Born at Boston, Massachusetts, November 20, 1925, he served as a Seaman Second Class (SN2) in the United States Navy during World War II.

He was campaign manager for John F. Kennedy when he sought the Presidency in 1960. He served as Attorney General in his brother’s administration from January 1961 until his resignation on September 3, 1964, to become a candidate for the United States Senate from New York.

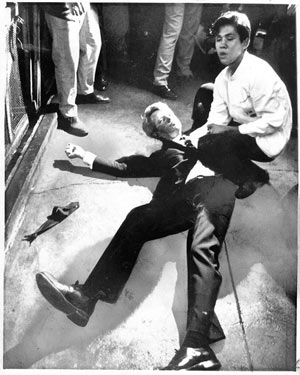

He was elected as a Democrat and served from January 3, 1965 until his death. He died from the effects of an assassin’s bullets on June 6, 1968 at Los Angeles, California while campaigning for the Democratic nomination for President of the United States.

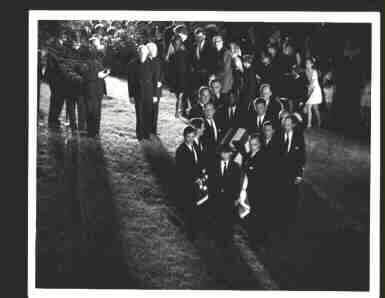

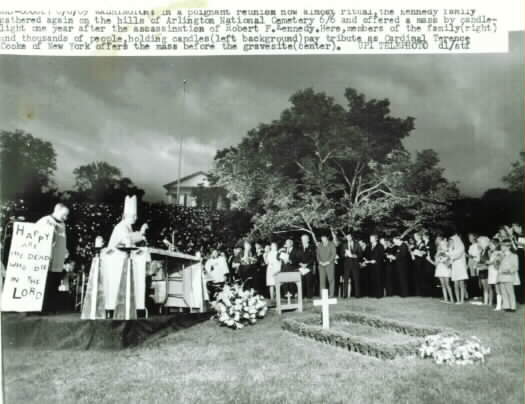

He was buried in Section 45 of Arlington National Cemetery, just steps from his brother’s gravesite, in a very rare night burial.

On June 8th, 1968, the day of Bobby’s funeral, another Kennedy brother, U.S. Senator Edward Kennedy, eulogized:

“My brother need not be idealized, or enlarged in death beyond what he was in life, to be remembered simply as a good decent man, who saw wrong and tried to right it, saw suffering and tried to heal it, saw war and tried to stop it.

“Those of us, who loved him and who take him to his rest today pray that what he was to us and what he wished for others will someday come to pass for all the world.

“As he said many times, in many parts of this nation, to those he touched and who sought to touch him: ‘Some men see things as they are and say why. I dream things that never were and say why not.'”

November 20, 2001

Bush Renames Justice Building in Honor of Robert F. Kennedy

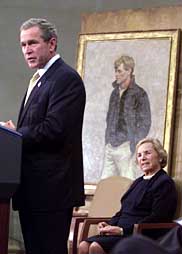

In a ceremony rich with poignant memories and political twists, President Bush renamed the Justice Department building today in honor of Robert F. Kennedy, who served as attorney general from 1961 to 1964.

“Robert Kennedy was not a hard man, but he was a tough man,” Mr. Bush said on what would have been Robert Kennedy’s 76th birthday. And while he was not the longest serving head of the Justice Department, “few have filled their term here with so much energy,” the president said.

Mr. Bush and Attorney General John D. Ashcroft said Kennedy’s non compromising battles against racial injustice and organized crime exemplified what an attorney general should be.

“To millions who never knew him,” Mr. Bush said, “he’s still an example of kindness and courage.”

The renaming of the Justice Department headquarters was accomplished by Mr. Bush’s executive order. But Mr. Ashcroft said today’s event was much more than a renaming. “We are rededicating the Justice Department to the cause he served,” Mr. Ashcroft said.

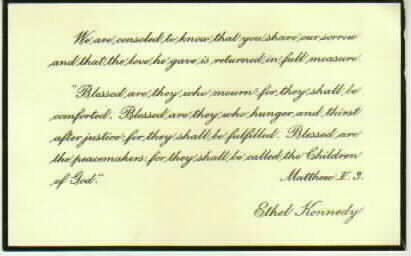

Robert Kennedy’s widow, Ethel, sat near Mr. Bush and Mr. Ashcroft and was warmly embraced by the president. Senator Edward M. Kennedy of Massachusetts was there, along with various other members of the Kennedy clan. Several former attorneys general also attended.

Joseph P. Kennedy 2nd, one of Robert Kennedy’s 11 children, said his father was “tough, smart, utterly unafraid” and, yes, stubborn at times.

“He forced every American to look into his heart and see what was right — and do something about it,” he said.

A former congressman with hair whiter than his father’s ever was, Joseph Kennedy is 49, or seven years older than his father’s age in 1968, when he was a senator from New York and seeking the Democratic presidential nomination. He was shot to death on June 5, 1968, after winning the California primary.

Today’s ceremony bridged partisan divides. Joseph Kennedy warmly thanked the Republican president for honoring his father and said, “Your strength since Sept. 11 has been a profile in leadership.”

Mr. Ashcroft said Robert Kennedy was a man who embraced “causes, struggles, principles that transcend us.” Kennedy was a man who wanted “justice for all Americans,” Mr. Ashcroft said. “He was unafraid of calling his enemies evil.”

In an odd coincidence, the Justice Department ceremony came a few hours after one at which Robert Kennedy’s daughter Kerry Cuomo criticized the Bush administration for giving broad new powers to the police and prosecutors to fight terrorism.

Ms. Cuomo, who is married to Andrew Cuomo, the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development under President Bill Clinton, spoke at an event honoring Darci Frigo, a Brazilian lawyer and land-reform advocate who won this year’s Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Award.

Addressing her daughter Cara, Ms. Cuomo said, “Cara, if anyone tries to tell you this is the type of justice your grandpa would embrace, don’t you believe it.”

In his time, Robert Kennedy was seen by his critics as driven and vindictive, willing to do almost anything in pursuit of his enemies. To his admirers, he was viewed as a man and politician committed to helping the poor and stamping out injustice — a man who embraced causes “worth the passion of life,” as Mr. Ashcroft put it.

Mr. Ashcroft, in fact, has defended the Bush administration’s arrest-and-detention tactics and, to justify them, has invoked memories of the crime-fighting approach of an earlier attorney general — Robert Kennedy.

Before today’s Justice Department ceremony, several members of the Kennedy family went to Arlington National Cemetery, just across the Potomac River in Virginia. Robert Kennedy’s grave is near that of his brother, President John F. Kennedy, who was assassinated 38 years ago this Thursday.

Kneeling again next to RFK

By Steve Lopez

Courtesy of The Los Angeles Times

November 21, 2010

In 1968, 17-year-old busboy Juan Romero held Robert Kennedy’s hand as the senator lay dying at the Ambassador Hotel. On what would have been RFK’s 85th birthday, Romero visits his grave at Arlington National Cemetery.

By Steve Lopez

As a skinny teenage busboy, Juan Romero knelt beside a mortally wounded Bobby Kennedy at the Ambassador Hotel. On Saturday morning, more than 42 years later, he knelt again, this time beside RFK’s grave on what would have been Kennedy’s 85th birthday.

Romero was wearing a suit for the first time in his life, saying it was the proper way to show his respect for a man whose memory he has tried to honor by living a life of tolerance and humility.

Getting up the courage to visit Arlington National Cemetery was not easy for Romero, a construction worker from San Jose who has been haunted for decades by the events of June 5, 1968. Under a soft blue sky, with fall colors exploding across the velvety slopes of the cemetery, Romero walked off to be alone and have one last good cry before visiting the grave.

“Sorry,” he apologized to his daughter, Elda, and friend, Rigo Chacon, who had made the trip with him from California. “If I can get it out of the way now….” Maybe a good cry would help him keep his composure, he said, when he finally stood at the grave.

I first wrote about Romero in 1998, on the 30th anniversary of the RFK assassination, and was struck by his decency and spirit of goodwill. For years, he had avoided talking about his small part in a national tragedy, but he came to believe it was his duty to speak up about his own take on Kennedy’s legacy, in part because hatred and small-mindedness often pollute the national conversation.

Romero’s family moved to California from Mexico when he was 10. He lived in projects for a while and might have gotten caught up in the gang life except that his stepfather yanked him out of that world and helped get him a job at the Ambassador Hotel.

When Kennedy called for room service a few nights before the California primary, Romero paid off another busboy for the privilege of delivering his food. Even though he was just 17, Romero knew that RFK was a man of empathy who had walked with Cesar Chavez, and he felt more accepted as an immigrant — more American — just knowing that Kennedy might become president.

When Kennedy shook Romero’s hand, in the presidential suite, Juan was transformed. In that firm grip, he felt appreciated, he felt whole, he felt like a man. Two nights later, when Kennedy won the primary, Juan raced to the Ambassador pantry and shook RFK’s hand again as the candidate went to deliver his victory speech.

After the speech, Romero pressed through the crowd again, his pride swelling. Once more, he shook Kennedy’s hand. And then came the gunshot. Four and a half years after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, and two months after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Bobby lay dying from an assassin’s bullet.

He was shot while holding Romero’s hand.

At Arlington on Saturday, Romero, now 60, walked slowly. His chest was tight and his shoulders stiff as he made his way toward the simple, small white cross that marks RFK’s grave. He had wept the night before as he anticipated this moment, telling me how he had refused to wash Kennedy’s dried blood off his hand.

On the day after the shooting, as he was sitting on the bus on the way to Roosevelt High, a woman, reading the Los Angeles Times, looked at a picture in the paper of a young busboy in a crisp white uniform, a mask of disbelief on his face as he tried to help Kennedy up off the floor.

“This is you,” the woman said to him, and Romero looked away in horror.

Forty-two years later, as Romero approached the grave, his friend Chacon stood at a respectful distance, knowing Romero had to do this in his own way. Chacon, a retired TV newsman, had seen Romero break down many times over the years as he relived the trauma. Chacon had finally suggested he visit Arlington for the sake of his own healing.

Romero holds himself at least partly responsible for Kennedy’s death, and in his private moment with Kennedy now, he wanted to ask forgiveness. If he hadn’t been so intent on shaking Kennedy’s hand, he told me, he might have seen and stopped the assassin. He would have taken the bullet himself, he said, if Kennedy could have been spared.

I told Romero it’s time he let go of the guilt. RFK, a man of peace, was killed by Sirhan Sirhan, a man of violence and rage. There’s no way to make sense of that, but I urged him to listen to his buddy, Chacon, who reminds him that in a moment of tragedy, Juan did a humane thing. He didn’t run, he didn’t take cover. He tried to help, thinking perhaps that Kennedy had merely been pushed out of harm’s way and hit his head on the concrete. When the young busboy realized the situation was grave, he took his own rosary beads out of his shirt pocket, twisted them around Kennedy’s hand and prayed for him.

On Saturday, Romero stood silently over the cross, his hands clasped, staring down at the small gravestone. He spoke softly, telling Kennedy how much he loved his country and tried to honor the ideals Kennedy preached.

Bobby Kennedy was a complicated man who had many critics on both the left and the right. But as Romero knelt at the grave and broke down once more, it was for the Kennedy he knew, the one whose words are engraved on a wall near his resting place:

“What we need in the United States is not division … not hatred … not violence or unlawfulness, but love and wisdom and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country…. Let us dedicate ourselves to what the Greeks wrote so many years ago: to take the savageness of man and make gentle the life of this world….”

Romero walked away from the grave with perhaps a small piece of his burden lifted. He briefly toured the graves of John and Ted Kennedy, guided by Rep. Mike Honda (D-San Jose) and Rep. Patrick Kennedy (D-R.I.), the son of Ted. Talking, however briefly, to a Kennedy about RFK’s commitment to social justice seemed to help Romero find some peace.

“It’s hard to say goodbye,” Romero said before leaving Arlington. But clearly he was pleased that he had knelt, once more, beside Bobby Kennedy. “I want him to know he’s remembered.”

“It is from numberless diverse acts of courage and belief that human history is shaped each time a man stands up for an ideal or acts to improve the lot of others or strikes out against injustice he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope, and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring those ripples build a current that can sweep down the mightiest wall of oppression and resistance.”

Robert F. Kennedy, South Africa, 1966

“Some men see things as they are and ask ‘Why?’

I dream things that never were and ask, ‘Why not?'”

Robert F. Kennedy, 1968

6 June 1968

OBITUARY

Robert Francis Kennedy: Attorney General,

Senator and Heir of the New Frontier

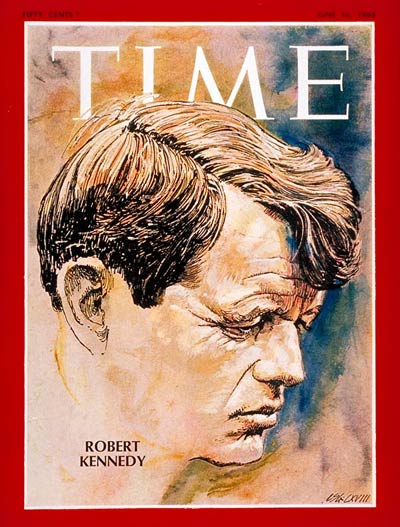

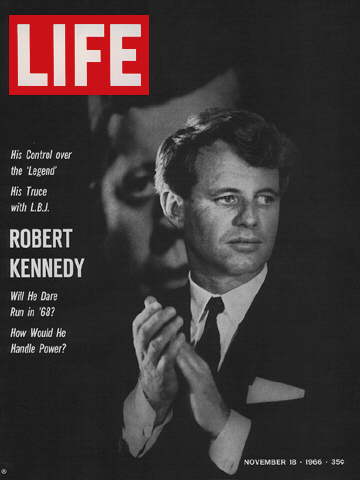

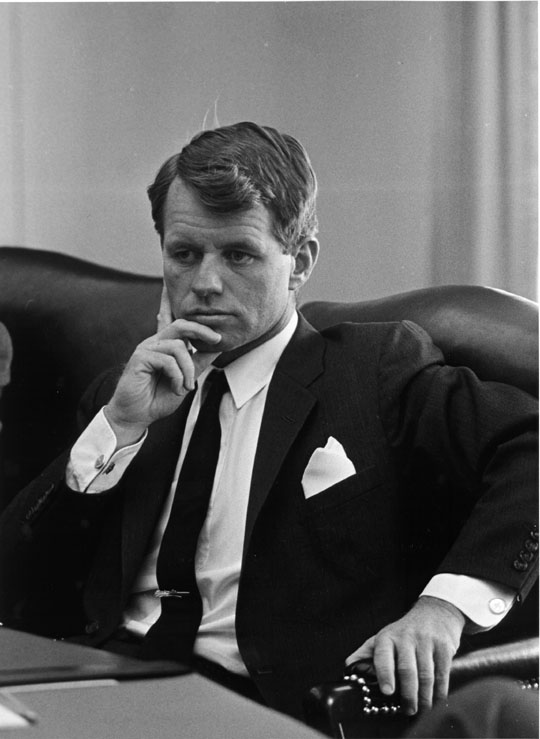

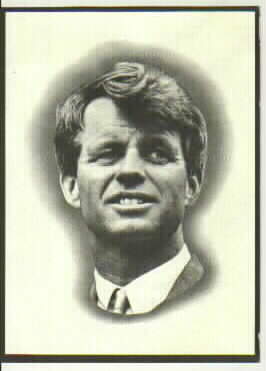

In his brief but extraordinary political career, the 42-year-old, Massachusetts-born Robert Francis Kennedy was Attorney General of the United States under two Presidents and Senator from New York. In those high offices he exerted an enormous influence on the nation’s domestic and foreign affairs, first as the closest confidant of his brother, President John F. Kennedy, and then, after Mr. Kennedy’s assassination in 1963, as the immediate heir to his New Frontier policies.

The Kennedy name, which John had made magical, devolved on Robert, enabling him to win a Senate seat from a state in which he had little or no previous association. The Kennedy aura also permitted him to campaign this year for the Democratic Presidential nomination and to gain important victories in the preference primaries. Wherever he went he drew crowds by evoking, through his Boston accent, his gestures and his physical appearance, a remarkable and nostalgic likeness to his elder brother.

At the same time Mr. Kennedy called forth sharply opposed evaluations of himself. For those who found him charming, brilliant and sincerely devoted to the welfare of his country there were others who vehemently asserted that he was calculating, overly ambitious and ruthless.

Those who praised him regarded his candidacy for his party’s Presidential nomination this year as proof of his selflessness. They quoted with approval his announcement on March 16, in which he said:

“I do not run for the Presidency merely to oppose any man but to propose new policies. I run because I am convinced that this country is on a perilous course and because I have such strong feelings about what must be done, and I feel that I’m obliged to do all I can.”

On the other hand, those who questioned his motives pointed out that his candidacy was posed only four days after the New Hampshire primary, in which Senator Eugene J. McCarthy had demonstrated the political vulnerability of President Johnson. Further, Mr. Kennedy’s critics said, he had declared only as recently as January 30:

“I have told friends and supporters who are urging me to run that I would not oppose President Johnson under any foreseeable circumstances.”

Sure He’d Do ‘the Right Thing’

Mr. Kennedy’s partisans tended to ignore his inconsistencies or to belittle them. And even many voters who expressed reservations about him were certain that, in public office, he would do “the right thing.” This belief was underlined, especially among Negroes and the poor, because of the earnestness with which he pleaded their cause.

Describing the reaction of one ghetto throng in California, Tom Wicker wrote in The New York Times of June 2:

“The crowds surge in alarmingly, children leap and shriek and grown men risk the wheels of Kennedy’s car just to pound his arm or grasp his hand. Moving through the sleazy back streets of Oakland, he repeatedly stopped traffic; for six blocks along East 14th Street, his car could barely creep along.”

Contrasting with such frenzied warmth was what Fortune magazine called last March “the implacable hostility toward him in the business community.” The magazine quoted one Dallas businessman, a leading Democrat, as saying:

“I had great respect for his brother Jack, but I would not vote for Bobby.”

The business community, according to Fortune, condemned Mr. Kennedy as immature and irresponsible. Business, it was said, was disquieted “by the reputation for radicalism that he has developed.”

To criticism he could respond with asperity or angry chilliness. To the fervor and adulation of his supporters he seemed curiously aloof, exhibiting neither pleasure nor fright. Those close to Mr. Kennedy noticed that his eyes rarely sparkled, but, instead, were sad and withdrawn and that his manner, despite a grin, was unemotional.

Mr. Kennedy’s campaign speeches (as well as those he delivered in the Senate) were, for the most part, devoid of oratorical fire and flourish. He spoke in an even baritone; there were no crescendos and little outward expansiveness. His only gestures were to chop the air with his right hand for emphasis or to brush back his shaggy forelock when it slipped down over his forehead.

His campaign humor was self-deprecating, an effort to divert criticism to his account. For example, he recently asked a rally in Fort Wayne, Indiana, whether the city would vote for him. Otherwise, he went on, he and Ethel and all of their children would have to go on relief. “It’ll be less expensive,” he continued, deadpan, “just to send us to the White House. We’ll arrange it so all 10 kids won’t be there at once, and we won’t need to expand the place. I’ll send some of them away to school — and I’ll make one of them Attorney General.”

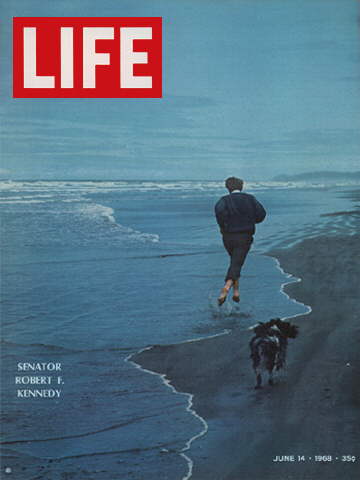

Mr. Kennedy was an indefatigable campaigner, able to put in a 16-hour day of stress and tension and then sleep briefly before going through another equally strenuous day. Indeed, he seldom seemed to relax, whether he was campaigning or not, for he played with as much concentration as he worked. He was, for instance, a vigorous touch football participant, a hardy skier, a pace-setting mountain climber and a swimmer who did not mind plunging into the cold Pacific surf on an Oregon beach, an exploit few in that state ever attempted.

Mr. Kennedy was so constantly in motion that he prompted some observers to say that he fled introspection, that he did not sit down with himself and figure out what he truly was and what he wanted to achieve. Commenting on this public and private extroversion in “The Heir Apparent,” William V. Shannon wrote in 1967:

“In his compulsive athleticism, his reckless risk-taking, his aggressiveness, he seems to be driven by something not accounted for by the realities which engage him and not compatible with the high seriousness of his public ambitions.”

‘You Have to Struggle’

Mr. Kennedy was, of course, aware of what was said about him, for he not only read omnivorously but he also employed a large staff of experts and advisers to brief and counsel him. He often conceded that he was aggressive, explaining semi humorously:

“I was the seventh of nine children. And when you come from that far down, you have to struggle to survive.”

Robert Kennedy was born Nov. 20, 1925, in Brookline, Massachusetts, a fashionable suburb of Boston, the son of Joseph and Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy. His father, the son of poor South Boston parents, was then already amassing a fortune in the stock market and associated speculative enterprises.

Home only at intervals (the family moved in 1926 to Riverdale and then to Bronxville, N.Y.), he left the day-to-day management of the family to his capable wife, who was the daughter of John F. (Honey Fitz) Fitzgerald, who served three terms in the House of Representatives and was Mayor of Boston.

When Robert was born, his brother Joseph Jr. was 10 and John was 8. (Edward was born in 1932.) Thus Robert passed his early years as the little brother, with two older brothers and five young sisters — Rosemary, Kathleen, Eunice, Patricia and Jean. “He was the smallest and thinnest, and we feared he might grow up puny and girlish,” his mother recalled, adding: “We soon realized there was no fear of that.”

Not only were Robert’s sisters tomboyish, but he was also prodded to competitiveness by his father and by Joseph Jr., who served as a surrogate father to his siblings.

“Joe taught me to sail, to swim, to play football and baseball,” he remembered. Moreover, Robert’s father laid down strict rules of conduct: Never take second best; when the going gets tough, the tough get going; passivity is intolerable.

Although Robert as a youth was overshadowed by his older brothers, he displayed grim determination to succeed. A classmate at Milton Academy, where he prepared for Harvard, said: “It was much tougher in school for him than the others — socially, in football, with studies.” Nonetheless, Robert kept up.

He was a Harvard sophomore when Joseph Jr., on whom the family had pinned its political hopes, was killed in a Navy plane over the English Channel in 1944. Deeply affected, Robert traveled to Washington on his own several months later and persuaded Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal to assign him as a seaman to a destroyer newly named for his brother.

Robert spent the remainder of the war in the Caribbean, returning to Harvard in 1946. There his tenacity gained him a place as end on the football team, although he weighed only 160 pounds and stood 5 feet 9 inches tall. After graduation in 1948, he went to law school at the University of Virginia, where he took his degree in 1951.

That same year, after admission to the Massachusetts bar, he joined the criminal division of the Department of Justice in Washington and spent two years prosecuting a somewhat dreary succession of graft and income tax evasion cases without notable splash.

Resigned to Run Campaign.

He resigned in 1952 to manage the campaign of his brother John for United States Senator from Massachusetts. The most impressive features of that race were the Kennedy organization’s painstaking attention to detail and the vast amount of money it spent. Both later became hallmarks of Robert Kennedy’s campaign methods.

Mr. Kennedy’s first (and ultimately most controversial) venture into the public limelight occurred in 1953, when he was named one of 15 assistant counsel to the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations.

His immediate superior was Roy M. Cohn, the group’s chief counsel. Above them both was Senator Joseph R. McCarthy, Republican of Wisconsin, whose name was soon attached to the committee. It rapidly acquired a malodorous reputation among liberals, intellectuals and civil libertarians for its chivvying of witnesses in its investigations of asserted Communist conspiracies and plots in the Government. Robert had obtained his job through his father, who had contributed money to Senator McCarthy’s anti-Communist campaign. He got along well with the Senator, a circumstance that plagued Mr. Kennedy when he became, years later, a professing liberal.

After a dispute with Mr. Cohn over the committee staff, Mr. Kennedy resigned his post in mid-1953, but rejoined it in February, 1954, as counsel to the Democratic minority. The following year — after the Army-McCarthy hearings — he succeeded Mr. Cohn as chief counsel and staff director when Senator John L. McClellan, Democrat of Arkansas, became committee chairman. In that post he pursued investigations into alleged Communist influence and helped develop some of the conflict-of-interest cases involving personalities in the Eisenhower Administration. Senator McClellan liked him, for he was a persistent questioner of witnesses and a resolute investigator.

One result was that the Senator chose Mr. Kennedy as chief counsel of the Senate Select committee on Improper Activities in the Labor or Management Field when it was organized in January, 1957. Mr. Kennedy immediately began a headline-making inquiry into the affairs of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, then under the presidency of Dave Beck. Beck was later imprisoned for filing false income tax returns.

Accused of Anti labor Views

Mr. Kennedy’s sharp questioning of Beck before the Senate Rackets Committee, as the McClellan group was generally known, drew down on him the accusation that he was anti labor at worst and unsympathetic to the working man at best. This charge was compounded when he investigated James R. Hoffa, Beck’s successor, in 1958.

Hoffa, who was eventually convicted and jailed for jury tampering and misuse of union funds, disliked Mr. Kennedy, calling him “a young, dim-witted, curly-headed smart-aleck” and “a ruthless monster.” Calm and polite as the committee’s counsel, Mr. Kennedy nevertheless did not conceal his disdain for Hoffa. His reaction to an involved and obscure answer was often a sarcastic and disbelieving: “Oh.”

Later, when he was Attorney General, Mr. Kennedy continued his investigation of the 1,700,000-member teamsters union, causing Hoffa to charge that he was engaged in vendetta. Officials of other unions were also prosecuted by Mr. Kennedy, generating a coolness of organized labor toward him that was still evident when he was campaigning for the Democratic Presidential nomination in 1968. The attitude of the trade union hierarchy, however, did not permeate to the rank and file, who generally voted for him.

Mr. Kennedy left the rackets committee in 1959 to manage his brother’s campaign for the Presidency. Describing the primary races of 1960, Lawrence J. Quirk, in “Robert Francis Kennedy,” wrote:

“Bobby kept his card file constantly replenished with information on every local leader, every county VIP, every ‘bit’ player in every key town. And he bore down most heavily on the states where the primary battles looked hottest: New Hampshire, Indiana, West Virginia and Wisconsin (already marked for the kill), Oregon and Nebraska.

“But Bobby’s strong-arm methods were not just limited to the states where the primaries were crucial. Gov. [Michael] Di Salle of Ohio, who had hoped to run as a favorite-son candidate, was soon finding himself unremittingly pressured by Bobby to endorse Jack Kennedy. The two little fighting words ‘or else’ hung in the air. With a primary fight against the Kennedys — a fight he stood to lose – a distinct possibility, Di Salle finally capitulated. ‘The Kennedys play rough and they play for keeps,’ he later said.”

As his brother’s vizier, Robert Kennedy never bothered to hide his political muscle in 1960. Answering one politician’s complaint, he said blandly:

“I’m not running a popularity contest. It doesn’t matter if they [the politicians] like me or not. Jack can be nice to them. I don’t try to antagonize people but somebody has to be able to say no. If people are not getting off their behinds and working enough, how do you say that nicely? Every time you make a decision in this business you make somebody mad.”

In the election campaign that followed, against Richard M. Nixon, the Republican candidate, Mr. Kennedy proved as drivingly perfectionist as he had been during the primary races. He traveled the country, tightening up the party organization, settling squabbles and dismissing incompetents. He even silenced Frank Sinatra, the singer, and Walter Reuther, head of the United Auto Workers, whom he considered liabilities to his brother.

In addition to these tasks, Mr. Kennedy advised his brother on tactics. He was also responsible, according to Mr. Quirk’s book, for John Kennedy’s intervention in the Martin Luther King case. As Mr. Quirk related it, this is what happened:

“The Rev. Martin Luther King was arrested for staging a sit-in at a department store in Atlanta, and was forthwith sentenced to four months of hard labor in a Georgia penitentiary. This event occurred a scant week before the election.

Prompted Call to Mrs. King

“Bobby saw to it that J.F.K. called Mrs. King to offer comfort. Then Bobby called the judge who had sentenced Dr. King. Shortly afterward, the Negro leader was freed on bail, and a member of the King family declared, ‘I’ve got a suitcase of votes, and I’m going to take them to Mr. Kennedy and dump them in his lap.'”

After John Kennedy defeated Mr. Nixon — the popular vote margin was 119,000 out of 68 million cast — he appointed his brother Attorney General. Robert Kennedy was reluctant at first, saying, “Everything I do will rub off on the President.” He was also sensitive to the likely charge that the appointment was nepotic

John Kennedy, however, wanted his brother in the Cabinet as an absolutely loyal and dependable confidant. In public, when criticism of the appointment mounted, the President explained his choice almost flippantly. “I can’t see that it’s wrong to give him a little legal experience before he goes out to practice law,” he said.

Mr. Kennedy’s term as Attorney General touched many sensitive areas of the nation’s life– civil rights, immigration, crime, labor legislation, defense of the poor, pardons, economic monopoly, juvenile delinquency and the Federal judiciary.

In the opinion of his staff — and he recruited a brilliant group that included Byron R. White, now a Supreme Court justice, and Nicholas deB. Katzenbach, now Deputy Secretary of State — Mr. Kennedy was imaginative and inspiring. His relationship with J. Edgar Hoover, director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, was reportedly more formal than cordial after Mr. Kennedy made it known that he was Mr. Hoover’s superior in fact as well as in theory.

Conspicuously active in civil rights, Mr. Kennedy, among other achievements, exerted the Federal force that permitted James H. Meredith, a black student, to enroll in the University of Mississippi in 1962.

And owing to his relationship with the President, he had a hand in virtually every phase of the Administration. “Call Bobby, get together with him and come back with an idea on this,” was a frequent White House order

In foreign affairs, he was an especially close adviser. He investigated the Central Intelligence Agency after the Cuban Bay of Pigs fiasco in 1961. In the Cuban missile crisis the next year he opposed a pre-emptive air strike on Cuba and advocated the policy of restrained toughness that allowed the Soviet Union to retreat gracefully.

Mr. Kennedy was lunching at his home in McLean, Va., on November 22, 1963, when he was informed of his brother’s assassination in Dallas. Stunned, his shoulders drooping, his face solemn, he was at the airport when the Presidential plane landed in Washington with the President’s body, his widow, Jacqueline, and the new President, Lyndon B. Johnson. During the public rites that preceded the funeral, he never left his sister-in-law’s side. In the long, slow procession from the White House to St. Matthew’s Cathedral, he and his brother Edward, a Senator from Massachusetts, walked on either side of her. And at Arlington National Cemetery, both brothers helped her light an eternal flame over the grace.

Plunged Into Deep Grief

The assassination plunged Mr. Kennedy into a deep grief that amounted virtually to melancholy. His face was a mask; sadness enveloped his eyes; he seemed to have shrunk physically, and he often walked alone, his hands dug into his jacket pockets. And for the remainder of his life he lived with thoughts of his dead brother never far from the surface of his mind. When Dr. King was assassinated earlier this year, Mr. Kennedy was speaking at a political rally. Almost by reflex action he offered the family his condolences and remarked that he could understand their feeling of sudden loss because he himself had undergone a similar shock over his brother.

When his lassitude lifted, he set out to replan his political life. For a time in 1964 there was speculation that he might be President Johnson’s running mate that fall. Whatever hopes he had, however, were dispelled when Mr. Johnson ruled out all Cabinet members as Vice- Presidential material. Displeased, Mr. Kennedy resigned to run for the Senate from New York; and, establishing residence, he put into operation the political structure he had erected for his brother in 1960 and won the nomination without difficulty.

His opponent was Senator Kenneth B. Keating, the incumbent Republican, who sought to picture Mr. Kennedy as a grasping carpetbagger. “Isn’t the basic question ‘Who can best represent the State of New York?'” Mr. Kennedy retorted. And to the charge of being sinister, he replied:

“I like to be involved in politics. I like to be involved in government. I’ve been in politics all my life. I would like to remain in government. I don’t think that’s so sinister.”

He defeated Mr. Keating by 800,000 votes in a campaign that demonstrated the visceral appeal he had for voters. In the Senate (and a national figure in his own right) he forged a position slightly to the left of Mr. Johnson on the problems of the poor and the cities. He also sought to develop moderately “dovish” views on the war in Vietnam, but his opposition to Mr. Johnson on this issue always remained cautious.

It was so restrained, indeed, that he held back from contesting for the Presidential nomination of 1968 until after the New Hampshire primary on March 12 showed the extent of voter disaffection with the war. Thereafter, however, he fought keenly for the nomination, winning major primaries in Indiana, Nebraska and California.

Campaigning with him was his wife, the former Miss Ethel Skakel of Greenwich, Connecticut, to whom he was married in 1950. Mrs. Kennedy is expecting their 11th child in January.

Their other children are Kathleen Harrington, 16; Joseph Patrick, 15; Robert Francis, 15; David Anthony, 12; Mary Courtney, 11; Michael Lemoyne, 10; Mary Kerry, 6; Christopher George, 4; Matthew Maxwell, 3, and Douglas Harriman 14 months.

Robert F. Kennedy, brother of President John F. Kennedy, former attorney general, senator and presidential candidate, was shot on June 5, 1968, and died the next morning. The funeral Mass for Senator Kennedy took place at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, New York City, on Saturday June 8, 1968. The remains were then transported upon a slow-moving train to Washington, D.C., via Newark and Camden, N.J.; Philadelphia, Pa.; and Baltimore, Md. The railway system stopped all northbound traffic between Washington, D.C., and New York, and many people gathered along the route to pay tribute to Senator Kennedy.

The long transport delayed the arrival at Union Station until 9:10 p.m., and cemetery officials quickly changed the funeral plans to accommodate an evening interment. Floodlights were placed around the open grave and service members provided 1,500 candles which were distributed to the mourners.

The casket was borne from the train by 13 pallbearers, including former astronaut John Glenn, former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, family friend General Maxwell Taylor, Robert’s eldest son Joe, and his brother Senator Edward Kennedy.

The procession stopped once during the drive to Arlington National Cemetery at the Lincoln Memorial where the Marine Corps Band played “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” The funeral motorcade arrived at the cemetery at 10:30 p.m.

The brief grave-side service was conducted by Terence Cardinal Cooke, Archbishop of New York. Afterward the folded flag was presented to Ethel and Joe Kennedy on behalf of the United States by John Glenn.

In 1971 a more-elaborate gravesite was completed, at the request of the Kennedy family, by architect I.M. Pei (who also designed the East Wing of the National Gallery of Art). The new gravesite retains the simple, white Christian cross of the earlier site, and adds a granite plaza (like JFK’s gravesite which adjoins it) and two inscriptions from Senator Kennedy’s most notable addresses.

Senator Robert Kennedy’s funeral is the only one ever to take place at night at Arlington National Cemetery.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard