Sergeant First Class Paul Ray Smith: A Real Soldier’s Soldier

By Zeno Gamble

Special to American Forces Press Service

April 6, 2005

Over the past two days, I have spent quite a bit of time with the family of Army Sergeant First Class Paul Ray Smith. His German-born wife Birgit, their son, David, and their adopted daughter, Jessica, arrived in town April 3. Members of his extended family from Germany also are here, plus a handful of his fellow soldiers who served with him in Iraq.

It has been two years since Smith was killed in action, firing a .50-caliber machine gun from atop a broken-down armored personnel carrier in a courtyard where he had been instructed to build a containment facility for detainees near the Baghdad airport. His actions that day saved more than 100 of his fellow soldiers.

We all gathered in Washington for the presentation of the Medal of Honor to Smith’s son, 11-year-old David.

My friend Ernie Stewart and I had both been invited to join the Smith family. Stewart heads an organization named “Let’s Bring ‘Em Home.” We had been helping reunite service members and their families for Christmas holidays over the years. We had done what we could in helping to take care of the family since Smith’s death, and were invited to take part in the ceremonies.

David was a trooper like his father. As he stood next to his mother and his sister at the White House, David received the medal from the president. His face reflected the solemn mood of the ceremony, and his Aunt Lisa and Uncle Brad predicted that he would indeed grow up to be like his father. Later, he proved that his childhood was still intact, and he chatted freely of videogames and cartoons.

Jessica seemed distant at times, but was not shy. It appeared to me that her father’s sudden recognition had affected her life, and in a positive way. When the soldiers rolled up their sleeves to show off, she showed off her own Celtic design on her lower back.

Birgit remained in the highest of spirits throughout it all. Each ceremony brought her to tears, but when she spoke I could see that her words were full of pride for her husband. Her smile never wavered, and she was strong. It was with a grin when she showed off her tattoo. A red heart containing the name “Paul Ray” was emblazoned on her left arm under the words “You’re still Number 1.”

John Boxler also was there. The young man from Johnstown, Pennsylvania, had offered to become David’s pen pal, knowing firsthand what it’s like to lose a father. Boxler’s father, Army Sergeant John Boxler Sr., had been killed when a Scud missile struck his camp in Saudi Arabia during Operation Desert Storm. The Smith family asked Boxler to join in attending the April 5 ceremony at the Pentagon. The visit would complete his desire to visit all three places where the 9/11 terrorist attacks occurred.

Specialist Michelle Chavez was there. She was the medic who worked on Smith after he was shot in the head. Chavez had attempted to remove his helmet to treat him, but found that the helmet was holding his head together. She worked for 30 minutes trying to save him.

Private First Class Michael Seaman was there. He had been the driver of the armored personnel carrier. He was the guy injured by a rocket-propelled grenade who did his best to keep feeding Smith ammunition during the battle. He wore an Army Commendation Medal with a valor device on his uniform.

Specialist Louis Berwald was there. He had been manning the .50-caliber machine gun on the APC before it was struck with a mortar, inflicting injuries to his face, shoulder, and hand. He was evacuated from the courtyard and later received the Army Commendation Medal with valor device and a Purple Heart.

Sergeant Matt Keller was there. He had crossed the courtyard with Smith where a Bradley fighting vehicle knocked down a gate so they could engage the enemy. He followed Smith through, firing AT-4 rockets and his weapon at enemy positions and then returned through the breach while Smith fired the .50-caliber machine gun from the armored personnel carrier. He received a Bronze Star with valor device.

Sergeant Derek Pelletier was there. He had been firing anti-tank rockets at enemy positions alongside his boss. Knowing Smith almost four years, he was a loyal and dedicated subordinate. Pelletier was awarded the Bronze Star for his action in that battle. He was awarded another Bronze Star for heroism in a later battle where he saw Smith’s replacement hit by enemy fire. When he tried to pull him from the battlefield, he discovered that his boss had been cut in half. After duty in Iraq, he was admitted to the hospital for five months and then released from active duty to return to his home in Boston.

Enshrined in the Hall of Heroes at the Pentagon, Smith joined the brotherhood of soldiers whose true valor Americans rarely see. Birgit spoke in the hall, her red-heart tattoo visible under the see-through sleeves of her blouse.

Steadying her voice and holding back tears, Birgit told us that not only was her husband tough on his troops, but also on himself. That was reflected in his ideals.

“American soldiers liberated the German people from tyranny in World War II,” she said. “Today, another generation of American soldiers has given the Iraqi and the Afghan people a birth of freedom. This is an ideal that Paul truly believed in.”

Before finishing, she said she knew her husband would be proud that she had finally started the process to become an American citizen. Everyone in the Hall of Heroes applauded loudly.

It is an understatement to say that when a soldier read Smith’s citation aloud, citing his “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty” I got choked up. Army Major Al Rascon, a Vietnam War Medal of Honor recipient, standing next to me with his wife, Carol, had tears in his eyes and couldn’t speak a word. Smith’s battle buddies also were silent. You could hear them sniffing as each tried to hold back tears.

I felt honored that Birgit had asked me to join the family and guests. The ceremonies at the White House and the Pentagon were a prelude to a final ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery, where the sound of “Taps” brought the world to a standstill and everyone to a moment of closure. It is the saddest song in the world.

After the official ceremonies were over, about 20 of us — family, friends, and soldiers – gathered in the lounge at the Washington Hilton and talked late into the night about life, the world, politics, religion, weather and death. The somber voices faded away as we drank beer and schnapps and brandy. Cigarette smoke wafted about as the frowns slowly turned to smiles, then laughter, as we noticed the gathering had become an impromptu wake.

Birgit’s nephew Mathias shared a brew with his father and me as we talked about the overwhelming emotions of the past two days.

“You know, back home in Germany, I can only hope to see the Bundeschancellor on television,” he said. “But when our family comes to America, we are greeted by the president. This is indeed a funny situation.”

As the evening turned late, and our energy waned, we all parted ways. We exchanged hugs, addresses, phone numbers, and e-mail addresses. We had all been drawn together by a single tragedy resulting from an attack on our nation, and we each had to deal with the events that had led us to this time and place.

A terrorist attack, a soldier’s unwavering duty to his country, the loss of a loved one — such things are difficult to totally comprehend.– Yet from such tragedies one cannot help but feel pride. As we separated and made one last toast to Paul Ray and to Birgit, I wondered where each of us was going and if any of us would see one another again.

We knew where Birgit was going. She was going on to New York to see the World Trade Center site. She said she wanted to see what her husband had died for. I hope that the others in our group also find the closure in our lives where Paul Ray Smith had once been.

(Zeno Gamble is a writer in the Executive Secretariat at the Pentagon.)

HOLIDAY, Florida, May 27, 2006:

Rita Richardson smiles at the memory: Her young son Dan, prowling the woods dressed in camouflage and green face paint or jumping off the shed like a paratrooper. But she wanted her little commando to know that war was more than a game.

So each Memorial Day, she would take him to Arlington National Cemetery, near their Virginia home, to walk with her through that “garden of stone,” to appreciate the sacrifices honored there. This Memorial Day, she will be there in spirit as her soldier son trains for another overseas deployment.

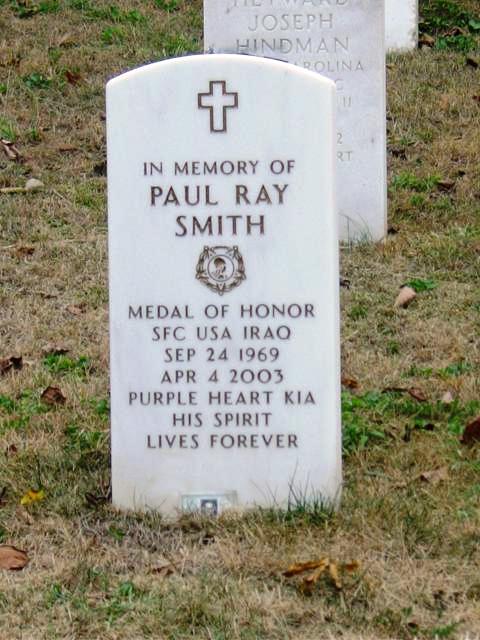

Janice Pvirre will be at Arlington in person. She will join the other “Gold Star Mothers,” those who have lost children in combat, to lay a wreath and to say a prayer at a white marker engraved with the emblem of this nation’s highest military honor.

Her son, Sergeant First Class Paul R. Smith, died in a dusty courtyard outside Baghdad, fatally wounded in a furious firefight while showing “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity … above and beyond the call of duty” a sacrifice that made him the only service member awarded the Medal of Honor in the Iraq war.

Among those Sergeant Smith’s actions saved: Dan Richardson, who has recently married and himself been promoted to Sergeant.

That knowledge is both a blessing and a burden, for one mother to know that any milestone she will celebrate with her son a birthday, a holiday, the birth of a child was made possible by another mother’s loss.

“We have been drawn together for some reason, and we’re both intrigued about that reason,” Richardson says. “There is a destiny behind all of this. And it’s not over. It’s not played out yet. We don’t know where it’s going from here.”

Janice Pvirre believes her son’s fate was determined when he was 5.

One day, someone at school asked Paul what he wanted to do when he grew up. “I’m going to go in the Army,” the green-eyed boy declared, looking up through long lashes. “And I’m gonna have babies and I’m gonna get married.”

“I said, `Well Paul. Let’s rearrange that,'” his mother laughingly recalled recently by the pool at her daughter-in-law’s home in Holiday, north of Tampa. “`Go in the military, get married and THEN have your babies.’ And he laughed and said, `Yeah.'”

He did join the Army, in 1989, but at first he wasn’t much of a soldier. Stationed in Germany, Smith drank too much and, on a couple of occasions, slept right through formation.

The first Gulf War changed him, his mother says.

The man who once partied late into the night had become obsessed with training and discipline. He drilled his soldiers well into the night and was even known to swab the muzzles of their rifles, looking for dirt. The men took to calling him the “morale Nazi.”

Smith, who had married shortly after that war in 1992 and had become a stepfather, then a father, told his wife that he feared he hadn’t seen the last of Iraq. Making sure his men were ready became a priority, Birgit Smith says.

“He said, `We are not done. We’re going back. We didn’t finish,'” the young widow says. “It was just a matter of time.”

That time came in March 2003. And Smith was ready.

“There are two ways to come home, stepping off the plane and being carried off the plane,” he wrote in a letter to his parents. “It doesn’t matter how I come home because I am prepared to give all that I am to ensure that all my boys make it home.”

One of those “boys” was Dan Richardson.

Growing up around Washington, D.C., Dan Richardson was surrounded by the military.

Jerry and Rita Richardson were both federal employees. Jerry Richardson had served four years as a Navy parachute rigger, and the couple always stressed service to country.

When Dan was about 12, his mother took him to a gathering of World War II veterans, where, as a National Archives official, she’d been asked to give a speech on that war’s most decorated hero Audie Murphy.

She had regaled her son with tales of the young soldier who climbed onto a burning tank and, firing its .50-caliber machine gun until he ran out of ammunition, killed or wounded more than 50 attacking Germans. His deeds earned Murphy the Medal of Honor in 1945 and inspired the movie “To Hell and Back,” in which he starred as himself.

Young Dan helped gather signatures on a petition for a postage stamp honoring Murphy.

Like Smith, Dan was an indifferent student. He liked fast cars and skydiving “a thrill seeker from day one,” his mother says.

When he was 17 1/2, Dan asked his parents for permission to join the Army. They happily signed his papers.

Dan wanted Airborne, but ended up at Fort Stewart, Ga., with B Co. of the 11th Engineer Battalion, part of the 3rd Infantry Division.

Audie Murphy’s division.

And now, Paul Smith’s division.

On April 4, 2003, early in the war, Smith and his combat engineers were part of a 100-member force tasked with constructing a roadblock on the highway to Baghdad and to protect the eastern flank of the Saddam International Airport. PFC Richardson, all of 18, carried his platoon’s SAW squad automatic weapon.

Smith’s troops were erecting a pen to hold some Iraqi prisoners when someone spotted an enemy force of about 100 armed with AK-47s, rocket-propelled grenades and 60mm mortars.

Smith organized a hasty defense of two platoons, a Bradley Fighting Vehicle and three armored personnel carriers, according to official reports.

While shouting orders, Smith went to work himself. He lobbed grenades and fired on the Iraqis with his rifle and a bazooka to cover the evacuation of three wounded soldiers from a crippled troop carrier.

The Iraqis controlled a tower overlooking the compound. Smith knew he had to silence it.

“Under withering fire,” Smith raced across the courtyard and climbed onto one of the disabled carriers, which was armed with a .50-caliber machine gun. Smith tried to back the vehicle into the courtyard, but the attached trailer kept jackknifing.

Richardson and another soldier rushed out to unhitch it.

“Bullets were flying everywhere, pinging off the ground and walls,” he wrote to his parents after the battle.

Meanwhile, Smith climbed into the gun turret. With his upper body exposed, Smith blasted the tower with .50-caliber machine gun fire.

Smith had emptied three 100-round cans of ammunition when the gun suddenly went silent. Richardson and the others were just unhitching the trailer when he heard someone yell, “Sergeant Smith is hit!”

A bullet had pierced Smith’s skull. The ceramic breast plate in his flak jacket was shattered. Littering the ground were the bodies of more than four dozen Iraqis. One soldier later said the sight of Smith atop that troop carrier reminded him of “To Hell and Back.”

Paul Smith was the only U.S. casualty in the courtyard. He was 33 years old.

In the four-page letter from Dan afterward, Rita Richardson learned the harrowing tale of gunfire and confusion, and of the sergeant who held them all together.

“It is because of him that I’m not dead …” her son wrote. “He gave his life defending us.”

Dan Richardson’s mother has a decal on the trunk of her car: a red rectangle with a blue star in the center, signifying she has a soldier on active duty.

Paul Smith’s mother also has a peeling star, on her rear windshield. It is gold, the mark of someone who has given what Abraham Lincoln, creator of the Medal of Honor, called “the last full measure of devotion.”

Grief and gratitude will always link the families, Mrs. Richardson feels.

“Obviously, we will never forget what happened,” she said recently at her home in Sebastian on Florida’s east coast, where she and her husband retired in 2004. “Something put him in that place at that time in those circumstances.”

Letters and e-mails from the families of others who served with Smith still come to his mother and widow, thanking them for his sacrifice.

Some display his picture in a place of honor among their own family photos. Somewhere, there is a baby boy named Paul, in his memory.

Medic Michelle Chavez held Smith’s hand as he died under the hot Iraqi sun. In her pocket, she carries a .50-caliber machine gun bullet from the battle.

Because of Smith, she is alive to pursue her dream of becoming a physician’s assistant, says her mother, Pam Shorb.

“I really don’t know how to put it into words,” says Shorb. “I’ll always be grateful to him for what he did and what he sacrificed. Without our daughter, we don’t know what we’d be.”

Janice Pvirre says it hurts to know that because of those same actions, Paul was not there last October to give stepdaughter Jessica away in marriage. When 12-year-old David enters seventh grade this fall, it will be in a middle school building named for a father who is no longer there.

If anyone owes her anything, she says, it is to live as good a life as possible, so that Paul’s death was not in vain.

“I don’t feel that they need to thank me,” she says. “I mean, I had 33 wonderful years with this boy. I have been thanked enough. I’m blessed.”

Rita Richardson thinks her son is mindful of that duty.

In March, Dan got married. He is at Fort Benning, Ga., doing airborne training for a deployment to Italy.

His mother worries that he will be deployed again. She knows he will try to emulate Smith and that there is no use telling him not to be a hero.

On the parade ground at Fort Stewart, there is a path known as the Warriors Walk. Each time a soldier from the 3rd Infantry dies, a redbud tree is planted as a memorial.

When Dan’s unit returned from its first deployment, Mrs. Richardson says, there were just a few trees. Now, they line the grounds’ perimeter, two rows deep.

On the third anniversary of Paul’s death, his mother was on that same parade ground, sitting on the cold concrete bleachers as a brisk wind whipped the redbuds, whose purplish blossoms had given way to tiny green shoots. Members of the 3rd ID were coming home from another deployment, and she just wanted to be there.

Nearby, a little boy, no more than 5 or 6, sat squirming. “I can’t see my daddy,” he shouted. Suddenly, the boy spotted his father and burst onto the field.

“Nobody could catch him,” Pvirre says, grinning at the memory.

The boy threw himself at his father. The crowd laughed as the soldier marched along, the little boy clinging to his leg.

“It was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen,” Pvirre says, her eyes brimming with tears. “It did me a world of good to go out and see that.”

Though she had every right to be envious, she says she had a different feeling.

“I know that some of those kids came home because of my son,” she says, “and I’m very proud.”

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard