Pilot shot down during Vietnam War identified through DNA

Tuesday, January 11, 2000

BOCA RATON, Florida – A Navy pilot missing in action for 32 years will get a hero’s burial at Arlington National Cemetery this week, after DNA testing identified his remains.

Lieutenant Commander Michael Edward Dunn was serving a second tour of duty when his jet was shot down near Hanoi on Jan. 26, 1968. Officials listed the 26-year-old Navy pilot as missing in action.

Dunn will be buried Friday at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia. The funeral marks the end of three decades of uncertainty for family members, who will fly in from Florida, Barbados and Trinidad to lay Dunn to rest.

Dunn’s family, some of whom live in Boca Raton, had received several clues about his fate over the last five years. In August, DNA tests confirmed that remains found in Vietnam nearly two years earlier were Dunn’s.

“We’ve waited so long for this closure,” said Catherine Doherty, Dunn’s youngest sister, from her Chesapeake, Virginia, home.

In 1995, when the family had assumed they would never be able to recover Dunn’s remains, the Navy discovered his flight bag in a Hanoi Museum.

Navy officials later found what looked like the wreckage of the pilot’s A6 jet and what turned out to be his remains.

His siblings gave blood for DNA analysis, but had to wait two years for Vietnamese officials to release the remains.

“My whole life I’ve heard about him and what a wonderful person he was,” said Christine Kingery, 28, a Boca Raton resident who hadn’t been born when her uncle died. “Now I can pay my respects.”

Kingery, her mother Sharon Kingery, and other Florida relatives will meet family members at the funeral, including Dunn’s siblings Christopher Dunn, a Washington lawyer, and Doherty, who was 10 when officials reported her brother missing.

In the 1960s, thousands of civilians vowed to wear copper or silver bracelets listing the names of soldiers missing in action.

Mrs. Kingery has received about a half dozen bracelets engraved with her brother’s name in the mail, accompanied by letters requesting that they be included in his casket.

“That strangers would wear a bracelet honoring my brother for so many years is moving beyond words,” she said. “It’s truly a tribute to the caring, resilient human spirit.”

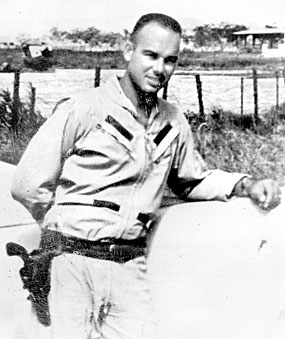

Michael E. Dunn

Portions Courtesy of People Magazine, 1 May 2000

MICHAEL EDWARD DUNN was born on July 6, 1941 and joined the Armed Forces while in Naperville, Illinois.

The funeral looks and sounds like any other at Arlington National Cemetery. There is the flag-draped casket, the military honor guard, the 21-gun salute, the clear, piercing notes of “Taps.” But when Christopher Dunn begins speaking to the 40 people gathered to mourn his brother, Navy Lieutenant COmmander Michael Dunn, it becomes clear that this one is different/

“My hero comes home to rest where he belongs, in a field of heroes,” says Dunn, a Washington, D.C. lawyer, in a quavering voice. “He was lost, but now he is found.”

It was 32 years ago – on January 26, 1968 – that the Navy A-6A attack jet carrying Dunn, 26, and his pilot, Captain Norman Eildmoe, 34, went down over North Vietnam. When the war ended, the two were among 2,583 American servicemen listed as missing in action in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. For years the Dunns and Eidsmoes, like other families, lived with the gnawing questions. “You don’t want to give up, ever,” says Betsy Eidsmoe, now 67, who had five children with Norman. “You always think, ‘Well, maybe they got out.'”

Though most authorities agree that there is next to no chance any American MIAs are still alive in Vietnam and its neighboring countries, more and more questions about what happened to each of them are being answered, thanks to a concerted international effort – dating from 1973 – to find and identify remains of U.S. servicemen, 554 of whom have been identified. The task of searching for the 2,029 Americans still unaccounted for in the region involves a network of several hundred military personnel, diplomats and scientists from four countries, whose work combined negotiation, forensics, archeology and old-fashioned sleuthing. Ultimately they hope to account for every missing American. “This is part of the national psyche – we don’t leave our buddies behind on the battlefield,” says Pentagon MIA chief Robert Jones. “We do everything we possibly can to bring them home.”

Overseen by the Joint Task Force-Full Accounting and the U.S. Army Central Identification Laboratory, both based in Hawaii, the program every year undertakes 11 missions, each of which lasts 35 days. Though every mission is different and may involve separate searches for as many as 50 MIAs at at time, the painstaking approach is always the same.

Winding path takes MIA bracelet to family

Courtesy of the Chicago Sun-Times

The metal bracelet had been examined, displayed, thought about and talked about for decades.

In recent years, it had been resting safely in a jewelry box in Rockdale, Texas.

It was one of nearly five million bracelets issued during the 1970s by groups concerned about the thousands of soldiers who were presumed prisoners or missing in action in the Vietnam War. Its nameplate read: “LCDR Michael Dunn, 1-26-68.”

James Blain, the Texas man whose wife had worn the bracelet years ago, started thinking maybe the Internet could help find out more about Lt. Cmdr. Dunn, who once lived in Naperville, and perhaps find his family.

Blain e-mailed a Chicago Sun-Times reporter, who tracked down Christopher Dunn — the soldier’s younger brother, now working as an attorney in Washington, D.C. — and put them in touch.

“It’s the end of a 30-year search,” said Blain, who served stateside during the war. Christopher Dunn said he was appreciative of Blain’s “devoted faithfulness” to his big brother and personal hero.

Anti-war emotions ran high

Even now, Christopher Dunn told Blain, he often thinks of Michael Dunn and the potential that was taken away.

Michael Edward Dunn’s family moved to Naperville when he was a young man in the mid-1960s. A graduate of Texas A&M University with a degree in history, he enthusiastically joined the Navy and completed his first, one-year tour of Vietnam.

It was on his second tour, on Jan. 26, 1968, that Michael Dunn, 26, and Capt. Norman E. Eidsmoe of South Dakota disappeared while on a low-level nighttime bombing mission over North Vietnam, leaving American military officials unsure of their fate.

Michael Dunn’s sister, Sharon Kingery Motin, was 23 and pregnant when her closest sibling went missing.

“His last letter to me said he was so happy for me, and if I had a boy, that he hoped I would name him Mike,” said Motin, now of Boca Raton, Fla.

Military brass cautioned the Dunn family to keep quiet to avoid jeopardizing other POW/MIAs and military operations.

“It was absolutely horrendous,” she said. “We were not allowed to speak of the war. . . . That made it almost impossible to deal with. The next day I went to work and told nobody.”

Anti-war emotions ran high at the time, and Motin feared people’s reactions to her brother’s fate.

Seeing someone wearing a bracelet was one of her few sources of comfort, Motin said. She likens the bracelets, sold beginning in 1970 by Voices In Vital America in cooperation with the National League of Families of American Prisoners and Missing in Southeast Asia, to the popular yellow “LIVESTRONG” bracelets sold today to support cancer research.

Hates war, supports troops

“I got hundreds of letters from people saying, ‘Hi, my name is so and so, I live in so and so, and the bracelet I happened to get was your brother’s,’ ” Motin said. “I wrote, I would say, hundreds [of letters], because everyone, I felt, deserved a response.”

Motin says she’s heartened by the way today’s soldiers are treated more sympathetically by the public, even by people like her who are angry about the war in Iraq. “I hate this war, but I support the troops 100 percent,” she said.

A bracelet with Michael Dunn’s name also was wrapped around the wrist of Jack Shiffler of Naperville, a Vietnam vet who knew Motin and bought the bracelet to honor her brother.

Shiffler, a past commander of the Judd Kendall Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 3873 in Naperville and a charter member of DuPage County VietNow, said the Dunn bracelet helped him through some tough times.

“For a while it was my only hold on the Vietnam War, because he was the only guy missing from Naperville,” Shiffler said.

Remains found

Michael Dunn’s and Eidsmoe’s remains were discovered in 1997 and 1998 searches of the crash site in a rice paddy near Vinh in Nghe An Province.

The remains were returned to the United States, and Michael Dunn was finally buried on Jan. 14, 2000, in Arlington National Cemetery. Christopher Dunn, Motin and their sister, Catherine Doherty, attended, along with Shiffler and others.

Several bracelets, including Shiffler’s, that had been turned in to the family were buried with Michael Dunn.

Now the family will have one more. Blain is planning to mail his bracelet to Christopher Dunn.

Blain says he’ll always feel a connection to Lt. Cmdr. Michael Dunn, the man whose name symbolized, for so many years, the ones who didn’t make it home.

“Being a veteran, and knowing what they did not get when they got home, those who came home . . . it’s special in my heart to be able to give something back to the family.”

Dunn, Michael E

Born 6 July 1941

Died 26 January 1968

YS Navy, Lieutenant Commander

Residence: Chevy Chase, Maryland

Section 66, Grave 941

Buried 14 January 2000

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard