Press reports: 31 March 2003:

Senator Moynihan Is Buried in Arlington Cemetery

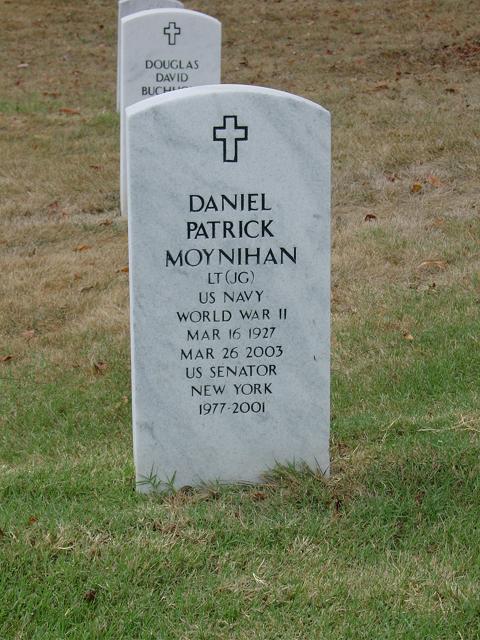

ARLINGTON, Va., March 31 — Daniel Patrick Moynihan, naval gunnery officer and four-term United States senator, was buried today at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors.

The graveside ceremony followed a funeral mass at St. Patrick’s Church, the oldest Roman Catholic church in Washington and the parish where Mr. Moynihan worshiped before his death last Wednesday at 76.

“Pat Moynihan was a man of quiet faith,” Msgr. Peter J. Vaghi told the mourners. “For him, this found expression in his long commitment to the body politic, the pursuit of the common good and his special care for the poor, the family structure and the most needy in our midst.”

The several hundred mourners included dozens of former aides, senators past and present, including Robert Dole, Charles E. Schumer and Hillary Rodham Clinton, and one prominent Bush administration figure, Donald H. Rumsfeld, the secretary of defense. Before they entered the sanctuary, mourners crossed a green marble shamrock embedded in the floor of the church vestibule.

After the mass, the hearse carrying Mr. Moynihan’s coffin made its way to the Russell Senate Office Building and then down Pennsylvania Avenue, whose revitalization he championed for four decades as an aide to Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon and Ford and then in 24 years as a senator from New York.

His burial place at Arlington was earned by his Navy service from 1944 to 1947. At the cemetery, a band played the “Navy Hymn” and led a horse-drawn caisson that was followed on foot by his widow, Elizabeth Brennan Moynihan, and their children, Maura, John and Timothy.

Seven sailors fired three rifle volleys. A bugler sounded “Taps.” The Navy Band played “America the Beautiful.”

Maura Moynihan read from Dylan Thomas:

“Do not go gentle into that good night,

“Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

“Rage, rage against the dying of the light. . . .”

She explained later that she chose the verse because her father knew Mr. Thomas and sometimes drank with him at the White Horse Tavern in Greenwich Village.

WASHINGTON? Even in death, Pat Moynihan continues to surprise. He is being laid to rest Monday not in a family plot somewhere in New York but in Arlington National Cemetery – with full military honors. How many of his admirers and constituents ever knew how proud he was of – barely out of high school – having served in the Navy at the end of World War II. Or that this man so well known for scholarship and politics would opt to spend eternity with soldiers and sailors.

That there’s no family plot also has to do with the fact that he grew up without much of a family. (He later acquired a remarkable wife and had three talented kids.) His father exited when Pat was 10, leaving a poor family in the throes of the depression. He really did shine shoes in Times Square and work on the docks. His mother did own a bar in Hell’s Kitchen. This man who devoted much of his career to family breakdown, poverty, welfare, and social disfunction knew such things up close.

And what a career it was. The political analyst Michael Barone once termed Pat the nation’s best thinker among politicians since Lincoln and its best politician among thinkers since Jeferson. What’s more, he was a gifted teacher, a man who nurtured the careers of hundreds, a discerning architecture buff and urban visionary, an expert on auto safety and Social Security, a diplomat of power and influence, a wit and raconteur, a social commentator with few peers – and on and on.

Perhaps more than anything else, he was a man of intellectual strength and integrity, who lived and breathed the maxim that “ideas have consequences” and who was unafraid to speak the truth, as he saw it, even to those who didn’t want to hear it.

That’s not so unusual a trait in tenured professors, which Pat also was from time to time. But of how many successful politicians can that be said? (New York’s fractious voters sent him to the US Senate four times.) Of how many ambassadors? (He held that post both in New Delhi and at the UN.) Or presidential advisers? (He served four presidents, including two years in Nixon’s White House.)

The norm in public life today is to tell people what they want to hear. The norm on Capitol Hill is a nice haircut atop a mind more attuned to polls and focus groups than data or ideas. The norm in diplomacy is to make nice, not to confront tyrants and abusers of human rights. The norm at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue is to tell the president things that please him. The norm in seech giving is to amuse and flatter one’s audience.

Pat violated all those norms – and rather enjoyed doing so. I’ve often thought of him as innately countercyclical, the personification of his influential essay entitled “The United States in Opposition.” It was not simply perverse, however, as in, “You say it’s raining and I’ll insist the sun is shining.” Rather, it was a deeper skepticism about the conventional

wisdom and wariness of oversimplification, a refusal to be swayed by the crowd if the data told him otherwise. One who knew him for four decades e-mailed me the other day, “He could stand off to the side of society, and see it as it really was, putting aside all the pretense. A spade, after all, was a spade.”

How Pat loved data – and how much more he saw in it than most of us do. For example, it was the simplest of data about the Soviet Union that led him, a decade ahead of the CIA, to predict the collapse of that regime. Where most of us would see a fact, he would spot the trend line. Where most of us would extrapolate into the near future, he would peer around the corner and glimpse the long-term consequences of the trend he’d found. Better than anyone I’ve known, he could imagine what wasn’t yet visible, whether a grand design for rebuilding Pennsylvania Avenue or the consequences for America’s black population if out-of-wedlock birthrates kept rising. Where most of us look out of one eye at statistics and out of the other at the world around us, Pat had a peerless ability to blend what he saw with what the numbers showed – and then explain that blend in vivid language so that the rest of us could begin to picture it.

This sometimes got him into trouble. Henry Kissinger didn’t like his candor at the UN, especially about the centrality of human rights. Lots of people were upset by his report on the “Negro family” – and again when he told Nixon that the issue of race itself might benefit from a period of “benign neglect.” Bill and Hillary Clinton were not at all pleased by his criticism of their signature healthcare plan. Indeed, there’s quite a list of occasions when his candor and integrity – and irreverence and puckishness – riled audiences, superiors, and interest groups.

But that didn’t deter him from speaking the truth as he understood it. And most of the time he turned out to be right.

Pat had his shortcomings. He could be vain and a bit pompous. He didn’t deal well with criticism. He sometimes took pleasure in being obscure. He got to the office late (though his productivity was staggering). And he was definitely not easy to work for.

Yet he attracted a marvelously talented cadre of helpers over the years – a large, bipartisan, and multiethnic club. It spans many fields of endeavor. And it’s full of people who attribute no small part of their own notable achievements to their apprenticeship with Daniel Patrick Moynihan. I’m proud to be one of them.

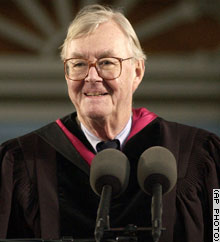

Chester E. Finn Jr., a former assistant secretary of education, is president of the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation and a senior fellow at Stanford’s Hoover Institution. He was a graduate student of Mr. Moynihan’s and also served with him at the White House, in New Delhi, and on his Senate staff.

Dozens of Washington’s most powerful lawmakers and dignitaries bid a sad farewell Monday to Daniel Patrick Moynihan, remembering the former Democratic senator as a visionary.

“You had Democrats and Republicans of three generations, all basically awed by Pat Moynihan,” said Senator Charles Schumer, a Democrat from New York. “They could have been 25, they could have been 85, they all knew what he did.”

Moynihan died last week at age 76, after complications resulting from an emergency appendectomy.

In his years of public life, Moynihan often courted criticism by warning of future problems before the rest of the country seemed willing to face them. He tackled issues ranging from the collapse of the Soviet Union to the weakening of the American family and the loosening of societal standards.

Monsignor Peter Vaghi, who presided over the funeral Mass at St. Patrick’s Church, said Moynihan was “a man of quiet faith.”

“For him, this found expression in his long commitment to the body politic, the pursuit of the common good, and his special care for the poor, the family structure, and the most needy in our midst,” Vaghi told about 700 mourners.

The mourners included dozens of lawmakers and other dignitaries from the decades Moynihan spent in public office, as an assistant to four presidents, an ambassador, and a four-term Democratic senator from New York.

The group included former Senators Bob Dole and Bill Bradley, Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan, Attorney General John Ashcroft and Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld.

During the Mass, Moynihan’s casket was draped by a simple white cloth, which was later replaced by an American flag.

The casket was followed by his widow, Elizabeth, their three children and two young grandchildren. The funeral procession traveled past the Capitol and down Pennsylvania Avenue, and then across the Potomac River to Arlington National Cemetery.

Moynihan, who served in the Navy from 1944-47, was buried with military honors, including a seven-member Navy firing party.

From press reports: Thursday, March 27, 2003

Friends and family of Daniel Patrick Moynihan will gather Monday morning to say farewell to the beloved senator, who died Wednesday at age 76. The Rev. Peter J. Vaghi will officiate at a private funeral Mass in downtown Washington’s St. Patrick’s Catholic Church. Afterward, Moynihan, a former naval gunnery officer, will receive a full-dress military burial at Arlington National Cemetery. The pallbearers will include Moynihan’s sons, Tim and John, and several former chiefs of staff: newsman Tim Russert, Tony Bullock, Bob Peck, Lawrence O’Donnell, Peter Galbraith and Richard Eaton.

WASHINGTON, D.C. — Former Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a Democrat from New York who enjoyed a reputation as an intellectual giant among his peers, died Wednesday after battling an infection stemming from a ruptured appendix. He was 76.

His death was announced on the Senate floor by Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton, who was elected to his seat after he retired.

“We have lost a great American, an extraordinary senator, an intellectual and a man of passion and understanding about what really makes this country great,” Clinton said.

Moynihan’s appendix ruptured March 10 and he was taken to Washington Hospital Center for an emergency appendectomy. On March 14, he was moved to the intensive care unit, where he was treated for an infection, pneumonia and low blood pressure, a family spokesman said.

A scholarly man with the air of a rumpled professor, Moynihan had a variety of interests. He was one of the earliest proponents of welfare reform, writing an article in 1965 about the breakdown of African-American families. He was an expert on foreign affairs and was also a champion of urban redevelopment.

In his distinctive cadence, Moynihan held forth on a variety of subjects on the Senate floor. The Almanac of American Politics once described him as “the nation’s best thinker among politicians since Lincoln and its best politician among thinkers since Jefferson.”

He served in the Senate for four terms, from 1977 to 2001.

“Senator Moynihan was an intellectual pioneer and a trusted advisor to presidents of both parties,” President Bush said in a statement.

“Representing the people of New York for 24 years, Senator Moynihan was a leader in the Senate and was recognized for his commitment to free trade, Social Security, freedom for people around the world, and equal opportunity for all Americans. He committed his life to service and will be sorely missed.”

Moynihan was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, but grew up in New York. He worked as a shoeshine boy, graduated from a Harlem high school, worked as a longshoreman and served in the U.S. Navy during World War II before becoming a scholar and politician.

He was a Fulbright Scholar at the London School of Economics and received a doctorate from Tufts University’s Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. As a professor at Syracuse University in the 1950s he often published essays and reports about political and social issues.

New York’s other senator, Democrat Charles Schumer, paid tribute to Moynihan’s intelligence and eloquence.

“I know that I will be looking up to the heavens for inspiration,” Schumer said.

Moynihan worked for John F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign and went to work for the Labor Department in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, becoming assistant secretary for policy planning and research before leaving in 1965.

In 1965, Moynihan wrote “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action,” in which he emphasized the connection between fatherless families and increased welfare rolls. Though either ignored or criticized when first published, the study led to the 1988 Welfare Reform Act, which recognized for the first time a father’s duty to support his children and encouraged workfare initiatives.

Though a Democrat, he served as the U.S. ambassador to India and to the United Nations during the Nixon and Ford administrations.

In 2000, President Clinton awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

A funeral Mass is scheduled for Monday at St. Patrick’s Church in Washington, a family spokesman said. Burial will follow at Arlington National Cemetery.

Moynihan is survived by his wife of 47 years, Elizabeth Brennan Moynihan; three children, Timothy Patrick, Maura Russell, and John McCloskey Moynihan; and two grandchildren.

“His wife Elizabeth, daughter Maura, and sons Timothy and John were with him throughout his time in the hospital,” a statement from the family said.

Former New York Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a liberal Democrat who questioned liberal dogma, died yesterday. He was 76.

Senator Moynihan died of complications from a ruptured appendix at 4:15 p.m. at the Washington Hospital Center, hospital officials said. He underwent surgery March 11 to remove the appendix, but afterward developed an infection and pneumonia.

Widely respected for his social-policy writings, Mr. Moynihan served the administrations of John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. New York’s current senators, both Democrats, paid tribute to him from the Senate floor yesterday afternoon.

“We have lost a great American, an extraordinary senator, an intellectual and a man of passion and understanding about what really makes this country great,” said Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton, who succeeded Mr. Moynihan in 2001.

Senator Charles E. Schumer said, “His life was a testament to the fact that one man who just thinks can make a difference to society.”

Praise from the other side of the aisle was equally effusive, with former Senate Republican Leader Trent Lott of Mississippi saying: “I have not known a more brilliant or more erudite senator.”

President Bush said in a statment: “Senator Moynihan was an intellectual pioneer and a trusted adviser to presidents of both parties. … He committed his life to service and will be sorely missed.”

“In establishing himself as one of our nation’s most eloquent voices in the quest for a more civil society, Senator Moynihan was the very example of what a statesman should be,” said former New York Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani.

The Almanac of American Politics called Mr. Moynihan “the nation’s best thinker among politicians since Lincoln, and its best politician among thinkers since Jefferson.” Columnist George Will once said Mr. Moynihan has written more books (18) than most senators have read.

His office said a funeral Mass is scheduled for Monday in Washington, and he will be buried that day with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery.

A bow-tied academic whose erudition and courtly manner gave little hint of his working-class roots in New York’s Hell’s Kitchen, Mr. Moynihan wrote a seminal report on poverty in 1965 that exposed a deep fracture in the liberal coalition.

In “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action,” Mr. Moynihan wrote: “At the heart of the deterioration of the fabric of Negro society is the deterioration of the Negro family.”

In his report, Mr. Moynihan — then a 38-year-old Assistant Secretary of Labor in the Johnson administration — said “the steady expansion” of welfare programs “can be taken as a measure of the steady disintegration of the Negro family structure over the past generation in the United States.”

The reaction was furious. Martin Luther King warned that what became known as “the Moynihan Report” would be “used to justify neglect and rationalize oppression.” Mr. Moynihan was accused of racism and “blaming the victim,” and soon left the administration to accept an academic post at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“The liberal Left can be as rigid and destructive as any force in American life,” he wrote in 1967.

It was not until the 1990s that elite opinion accepted Mr. Moynihan’s conclusions, influencing the 1996 Welfare Reform Act — although the New York senator voted against that bill.

Born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Mr. Moynihan soon moved with his family to New Jersey, but he spent most of his childhood in a working-class New York neighborhood. After his alcoholic father died when he was 10, he sold newspapers, shined shoes and worked on the docks.

Graduating from East Harlem’s Benjamin Franklin High School, Mr. Moynihan attended City College before enlisting in the Navy in 1944. He graduated from Tufts University, added master’s and doctoral degrees and attended the London School of Economics as a Fulbright scholar.

Entering political life as a speechwriter for New York Governor W. Averell Harriman in 1954, he went to Washington to join the Kennedy administration in 1961. After his election to the Senate in 1976, Mr. Moynihan tended to move left or right to counterbalance the administration.

When Democrat Jimmy Carter was president, Mr. Moynihan called the administration’s foreign policy weak and naive, and said: “A party of the working class cannot be dominated by former editors of the Harvard Crimson.” But during the Reagan years, Mr. Moynihan called for a nuclear freeze and blasted the administration for deficit spending.

Liberals would later blame Mr. Moynihan for the defeat of the Clinton administration’s health care plan.

As chairman of the powerful Senate Finance Committeee, Mr. Moynihan appeared on NBC’s “Meet the Press,” on September 19, 1993 — three days before President Clinton was to deliver his speech calling for universal health insurance — and said there was “no health care crisis.” He dismissed as a “fantasy” the administration’s claims that its plan would save $91 billion.

WASHINGTON – Former Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a New York City shoeshine boy who became an iconoclastic scholar-politician and served four terms in the Senate, died Wednesday. He was 76.

Moynihan’s death was announced on the Senate floor by Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton, who two years ago was elected to the Senate seat Moynihan had held for 24 years.

“We have lost a great American, an extraordinary senator, an intellectual and a man of passion and understanding for what really makes the country work,” she said.

The New York Democrat died from complications stemming from a ruptured appendix at 4:15 p.m. Wednesday at the Washington Hospital Center, hospital officials said. He had undergone surgery March 11 to remove his appendix and was moved into intensive care later that week, suffering from infection and pneumonia.

The lanky, pink-faced lawmaker, who preferred bow ties and professorial tweeds to the Senate uniform of lawyer-like pinstripes, reveled in speaking his mind and defying conventional labels.

Known for his ability to spot emerging issues and trends, Moynihan was a leader in welfare reform and transportation initiatives and an authority on Social Security and foreign policy.

His intellect and his emphasis on principle before politics won him the respect of both parties. In more than 30 years of watching the Senate, former Senate Republican leader Trent Lott of Mississippi said: “I have not known a more brilliant and a more erudite senator.”

President George W. Bush described Moynihan as an “intellectual pioneer” who was “recognized for his commitment to free trade, Social Security, freedom for people around the world and equal opportunity for all Americans.”

Senate Democratic leader Tom Daschle of South Dakota said that “in many respects, Pat Moynihan was larger than life,” citing a description in the Almanac of American Politics that Moynihan was “the nation’s best thinker among politicians since Lincoln and its best politician among thinkers since Jefferson.”

A Mass is scheduled for March 31 in Washington, D.C., and he will be buried that day with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery. Moynihan served in the Navy from 1944 to 1947.

Moynihan was a senator from 1977 to 2001. After retiring from politics, he became a senior scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center.

He stayed active in politics, from campaigning for Sen. Clinton to his recent work as co-chairman of Bush’s Social Security commission.

Moynihan established his academic credentials early, teaching economics and urban studies at Harvard.

Daschle noted that Moynihan was the only person in history to serve in a Cabinet-level or sub-Cabinet-level position in four successive administrations, from Kennedy through Ford.

He served as ambassador to India from 1973 to 1975. As U.S. ambassador to the United Nations in 1975 and 1976, he beat the drum of anticommunism and demanded that other countries temper their anti-U.S. rhetoric if they wanted American help.

His unyielding support of Israel made him popular with New York’s Jewish population, and his televised statements at the United Nations elevated him to near-celebrity status.

Hoping to win a Senate seat in 1976, Moynihan emerged the winner of a bitter five-way Democratic primary. In the general election, he defeated incumbent Republican James Buckley by portraying him as out of touch with New York City’s fiscal crisis.

Moynihan’s fascination with global affairs never waned, and he continued to speak and write about world events, at one point foretelling the collapse of the Soviet Union.

“The Soviet Union is a seriously troubled, even sick society,” he said in a January 1980 speech on the Senate floor. “The defining event of the decade might well be the breakup of the Soviet empire.”

With a staccato delivery that emphasized unexpected syllables, Moynihan’s speaking style was often mimicked. He wrote or edited 19 books – more, it was said, than some of his Senate colleagues had read.

During his years in the Senate, Moynihan became a champion of many of the liberal programs he had once questioned, defending public jobs programs and fighting to increase federal aid to help offset New York’s crushing welfare burden.

In 1988, Moynihan, long one of the nation’s foremost authorities on work and family, helped bring together conservatives and liberals to enact the Family Support Act, a major revision of the nation’s welfare laws.

Born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Moynihan was the eldest of three children.

He spent his early childhood in Indiana, before moving to New York City.

The Moynihan children were raised by their mother after their father deserted the family when Pat was just 10. To help provide money for the family, Moynihan became a shoeshine boy. As a teenager, he first heard of the attack on Pearl Harbor while working on a customer’s shoes outside Central Park.

Moynihan and his wife, Elizabeth Brennan Moynihan, had three grown children, Timothy, Maura and John. They spent summers at his farm in the upstate hamlet of Pindars Corners, where he liked to write in a nearby one-room schoolhouse.

Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a former Democratic senator, ambassador and presidential adviser known for his scholarly intellect, has died. He was 76.

“In many respects, Pat Moynihan was larger than life,” said Senate Democratic leader Tom Daschle, leading tributes on the Senate floor to the man who from 1977 to 2001 was one of the body’s most beloved and respected members.

Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton, who two years ago succeeded Moynihan in the New York Senate seat, announced his death on the Senate floor. “We have lost a great American, an extraordinary senator, an intellectual and a man of passion and understanding for what really makes the country work,” she said.

Moynihan died Wednesday at the Washington Hospital Center from complications stemming from a ruptured appendix. In declining health recently, he had undergone surgery to have his appendix removed on March 11.

During his 24 years in the Senate, lawmakers from both parties turned to the gangly, professorial Moynihan for his expertise on welfare issues, transportation, Social Security and foreign policy.

“Rising from the depths of Hell’s Kitchen in New York,” said Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist, R-Tenn., “he became one of America’s true leading intellectuals, whose foresight and whose ability brought to public attention a mass of critical issues long before others even realized these issues existed.”

“I just hope God gives us a few more Pat Moynihans in this Senate, and in this country,” fellow New York Democrat, Senator Charles Schumer, said.

In 2000, Moynihan received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

Born March 16, 1927, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, he became a shoe shine boy in New York City to help make ends meet after his father deserted the family when Moynihan was 10. He graduated from Benjamin Franklin High School in East Harlem and attended the City College of New York for one year before enlisting in the Navy, serving on active duty from 1944 to 1947.

He later graduated from Tufts University, studied at the London School of Economics as a Fulbright Scholar and taught government at Syracuse University and Harvard University. He was the author or editor of 19 books.

He was named an assistant labor secretary in the Kennedy administration and went on to become the first person ever to serve in a Cabinet or sub-Cabinet position in four consecutive administrations, from Kennedy through Ford.

As President Nixon’s urban affairs adviser, he proposed a policy of “benign neglect” toward minorities that drew heavy criticism. A 1965 report to President Johnson created a major policy flap when he warned that the rising rate of out-of-wedlock births threatened the stability of black families.

Moynihan saw himself at the time as a liberal observer warning of future problems. Rather than hearing praise, he was denounced as promoting racism. The controversy haunted Moynihan for years and resurfaced as late as the 1994 elections.

Representative Charles Rangel, D-N.Y., a leader of the congressional black caucus (news – web sites), said Wednesday that Moynihan “stood up for the poor, the underserved and the children when they had few other advocates.”

There used to be two framed magazine front pages in Moynihan’s Senate office. One was The Nation from 1979, titled “Moynihan: The conscience of a neo-conservative.” The other was a 1981 issue of The New Republic, “Pat Moynihan, neo-liberal.”

Moynihan, said President Bush, was “an intellectual pioneer and a trusted adviser to presidents of both parties.” Under Bush, he served as co-chairman of the Commission to Strengthen Social Security.

Moynihan was ambassador to India from 1973 to 1975, and his wife of 47 years, Elizabeth Brennan Moynihan, is an architectural historian specializing in classic Indian architecture. He was U.S. ambassador to the United Nations in 1975 and 1976.

He won the New York Senate seat in 1976, defeating incumbent Republican James Buckley by portraying him as out of touch with New York City’s fiscal crisis. But his interests went far beyond state politics, and his fascination with global affairs never waned. At one point he foretold the collapse of the Soviet Union.

“The Soviet Union is a seriously troubled, even sick society,” he said in a January 1980 speech on the Senate floor. “The defining event of the decade might well be the breakup of the Soviet empire.”

During his years in the Senate, Moynihan became a champion of many of the liberal Democratic programs he had once questioned, defending public jobs programs and fighting to increase federal aid to help offset New York’s crushing welfare burden.

In 1988 Moynihan helped bring together conservatives and liberals to enact the Family Support Act, a major revision of the nation’s welfare laws.

After retiring from politics, Moynihan became a senior scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center.

Moynihan, survived by his wife and three children, is to be buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery on Monday.

Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a dockworker and bartender who rose from poverty to become a four-term senator from New York and the leading scholar-politician of his time, died yesterday in Washington. He was 76.

The popular Democrat had been hospitalized three times since January, most recently for an emergency appendectomy and infection March 11. His condition worsened, and he died at 4:15 p.m. yesterday.

Across a colorful and sometimes controversial career, Moynihan advised four Presidents and was a United Nations ambassador, Harvard professor, author and the Senate Finance Committee’s first New York chairman in 155 years.

Columnist George Will wrote that Moynihan authored more books, 19, than some senators read. It was a tribute to Moynihan’s thinking on race, poverty and foreign affairs that influenced public policy for 40 years.

In their 1963 book “Beyond the Melting Pot,” Moynihan and Nathan Glazer erased conventional wisdom by showing that Americans retain their ethnic allegiances rather than fully assimilate.

In 1993, he argued that tolerance of petty crime created a climate for more misconduct. This attack on “defining deviancy down” became a foundation of former Mayor Rudy Giuliani’s anti-crime strategy.

Moynihan caused his biggest stir with a 1965 report that argued illegitimate births and fatherless homes were a cause of the crime and poverty plaguing blacks. He was criticized again in 1970 for a memo that advised then-President Richard Nixon to follow a policy of “benign neglect” on race issues.

The episodes strained relations with civil-rights leaders. Still, Moynihan would become one of New York’s most popular pols, winning a second term by 1.5 million votes ? a record for an off-year election.

Part of his appeal was that he defied easy labels. A New Deal liberal in the 1950s, he dabbled in neoconservativism before returning to mainstream Democratic thinking in the 1980s and ’90s. Yet as his final term ended, he suggested ending the New Deal, saying it was unfairly draining money from New York ? a fact he documented in yearly reports that showed how much more New York sent to Washington than it got back.

“You will never understand Pat in terms of commitment to left or right,” economist John Kenneth Galbraith once said. “His long-term commitment is to the cities, to the poor and especially to poor children.”

A cherubic 6-foot-4, Moynihan favored fine (if rumpled) English suits, liked a drink and spoke in staccato bursts. He could turn a conversation into a tutorial that bounced like a pinball from topics as diverse as the building of the Erie Canal to the history of trade with Mexico. But he was not without critics who complained that his legislative record never reached the heights of his rhetoric.

Part of the Moynihan legend is that he was raised in Hell’s Kitchen. He wasn’t. But hard times were a frequent companion.

He was born into middle-class comfort in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1927, the oldest of three children. After a move to New York’s suburbs, Moynihan’s hard-drinking dad abandoned them. Young Pat was 10. Frequently in financial straits, the family lived in cold-water flats in Manhattan. By age 21, he had been a shoeshine boy, stevedore and bartender.

Academic star

He graduated first in his class at Benjamin Franklin High School in Harlem but, lacking money, he went straight to work on the docks. He eventually made his way to City College, the Navy (from 1944-47), Middlebury College, Tufts and, on a Fulbright Scholarship, the London School of Economics.

Moynihan entered public service in 1955, as a top aide to Governor Averell Harriman (D-N.Y.). His work there produced another life-long passion, a romance with Harriman aide Elizabeth Brennan that blossomed into a 47-year marriage.

Favoring ideas over partisanship, Moynihan went on to advise Republican and Democratic Presidents, mixing public service with academia. His first run for public office ended in defeat, he lost a primary for New York City Council president in 1965.

He was assistant labor secretary under former Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. “Heavens, Mary, of course we’ll laugh again. It’s just that we’ll never be young again,” he told the columnist Mary McGrory after Kennedy’s assassination.

Angering liberals, Moynihan was Nixon’s chief domestic policy adviser. But it was a 1975-76 stint as UN ambassador that launched his political career.

Believing the United States should be more assertive at the world body, he called Uganda’s Idi Amin a “racist murderer” and denounced as “obscene” a resolution that called Zionism racism.

He won a following, and with a slogan of, “He spoke up for America, he’d speak up for New York,” Moynihan ran for Senate in 1976. He edged Bella Abzug in a five-way primary and beat GOP Sen. James Buckley 54% to 45%.

For all his work in the Senate, Moynihan’s hallmark legislation was a 1991 transportation bill that poured huge amounts of money into New York. He was content to let former Sen. Alfonse D’Amato (R-N.Y.) be Senator Pothole. Their odd-couple pairing led to the observation that if you wanted a lecture on immigration, see Moynihan. If you wanted a visa, see D’Amato.

Moynihan’s forte, as it was across his career, was identifying emerging issues and swaying others through his thinking.

Before Ralph Nader, Moynihan said improving car designs would cut traffic deaths. He forecast Social Security’s fiscal woes and the Soviet Union’s collapse. His passion for civic architecture fueled the ongoing effort to turn the Eighth Ave. post office into a grand new Penn Station.

Not always perfect

Moynihan could be famously wrong. “Shame on the President,” he said when Bill Clinton signed the 1996 welfare overhaul. Moynihan warned that the tough law would throw millions of hungry kids into the streets. That hasn’t happened.

The episode was part of a testy relationship with the Clintons. There was some irony, then, when Moynihan gave his blessing to First Lady Hillary Clinton’s bid for his seat when he declined to seek a fifth term.

Like a father escorting his daughter to the altar, Moynihan walked with Clinton on his farm in upstate Pindars Corners to the news conference launching her candidacy July 7, 1999. A Democrat said the passing-of-the-torch imagery that sunny day was worth 1 million votes for Clinton.

Standing on the floor of his beloved Senate, it was Clinton who announced Moynihan’s death yesterday.

Moynihan is survived by his wife and children, Timothy, Maura and John.

He will be buried Monday with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery in Washington. Originally published on March 26, 2003.

he casket of Sen. Daniel P. Moynihan rest at the front of the Church of St. Patrick in

Washington during a memorial service, Monday, March 31, 2003. Dozens of Washington’s

most powerful lawmakers and dignitaries bid a sad farewell Monday to Daniel Patrick

Moynihan, remembering the former Democratic senator as a visionary who never forgot

his humble roots.

Elizabeth Brennan Moynihan, back left, walks with pall bearers as they

accompanythe casket of the late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, D-N.Y., during a

memorial at the Church of St. Patrick in Washington, Monday, March 31, 2003

Pallbearers walk the casket of Sen. Daniel P. Moynihan out of the church of

St. Patrick in Washington, March 31, 2003.

Pallbearers move the flag drapped coffin of former Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan

after funeral services at St. Patrick’s Church

Maura Russell, daughter of Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan receives a hug as

she departs a memorial service for her dad at the Church of St. Patrick in Washington.

Elizabeth B. Moynihan, center, widow of late Senator Patrick Moynihan,

embraces a flag from the former Senator’s casket as grandaughter, Zora Moynihan,

left, and grandson Michael Patrick Moynihan, right, look on, Monday, March 31,

2003, at Arlington National Cemetery.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard