Story and Photos Courtesy of the United States Marine Corps

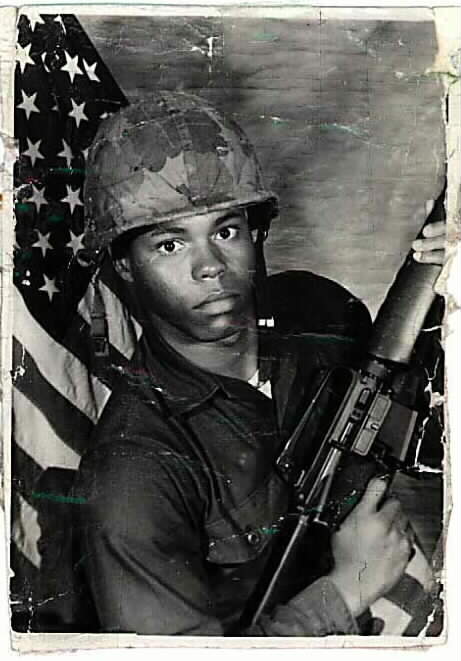

NORFOLK, Va. (June 9, 2000) — The tattered edges of the photograph are worn with love. So many times, Marian Boyd, 62, pulled the picture from her wallet just to get a glimpse of her son.

Walter “Butch” Boyd joined the Marine Corps in 1975.

“Mama, I’m going to make someone proud of me,” he told his mother as he shipped out to Camp Pendleton, Calif. to join the 2nd Battalion, 9th Marines.

Not long after he arrived in California, his unit was part of a rescue attempt of the crew of an American merchant ship in Cambodia.

The helicopter that carried him and 25 other Marines was hit by an enemy rocket and sent to the bottom Gulf of Thailand

“If he were here today,” David Boyd, his brother, said, “I’d tell him how very proud I am of what he did ? what he had become.”

Walter Boyd set the example for his five younger siblings when he dedicated himself to getting out of his Tidewater Park public housing neighborhood and making something of his life.

“It’s easy in the projects to take a wrong turn in life,” said Boyd, 39. “My brother wasn’t going to let that happen to him.”

After dropping out of Booker T. Washington High School in 10th grade, Walter Boyd joined the Job Corps before enlisting in the Marines in 1975.

“The Marines had a positive influence on his life,” said Boyd of his brother. “They changed him ? made him much more mature. He was very proud to be a Marine.”

For David’s part, he looked up to his brother even more.

That was a tall order for a 15-year-old boy who looked up to his older brother as his male role model.

On May 12, 1975, world events had a devastating impact on the Boyd family in Norfolk.

Khmer Rouge gunboats captured the SS Mayaguez in the Gulf of Thailand, 60 nautical miles off the coast of Cambodia. The vessel was taken to Koh [island] Tang.

After efforts to secure the release of the ship and its crew failed, U.S. military forces were ordered by President Gerald Ford to undertake a rescue mission.

Six Air Force helicopters were dispatched to the island. One of the helicopters ? the one carrying Pfc. Walter Boyd ? came under heavy enemy fire as it approached the eastern beach of the island. The aircraft crashed into the surf with 26 men on board. Half were rescued at sea, leaving 13 unaccounted-for.

In October and November 1995, U.S. and Cambodian specialists conducted an underwater recovery of the helicopter crash site where they located numerous remains, personal effects and aircraft debris associated with the loss.

Marian Boyd was contacted by the U.S. Army Central Identification Laboratory Hawaii, which asked her to give a DNA sample to determine if her son was among those recovered.

In all, six Marines were accounted for. One of them was the 19-year-old man who set out to make someone proud in 1975. He did.

David recalls fondly the memories of his older brother teaching him how to throw a football, to roller skate, to hold his breath under water. But more importantly, the elder Boyd kept his brother on “the right path.”

“If he saw me hanging out on the corner with the fellas, he’d run me off. He’d always tell me I was throwing my life away hanging around on that corner. He was right.”

After his brother’s helicopter went down, David Boyd spent a lot more time on that corner.

Without his brother steering him down the “right path,” he experimented increasingly with drugs ? alcohol, marijuana, LSD, cocaine, heroine.

“When I first heard the news of my brother, I was very angry,” he said. “I had an I don’t care attitude.

“When my brother died, part of me died, too. I fell deeper and deeper into the drug scene and the street scene.

“I couldn’t understand why lives were being wasted that way during the war ? why my brother’s life was wasted.”

Fourteen years after his brother was reported missing in action, David Boyd was still angry, and his drug and alcohol use continued.

“I was doing just what my brother had always kept me from doing ? throwing my life away,” Boyd said. “I knew I had to get it together.”

In 1989, David Boyd said he gave his life to the Lord.

“It was the best thing that ever happened to me,” Boyd said. “Not only did it help me turn my life around, it helped me come to grips with what happened to my brother.

“It’s a question of maturity. When I was 15, I didn’t understand what it meant to make the sort of commitment that my brother made.

“Over the years, I have come to realize that when a person signs up for military duty, risk is part of it. At the time, I couldn’t see it, but over the years, I’ve had a lot of time to think about it. He knew the risk he was taking ? he knew what he was doing, and he was man enough to live up to the choices he made.”

Boyd said that now he realizes that his brother and all of those who served in the military “made the way for me and my family and all of the things we enjoy.”

It took him a while. In the first 14 years after his brother?s death, he said, “I wasn’t fit to have a family.

“With all of the drugs and alcohol, I would have made a poor husband and a worse father.”

That’s all behind him now, he said. These days, Boyd drives a local delivery route for a tire company. He is married to Bonita Boyd. They have three children ? Brittani, 8; David Jr., 6; and Davon, 5.

“If he knew how I was raising my children, Butch would be real proud of me,” Boyd said. “He’d know I was showing them the right path.”

Boyd said he often thinks about what might have been ? what his brother might have become. What he, himself, might have accomplished if he got those 14 wasted years back.

Still, Boyd said the family has learned not to dwell on painful memories.

Like that tattered picture in Marian Boyd’s wallet, the family has long since learned to look past the rough edges surrounding the tragedy in Southeast Asia and to see what is most important ? their happy memories with Walter.

When the Boyds got word that the government had positively matched the remains of Walter, those memories came swirling in all around them.

“It drew us closer together than ever,” David Boyd said. “This was a devastating blow to our family, but it has also served to make us stronger.”

Even Walter’s father, who left when Walter was only 6, is back in the picture. He lives in New York now and made the trip to Arlington National Cemetery June 9 for a memorial service for his son. He had missed the first ceremony when a marker was placed in the Hampton National Cemetery in his son’s honor.

“I often think about things and try to understand why they happen the way they do,” David Boyd said. “I think I know why this ? all of this ? has happened. When we were kids, Walter was always the one to hold the family together. He was our leader.”

In some ways, he still is.

“In our family, he is truly a hero, and it is entirely fitting that he be buried in a place that he is surrounded by heroes.

“If I could talk to him today, I’d tell him how very proud I am of him ? that he made the ultimate sacrifice for what he believed in. He is truly a hero.”

But, more important, Boyd said, is that he was a good man ? a man who his little brother still strives to be like.

“The thoughts that go through a person’s mind when your name is mentioned is who you are,” he said.

“When someone mentions my brother’s name, good thoughts come to mind.”

With the accounting of these six Marines, 2,022 Americans remain missing in action from the Vietnam War. Another 561 have been identified and returned to their families since the end of the war.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard