From contemporary press reports:

Retired Justice Harry A. Blackmun, the author of Roe v. Wade, the decision that made abortion legal, radically transformed American society and changed politics forever, died Thursday, March 4, 1999, at age 90 of complications following hip replacement surgery.

An enigmatic figure who could be both reserved and puckish, and who loaded his writing with emotion, Blackmun sat on the high court from 1970 until 1994 and penned hundreds of opinions. During that unusually long tenure he influenced all walks of life, but particularly enhanced women’s rights, enlarged constitutional protection for commercial speech and championed a high wall of separation between church and state.

Raised in Minnesota and educated at Harvard, Blackmun was appointed to an appeals court and the Supreme Court by Republican presidents. But when the small man with a full head of gray hair retired, he was the most liberal member of the bench. His ideological odyssey intrigued political Washington, but it was also a measure of the court’s transformation from the expansive post-Earl Warren era of the 1970s to the conservatism of the 1990s.

But more than anything, Blackmun was identified with the 1973 decision that found an implicit right of privacy in the Constitution broad enough to encompass a woman’s choice to end a pregnancy.

The 7-to-2 ruling ignited the culture wars that have come to dominate American politics. It stands as the single most important decision in the mobilization of the religious right, the linchpin of the women’s rights movement and the sexual revolution and a crucial development for the Republican party, which in the 1970s began drawing on Catholic, working-class Democratic voters.

Blackmun, who had been on the bench just three years when he crafted Roe, conceded it was difficult to write, not least because of the seemingly absolute convictions that the abortion controversy continued to inspire. But he would observe upon his retirement five years ago, “It’s a step that had to be taken … toward the full emancipation of women.”

That ruling inspired plenty of animus over the years, too, and Blackmun often recounted the hate mail he received. He was called a “low-down scum,” and a “murderer.”

For all the passion he penned and inspired in some opinions, the slight, unassuming Blackmun was somewhat detached. He was seen as a loner, rather than a leader. Fellow Minnesotan Garrison Keillor called him “the shy person’s justice.” On big days of oral arguments, as people lined up outside the white marble court building, Blackmun was occasionally spotted standing alone at the top of the steps, lost in thought.

He would sometimes joshingly call himself “Ol’ No. 3” because he was nominated by Richard Nixon after the president’s failed attempts to name Clement F. Haynsworth Jr. of South Carolina and G. Harrold Carswell of Florida. Blackmun, then an appeals court judge on the 8th Circuit and an old friend of then-Chief Justice Warren E. Burger, was confirmed without opposition.

The thought, “What am I doing here?” always crossed his mind, he said, as he was filled with humility at the task.

He changed a good deal during his 24 years on the court. He and the generally conservative Burger were allied at first and dubbed the “Minnesota Twins.” But Blackmun slowly and surely broke ranks and by the time he retired in 1994, he was the court’s most liberal member.

Blackmun himself bristled at all the commentary about his ideological shift and contended it was not he who changed. He said he adhered to the proposition that he was the same: “The court changed.”

Blackmun found his voice as he wrote about the plight of victims and underrepresented in society. When the court ruled that the mother of a 4-year-old boy, Joshua DeShaney, whose father savagely beat him, could not sue a county welfare department for failing to protect the boy, Blackmun penned a dissent famous for its unshielded emotion.

“Poor Joshua!” he said in the 1989 case. “Victim of repeated attacks by an irresponsible, bullying, cowardly, and intemperate father, and abandoned by [the social services workers] who placed him in a dangerous predicament and who knew or learned what was going on, and yet did essentially nothing… It is a sad commentary upon American life.”

Reacting to the growing conservatism of a court and rulings that made it harder for workers to sue for bias, Blackmun wrote, “One wonders whether the majority still believes that race discrimination – or, more accurately, race discrimination against non-whites – is a problem in our society, or even remembers that it ever was.”

Two months before he announced his retirement in April 1994, Blackmun, who consistently voted to uphold death sentences, said he had come to believe that the capital punishment system was fraught with discrimination and mistakes. “From this day forward,” he said, “I no longer shall tinker with the machinery of death.”

He asked questions about “the real people” who would be affected by a ruling, the “little people,” he said, who had no angels. But he could be gruff and a stern taskmaster to his law clerks and himself, spending long hours hunched over stacks of books in the court library.

And his sentimental approach was criticized by legal scholars who said he was too emotional and that he failed to follow precedent or offer guiding principles for future cases.

After his retirement in 1994, he continued to come daily to the court and keep up his tradition of heading down to breakfast in the cafeteria with his clerks. On Feb. 22 he fell at his home and the next day underwent hip replacement surgery. He never fully recovered. But true to his work ethic, he considered having some of his mail delivered to the hospital so he could keep up with correspondence.

A Supreme Court statement said Blackmun died at 1 a.m. in Arlington Hospital in Arlington, Virginia. He was survived by his wife, Dorothy, and their three daughters.

Retired Justice’s Body to Lie in Repose

The body of retired Justice Harry A. Blackmun will lie in repose at the Supreme Court building Monday, and a memorial service is scheduled for Tuesday.

Blackmun, who served on the nation’s highest court for 24 years before his 1994 retirement, died Thursday. He was 90.

Court spokeswoman Kathy Arberg said Blackmun’s coffin will be in the court building’s Great Hall from 1 to 8 p.m. Monday, and public admittance will begin at 2 p.m. Blackmun’s memorial service will be at 1:30 p.m. at Metropolitan Memorial United Methodist Church. The service will be open to the public. Burial services will be private.

BLACKMUN, The Honorable HARRY ANDREW

Associate Justice, US Supreme Court (Ret.)

On Thursday, March 4, 1999, JUSTICE HARRY ANDREW BLACKMUN. Beloved husband of Dorothy E. Clark Blackmun; father of Nancy Clark Blackmun, Sally Ann Blackmun and Susan Manning Blackmun; grandfather of Nicholas J.B. Coniaris, Kristen B. Coniaris, Lauren B. Elsberry, Elizabeth B. Elsberry and Kaia B. Brown; uncle of Peter Michael Gilchrist and Cathy Gilchrist Kaudy.

Justice Blackmun will lie in repose in The Great Hall of the United States Supreme Court on Monday, March 8 from 2 to 8 p.m. Memorial services will be held at Metropolitan Memorial United Methodist Church, 3401 Nebraska Ave., NW, Washington, DC. Interment private.

In lieu of flowers, memorial contributions may be made to the Harry A. Blackmun Scholarship Foundation, 118 W. Mulberry St., Baltimore, MD 21201; or the Mayo Foundation, Office of Development, Rochester, MN 55905. Arrangements by JOSEPH GAWLER’S SONS. Funeral services to be covered by C-Span.

Blackmun and the Bug

Folks who saw Supreme Court Justice Harry A. Blackmun’s funeral procession last week en route to Arlington Cemetery may have been surprised by the new bright blue Volkswagen Beetle midst the standard dark limos and other cars.

Seems Blackmun had driven a blue bug for many years–the original version, not the fancy new one selling these days — and his ashes were in a container in the front seat of the one taking him to his final resting place.

Dorothy Blackmun, 95, widow of jurist, dies

18 July 2006

Dorothy Clark Blackmun, whose late husband wrote the Supreme Court decision that legalized abortion nationwide, died at a Winter Park assisted-living facility Thursday. She was 95.

Her husband, Harry Blackmun, served on the high court from 1970 to ’94 and was the author of the 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling.

The decision prompted death threats, and in 1985 a gunman fired a bullet into the Blackmuns’ suburban Arlington, Virginia, apartment. They were home at the time but not injured.

Born in a small town outside Duluth, Minnesota, Dorothy, who went by the nickname “Dottie,” overcame family difficulties to earn a full scholarship to a St. Paul, Minnesote, college. She dropped out because of the Great Depression and took a secretarial job.

The Blackmuns met during a doubles tennis match and dated for four years. They married in 1941 and had three daughters: Nancy, Sally and Susan.

She was a partner in a dress shop in Rochester, Minnesota, while her husband served on the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

“She had been apprehensive about being a judge’s wife when Dad went on to the court of appeals,” Nancy Blackmun said, adding that her mother had a warm and funny nature. “She found a way to be humorous about it.”

President Nixon elevated Harry Blackmun to the Supreme Court in 1970. When he retired at age 85, he was the court’s most liberal member.

Dorothy Blackmun was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease when she was in her early 70s. Her husband died in 1999 from complications after hip-replacement surgery. She moved to Florida shortly after his death.

She will be cremated, and her ashes will be buried with her husband’s ashes in Arlington National Cemetery.

Her daughters plan a memorial service in Washington this fall.

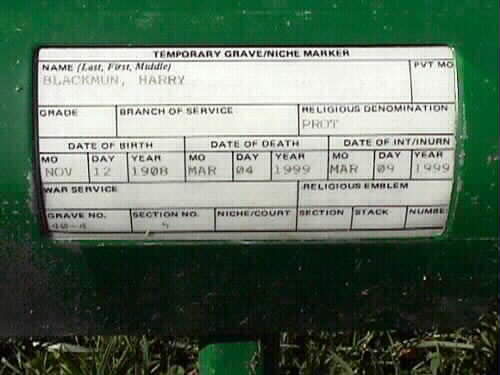

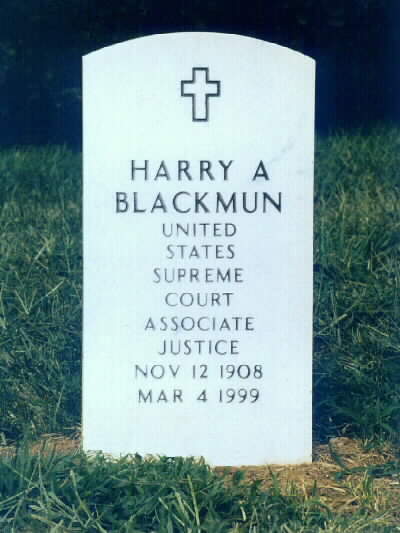

BLACKMUN, HARRY A

PVT US ARMY

- DATE OF BIRTH: 11/12/1908

- DATE OF DEATH: 03/04/1999

- BURIED AT: SECTION 5 SITE 40-4

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

BLACKMUN, DOROTHY

- DATE OF BIRTH: 12/12/1910

- DATE OF DEATH: 07/13/2006

- BURIED AT: SECTION 5 SITE 40-4

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard