Larry Francis Lucas was born on April 29, 1940 and joined the Armed Forces while in Marmet, West Virginia.

He served in the United States Army, 131 Aviation Company, 223 Aviation Battalion 17 AVN G. In 4 years of service, he attained the rank of Captain.

Larry Francis Lucas is listed as Missing in Action.

Sunday, January 19, 2003

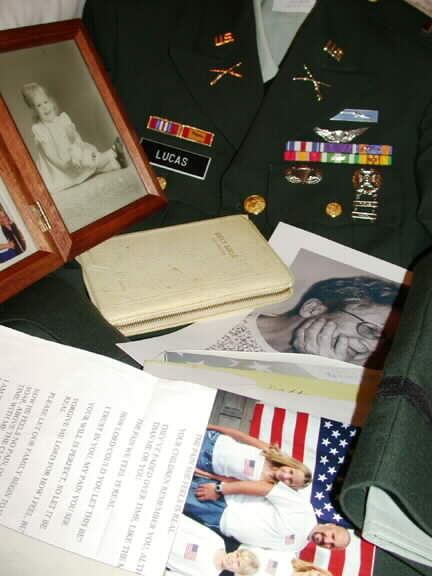

Strong emotions overcome Snyder Junior High history teacher Mike Holmes as he talks Wednesday about his uncle, Army Capt. Larry F. Lucas. Lucas was shot down over Laos during the Vietnam War, but his remains were not found until 1999.

BY JOHN REYNOLDS

AVALANCHE-JOURNAL

While growing up, Mike Holmes idolized his uncle, Larry Lucas.

He tagged along on dates while Lucas was courting his future wife, Martha. He also went on camping trips with Lucas — only 10 years Holmes’ senior — in the wilderness of their native West Virginia.

And, after Captain Lucas was shot down while on a reconnaissance flight over the jungles of Laos in the winter of 1966, Holmes kept the memory of his beloved uncle alive by telling history students about him.

Thus, when Lucas’ family learned in August his remains had been found, they chose Holmes to escort his uncle’s remains to military memorial services in San Diego, California, on October 26 and in Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia on November 1.

Holmes called the trip, which began when he received Lucas’ remains in Hawaii on October 23, “absolutely the greatest honor afforded me my entire life.”

Holmes has taught at Snyder Junior High School for 12 years. Before that, he taught at Ira and Amarillo, he said.

He began using Lucas in his lessons about Vietnam because the history books virtually ignored the Vietnam War, he said.

So the Vietnam War veteran created his own curriculum on the war with Lucas’ story as the emotional fulcrum. He usually gives the talk on Veterans Day or Memorial Day.

“In fact, our principal frequently says, ‘You’ve been telling your uncle’s story because (students) are coming out of class with tears streaming down their faces,’ ” Holmes said.

Lucas’ widow, Martha Lucas-Ryan, said it was Holmes’ unflagging devotion to her late husband’s memory that made her ask him to accompany Lucas’ remains and to eulogize him at the California memorial.

“You know, when the rest of the world seemed to forget him, Mike kept his memory alive,” she said. “To me, he was the best person in the world to deliver the eulogy.”

From the reaction to Holmes’ tribute, she knew she hadn’t erred in her choice.

“At the service in California, it was mostly people who did not know (Lucas),” she said. “But, because of Mike’s eulogy, they came up and said, ‘We feel like we know him.’ ”

Reaching for ejection lever U.S. Army Captain Larry Francis Lucas took off from the Phu Bai airfield in an OV-1 Mohawk aircraft the morning of December 20, 1966, according to a biography posted online by Task Force Omega, a Glendale, Ariz.-based organization dedicated to the rescue of POWs and MIAs.

His mission that morning was to reconnoiter the Ho Chi Minh trail, which was a notorious supply trail for the North Vietnamese.

About 10:20 a.m., Lucas’ aircraft was hit in an engine by anti-aircraft fire, causing the engine to burst into flames.

Holmes said he believed the fire burned through the hydraulics system, causing the aircraft to go into a 30-degree dive.

Lucas then ordered his co-pilot, Captain Joseph Kulmayer, to eject.

By that time, the plane was in such bad shape that “Joe went out horizontal and landed in some trees,” Lucas-Ryan said.

Kulmayer, who was found about an hour later, told rescuers he saw Lucas reaching for the ejection lever, Holmes said.

However, as soon as Kulmayer ejected, the plane went into a 90-degree dive and exploded on impact, Holmes said.

According to Task Force Omega, the Mohawk was consumed in the ensuing fire. The military declared Lucas “Killed In Action/Remains Not Recovered.”

Over the next 23 years, Lucas-Ryan, who lives in San Diego, said she received little information about her husband.

The first glimmer of hope arrived with an incident of extreme happenstance, according to Lucas-Ryan.

In late 1989, an interpreter reported seeing U.S. military dog tags on a villager in Laos. The U.S. government later sent an archaeological team to the village.

They found a crash site, but a dig failed to reveal remains, Lucas-Ryan said.

However, the government persisted and, in 1999, sent a team back to the village to follow up on a second tip that Lucas’ remains were there.

This time, the excavators widened their search perimeter and were able to locate bone fragments and personal effects they believed were Lucas’, his widow said.

The fragments were too small to provide a DNA match, but the government ascertained the remains were of Lucas by analyzing artifacts at the crash site, such as parts of a flight suit, a first-aid kit and a watch.

Lucas-Ryan said she was positive the remains brought home were of her late husband.

She hoped her story might comfort the almost 2,000 families whose loved ones remain missing in Southeast Asia, she said.

“If they know that someone who was lost 36 years was found,” she said, “it’ll give them hope.”

Lucas’ homecoming also afforded closure for his co-pilot, who attended the Arlington service with his wife and children. Afterward, they met with Holmes and Lucas’ family.

Holmes described the meeting as the most emotional event of his escort duty.

“I nearly collapsed,” he said. “It was the most phenomenal experience I’ve ever had.”

The group sat in an officer’s room and listened as Kulmayer related, over the course of two hours, exactly what happened that morning, Lucas-Ryan said.

“He told us such minute details about that event,” Holmes said.

Kulmayer’s wife later told Lucas-Ryan that that was the first time he’d talked about the crash.

“She told me he had been tormented all these years,” Lucas-Ryan said, as to why Lucas didn’t eject.

Holmes is convinced Lucas was waiting to make sure his co-pilot got away safely before rescuing himself.

Holmes also recounted meeting more Vietnam veterans at the memorial services who felt they owed their lives to Lucas.

“A lot of them served in Laos,” Holmes said. Lucas’ work as a reconnaissance pilot “literally enabled them to do their job.”

“They told me, ‘We’re alive because of what he did,’ ” Holmes said in a halting, teary voice.

Martha Lucas had been preparing to go to Hawaii when she received word that her husband had died.

“We were supposed to meet (there) on Christmas Day,” Lucas-Ryan said. “I had my suitcases packed.”

In fact, the colonel who was charged with delivering the bad news was ordered to show up at her door at 4 a.m. — two hours before the notification hour mandated by the military.

“He was told to get there early to make sure I hadn’t left,” she said.

She said military officials told her later they did not want to have to track her down and deliver the news at the airport, she said.

So, the colonel “waited outside my door in the dark for two hours,” she said.

At the time, Lucas had served seven months in Southeast Asia and was overdue for rest and recreation leave by a month, she said.

Letters from Lucas, who wrote his wife every day, continued to arrive for about two weeks after his death, she said.

In the letters, “he was anxious, excited, thrilled that we would see each other,” she said.

Later, when the military sent her husband’s personal effects, she opened his briefcase and found his leave orders on the top of his papers, she said.

She didn’t open the briefcase again until August, she said.

Holmes felt it was no coincidence that he met his uncle’s remains in Hawaii.

After all, Lucas was supposed to fly to Hawaii 36 years ago, Holmes said. When Lucas finally arrived, it was a family reunion that had simply been postponed.

Scared but anxious to serve

When asked why he talks about Lucas to his students, Holmes replied that he does it for two reasons, to enhance patriotism and make history relevant.

Thirty years removed from the Vietnam peace accords, students these days exhibit a lack of understanding about the Vietnam War, Holmes said.

“What’s disturbing is a lack of knowledge and a lack of patriotism,” he said. “My major objective is to try to build some level of patriotism in young people.”

By learning about Lucas, Holmes’ students see that “history is just common people like me doing what was needed to be done,” Holmes said.

After the Gulf War, Snyder honored the veterans of that conflict. Holmes said he remembered the words of a former student who had seen combat as a Marine.

“He was speaking and he said, ‘The reason I did what I did in the Persian Gulf was because of what the men in Vietnam did,’ ” Holmes said.

Recently, Holmes answered a knock on his classroom door and found a former student standing there.

Holmes was not pleased because “this guy was a horrible student,” he said.

However, his student had important news to tell: he had enlisted in the Navy.

“He said, ‘I know you thought I never heard a word (in class), but I heard it all,’ ” Holmes related.

The student then said, “Mr. Holmes, I want you to know I’m scared but I’m anxious to serve,” Holmes said.

“That’s what makes teaching worthwhile,” he said.

From a contemporary press report:

ASHLAND — It’s been 36 years since Martha Ryan’s husband died in Vietnam, but he’s finally getting a hero’s burial.

On November 1, 2002, U.S. Army Captain Larry Lucas will be laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery.

The ceremony will retire an old debt, Ryan said: “I always thought we never gave him his due. He deserved this and he never got it.”

Lucas, a Boyd County native, was a 26-year-old pilot flying reconnaissance missions over Laos when his plane was shot down in December 1966.

His remains were recovered three years ago in a field being cleared for use as a rice paddy.

Ryan and her daughter Melissa Condit, who was 4 the last time she saw her dad, were in Ashland Friday for the funeral service of Lucas’ mother, Jessie, who died September 5 in Southern California, where Ryan and Condit also live. Much of the family still live here and in West Virginia.

Ryan has never held any false hope that Lucas made it through the crash. A following plane saw it on fire and watched it go down vertically.

Witnesses in that plane saw only one parachute, and that belonged to the co-pilot, Captain Joseph Kuhlmayer. Kuhlmayer said Lucas ordered him to eject first, adhering to military procedure even in the blazing hell of the burning cockpit.

When Kuhlmayer left the aircraft the last thing he saw was Lucas with his hand on the ejection mechanism.

“He did his duty. Everybody says he died doing what he loved,” Ryan said.

Included in a package of personal belongings the military sent Ryan was a letter her husband had written. It told her that if she was reading it, Lucas must be dead. The letter suggested that she get on with her life and be grateful for the years they’d had together.

“I was grateful. We were childhood sweethearts and I was very happily married. He was the only boyfriend I ever had. He gave me the strength to have a new life,” she said.

She remarried and settled down in California to raise her children.

There was an investigation and a legal declaration of Lucas’ death, but that was largely to clear the way for insurance and military benefits.

The release in 1975 of American prisoners of war was traumatic because it first raised and then dashed vestigial hopes of his survival.

“I had to look every one of them in the face getting off the airplane. You always think, what if,” Ryan said.

In 1990 some doctors operating a clinic in Laos saw a villager with a set of dog tags. The tags belonged to Lucas. The villager showed the doctors where he’d found the tags, in a field being cleared for use as a rice paddy.

They saw plane parts. Villagers told them they’d discovered the wreckage some three years previously. Much of what had been on the site had been scavenged, so when a forensic team arrived, there was little to be seen.

The team found Lucas’ watch and camera and bits of gear a pilot would carry. They found no remains.

Several years later, an expanded search by another team revealed bone fragments. DNA testing was inconclusive, but the preponderance of evidence was enough for Ryan.

“We accepted it without any doubt,” she said.

Lucas had been studying forestry in college when the ROTC classes he took convinced him to pursue a military career. Always a risk-taker, he chose the most dangerous paths possible in the Army — flight school, Ranger school, combat duty.

That’s why although his family could have had him buried closer to their California home, they chose Arlington.

“All those old-time Army fighting spirits are there,” Ryan said.

The ceremony will be an avenue for the grief they never really expressed in the years after the crash, Condit said.

“There are things we didn’t know then. Now we know how important grieving is. We never did grieve. We have a chance to now.”

Condit is a member of an organization of people who lost their parents in war, most of them in Vietnam. She has been glad to report the finding of her father’s remains to members of that group, who take comfort in knowing the government’s considerable resources are still being devoted to finding and bringing home Americans killed in action, she said.

LUCAS, LARRY FRANCIS

Remains Returned 09/20/99 ID 04/26/2002

Name: Larry Francis Lucas

Rank/Branch: O3/US Army

Unit: 131st Aviation Company, 223rd Aviation Battalion, 17th Aviation Group

Date of Birth: 29 April 1940 (Ashland KY)

Home City of Record: Marmet WV

Loss Date: 20 December 1966

Country of Loss: Laos (officially listed in S.Vietnam)

Loss Coordinates: 164139N 1061451E (XD330460)

Status (in 1973): Killed/Body Not Recovered

Category: 3

Acft/Vehicle/Ground: OV1A

Refno: 0553

Other Personnel In Incident: Captain Joseph L. Kulmayer (rescued)

Source: Compiled from one or more of the following: raw data from U.S. Government agency sources, correspondence with POW/MIA families, published sources, interviews. Updated by the P.O.W. NETWORK in 2002.

SYNOPSIS:

On December 20, 1966, Captain Larry F. Lucas, pilot; and Captain Joseph L. Kulmayer, co-pilot, flew an OV1A Mohawk (serial #63-13123) out of Hue’s Phu Bai airbase on a reconnaissance mission over Laos in an operations region known as “Foxtrot”. Their plane was hit by enemy fire, caught fire, pitched into a ninety degree dive and crashed. Capt. Kulmayer ejected and was later rescued. No sign of any other parachute was seen.

Although Lucas’ parachute was not seen, Captain Kulmayer stated that at the time of his own ejection, he saw Capt. Lucas’ hand on the overhead canopy release handle.

The last known location of the plane was near Sepone, Laos, about 25 miles from the border of South Vietnam. Defense department records list Lucas as missing in South Vietnam, although the loss coordinates are clearly in Laos. Why Lucas is not listed missing in Laos is unknown.

The OV1A was outfitted with photo equipment for aerial photo reconnaissance.

The planes obtained aerial views of small targets – hill masses, road junctions, or hamlets – in the kind of detail needed by ground commanders. The planes were generally unarmed. The OV1’s were especially useful in reconnoitering the Ho Chi Minh trail.

Lucas is among nearly 2500 Americans who did not come home from Southeast Asia at the end of the war. Unlike the MIAs of other wars, many of these men can be accounted for. Tragically, nearly 6000 reports of Americans still in captivity in Southeast Asia have been received by the U.S., yet freedom for them seems beyond our grasp.

NOTE: The 20th Aviation Detachment existed until December 1966, at which time it was reassigned as the 131st Aviation Company, 223rd Aviation Battalion (Combat Support). The 131st Aviation Company had been assigned to I Corps Aviation Battalion since June 1966, when it arrived in Vietnam. In August 1967, the 131st Aviation Company was reassigned to the 212th Aviation Battalion where it remained until July 1971, whereupon it transferred out of Vietnam.

There were a large number of pilots lost from this unit, including Thaddeus E. Williams and James P. Schimberg (January 9, 1966); John M. Nash and Glenn D. McElroy (March 15, 1966); James W. Gates and John W. Lafayette (April 6, 1966); Robert G. Nopp and Marshall Kipina (July 14, 1966); Jimmy M. Brasher and Robert E. Pittman (September 28, 1966); James M. Johnstone and James L. Whited (November 19, 1966); Larry F. Lucas (December 20, 1966); and Jack W. Brunson and Clinton A. Musil (May 31, 1971). Missing OV1 aircraft crew from the 20th/131st represent well over half of those lost on OV1 aircraft during the war.

U.S. Army records list both Nopp and Kipina as part of the “131st Aviation Company, 14th Aviation Battalion”, yet according to “Order of Battle” by Shelby Stanton, a widely recognized military source, this company was never assigned to the 14th Aviation Battalion. The 131st was known as “Nighthawks”, and was a surveillance aircraft company.

Vietnam Pilot’s Family Thanks Military For Remains

Thursday Oct 24, 2002

Relatives of an Army pilot who perished in a Laos plane crash during the Vietnam War thanked the U.S. military Wednesday for tracking down his remains and arranging for an honored serviceman’s burial after 36 years.

Captain Larry Francis Lucas’ daughter, Melissa Lucas-Condit of San Marcos, spoke to reporters at Marine Corps Air Station Miramar about her family’s gratitude at the end of a decades-long ordeal.

Her voice faltering, she described her and her siblings’ “troubling passage from happy children with a brave father to confused kids, wondering why Daddy never came home.”

Investigators found the wreckage of Lucas’ OV-1A Mohawk reconnaissance aircraft in a remote jungle four years ago. Equipment, personal items and bone fragments inside it proved to be those of the long-missing flier.

His daughter praised the government’s persistence in providing closure for her family, most of whom live in the San Diego area.

“All those men and women who stuck it out and excavated those fragments of (his) airplane, flight suit, survival kit, camera and wristwatch all knew those bits and pieces would breathe some margin of life back into him so he could take his final flight back home,” she said.

Lucas’ mother died last month, soon after Army officials told her they had identified her son’s remains.

“I think she stayed on until she knew they had found him,” Lucas-Condit told the San Diego Union-Tribune earlier this week.

Lucas was one of 2,583 U.S. soldiers, Marines, sailors and airmen unaccounted for after the Indochina war ended.

He and Captain Joe Kulmayer were looking for enemy infiltrators over the Ho Chi Minh Trail, the North Vietnamese army’s main supply route into South Vietnam, when enemy fire downed their two-seater on December 20, 1966.

Only Kulmayer managed to eject before the plane crashed. Unable to locate Lucas, the Army declared him killed in action.

His remains were unaccounted for until 1989, when a physician in Laos noticed a villager wearing his dog tags.

Using that information, searchers in 1998 found the site where Lucas’ plane went down.

They turned the bone fragments over to military forensics experts at Honolulu’s Central Identification Laboratory, who concluded earlier this year that they were those of the presumed-dead pilot.

Lucas’ family will take part in a memorial service at Vista Wesleyan Church on Saturday. Interment with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery is set for November 1, 2002.

LUCAS, LARRY FRANCIS

CAPT US ARMY

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: 12/01/1960 – 12/20/1966

- DATE OF BIRTH: 04/29/1940

- DATE OF DEATH: 12/20/1966

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 11/01/2002

- BURIED AT: SECTION 67 SITE 4289-2

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard