A Message From Brad Colip, 26 August 2001

I would like to suggest a Story Of The Week. The individual is Michael McPherson Deuel, Captain, USMCR. I found out about him while reading The Book Of Honor (Chapter 7). Michael is buried in Grave 156, Section 35. What makes him special is not the fact that he was a Captain in the USMCR, but that he was a CIA operative killed by a helicopter crash in Laos in 1965. The crash was ruled due to mechanical failure not hostile fire. While he has a name at Arlington just a few miles away at Langley he is a nameless star on a wall and a blank line in The Book Of Honor. Michael was a second generation CIA warrior and he left behind a widow and a daughter he never met. He was posthumously awarded the Defense Intelligence Medal in 1966. I’m sure there are many other CIA operatives buried in Arlington who took their cover with them to the grave, but I think these individuals are long overdue for some recognition. I’m sure that you can put together something far more eloquent than I can to honor Michael McPherson Deuel.

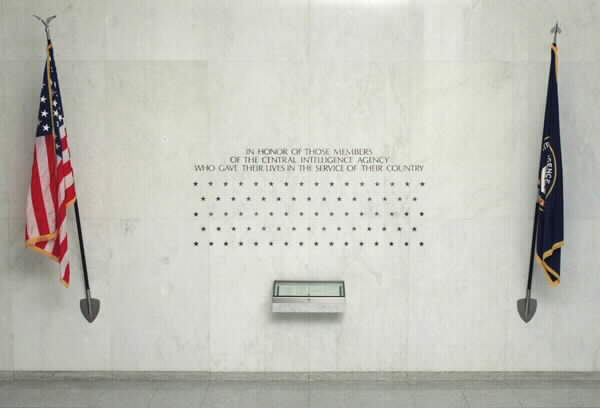

Michael’s name was finally revealed in the Book Of Honor sometime after 1997. Ted Gup is the author of The Book Of Honor and “The Two Mikes” is Chapter 7 of Ted’s book. In the picture of the Memorial Wall I sent you the actual Book Of Honor is the object in the case below the stars. Ted Gup decided to author his book of the same name after going to the CIA researching another book. He noticed how many lines in the original Book Of Honor are blank (see the other picture I sent you) and decided to find out who they were. He was able to

identify all of them. He titled his book after the actual Book Of Honor as a way to tie it back to the CIA, I guess.

Michael McPherson Deuel. Cornell Class of 1959, was born in Berlin, Germany on May 13, 1937. His father Wallace Deuel worked as a foreign correspondent for the Chicago Daily News before the start of World War II. His family later moved to Washington, DC, where he played high school football and was president of his class. Deuel was one of 25 National Scholarship winners to enroll at Cornell in 1955. While at Cornell he was a brother in the Sigma Phi fraternity and played varsity lacrosse. In 1959, he graduated from the College of Arts and Sciences.

Deuel was then commissioned as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Marine Corps, and eventually shipped out to Southeast Asia. He returned home safely in 1962 and was honorably discharged from the Marines. However, his love of Southeast Asia and its people during his stint in the Marines compelled Deuel to return there.

In 1964, Deuel became a refugee relief advisor for the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and was stationed in Pakse, Laos. The Pakse area of Laos had several thousand Meo refugees who had fled their mountain homes from the invading communist Pathet Lao and Viet Minh forces. It was there that Deuel was to participate in what history has since defined as “the secret war” against the communists.

His true role in Southeast Asia, declassified decades later would disclose that he was a CIA covert operative. Eight months after he was stationed in Laos, Deuel married the former Judith Dougherty, a secretary in the U.S. Embassy in Bangkok, Thailand.

In 1965, Marquis Childs of the Washington Post (not knowing of Deuel’s affiliation with the CIA) wrote the following cover story about Deuel: “The choice he had made of what he wanted to do with his life says a lot … He worked in a primitive village under difficult and often frustrating circumstances. He wanted to be where the action was, where things were happening. One of his family’s vivid memories is of his saying with passion: “I’ll tell you one thing and that is I don’t intend to be bored in my life.”

On October 12,1965, Deuel was planning to take three other Americans on a tour of the area. However, the helicopter they were riding in developed mechanical problems and it crashed shortly after taking off from Saravane, Laos. Michael Deuel was only 28 years old when he died. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. He is not listed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial because he was not a military loss. For a feature story on Michael Deuel’s life and involvement in the CIA in “The Two Mikes” by Ted Gup.

THE TWO MIKES

BY TED GUP

To the outside world, Mike Deuel was a young U.S. aid officer who died helping the people of Laos. Few knew his real job: CIA operative.In a new book, Investigative Journalist Ted Gup exlores the hidden lives of Deuel and fellow agents who became casualties of the Cold War.

At ten o’clock on a sunlit Sunday morning–October 10, 1965–two young men in khakis, both named Mike, hoisted themselves aboard an Air America chopper and lifted off from a tiny air base in Pakse, Laos. One was Mike Deuel ’59. The other, Mike Maloney.

Both were said to be with the Agency for International Development, helping to resettle displaced refugees. Their true purpose, stamped “Top Secret,” would, for decades, keep the Central Intelligence Agency from speaking of their mission or even uttering their names.

These two young bulls–Deuel was twenty-eight, Maloney twenty-five–were as close to royalty as the agency possessed. What set them apart from other young covert operatives was that they were among the first sons of CIA career officers to take to the field. That Sunday morning flight was in itself of no great political or military consequence. But to the few at Langley cleared to know the names behind the code names and familiar with the lineage of these two men, it was something of an epochal event.

It marked the beginning of the end for that first generation of CIA officer who had come out of World War II and the Office of Strategic Services, and it ushered in a whole new era of clandestine warrior. By 1965, two full decades after World War II, the CIA’s wartime veterans were entering their fifties and sixties. Balding and slower of step, they were sagelike presences in the halls of Langley, already cast in supervisory and support roles and, but for a defiant few, reluctantly accepting desk jobs. They understood it was time to leave the action to the “kids.”

Over time, the novelty of a second generation of CIA officer would fade. More and more sons and daughters, nieces and nephews, were drawn into the fold of clandestine service. In time, they would come to form an unseen class with a culture all its own. Raised within a raucously open society and yet a breed apart, they were reared to believe in the indispensability of espionage and the virtues of secrecy. They came to accept what the wider population could not–that even the ultimate sacrifice must sometimes go unrecognized. As public suspicions of the agency deepened in the aftermath of the Bay of Pigs and the quagmire of Vietnam, the CIA increasingly gathered unto itself its own sons and daughters. They, above all others, could be trusted.

Mike Maloney’s father, Arthur, was born in Connecticut in 1914. “Mal” attended West Point, where he was the very embodiment of gung ho, even as a member of the backup lacrosse squad. He graduated in 1938 and one year later married Mary Evangeline Arens, a chestnut-haired coed with a will all her own. A year later they had a child, a son named Michael Arthur Maloney. In August 1946 Mal retired from the military as a full colonel. With the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950 he volunteered for duty but was rejected because of a bum leg. And so it was by default that he came to the CIA in March 1951. It was as close as he could get to the front lines.

If Mike Maloney’s father was a man of action, Mike Deuel’s was a man of words. His name was Wallace, but he was known as Wally. He was a bookish figure with an owlish face, horn-rimmed glasses, and a slim frame, the sort of fellow pictured on the beach getting sand kicked in his face. By trade he was a newspaperman, a world-class foreign correspondent for the Chicago Daily News. He had the good fortune in 1934 to be posted to Berlin even as Hitler consolidated power. Deuel would remain there for seven years. During that time he made a study of the Reich and published a book, People Under Hitler, a scathing account of German despotism. The Reich dubbed him “the worst anti-Nazi in the whole country.” It was during his tenure as Berlin correspondent that Wally and his wife, Mary, had two sons. Peter was born in 1935 and Mike on May 13, 1937, in Berlin.

With the outbreak of World War II, Wally Deuel joined the OSS, the forerunner to the CIA. He was named special assistant to Wild Bill Donovan, the charismatic leader of the OSS. Not cut out for the derring-do of covert military operations, Deuel took on a variety of tasks, even working with Walt Disney on a cartoon propaganda project. After the war, Wally Deuel took a job as diplomatic correspondent for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, but in 1953 he was laid off and called upon his well-placed friends to help him find a job. In January 1954 Deuel took the oath of office, passed his final security interview, and signed a loyalty affidavit at CIA headquarters. He was a GS-15 with a starting salary of $10,800 a year, but he was jubilant, and once again intoxicated with the mystique of espionage, even though his career would rely more on his skills with a typewriter than a garrote or codebook.

Where Wally Deuel had always been most comfortable standing on the sidelines, his son Mike was determined to be a player. Wherever the action was most intense, that was where Mike Deuel wanted to be. He was what his father always hungered to be–not the scribe but the doer, living on the edge. Mike was all of that, a romantic and roguish figure in whom his father could realize a lifetime of pipe dreams.

Physically Mike Deuel was not particularly formidable, but he had little regard for his own well-being and even as a child took pride in throwing himself in the way of the biggest kid on the playing field. There was little that Mike Deuel did not excel at. Where natural talent failed, pure gumption kicked in. At Washington’s Western High School he played fullback and made the D.C. All-Star team while serving as president of the student council. Graduating in 1955, he went to Cornell as one of the school’s twenty-five National Scholars.

At Cornell Deuel played lacrosse and eagerly awaited the day his team faced Syracuse and the chance to butt heads with that school’s most fiercesome athlete. Butt heads he did, though in each collision he got the worse of the exchange. The player he was so determined to stop was named Jim Brown, who would go on to become one of the greatest running backs in NFL history. Deuel’s classmates watched in disbelief as the modest-sized Deuel attempted in vain to stand his ground against the broad-shouldered juggernaut from Syracuse. Such pluck became the stuff of myth.

With prematurely salt-and-pepper hair cropped to a perfect brush cut, a devil-may-care smile, and squared jaw, he was a dashing figure–never more so than when he once returned to Cornell from the marines in full dress uniform, starched blue collar, white gloves, scabbard, and swagger stick. He was the very image of the sturdy warrior but not quite able to fully conceal the little boy’s thrill to be in uniform.

Deuel chose the marines because he hoped they would meet his own standards of toughness. It was not that he spoiled for a fight, but he was constantly looking for ways to test his mettle. As an officer, however, he seemed oddly distanced from the tasks at hand. To a classmate he wrote on July 16, 1960: “We still take orders from mean men afflicted with chronic flatulence, and we still run until puddles of earnest sweat accumulate around us.” He seemed mildly amused by the regimentation. “I’m drunk with power but clear of eye,” he wrote his family in 1961. “My hair is short and so is my patience.”

But for Mike Deuel, not even the marines supplied enough action. In a letter home he wrote: “Life here creeps on in an undetectable pace, so much so that I am thrown back on my strong inner resources–tobacco, (awful) whiskey, and pornography.” Hungry for action, Deuel left the marines and in 1961 joined the CIA, where he sought out the clandestine service and the most rigorous training the CIA offered. While nearly all clandestine officers passed through Camp Perry with its indoctrination courses and basics in tradecraft, Deuel applied to undertake the specialized program in jungle warfare.

From the jungles of the Canal Zone, Deuel was sent to Langley to serve on the Laos desk, providing tactical and logistic support for men in the field. He understood, as did everyone in the clandestine service, that Laos was center-stage in the struggle with communism. As far back as January 19, 1961–the day before Kennedy’s inauguration–the incoming president and the outgoing Eisenhower had spent more time discussing Laos than any other subject. Following a 1954 international agreement, Laos was to remain neutral, free of outside intervention and superpower meddling. But the communists ignored such restraints, and the U.S., in what came to be known as “the secret war,” fought to repel them and disrupt the tide of men and matériel that flowed through the country along the Ho Chi Minh Trail and into the hands of the North Vietnamese.

“Laos,” Kennedy once declared, “is far away from America, but the world is small. . . . The security of all Southeast Asia will be endangered if Laos loses its neutral independence. Its own safety runs with the safety of us all–in real neutrality observed by all.” Instead of neutrality, Laos would be decimated by undeclared war. Not since the Bay of Pigs had the CIA staked so much on a single foreign gambit.

Deuel seized the first opportunity to go to Laos. To his mother and father he wrote: “After about a week starts a job big and responsible enough to inspire equal parts of pleasure and panic. In times past, this combination has been enough to overcome my habitual mental lassitude; there may be cause for optimism. . . . But, now to my rude bower. Tomorrow, I must fight off wild Asian tigers and semi-wild Eurasian girls. Once more into the Breech?”

It was a raw existence that Deuel lived, working fifteen to twenty hours a day, seven days a week, then collapsing in exhaustion. At times he saw his role in almost Wagnerian terms, but was always quick to puncture any sense of self-importance. In a letter home, twenty-six-year-old Deuel wrote: “In fact there are no dramatic reports a’tall a’tall. All is prosaic, too much so. . . . I dream of glory and future excitements. Of course when I get them, I’ll probably ask for the next boat home.”

At about the same time that Deuel arrived in Laos, a twenty-two-year-old CIA secretary named Judy Doherty was working at agency headquarters in Langley, Virginia. Asked where she might like to be posted, she listed Paris and Rome and Lima, names out of a small-town fantasy. Some time later an agency officer informed her she had been assigned to Bangkok, Thailand. She had never heard of it. In November 1962 she found herself working at the embassy there under State Department cover. There she met the dashing young Mike Deuel, though she had earlier caught the eye of both Deuel and his friend and colleague Dick Holm when all three were still at Langley.

But it was Deuel who began courting Judy. In late August 1964 he “smuggled” her into Pakse, aboard one of the Air America planes at his disposal. His purpose was to give her a “cold-eyed look” at his lifestyle and to see how she might cope with it. His home was a farmhouse with high ceilings and many windows, a mix of French and Lao. His bed was a cotlike affair, a bamboo platform with two blankets. Judy passed the test brilliantly. “She’s so sensible that she’s downright unromantic sometimes,” he wrote. “This is good. Starry eyes would not be an asset.”

At 1 p.m. on October 30, 1964, Judy Doherty and Mike Deuel were married in the Holy Redeemer Church in Bangkok. Both of them were so nervous that they would later laugh about the muscles twitching in their faces. After a brief honeymoon at the beach, the couple moved to Pakse. There Judy helped manage the agency’s base operations and plotted on a map the reported sightings of enemy convoys. “All in all,” wrote Mike Deuel to his parents on November 29, 1964, “things are a little too good to last; we’ll have to have some bad luck ere long. Meanwhile, the sun is shining and I’m making hay as fast as I can move, trying not to look too smug.”

By that summer the covert operations within Laos were expanding daily and more agency case officers were needed. Mike Deuel was about to get some help and, if things worked out, even a replacement. In September 1965 help arrived in the person of Mike Maloney. Maloney, like Deuel, was a paramilitary officer, a quiet young man with a gleaming smile, deep-set dimples, and–from his father–full brows and a barrel chest. And like his father, Mike Maloney’s first choice had been the military. But the military refused to take him because of asthma. And so, by default, he joined the CIA.

To break in the younger Maloney, Deuel invited him to Pakse. That Saturday night, October 9, 1965, the two young officers could get acquainted. Maloney’s wife, Adrienne, was getting settled in Bangkok. Later they planned to move to Pakse. It seemed a perfect match–the two Mikes, both young, gung-ho case officers, both the sons of CIA officers, both their wives pregnant.

Mike Maloney had married his college sweetheart, Adrienne La Marsh, on October 5, 1963. Already they had a one-year-old son, Michael, and the second child was due in four months. The Maloneys had just celebrated their second anniversary. The Deuels were two weeks from celebrating their first.

The next morning, a Sunday, the two Mikes were scheduled to board a chopper, survey the region, make some payroll stops at area villages, and introduce Maloney to the tribal leaders with whom he would be working. Judy Deuel watched as the two Mikes piled into Deuel’s Morris Mini and sped off on the drive across the river to the airstrip. They were scheduled to be back home about two that afternoon. That morning Judy went by herself to a French Mass held in a small country church, then returned home. At two the men had not yet returned. She began to worry. She sat down at the piano, as she often did, to play a piece of classical music and drown out the voice of fear that often preceded Mike’s belated returns. She had one eye on the ivory keyboard, the other on her watch.

It was three. It was four. It was five. Now it was dusk. She knew they would not choose to fly in such poor light. Not long after, an agency operations officer arrived at the house. He looked grim. He said that some villagers had reported seeing a chopper go down near a place called Saravane. The officer took Judy to the airport and there they waited for word.

At the first light of morning, the agency dispatched a search team. That afternoon they spotted something through the trees and radioed for help. In Vientiane a medical officer at the embassy, Dr. Burton Ammundsen, was dragooned into a rescue mission. By the time the chopper carrying Ammundsen reached the site where the wreckage had been spotted, it was sundown. Armed with only a flashlight, he spent the night on a small island. The next morning an agency rescue team linked up with him and cut its way through the forest. The wreckage was less than a hundred yards from the river where Ammundsen had spent the night. But it was evident that there was nothing for him to do. The chopper had been badly mangled. There were four bodies–the two Mikes and those of an Air America pilot and mechanic.

The deaths of Mike Deuel and Mike Maloney received scant attention in the newspapers. The brief obituaries spoke of two young AID officers killed in a helicopter crash. But one of Wally Deuel’s journalist friends, conservative columnist Marquis Childs, wrote a panegyric to Mike Deuel. The headline read: “Commitment of Young American to Life Ends in Death in Laos.” Childs, unaware that Deuel had been CIA, spoke of Deuel’s selfless efforts to resettle refugees, extolling him as part of a generation of peace-loving Americans.

There was grim irony in the CIA’s choice of cover story, the idea that Deuel, Maloney, and other operatives in Laos were working for AID on refugee resettlement issues. The reality was that their mission was adding to the refugee problem and creating an ever-greater need for AID’s assistance. As the CIA succeeded in attracting more and more indigenous tribesmen to its anticommunist units, there were fewer and fewer men left home to harvest rice and other food crops. In time, so many men were enlisted into the CIA-backed units that there might well have been widespread famine had it not been for the intervention of genuine AID missions in the region.

Deuel was buried in Arlington National Cemetery in grave 156, section 35, just to the south of the Memorial Amphitheater and the Tombs of the Unknowns. As with so many covert CIA officers buried at Arlington, there was no hint that he had been with the agency. He left a father, a mother, a pregnant widow, and little else–a bank account with $1,869.14 and his beloved 1952 MG valued at $200.

It was later determined that mechanical failure, not enemy fire, had downed the aged helicopter. Indeed, many of the aircraft in use in Laos were in desperate need of replacement. Not long after the crash, CIA station chief Philip Blaufarb made a formal request that his men receive more modern aircraft. His request was denied.

Wally Deuel would never recover from the loss of his son, though he tried to put up a solid front and find meaning in the tragedy. Through it all, he and his wife continued their weekly visits to Dick Holm at Walter Reed Army Medical Center, where Holm was recovering from severe burns and other injuries sustained in a plane crash in the Congo the previous February. It was as if Wally Duel could do no less out of memory for his son–or perhaps it was that in some way Dick Holm, who had survived a plane crash and was one of his son’s best friends, had become a son to him. And on September 1, 1968, three years after Mike Deuel died, his widow walked down the aisle again. The groom was Dick Holm.

Wallace Deuel retired from the CIA in August 1968. His health deteriorated until he was, in his words, “chairbound.” But Deuel’s “melancholy,” as he called it, was brought on not only by his own physical decline but by a lingering sense of loss and by the spectacle of his beloved CIA in the throes of what appeared to be self-destruction. The agency was coming under increasing public scrutiny and criticism, as was the entire U.S. government. Watergate had erupted. Ugly accounts of CIA excess were coming to light, an omen of darker revelations to come. And then there was Vietnam.

Public suspicion of the CIA deepened. Support for covert activities was waning. Sordid accounts would surface of domestic surveillance under Operation Chaos, of efforts to destabilize the government of Chile’s Salvador Allende Gossens, and of the ruthless Phoenix Program in Vietnam, in which more than twenty thousand were killed.

Mike Deuel’s daughter, Suzanne, was born in the spring of 1966, two years before Judy Deuel and Dick Holm were wed. Suzanne was raised believing that Dick Holm was her biological father, but she sensed something was amiss. She was nine or ten when she stumbled across a box of old records and memorabilia in the basement. For hours she dug through the crate, fixated on photos of a man whose smile and eyes bore an uncanny resemblance to her own. She found his lighter, his ring, and newspaper accounts of a plane crash. She also found references to his burial at Arlington.

When she turned sixteen and got her driver’s license, she secretly drove to Arlington National Cemetery and found her father’s grave. But Suzanne never felt comfortable asking her mother or Dick Holm about the man she had come to know as Mike. He would remain a shadowy presence throughout her adolescence, a face she could see hints of in the mirror but would come to regard as a taboo subject.

A decade later, when she was living in Paris and engaged, she wrote one of her father’s Cornell classmates, asking if he might share with her some memory of Mike Deuel. That classmate contacted the entire Sigma Phi fraternity house, who, one by one, poured out years of memories. By the time Suzanne married, she had come to know her father as few daughters ever do.

Ted Gup, an investigative reporter who teaches at Case Western Reserve, has worked for Time and the Washington Post.

DEUEL, MICHAEL MCPHERSON

- CAPTAIN USMCR

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: Unknown

- DATE OF BIRTH: 05/13/1937

- DATE OF DEATH: 10/12/1965

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 10/25/1965

- BURIED AT: SECTION 35 SITE 156

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard