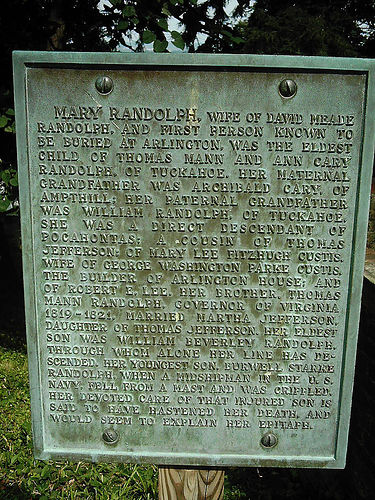

The FIRST person ever buried on the grounds which would become Arlington National Cemetery. She was a cousin of Mary Lee Fitzhugh Custis, wife of George Washington Parke Custis, the builder of Arlington. She died in 1828 and buried on the estate in what would become Section 45.

Grave stone inscription:

“In the memory of Mrs. Mary Randolph,

Her intrinsic worth needs no eulogium.

The deceased was born

The 9th of August, 1762

at Amphill near Richmond, Virginia

And died the 23rd of January 1828

In Washington City a victim to maternal love and duty.”

There is an unusual story about Mrs. Randolph, so I will begin her story with her gravesite at Arlington House, formerly known as the Custis Mansion and currently the site of Arlington National Cemetery.

By 1929 her name was forgotten as noted by Washington journalist, Margaret Husted, in the Washington Star. The article stated that workers for the War Department, which administered Arlington National Cemetery and Arlington House, became curious about the grave of “Mrs. Mary Randolph”. The grave, which is located one hundred feet north of the Custis mansion, was noticed as renovation to the house began. No one working on the project knew who she was or why she had been buried there. Her gravestone stated that she was born on August 9, 1762, at Ampthill (near Richmond, Virginia) and she died on January 23, 1828 in Washington City.

After the story was published, Mrs. Randolph’s descendants identified the mysterious lady. She was the cousin of George Washington Parke Custis and the godmother of his daughter, Mary Randolph Custis, who married Robert E. Lee. Mary Randolph was the first person ever buried on the grounds of what would become Arlington National Cemetery. Her tombstone inscription reads: “Her intrinsic worth needs no eulogium. The deceased was a victim to maternal love and duty. As a tribute of filial gratitude this monument is dedicated to her exhaulted virtue by her youngest son”. Her youngest son, Burwell Randolph, had suffered a crippling fall while in the Navy. He declared that she had sacrificed her life in the care of his.

Mary was born at Ampthill, the plantation of her maternal grandparents in Chesterfield County, and now the site of the Dupont Company. (The house was dismantled and moved to Richmond in 1929.) Mary Randolph was a member of the Virginia elite, with roots extending back to the colony’s formative years. As the eldest of thirteen children of Thomas Mann and Ann Cary Randolph of Tuckahoe in Goochland County, she grew up surrounded with all the wealth and comforts enjoyed by families in the plantation homes. A tutor provided formal education for Mary and her siblings.

Along with her formal education, Mary Randolph was trained in proper household management practices, a quality expected of upper-class women of the time. Women were expected to supervise large manor houses with supporting buildings and numerous servants. “Mary Randolph: A Chesterfield County role model for women of the 19th century”, states that women were relegated to secondary positions within the family hierarchy, but in truth they were the mainspring that kept the household running. Women of this period had numerous responsibilities for the household supported by a formable knowledge of food preservation and preparation and elegant entertaining. This knowledge was important throughout Mary Randolph’s adult life.

Mary wed David Meade Randolph of Presque Isle, Chesterfield County (a first cousin once removed) in December 1780. He was known as an outstanding farmer and noted inventor. He served as a captain in the Revolutionary War and was later appointed as a United States Marshal (a federal court official) for Virginia by President Washington. It is believed that Mr. Randolph’s cousin, Thomas Jefferson, endorsed the appointment. The couple produced eight children and four survived to adulthood: Richard, William Beverly, David Meade and Burwell Starke.

Much of the land that made up the 750 acre plantation was swampy and therefore a health hazard. The family left the Presque Isle plantation to live in Richmond. They built a brick home at Fifth and Main Streets in Richmond. The home, named “Moldavia”, became the center of Federalist society. Along with the Marshalls, the Wickhams, the Chevallies and other prominent Richmond families, the Randolphs established a model for fashionable social life. With Mary’s knowledge of food and entertaining, invitations to dine in the Randolph home were coveted. Mary’s skills as a hostess and cook were well known in the Richmond area. In fact, her reputation was so widespread that during the slave insurrection near Richmond in 1800, the leader “General” Gabriel announced that he would spare her life so that she could become his cook.

In 1802, President Thomas Jefferson removed David Randolph, an outspoken Federalist, from office as a United States Marshall. Although the two men were cousins, they were on opposite sides politically and kinship proved less important than party ties. Losing the court position in combination with other business reversals, contributed to the decline of Randolph’s fortune. His removal from office coincided with a ruinous fall in tobacco prices and a resulting recession in 1800-1802. David and Mary found that they had to make severe cutbacks in their household, which had not been an economical one. The Randolphs offered sundry lots and tenements in Richmond for sale. They listed Moldavia for sale between 1802 and 1805 and moved into a rented house. There are two conflicting stories on who purchased the house. According to Margaret Husted, John Allan, foster father of Edgar Allan Poe purchased Moldavia, however Sterling Anderson reported that Joseph Gallego, the owner of Gallego Flour Mills, purchased the home.

Mary Randolph took an unorthodox step for an upper-class woman so that her family could continue to enjoy their accustomed standard of living. In March 1808, she advertised in the Richmond Virginia Gazette that she was opening a boarding house for ladies and gentlemen. Martha Jefferson Randolph, Mary’s sister-in-law, was not optimistic about the outcome of this new venture. Martha wrote her father “‘Sister Randolph’–whose house servants had been saved, at least temporarily, through a prior mortgage–had “opened a boarding house in Richmond, but… has not a single boarder yet.'”. Martha believed ‘the ruin of the family is still extending itself daily.'” Despite these doubts, Mary achieved success in her enterprise. Dubbed “the Queen”, she attracted, ” as many subjects as her domain could accommodate. There were few more festive boards… wit, humor and good fellowship prevailed, but excess rarely”.

It is interesting to note that all the cookery at that time was done in kitchens that had changed little over the centuries. In Virginia, the kitchen was typically a separate building for reasons of safety, summer heat and the smells from the kitchen. The heart of the kitchen was a large fireplace where meat was roasted and cauldrons of water and broth simmered most of the day. Swinging cranes and various devices made to control temperature and the cooking processes were used. The Dutch oven and the chafing dish were found in most kitchens. The brick oven used for baking was located next to the fireplace. A salamander was used to move baked products around in the oven and it could also be heated and held over food for browning. Karen Hess stated that Mrs. Randolph was a fine practitioner who knew her way about the kitchen but the actual cooking and toil fell to the servants.

In the same year that Mary opened her boarding house, David became an agent for Henry Heth in the operation of the Black Heth Coal Mines near Midlothian. David traveled to England and Wales to study their mining operations and to improve those in the Black Heth Mines. Always interested in turning a profit, David received patents in 1815 for his improvements in shipbuilding and candle making and in 1821 for improvements in drawing liquor. For his relative, George Washington Parke Curtis, he invented a special compound to waterproof Arlington, the Custis mansion. Mrs. Randolph is said to have invented an icebox, however someone else saw it and patented it in his own name.

By 1819, the couple, in advancing years, gave up their business enterprises and moved to Washington, D. C. to live with their son, William Beverley Randolph. At this residence, Mary decided to compile her culinary knowledge and her cookbook was published in 1824. In her preface to The Virginia Housewife, Mrs. Randolph points out the lack of clear-cut instructions in the cookbooks of that time. “The difficulties I encountered when I first entered on the duties of a house-keeping life, from the want of books sufficiently clear and concise to impart knowledge to a Tyro, compelled me to study the subject, and by actual experiment to reduce everything in the culinary line, to proper weights and measures.” She also offered three rules for running a household: “Let everything be done at the proper time, keep everything in its proper place, and put everything to its proper use.” At the beginning of his article, “‘Queen Molly’ and the Virginia Housewife” Sterling Anderson quoted Mrs. Randolph with this statement: “The government of a family bears a Lilliputian resemblance to the government of a nation. The contents of the Treasury must be know, and great care taken to keep the expenditures from being equal to the receipts.” Mrs. Randolph’s philosophy is illustrated in additional quotes from Anderson’s article: “The prosperity and happiness of a family depend greatly on the order and the regularity established in it. Management is an art that may be acquired by every woman of good sense and tolerable memory.”

Mrs. Randolph’s cookbook was written especially for Virginia cooks. Mrs. Husted reported that during the colonial period wealthy families imported cookbooks from England, but these books ignored the special requirements of the New World. Mrs. Randolph’s book proves that regional food preferences were well established by the first quarter of the 19th century. She included recipes for dishes that have remained southern favorites, such as “toasting ham”; baking, roasting or broiling of shad, boiling turnip tops “with bacon in the Virginia style”; sweet potato pudding; cornmeal bread; batter cakes; and batter bread. Thomas Jefferson’s granddaughter, Virginia Randolph Trist, had a copy of the manuscript collection of recipes of Martha Jefferson Randolph and the collection contained over fifty recipes from Mary Randolph’s cookbook. Husted also stated The Virginia Housewife was surprisingly modern. Absent were the elaborate dishes of the 18th century cookbooks and the overwhelming array of foods featured on English bills of fare. Mrs. Randolph believed that the quality of prepared food, not its great variety, was important. She wrote that: “Profusion is not elegance”. Recipes for breads and hot cakes occupy a large section of Mary Randolph’s book. She provides recipes for battercakes containing small hominy, cornmeal, butter, eggs and milk, which were baked on a griddle or in “woffle irons”. A popular recipe was the one for Apoquiniminc Cakes or beaten biscuits.

Mrs. Randolph also promoted the charm of gathering and preparing garden-fresh vegetables. It was not on her recommendation that a later generation of southern cooks followed the ruinous practice of cooking vegetable endlessly. She stressed repeatedly that vegetables must be cooked only to the point of being tender. Mrs. Randolph advocated the common practice of using herbs, spices and wines in cooking. Her recipe for apple fritters calls for slices of apple marinated in a combination of brandy, white wine, sugar cinnamon, and lemon rind.

Cookbooks, with few exceptions, are addressed to housewives in comfortable circumstances. The poor, with lean larders, have little use for recipes that assume a plentiful supply of ingredients. The Virginia Housewife was intended for those who enjoyed the bounty of plantation life. Mrs. Randolph did have an eye for economy, for example, she offered several ways of using bread in simple family desserts such as bread pudding and bread fritters. In her article, Margaret Husted stated that in spite of Mary Randolph’s hostility to Thomas Jefferson for ousting her husband from office, she was not reluctant to accept vanilla beans and macaroni products, which were unknown in Virginia until Jefferson introduced them. Recipes for ice cream were also included in her book. Mrs. Randolph concluded her cookbook with various domestic hints such as how to make starch, soap, and blacking. She also included directions for cleaning knives, forks and silver utensils. The recipe for an early room deodorizer, vinegar of the four thieves, was also included in the cookbook.

In Virginia, Mary Randolph’s cookbook has become synonymous with fine cuisine. Karen Hess, a culinary historian, wrote that the most influential American cookbook of the 19th century was this book. The Virginia Housewife was not only acclaimed in Virginia, but many of the recipes have been copied in cookbooks published all over the United States. Mrs. Randolph died in 1829 before the full extent of her triumph was apparent. After her death, her cookbook was published in six editions over the next three decades. Her son, William Beverly Randolph, copyrighted the cookbook in 1828. Her recipes showed simplicity of concept; they were clearly expressed; and they were full of perceptive observations.

Jan Carlton commented that Mary Randolph combined knowledge of English cooking with native Indian food influences. She reflected her knowledge by combining the use of regional meats and vegetables with overall cooking techniques and social grace. Further, she introduces into her recipes the use of African food ingredients, a knowledge gained from servants. When Ms Hess reviewed the Virginia Housewife, she remarked that nothing in the history of early American cookbooks quite prepares us for the sumptuous cuisine presented. Mrs. Randolph brought her personal flair to everything she did, but her reputation as Virginia’s best cook and the early success of her work indicates that her cookery was solidly based in Virginia tradition. Already there was a sophisticated cuisine, a harmonious interweaving of several food cultures added to the fine cooking of the 17th and 18th centuries. Now there seemed to be an authentic American cuisine.

Mary Randolph:

A Chesterfield County (Virginia) role model for women of the 19th century

The government of a family bears a Lilliputian resemblance to the government of a nation. The contents of the Treasury must be known, and great care taken to keep the expenditures from being equal to the receipts. A regular system must be introduced into each department, which may be modified until matured, and should then pass into inviolable law. The grand arcanum of management lies in three simple rules: “Let every thing be done at the proper time, keep every thing in its proper place, and put every thing to its proper use.”

So began Mary Randolph’s preface to The Virginia Housewife, a cookbook that became so popular it has rarely been out of print since it was first published in 1824.

Born in 1762 at Ampthill, her grandfather’s Chesterfield County plantation, now the site of the Dupont Company (the house itself was dismantled and moved to Richmond in 1929), Mary Randolph was a member of the Virginia elite, with roots extending back to the colony’s formative years. As the eldest child of Thomas Mann and Ann Cary Randolph of Tuckahoe in Goochland County, she grew up surrounded with all the wealth and comforts enjoyed by other members of her class. She and her numerous siblings were tutored by Peter Jefferson, father of the nation’s fourth president, to whom she was related by both blood and marriage.

Along with her formal education, Mary was trained in the proper household management expected of upperclass women of the time, women who were brought up to supervise large manor houses with surrounding support buildings and numerous servants. While women then were relegated to secondary positions within the family hierarchy, they were in truth the mainspring that kept the household running. These women had enormous responsibilities as well as formidable knowledge, part of which was an awareness of food preparation and elegant entertaining. This knowledge would sustain Mary Randolph throughout her adult life.

In 1780, Mary married a cousin, David Meade Randolph, and they settled in Chesterfield County near Bermuda Hundred at Presquile, a 750-acre plantation that was part of the Randolph family’s extensive property along the James River. While David Randolph saw to the cultivation of his plantation, gaining a reputation as “the best farmer in the country,” as well as a noted inventor, Mary assumed a conventional role, supervising the household, entertaining their many guests and acquiring a reputation as a lively hostess who set an exquisite table. While living at Presquile, Mary bore four sons.

Over time, life at Presquile, situated along the swamp lands of the James, proved difficult. According to a contemporary source, the swamps produced noxious fumes that brought on “frequent and dangerous diseases. Mr. Randolph is himself very sickly, and his young and amiable wife has not enjoyed one month of good health since she first came to live on this plantation.” By 1798, the family had moved to Richmond, where they built a house, christened “Moldavia” (a combination of their two given names) by a friend. Presquile was sold out of the Randolph family three years later.

Richmond welcomed the young couple. Mary, already well known for her accomplishments, “charming manners, and … masculine mind,” quickly established a reputation as one of the city’s leading hostesses. As the United States marshal of Virginia under two administrations (that of George Washington and John Adams), David gained attention as an outspoken Federalist, and Moldavia became a center for Federalist society. The Randolphs entertained lavishly. With Mary’s knowledge of fine food and entertaining, invitations to dine at the Randolphs’ table were coveted.

Mary’s skills as hostess and cook were so well known, in fact, that they were brought to the attention of Gabriel Prosser, a slave who in 1800 attempted an unsuccessful revolt in northern Henrico County and Richmond. Supposedly, his plans included wiping out as much of the area’s white population as possible, but according to local legend, Mary Randolph would have been spared to serve as Prosser’s queen — and his cook! Perhaps this is when she acquired the nickname, “Queen Molly,” by which she was affectionately known to her friends.

Thomas Jefferson’s election to the presidency in 1800 marked the end of David Meade Randolph’s career as federal marshal. The two men were on opposite sides of the political fence and Jefferson removed Randolph from office immediately after his inauguration. This, along with business reversals, caused a rapid decline in the Randolphs’ fortunes and by 1802, they had listed Moldavia for sale.

Within a few years, their financial situation had become critical, and Mary stepped in. She was determined to see her family taken care of, and took what was then a highly unorthodox step for an upperclass woman. In March, 1808, an advertisement appeared in The Richmond Virginia Gazette: “Mrs. RANDOLPH Has established a Boarding House in Cary Street, for the accommodation of Ladies and Gentlemen. She has comfortable chambers, and a stable well supplied for a few Horses.” Putting her abilities as a hostess together with her knowledge of good food and elegant presentation, Mary achieved instant success. The Randolphs’ boarding house was considered a place where “wit, humor, and good-fellowship prevailed, but excess rarely.”

By 1819, the Randolphs had given up their business enterprise and moved to Washington, where they lived with one of their sons. There, Mary Randolph decided to compile her culinary knowledge to paper, and in 1824, her book, The Virginia Housewife, was published. It won immediate success: a second addition followed within a year, and Mary was preparing yet another when she died in January, 1828.

With Mary’s advanced culinary knowledge, her splendid recipes, and detailed advice to housewives, the book remained a standby, going into many editions throughout the 19th century. It continues to appear in facsimile even today.

While The Virginia Housewife is seen by some as a quaint reminder of culinary traditions long gone by, the book is viewed by today’s social historians as an important historical document in which dining habits of the Virginia elite can be examined. As noted culinary historian, Karen Hess, wrote, “The most influential American cookbook of the 19th century was The Virginia Housewife … There are those who regard it as the finest book ever to have come out of the American kitchen, and a case may be made for considering it to be the earliest full-blown American cookbook. [it] may be said to document the cookery of the early days of our republic.”

Chesterfield County can take pride in claiming Mary Randolph as a native daughter, an exemplary woman, and role model. Her courage and determination, her willingness to step off her pedestal to see that her family survived, and her ability to plunge into the world of business, mark her as a pioneer and role model to those who followed.

She wrote “The Virginia Housewife,” considered to be the first cookbook publoiched in America:

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard