Article published Jan 22, 2006:

Jim Schlosser

Courtesy of the News & Record

GREENSBORO — William McBryar was a military hero who lived in our midst in the early 1900s, unrecognized except by a few in the black community.

He had been one of the Buffalo Soldiers, black enlisted men in the segregated Army who fought Indians on the plains, the Spanish in Cuba and the Philippines and Mexican bandits along the border .

In 1890, McBryar, received what’s now the nation’s highest award for valor, the Congressional Medal of Honor. He was cited for heroism that year against the Apaches in Arizona.

Greensboro will get a chance to recognize McBryar this July when the national 9th and 10th Cavalry Association holds its annual convention at the Koury Convention Center. More than 500 people are expected to attend.

The association perpetuates the memory of the Buffalo Soldiers. The membership includes a few aging Buffalo troopers who served from the 1920s to the early 1940s.

The Buffalo Soldier era is defined by some as 1870 to 1916. But Henri LeGendre of Charlotte, state leader of the association, says the period lasted until early 1944. That’s when the original Buffalo Soldier units, the black 9th and 10th Cavalry and the black 24th and 25th Infantry regiments, disbanded. Judge Lawrence McSwain of Greensboro, who has done research on the Buffalo Soldiers, extends the ending date to 1952 when President Truman ordered the military integrated.

Most historians believe the Indians came up with the nickname. They respected the buffalo and admired the courage of the black soldiers, though they were the enemy.

Other historians say Indians coined the name because they thought the soldiers’ hair and skin color resembled the bison.

McBryar had 14 years of service with the Army when he moved here as a civilian in about 1906. The 1907-08 Greensboro City Directory puts McBryar at 918 E. Market St. and his wife, Sallie Waugh McBryar at 411 High St., off Lee Street. He was listed as a paver, she a nurse.

The 1912-13 City Directory has McBryar at 411 High St., his wife’s old address. There’s no mention of her. The directory said McBryar farmed, despite his city address.

The McBryars, in their 40s when they married, seemed part of the local black aristocracy. Their wedding — the first for both — at her family’s High Street home was conducted by the minister of St. James Presbyterian, one of the city’s oldest and most prominent black churches. Witnesses included the pastor of St. Matthews United Methodist and Jacob R. Nocho, a black civic leader for whom the Nocho Park neighborhood is named.

While here, McBryar tried repeatedly to return to the Army, despite advancing years. But his prior service and Medal of Honor weren’t enough for the Army brass.

Historian Frank Schubert, of Alexandria, Virginia, author of “Black Valor: Buffalo Soldiers and The Medal of Honor, 1870-1898,” says McBryar and another Buffalo Soldier and Medal of Honor winner, Edward Baker, “were probably the most distinguished soldiers of their generation.”

They fought in the most hostile and inhospitable regions — the torrid Mexican-Arizona border, the frigid Montana plains, the Philippine jungles, which McBryar despised, and Cuba. Their white commanding officers praised their courage, leadership and ability to overcome hardship. In Arizona, McBryar was injured when a horse fell on him. In Cuba, he contracted malaria.

He and Baker became frustrated fighters, seesawing up and down the enlisted ranks. McBryar once received a temporary commission and rose to first lieutenant. But the Army returned him to the enlisted ranks, despite his having three years of college and being fluent in Spanish.

“All they wanted, and which they were always denied, was a regular Army commission,” Schubert said in a telephone interview.

Without question, he said, race was the issue. The regular Army had only three black officers in 1900.

McBryar even hired a Washington lobbyist to make his case to the Army. His mother wrote President William McKinley on her son’s behalf, saying America’s black community looked up to black soldiers.

Schubert quotes black historian Rayford Logan as saying Buffalo Soldiers “were our Ralph Bunche, Marian Anderson, Joe Louis and Jackie Robinson.”

Schubert says McBryar “didn’t shrink from hostile fire and he knew how to direct his fire.” One reason he may have won the Medal of Honor was he found a way to make his gunfire penetrate and cause havoc inside the Apache caves.

McBryar had served 14 years when the Army mustered him out in 1901. It’s not clear what he did for the next three and a half years, but in 1904 at 44 he was allowed to rejoin the Buffalo Soldiers, with the rank of private in the cavalry.

Rheumatism traceable to the horse falling on him made life as a horse soldier impossible. The Army discharged McBryar after a year.

He came to Greensboro and married on December 6, 1906. Three years later, he left to work as a watchman at Arlington National Cemetery. He returned here to farm for two years, then spent a year as a military instructor at what’s now St. Paul’s College, a black institution in Virginia. From there, he worked at a federal prison in Washington state.

He was back in Greensboro by 1916. Now in his 50s, he volunteered again for the Army. Buffalo Soldiers were fighting Pancho Villa’s Mexican bandits. The Army rejected him.

A year later, as America prepared for World War I, he asked to serve as an infantry officer in Europe. Too old, the Army said.

In 1923, applying for a federal pension, he listed his address at Route 4, Box 140, which may have been what’s now Martin Luther King Jr. Drive through Pleasant Garden. He said his occupation was farmer.

He later moved to Lincolnton, near Charlotte, where in another pension application, he said he was 72 and still working. He wrote that his first wife had died and a second marriage failed.

With no one to care for him, he moved to Philadelphia and lived out his life with his sister. He died there March 8, 1941, at 80.

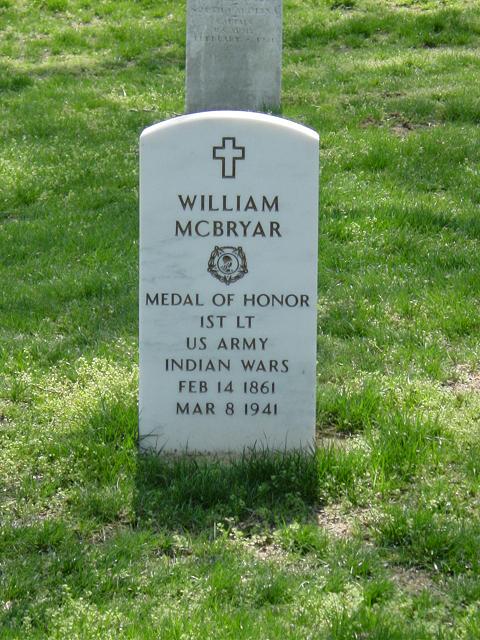

Schubert writes: “He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery, where he had once worked as watchman. The government provided a flag.”

Born in Elizabethtown, North Carolina on February 14, 1861, he was awarded the Medal of Honor for service in the Indian Wars as Sergeant, Company B, 10th United States Cavalry, in Arizona on May 11, 1889.

He died on March 8, 1941 and was buried in Section 4 of Arlington National Cemetery.

McBRYAR, WILLIAM

Rank and organization: Sergeant, Company K, 1 0th U.S. Cavalry. Place and date: Arizona, 7 March 1890. Entered service at: New York, N.Y. Birth: 14 February 1861, Elizabethtown, North Carolina. Date of issue: 15 May 1890.

Citation:

Distinguished himself for coolness, bravery and marksmanship while his troop was in pursuit of hostile Apache Indians.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard