COURTESY OF THE TRIBUNE-REVIEW

Sunday, October 24, 2004

“Hotel Bemelmans,” by Ludwig Bemelmans, Overlook, $24.95, 302 pages.

Ludwig Bemelmans came to the United States in 1914, supposedly after he had shot and nearly killed a fellow employee of his uncle’s hotel in his native Austria, bearing two pistols (presumably one of them being that with which he did the dastardly deed) to fight off hostile Indians. That anecdote we perhaps can take to be among the first of scores of too-good-to-be-entirely-accurate stories associated with his writing career.

Bemelmans is best known for the series of perennially popular “Madeline” children’s books (begun in 1939, they were made into a movie as late as 1998) that he wrote and illustrated with watercolors of inspired amateurishness (similar drawings illustrate this volume). However, he wrote dozens of other books, most of them funny, among which were several dealing with his life as a hotel employee and from which the stories in this current collection are drawn.

If every story herein is not, as one suspects, literally and autobiographically true down to the last detail, that is not surprising. Anthony Bourdain, author of “Kitchen Confidential” — memoirs of his own career as a chef — says in his introduction to this work that he has heard versions of some of these tales so many times elsewhere that they have achieved the status of urban legends, such is the “seemingly endless continuity” of hotel and restaurant existence.

Besides, as Bourdain astutely notes, the “tone of the book is pitch perfect.” Bemelmans gives his own polish to nuggets of fact in the same way his New Yorker colleagues Joseph Mitchell, John McNulty and A.J. Liebling did.

In “I Was Born in a Hotel,” for example, is the lost world of Mitteleuropa before World War I such as cannot be found even in excellent histories like “The Proud Tower.” The writing is extremely vivid, yet controlled, especially when you consider it is done by a person for whom English is not the first language, as when he describes horses racing out of a brewery: “the skin of their haunches stretched into folds as they pushed the ground away from under them, sparks raining from under their hoofs as they struck the cobblestones.”

Bemelmans made a good living in the hotel business before turning to writing in the mid-1930s. He spent many years at New York’s Ritz-Carlton, masquerading here under the name Hotel Splendide.

Bourdain is generally correct when he remarks that the author “is decidedly nonjudgmental of his fellow workers, saving his wrath mostly for the clientele.” In “No Trouble at All” he describes an ostentatiously vulgar birthday party for an obscenely wealthy woman “whose skin had the texture of volcanic rock.”

“Mespoulet’s Promotion” is a cautionary and morality tale fit for our own day, for it shows how the rich get richer through not paying their fair share, and — talk about a sense of entitlement — fully expecting things to be that way.

And “Herr Otto Brauhaus” is a warm and loving portrait of a kind and decent man, the Splendide’s manager. It is a pity Otto’s curses cannot be printed in a family newspaper, even when filtered through his German accent, as they are very funny.

Yet even the employees occasionally get splashed with vinegar, if not acid. It is not exactly nice of “Monsieur Victor of the Splendide,” the chief headwaiter, to treat guests who are nobodies in a humiliating way. Nor, in “The Animal Waiter,” for him to use “as kind of penal colony” the remoter tables where Bemelmans and his partner are stationed. “Rarely did any guest who was seated at one of our tables leave the hotel with a desire to come back again.”

The president of the company, based in London, that owns the Splendide embodies his own personal kind of awfulness. Whenever he visited the Splendide, he always brought with him his niece. “He had many nieces, the chambermaid told me; this was the fifth one, and always a different one came with him from England.”

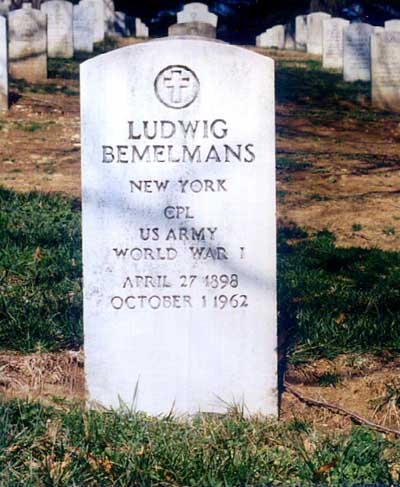

Bemelmans and the grand hotels of his time are long gone. He died in 1962 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery (he served in the U.S. Army in World War I, an experience related amusingly in his book, “My War With the United States”).

So there is no reason to read this book except for the sheer joy of it. It is a book for all time about a particular time, one when things were not necessarily more innocent — they never were — but less complicated, and “the niceness of people could be seen.”

April 27, 1898-October 1, 1962

BEMELMANS, LUDWIG (April 27, 1898-October 1, 1962), Austro-American essayist, humorist, novelist, artist, and author of books for children, was born in Meran, in the Tyrol, in territory that was then Austrian and is now Italian. When he was eight his parents divorced (his father had been a painter of somewhat irregular habits) and his mother took him to live with her family in Regensburg, Germany. A rebellious child, he was enrolled in various schools and private academies and failed at most of them. Not knowing what else to do with him, his family apprenticed him in 1912 to an uncle who owned a number of hotels in the Tyrol. For the next two years he worked at, and was dismissed from, most of these establishments. After supposedly shooting and almost killing a waiter he was given a choice: reform school or emigration to America. He chose the latter and in 1914 arrived in New York with letters of introduction to managers of several large hotels.

Having worked his way up to a position as a waiter at the Ritz-Carlton, he left to enlist in the United States Army in 1917. Bemelmans worked at home with German-speaking recruits and as a guard in military hospitals (an experience recounted in My War with the United States), became naturalized in 1918, and returned to the hotel and restaurant business in New York the following year. Eventually he opened his own restaurant; only in 1934 did he turn to writing, at the suggestion of a friend in publishing who, noticing the whimsical paintings with which he covered the walls of his apartment, urged him to undertake a children’s book.

Hansi, the first of Bemelmans’ fifteen books for children, beguiled most reviewers with its simple watercolor illustrations and nostalgic story of two children and their dog in the Austrian Tyrol. His greatest success, however, was Madeline, a rhymed picture book about a Parisian schoolgirl who becomes the envy of her classmates when her appendix is removed. Indeed, the Madeline books, of which there were five, remain the work that Bemelmans is primarily remembered for. The inspired amateurishness of the illustrations and the sophisticated doggerel verses have been an influence on later juvenile literature. Madeline’s Rescue, the second book in the series, was awarded the Caldecott Medal in 1953.

Bemelmans’s first book for adults, My War with the United States, was actually his translation of the diary he had kept during his World War I service. As most of his books did, it struck critics as fresh, witty, and irreverent, although it was not without intimations of cruelty and madness (notably in the scenes touching on the horrors of military hospitals). “Bemelmans writes of his extraordinary adventures with a child’s eye, a lyric detachment and a certain naive curiosity that appropriately accompanies his personal story,” wrote a reviewer in the New York Herald Tribune. “His book is unconventional but wiser than his light mood suggests at first sight.”

Bemelmans claimed to have no imagination, and all his books were the more or less direct product of his experience. He enscribed his life as a restaurateur in Life Class and Hotel Splendide, his travels to Ecuador and Italy in The Donkey Inside and Italian Holiday, and his stint as a Hollywood screenwriter in the novel Dirty Eddie. At the time of his death he was working on the story of his childhood. Bemelmans was a genial satirist and lover of life, but a serious intent often underlay his humor, especially in his novels. A case in point is Blue Danube, a fanciful story set on an island of the Danube, the comedy of which is very much clouded by the appearance of a band of odious Nazis. Blue Danube was not Bemelmans at his best — “the sentimental Bemelmans,” wrote A. J. Liebling in the New Yorker, “is in the ascendant again”–but it did demonstrate his awareness of the proximity of comedy and tragedy. A somewhat more successful novel was Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep, concerning the unusual journey of an elderly Ecuadoran general from his villa in Biarritz to his home in South America. It too had a point to make, but did so with a more characteristic deftness. It was, wrote another New Yorker critic, “a satire which manages to be not only brashly funny but a subtle statement about human behavior in its more futile aspects.”

From the time of his marriage to Madeline Freund in 1935 (they had one daughter, Barbara) until his death in New York of pancreatic cancer, Bemelmans traveled, painted, dined in the elegant restaurants that he loved, and generally wrote a book or two a year. He was a contributor to Town and Country, Horizon, and the New Yorker, for the last of which he did many cover illustrations. In later years Bemelmans considered himself a painter first and a writer second, and his work was shown in several New York galleries. Reviewing his posthumous novel, the comic love story The Street Where the Heart Lies, Burling Lowrey in Saturday Review called Bemelmans “a superb craftsman with a sure eye for atmospheric detail and a supremely accurate ear for the speech of Adult Innocents madly in love with the unattainable.. . .He was a complete original, with an absolutely unique temperament and view toward the world.”

Selected Works: General nonfiction–My War with the United States, 1937; Life Class 1938; Small Beer, 1939; Hotel Splendide, 1941; I Love You, I Love You, I Love You, 1942; Hotel Bemelmans, 1946; My Life in Art, 1958. Travel–The Donkey Inside, 1941; The Best of Times: An Account of Europe Revisited, 1948; How to Travel Incognito, 1952; Italian Holiday, 1961; On Board Noah’s Ark, 1962. Novels–Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep, 1943; The Blue Danube, 1945; Dirty Eddie, 1947; The Eye of God, 1949; The Woman of My Life, 1957; Are You Hungry, Are You Cold, 1960; The Street Where the Heart Lies, 1963. Biography–To the One I Love the Best, 1955. Juvenile–Hansi, 1934; The Golden Basket, 1936; The Castle Number Nine, 1937; Quito Express, 1938; Madeline, 1939; Fifi, 1940; Rosebud, 1942; Sunshine: A Story about the City of New York, 1950; The Happy Place, 1952; Madeline’s Rescue, 1953; The High World, 1954; Parsley, 1955; Madeline and the Bad Hat, 1956; Madeline and the Gypsies, 1959; Madeline in London, 1961.

Bemelmans is buried in Arlington National Cemetery (Section 43, Grave 2618).

BEMELMANS, LUDWIG

- United States Army

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: 08/02/1917 – 11/29/1918

- DATE OF BIRTH: 04/27/1898

- DATE OF DEATH: 10/01/1962

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 10/04/1962

- BURIED AT: SECTION 43 SITE 2618

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard