

In October 1943, Quesada went to England and assumed command of the 9th Fighter Command and readied that unit for the Normandy invasion. During the build-up and breakout that followed the invasion, Quesada was at his best. He placed forward air observers with divisions on the ground, and they could call for air support. He mounted radios in tanks so ground commanders could contact pilots directly. He pioneered the use of radar to vector planes during attacks. This was particularly helpful during the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944, when bad weather hid many German targets.

The air-ground apparatus he put together was the best in the world. After the war, he was the first commander of TAC — the Tactical Air Command. He moved the headquarters from Tampa, Fla., to Langley Air Force Base, Virginia, so he could be close to the headquarters of the Army Ground Forces. When the Air Force became a separate service in 1947, he went along as a lieutenant general.

Quesada retired from the Air Force in 1951. He was disillusioned with the emphasis placed on Strategic Air Command at the expense of tactical air. He served as the first head of the Federal Aviation Administration and held positions in private firms.

Quesada died in Washington in 1993

QUESADA, KATE DAVIS

Kate Davis Quesada of Hobe Sound, Florida, died on March 5, 2003, in Scarborough, Maine at age 86.

She was the Granddaughter of Joseph Pulitzer, founder of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, daughter of Joseph and Elinor Wickham Pulitzer, widow of Captain Henry Ware Putnam who died in the Pacific in 1945, and Lieutenant General Elwood R. ”Pete” Quesada, who died in 1993.

She is survived by two daughters, Kate Baxter of Inverness, California and Hope W. Putnam, of South Freeport, Maine, and two sons, Thomas R. Quesada and Peter W. Quesada, both of South Freeport, Maine, and six grandchildren, as well as, her sister, Elinor Hempelmann of Santa Fe, New Mexico, and her brother Michael E. Pulitzer of St. Louis, Missouri.

A memorial service will be held in Hobe Sound, Florida, on Tuesday, March 25, at 5PM. Burial will be in Arlington Cemetery, the next day.

Contributions in her memory may be made to the Maine Coast Heritage Trust, Bowdoin Mill, 1 Main Street, Suite 201, Topsham, Maine. 04086.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard