Sandra Foster

Attack Location: Pentagon

Age: 41

Home: Clinton, Maryland

Sandra Foster, 41, may be already one of the most well-known victims of the attack on the Pentagon, in part because her husband, Kenneth Foster, 48, kept a 44-hour vigil after American Airlines flight 77 crashed into the building.

Kenneth Foster began working anonymously next to rescuers minutes after the plane hit. His vigil over the burning remains of what was once his wife’s third-floor office were chronicled in Thursday’s Washington Post.

Foster finally was asked to leave and decamped to a nearby hotel, where many families of victims are staying. He said yesterday that he had nothing more to say.

Last week, Foster said: “Everyone should have a wife like I have. She’s an angel.”

His wife — still listed as unaccounted for — had worked at the Pentagon for almost 25 years. She started while she was in high school, when she was hired as a civilian by the Defense Intelligence Agency.

Her neighbors recalled Sandra Foster as quiet and sweet, and said that she and her husband, a retired Army soldier who works for the Army as a civilian, frequently tended their yard together in the Kirby Woods neighborhood in Clinton. She was an avid Redskins fan and he an avid Cowboys fan, and the two

frequently teased each other about their football rivalry.

“She was just a sweetheart,” said neighbor Sandra Stewart, 45. “She loved kids.”

Sandra Foster was close to her husband’s two older sons, Stewart said.

On the day of the explosion, the Fosters were scheduled to attend a training session for prospective parents. They were hoping to adopt a baby girl.

— Annie Gowen and Arthur Santana

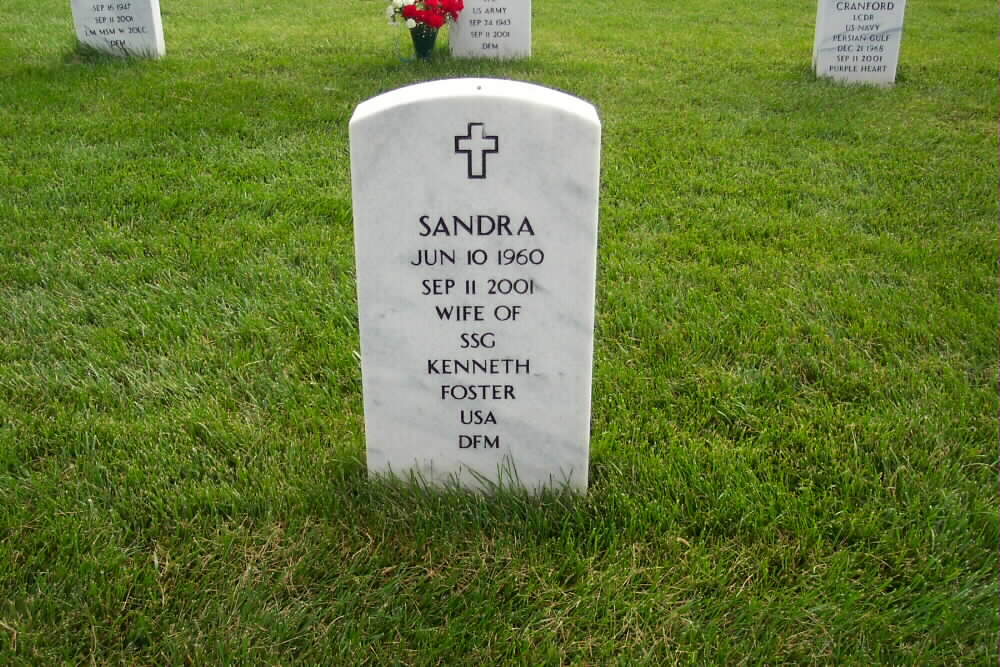

FOSTER, SANDRA HILL (DUTCHESS) FOSTER, suddenly on Tuesday, September 11, 2001 at The Pentagon, Arlington, Virginia. The beloved wife of Kenneth Foster; step mother of Kyle and Kellen Foster. Also survived by her mother, Barbara Hill, one brother, Lawrence Hill; mother-in-law, Charlotte Anderson; six sisters-in-law, three brothers-in-law, a host of other relatives and friends. The family will receive friends on Tuesday, October 9, at 10 a.m. until time of service at 10:30 a.m. at the Faith Hope Christian Center Church, 2001 Brooks Dr., Capitol Heights, MD. Interment Arlington National Cemetery.

Courtesy of the Washington Post:

A Spouse’s Journey From Despair to New Purpose

Friendship, Counseling Help Md. Man Decide To ‘Go On With My Life’

By Arthur Santana

Washington Post Staff Writer

Wednesday, September 11, 2002

The enormity of the loss hit him Thanksgiving day. Alone in his large, empty home in Clinton, Kenneth Foster climbed the stairs to his bedroom and took out a revolver. He loaded it with two bullets, spun the chamber, stuck the barrel in his mouth and pulled the trigger. The hollow click of an empty chamber resounded with urgency.

It was time to get help.

Until then, Foster says now, he had been in “deep denial” about September 11, the day he lost his wife, Sandra, nicknamed “Dutchess,” at the Pentagon. He had raced to the west lawn of the complex, arriving within 20 minutes of the attack, and stood before the raging fire as he desperately searched for her in the chaos.

Blending in with rescue workers and lying low, Foster remained there for two nights, his eyes secretly trained on a faraway open door. He expected that either she would emerge from her office in the E Ring or that he would rush in and save her. Even after an agonizing 44-hour vigil, with his wife still unaccounted for, he was convinced that she was alive.

About a month later, he had a memorial service. But it was hard to believe that Sandra, at 41, was really gone. Until Thanksgiving, when she wasn’t there to share dinner.

“I called a friend to come get the gun,” he said.

Foster is glad he didn’t die that day. People who commit suicide, he believes, don’t go to heaven, so he would never have seen his wife again.

Right after Thanksgiving, Foster said, he started to have trouble breathing. It was a soft wheezing at first. He had a history of lung problems, but they were never serious. Soon, though, the wheezing became gasps for breath, then a hacking cough that cracked two ribs.

“Her death triggered it,” he said. “Whatever it was, the stress brought it out.”

Foster, a retired Army sergeant on leave from his job as an Army policy analyst, was hospitalized in early December in the intensive care unit at Walter Reed Army Medical Center.

“I was very suicidal, emotionally distraught,” Foster said. “I was this 48-year-old man who just lost his wife. . . . I can hardly breathe, and these doctors are coming at me with masks and gloves. I thought it was all a nightmare.”

Doctors decided that a small hole in Foster’s lung was causing his shortness of breath. They eventually put a tube in his back and sent him home with a face cup and oxygen tanks to help him breathe.

Back from the hospital, Foster said, he retreated into “pity parties” and sank into crying fits that could last hours. His sons from an earlier marriage, Kyle, 25, and Kellen, 15, who live in Landover with his ex-wife, tried to comfort him. Kyle Foster came by

every day for a while, but his father felt that his children should be busy with work and school — and he wanted at that point to be by himself.

His sprawling home, once so full of love, became a house of tears, with his wife’s portrait staring down at him from above the mantel. A room made ready for two girls he and his wife were hoping to adopt sat empty. And despite his sons and some 500 sympathy cards piled up on his living room floor, he felt utterly alone.

Then one day last winter, 12-year-old Kelvin D. Moore, visiting his grandparents three doors down the block, passed by and thought he heard something strange coming from Foster’s home. He walked across the front lawn and peeked in the back yard. There was Foster, head in hands, sobbing.

Kelvin climbed the steps to the back porch and tried to console him.

“I said I knew he was sad because his wife had died,” said Kelvin, a thin, soft-spoken boy in glasses who smiles easily. “I told him that I’d do anything he wanted, that I was there to help.”

Foster lifted his head. It was the beginning of a remarkable friendship.

“I really, really needed him,” Foster said in a recent interview, crying as he recalled the boy’s kindness and concern. “Isn’t that amazing? Just a kid, and he wants to help me.”

For a time, to be close to his wife, Foster would go to Arlington National Cemetery, lie down on a blanket and fall asleep at her grave, careful not to be seen by the guards. It helped him, he said. As he awoke in the first light, it reminded him of those days

at the Pentagon, when sleep came in fits and being close to his wife was a solitary and private secret.

Now 49, Foster receives counseling twice a week and says that, at last, he is coming to terms with his wife’s death. He has an idea to honor her memory: a $25,000 annual Sandra Nadine Foster college scholarship for a senior girl from a District public

school. The scholarship, he said, will be awarded from his wife’s life insurance and the couple’s savings, about $227,000 — until the money runs out.

Foster said his wife, whom he met 15 years ago when both worked for the Defense Intelligence Agency, valued education above almost everything. The scholarship recipient will be chosen based on academic record and an essay on how Sept. 11

affected her. He hopes to present the first scholarship this fall and has a Web site about the award, www.sandranadinefoster.homestead.com.

Setting up the scholarship has become “the most important thing to me right now,” he said. “It’s my lifeline. . . . We can turn her tragic death into something special, and that’s what I want to do.”

In the year since his wife’s death, Foster said, he has shed his rough exterior, his cocky, domineering manner. He is working on being closer to his sons and wants to make more male friends — something his wife often encouraged.

Foster, a lapsed Baptist, said he also has recently refound his faith. He speaks often of love and God.

Recently, the tube jutting out of his back popped out. His doctor said that as long as he wasn’t having any trouble breathing, he should leave it out and see what happens.

“I know I’m healing,” Foster said.

Foster, a Fort Worth native who has lived in the Washington area since 1972, said he plans to return at the end of the month to his job in Alexandria. And he is looking forward this spring to resuming his part-time job as a basketball coach at Wakefield

High School in Arlington.

A few weeks ago, he was finally able to open a large envelope containing his wife’s dress, watch and jewelry, recovered from the Pentagon. The items smelled of burning fuel and smoke, bringing back the memories.

Just then, Kelvin came by.

“And he asked me if I wanted to talk about it,” Foster said. “And he gives me a big hug and says, ‘You just made one major move.’ “

He is convinced that his wife arranged for Kelvin to be his guardian angel on Earth. The two see each other all the time, playing video games, going to watch the Mystics play, bowling or just going to the grocery store.

Foster has put some of his wife’s things, including her watch, necklace and the wedding ring she wore for 11 years, in a large, lighted display case near the front door. He begins every morning with a prayer and a conversation with his wife at a candlelit

altar he has set up in the living room.

“I’ve cried a river since September 11,” he said. “. . . I’ll take it one day at a time. Things will work themselves out, all in time, but Dutchess will always be in my mind and in my heart.”

He has so far shunned the $1.9 million the U.S. government has offered as compensation for her death. His wife was a senior management officer at the DIA, and he can’t abide the requirement that other sources of income, including her monthly workers’ compensation survivor benefits, be subtracted from the total payout.

The monthly checks, he said, “let me know she worked for her country for 24 years, and I don’t want anyone taking that away.”

Today, he plans to attend the ceremonies at the Pentagon and Arlington National Cemetery, a day of saying goodbye all over again.

“I’ll be glad when the day comes and goes,” he said.

But after a year of mourning, Foster believes he has a new outlook on life and is optimistic about the future.

“I’m not interested in dying anymore,” he said. “I’ve got things to do.”

His son Kyle, who visits several times a week, says his father is “coming around now.”

“He’s not as emotional as before,” his son said. “He’s more sociable as far as people outside his family.”

Kenneth Foster said he’s had an image in his mind of a calendar in the road with a stop sign placed on today’s date. It’s been a long road to the September 11 anniversary, he said a few weeks ago, as the date drew closer.

“I know I’ll get to that stop sign, and God, I’m not looking forward to it, but I know I’ll reach it,” he said. “And I know I’ll have to cross the street and go on with my life, because that’s what my wife would have wanted.”

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard