From a contemporary press report:

Finding closure

Courtesy of Blethen Maine Newspapers Inc.

NEW VINEYARD — Deep in the thick jungles of Papua New Guinea in the South Pacific, on a precipitous peak in the Finisterre Range, a World War II B-25 bomber and its occupants were hidden for more than 50 years.

Ginny Park was 14 in 1944 when she watched her older brother, Henry Miga, go off to war. Miga was 28, and he followed Park’s other two brothers into combat. They returned, but Henry did not — until recently.

On May 6, 2001, Park, along with her sister, Julia McCarthy, and brother-in-law; her daughter, Barbara Toner of Fairfield; and several nieces and nephews was invited, at the military’s expense, to Arlington National Cemetery in Washington, D.C. It was there, at the Old Post Chapel, that they attended an interment service with full military honors for Sergeant Henry Miga and seven fellow soldiers who were lost in World War II.

“At first I didn’t believe it,” Park said, about the letter she received in 1999 from Alfred Hagen, which stated he had found the plane and Miga’s remains.

“My brother had been declared missing in action on July 1, 1944, and after not finding the plane, the military declared the entire crew dead on July 1, 1945. But after we contacted (Hagen), my sister and I just went, ‘Wow.’ ”

Alfred Hagen first began his search for soldiers missing in action in 1995 when he set out to locate an uncle who was lost during World War II. After finding his uncle’s plane, he made it a life mission to find others.

On his fourth trip to New Guinea, he made a fortuitous stop at a local village, where he learned of two more crash sites. Jumping from a helicopter into a bed of smoldering ash, Hagen attempted to reach the first crash site.

Because of to heavy smoke from forest fires and a destroyed camera, he did not complete filming the mission until June 1998. At mission’s end, however, he had found the B-25 carrying the remains of gunner Henry Miga and eight other soldiers.

The plane, identified by its serial number, was traveling to Nadzab, in what was then known as New Guinea, on an undisclosed mission, with seven Army Air Corps men and two passengers going on leave. It crashed into a treacherous peak at 10,000 feet. Hagen found the plane’s wreckage flowing down the gully, along with the remains of the fliers.

It was last month before Park and her family heard anything further about her brother. The military notified each family by letter of the planned honors for the identified soldiers.

“It was a beautiful ceremony. It really was,” said Park, recalling the service at Arlington.

A memorial service at Old Post Chapel was followed by a caisson carrying the coffin of one of the corpsmen, pulled by eight horses. A procession of hearses and limousines trailed the caisson through the cemetery to the grave site.

The eight coffins were lined up among a sea of headstones overlooking Washington, D.C., each with an honor guard holding an open flag above it. “Taps” was played, followed by a three-gun salute, and then the soldiers were finally laid to rest under cloudless sky and brilliant sun — a perfect day.

It had been 60 years since the men had been declared missing and, according to Park, for many of the people who attended the service, it brought closure.

“I only wish that my other two brothers had lived to be there. The three boys were very close,” Park said. For Park, despite her young age at the time, it brought back many memories. “What I remember most about my brother is that he was very good to my mother.”

A draftsman by trade, Miga “loved his car and the Red Sox. I can remember he and his friends washing their cars and listening to the ball game. Boys treasured their cars then,” Park said.

“He would have been 88 now, if he had lived.”

Park was pleased her brother was buried in Arlington and was finally getting the military honors he deserved. When asked how she felt about the event, Park said, “Well, it was really nice. I feel patriotic again.”

Patriotism and military service were important to Park’s late husband and continue to factor in Park’s life.

At the start of the Korean War, Park was a registered nurse. She gave up private duty to join the Navy nurses, and she attained the rank of ensign. “I feel I was treated well, and got a lot of respect in the military,” Park said.

Her husband, Joe, a West Point graduate, rose to the rank of colonel before he retired. He came from an extensive military family.

“It was inborn in him,” Park said. “Joe’s mother and father are buried in Arlington, too.” It is perhaps fitting that Park lives on Herrick Mountain Road, once locally called Military Hill.

Park was at first reluctant to tell her story, but she decided to go forward.

“In view of all the (negative) stuff that is in the paper these days (regarding the military), maybe someone will find my story uplifting,” she said.

Click Here For Additional Information

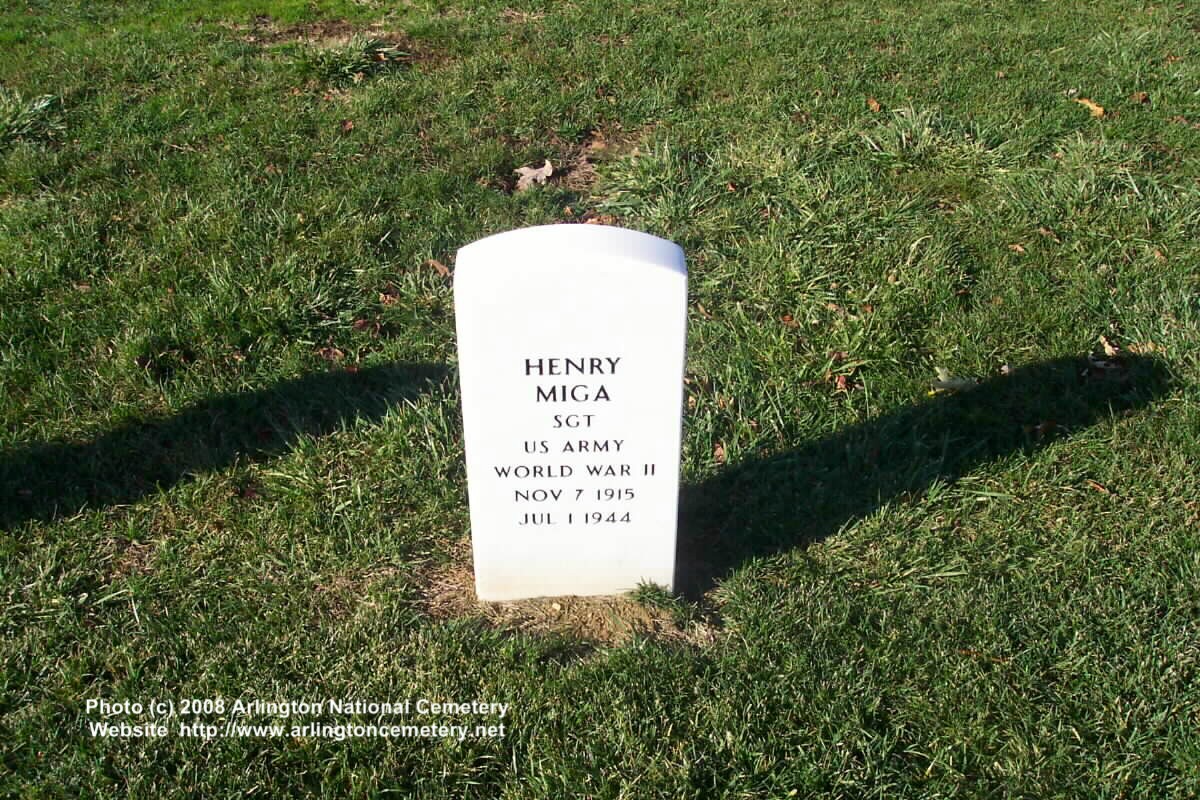

MIGA, HENRY

SGT US ARMY

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: 03/19/1943 – 07/01/1944

- DATE OF BIRTH: 11/07/1915

- DATE OF DEATH: 07/01/1944

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 05/06/2004

- BURIED AT: SECTION 60 SITE 7946

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

MIGA, HENRY

SGT US ARMY

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: 03/19/1943 – 07/01/1944

- DATE OF BIRTH: 11/07/1915

- DATE OF DEATH: 07/01/1944

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 05/06/2004

- BURIED AT: SECTION 60 SITE 7950

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard