From a contemporary press report:

Clark Clifford, the silver-haired Brahmin of the nation’s political establishment who advised presidents across half a century of American history, died Saturday (October 10, 1998) morning at the age of 91 at his home in Bethesda, Maryland.

A secretary of defense for one president, friend and confidant of three others, Clifford frequently played the role of capital wise man in inner-sanctum crises, helping President Harry S. Truman find peace with labor and warning President Lyndon B. Johnson about the folly of the Vietnam war.

With a gentle drawl and an insider’s run of the halls of power, Clifford was consulted as well by Presidents John F. Kennedy and Jimmy Carter, bridging the nation’s postwar political era until he ran into legal troubles in high-finance brokering.

For all the roles he played in presidential history, Clifford faced a rigorous ordeal in his final years, insisting on his innocence to the end as he faced charges of fraud, conspiracy and taking bribes in the biggest banking scandal in history, the collapse of the Bank of Credit and Commerce International.

It was only earlier this year that Clifford and his law partner, Robert A. Altman, reached a $5 million settlement with the Federal Reserve Board, after federal prosecutors had whittled down the case against them. Altman had been acquitted in 1993 in New York state court of charges of bank fraud; indictments against Clifford had been set aside because of his failing health.

Clifford considered his role in extricating the United States from what he called that “wretched conflict in Vietnam” to be his finest moment; the day he was indicted and fingerprinted like a common criminal, he said, was “the worst.”

Few people in Washington, let alone Clark Clifford himself, could have imagined so inglorious an end to so glorious a career. From the time in World War II when he went to Washington as a naval aide to Truman, Clifford was a highly respected lawyer and public servant about whom scarcely an unkind word was ever uttered.

He was a symbol of elegance — 6 feet 2 inches tall, trim, wavy-haired, his french cuffs always a 1/2-inch longer than the sleeves of his impeccably tailored double-breasted suits.

There were a few who saw in him a little too much smoothness, a touch of the riverboat gambler, perhaps. But to most people who knew Clifford, he was a symbol of probity, even a legend in his own time. Except for Spiro Agnew and a lone article in Ramparts magazine, nobody had a bad word to say about him in public, at least not until the BCCI scandal.

Counsel Given to Four Presidents

Whether in the White House or in his law offices across the street from the White House, Clifford was the man politicians and business leaders turned to for advice. Johnson, beleaguered by the Vietnam War, turned to him to be his secretary of defense, and Carter called on him to be a White House adviser. Kennedy asked him for legal help and put him at the head of his transition team, and Truman appointed him special counsel.

Few people in government were as familiar with as many of the nation’s problems as Clark Clifford. He helped articulate the policies for the reconstruction of Europe after World War II. He wrote the basic legislation establishing the CIA and the Defense Department. On the domestic front, he wrote some of Truman’s most important speeches and helped keep labor peace in the postwar period.

With a thriving private law practice, Clifford liked to think of himself as a bridge between business and government. But he was more than that. Like many lawyers who made up the Washington establishment, he advised corporations on how to navigate their way through laws and regulations.

For each new client he had the same well-rehearsed speech that he offered to one of his first clients, Howard Hughes. As Clifford recounted it in his memoir, “Counsel to the President” (Random House, 1991), he said his firm had no influence and would not represent anyone before the president or any of his staff.

“If you want influence you should consider going elsewhere,” he would tell prospective clients. “What we can offer you is an extensive knowledge of how to deal with the government on your problems. We will be able to give you advice on how best to present your position to the appropriate departments and agencies of the government.”

He gave the same speech to the Arab investors who came to see him in 1978, the same investors who, it turned out, were front men for the Bank of Credit and Commerce International. The bank, which was chartered in Luxembourg and the Cayman Islands and had offices in 70 countries, was shut down in July 1991 in a worldwide swoop by banking regulators.

BCCI was accused of fraud, laundering drug money and bribing bank regulators and central bankers in 10 developing countries. It was reported to have $20 billion in assets shortly before the shutdown, but liquidators have been unable to find many of its assets.

The Importance of Credibility

In an interview in the mid-1980s, Clifford said his concept of the practice of law “is that through the years you conduct yourself in such a manner that the staffs of the government agencies have confidence in your integrity and your credibility.” He added, “I’ve never contended that I have influence, felt I had influence or attempted to use influence.”

It was precisely his reputation for integrity and credibility that led the group of Arab investors to seek Clifford’s help in the late 1970s when they wanted to acquire an American bank. The Federal Reserve Board approved the takeover in 1981, reassured by Clifford that there would be no control by BCCI, which he also represented.

The fact that Clifford himself was to become chairman of the new bank provided further reassurance to the regulators. The bank, with Clifford as its chairman, was called First American Bankshares and became the largest in Washington.

Ten years later, Robert Morgenthau, the district attorney in New York City, disclosed that his office had found evidence that the parent company of Clifford’s bank was secretly controlled by BCCI. The district attorney convened a grand jury to determine whether Clifford and his partner, Altman, had deliberately misled federal regulators when the two men assured them that BCCI would have no control.

Clifford’s predicament worsened when it was disclosed that he had made about $6 million in profits from bank stock that he bought with an unsecured loan from BCCI. A New York grand jury handed up indictments, as did the Justice Department. Clifford’s assets in New York, where he kept most of his investments, were frozen.

Clifford said the investigation caused him pain and anger. If the regulators had been deceived about any secret ownership by BCCI, he said, he too had been deceived.

But if he was deceived, it would have been an aberration. While Washington lawyers like Clifford say they do not “sell” influence, what they do offer is sophistication, experience and knowledge of the mechanics of government. That is why it was so difficult for people to believe that Clifford, who was so experienced at seeing around corners and anticipating problems for his clients, could have been duped by front men for BCCI.

“It’s easy to say I should have known, but a client tells his lawyer what the client wants the lawyer to know,” Clifford said. “I have to admit that they came to me because of my standing and reputation. If you think of that, then you’d understand better that I’d be the last person they’d divulge this stuff to. I gave them standing. Why would they jeopardize that? They knew if they told me, I’d be out the door.”

A ‘Wretched’ War: Pride and Regrets

Although he spent a total of only six years in government service, those were the years that he liked to dwell upon. Looking back one day in the mid-1980s as he was preparing to publish his memoirs, he said in his customary measured tones, “I believe the contribution I made to reversing our policy in that wretched conflict in Vietnam is very likely the most gratifying experience I have had.”

There was no sense of self-congratulation. “I was part of the generation that I hold responsible for our country’s getting into that war,” he said. “I should have reached the conclusion earlier that our participation in that war was a dead end.”

Clifford added: “I’ve been quite severe with myself that I didn’t make a greater issue of it with President Johnson. I permitted myself to be lulled into a false sense of optimism over reports that came back from Vietnam.”

But in the nine months that he headed the Defense Department, succeeding Robert McNamara in 1968, Clifford used everything he had ever learned about the levers of power, all his skill as an advocate and all his political capital to persuade the president not to further escalate the role of American ground troops in South Vietnam. U.S. military involvement in Southeast Asia, Clifford argued, was sapping the nation’s strength as a world power.

In his later years, no longer in government service, he sought to end the arms race as he had once tried to end U.S. participation in the Vietnam War. When he began in government, the world had two atomic bombs. Within four decades the world had 24,000 nuclear bombs, and that awesome fact continued to preoccupy him long after he left public office.

In the Truman years, Clifford wrote that the language of military power was the only language the Soviet Union understood. He was nevertheless a consistent advocate of finding a way to coexist with the Russians, and urged the adoption of arms agreements and a nuclear freeze. He often said he was haunted by a remark Winston Churchill had made about the superpowers and the arms race: “All they’re going to do is make the rubble bounce.”

Old World Grace, Midwestern Openness

Trim and disciplined — he kept his weight at 180 pounds and allowed himself dessert only when he fell below that, and he smoked one cigarette a day, proving to doubters that he could do it — Clifford was the personification of Old World grace combined with a kind of Midwestern openness.

To close the door on entering Clifford’s office meant to close out the hurried pace of the 20th century and to return to the more measured rhythm of the 19th. In the cauldron of the Vietnam-era Pentagon or in the paneled luxury of his Connecticut Avenue office, there was always time for the niceties of gentlemanly conversation. He would inquire after one’s spouse, and ask whether the children were writing from college.

The quintessential insider, Clifford had access to the corridors of power and to the private clubs that were the marks of success. He tried to play golf at Burning Tree Country Club in Maryland every weekend, but he liked to take his lunch at the People’s Drugstore around the corner from his office. He said he could have a sandwich and a glass of skim milk in 22 minutes at the lunch counter there, while his occasional visits to the Metropolitan Club meant an hour and 22 minutes.

His office kept a car and chauffeur at his disposal, but until his health declined, he liked to drive himself to work from his 150-year-old house on Rockville Pike in Bethesda, Md.

No one can recall a time when Clifford raised his voice. What Washington veterans do remember was his ability, even into his 80s, to speak, seemingly extemporaneously and without notes, for 40 minutes. In fact, Clifford prepared every statement carefully and then memorized it. “The mind is a muscle,” he said. “The more I use it, the better it gets.”

Clifford had a way of taking his listeners step by step through an argument, pausing every now and then to ask rhetorically, “Do you see?” as he ushered them along with careful logic.

“Clark was so smooth that when you lost with him, you thought you’d won,” said Phil Goulding, an assistant secretary of defense under Clifford.

His Father’s Words: ‘To Live Is to Work’

Clark McAdams Clifford was born in Fort Scott, Kansas, on December 25, 1906. He was named for his mother’s brother, Clark McAdams, a crusading editor of The St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

His mother, Georgia McAdams Clifford, was, as her son remembered her, a great storyteller, very dramatic and “beautiful beyond belief.” His father was an official of the Missouri Pacific Railroad, a man who, Clifford said, “instilled in me the precept that to live is to work.”

“He developed in me habits of industry — too much, my wife thinks sometimes,” Clifford said.

He was given chores to do when he was a boy, and as he got older the tasks increased. When the family moved to St. Louis, he was a delivery boy for a grocery store and in the summertime was a night delivery boy for a drugstore. He also remembered earning $30 a month for singing in a choir.

“I had an extremely happy childhood — it was ideal,” Clifford said. “I thought everybody loved his mother and father and would go to the wall for his sister. Boy, was I naive!”

Clifford attended college and law school at Washington University in St. Louis. On graduating in 1928 he entered law practice there. In the summer of 1929, while traveling in Europe, he met a Boston woman, Margery Pepperell Kimball. They were married on Oct. 3, 1931.

In addition to his wife, he is survived by their three daughters, Faith Christian, of Chico, Calif., Joyce Burland, of Halifax, Vt., and Randall Wight, of Baltimore; 12 grandchildren and 17 great-grandchildren.

From Naval Aide to Truman Adviser

Although Clifford was over the draft age and was already a father when the United States entered World War II, he volunteered for the Navy in 1943 and was accepted as a lieutenant junior grade. After an assignment to assess the state of readiness at naval bases on the West Coast, he was drawn into the White House in 1944, where he began a career, as the columnist James Reston once put it, of rescuing American presidents from disaster.

In July 1945, when Truman attended the Potsdam Conference near Berlin, Clifford found he did not have enough to do. “You’re kind of a potted plant when you’re a naval aide,” he recalled. “So I offered to be helpful to Judge Samuel I. Rosenman, the special counsel, who had more work than he could handle.” When the president returned, Rosenman said, “Let’s keep that young fellow here.”

As a speechwriter, and later as special counsel to Truman, Clifford helped articulate the Truman Doctrine, a program proposed in 1947 to help Greece and Turkey resist potential communist expansionism, and related innovative programs for assisting underdeveloped countries.

Clifford also participated in the creation of the Marshall Plan for the rehabilitation of Western Europe and in the formation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

It fell to Clifford to be Secretary of State George Marshall’s adversary on the issue of recognition of Israel. “President Truman said he would like me to prepare the case for the formation of a Jewish homeland as if it were a case to be presented to the Supreme Court,” Clifford said.

Marshall, who opposed recognition, became almost apoplectic at a White House meeting when Clifford made his points — points that he could still reel off in detail 40 years later. When Truman decided in favor of immediate recognition of Israel, Clifford said, there were some tense days until Marshall relented.

Clifford insisted that Truman acted out of conviction and humanitarian considerations, not for domestic political advantage as Marshall had suggested.

Kitchen Cabinet and Poker Games

In his years in the Truman White House, Clifford was a poker-playing regular of the kitchen cabinet; he even played a hand or two with Churchill.

Clifford was an important architect of the president’s “give ’em hell Harry” whistle-stop campaign in 1948, when Truman won an upset victory over the Republican nominee, Thomas E. Dewey.

Clifford was also one of the principal architects of the National Security Act of 1947, which unified the armed services and established the CIA. Amendments that he framed two years later greatly strengthened the authority of the secretary of defense.

In his memoirs, he expressed regret that he had not made a greater effort to kill the loyalty program instituted to root out communist subversives. But he has been criticized for contributing to the climate of fear by the proposition that “the United States must be prepared to wage atomic and biological warfare if necessary.”

Clifford left the White House in 1950 to open a law firm in Washington, hoping to repair his personal finances, which had been tattered by his years in the government, most of them at an annual salary of $12,000.

When Truman discussed with him the possibility of a seat on the Supreme Court, Clifford said he would not be happy there. In 1949 he turned down an offer from a group of prominent Missouri Democrats to run for the Senate.

“I’d been in the Navy and the White House for almost seven years,” he said, looking back at that period. “I had three growing daughters reaching the age when daughters become expensive, and going through this economic ordeal again that I’d been through was an obstructing factor I could not overcome at that time.”

Making Millions as a Superlawyer

After leaving the government, Clifford overcame his economic problems so quickly that within four months he was able to move his family from a rented house in Chevy Chase, Md., to the historic house on three acres outside Bethesda that was his home for the rest of his life.

Clients lined up outside his door. One of the first was Hughes, who asked Clifford to be the Washington counsel for Trans World Airlines. There followed a clientele that represented blue-chip America and included General Electric, AT&T, ITT, RCA Corp., ABC, DuPont, Hughes Tool, Time Inc., Standard Oil, Phillips Petroleum and El Paso Natural Gas.

In time, the man whose early ambition was to be the finest trial lawyer in St. Louis became the first Washington lawyer to make a million dollars a year — because it was thought that he could fix things for his clients as a result of his political connections. Clifford said he always found this concept deeply disturbing.

But the legend of his influence had grown so that a favorite story around Washington was that whenever Clifford had occasion to go to a government office on behalf of a client, the meeting would be interrupted by the announcement that the president was calling Clifford.

“That happened exactly once,” he protested. The president, he said, was Kennedy, and there was a genuine emergency at the White House.

In the Eisenhower years Clifford was not called by the White House, but he remained active in Democratic politics. He was also the personal lawyer for Kennedy, then a young senator from Massachusetts.

In 1960, when Kennedy won the Democratic nomination for president over Stuart Symington, whom Clifford had supported, Kennedy asked Clifford to prepare an analysis of the problems Kennedy would face in taking over the executive branch. Clifford wrote a detailed assessment and, after the election, was named to head the transition team.

At a dinner shortly after his election, Kennedy paid tribute to Clifford for all the work he had done and for asking nothing in return. “All he asked was that we advertise his law firm on the back of one-dollar bills,” the president-elect quipped.

After the abortive invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs in April 1961, an operation supported by the CIA, Kennedy again turned to Clifford, who in 1947 wrote the legislation establishing the agency. The president asked him to become a member, and then chairman, of the newly created Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board.

Kennedy also turned to Clifford a year later, when the nation’s major steel companies refused to honor an agreement that the president thought he had with them not to increase prices. The companies backed down several days later, after Clifford convinced them that it would be in their best interest to rescind the increases.

Johnson was hardly in office 24 hours when he called for Clifford. Faced with the sudden and enormous task of running the country after Kennedy’s assassination, Johnson talked with Clifford for two hours, then three, then four. It was late in the evening, Clifford remembered, when Lady Bird Johnson entered the Oval Office and reminded her husband, “Just because you’re president now doesn’t mean you don’t have to eat dinner.”

Rift Over Vietnam Strains a Friendship

Clifford’s warm relationship with Johnson became strained and almost broke over Vietnam in 1967, when Johnson asked him to be secretary of defense. Clifford’s first assignment was to determine how to meet Gen. William Westmoreland’s request for 206,000 more U.S. troops in Vietnam. The special panel Clifford set up to study the issue soon became a forum for debating the rationale for the war.

Because he then had the complete confidence of the president, whom he had known for more than 20 years, and because he had the luxury of not being bound to previous official positions on Vietnam, Clifford was able to ask the difficult questions. He did not like the answers. No one could say whether the 206,000 troops would be enough. No one could say whether the war would take another six months, a year, two years or more.

Clifford finally came to the conclusion that there was no plan for military victory in Vietnam and that the United States was in what he called “a kind of bottomless pit.” He said he realized that “we could be there year after year, sacrificing tens of thousands of American boys a year, and it just didn’t add up.”

When Clifford began to oppose Johnson on the war, a rift opened. Clifford remembered a “sense of personal hurt that I was doing this to him.” To help heal the breach, Clifford asked Johnson to have lunch at his home on his final day in Washington, the day Nixon was inaugurated as president. Johnson accepted and, as one of his last official acts, awarded Clifford the Medal of Freedom with Distinction, the highest award given to civilians in the United States.

Having persuaded Johnson to cut back the bombing and negotiate an end to the war, Clifford spent the next years trying to urge Nixon to end the war. His efforts led Vice President Spiro Agnew to accuse him of being “a late-blooming opportunist who clambered aboard the rolling bandwagon of the doves when the flak really started to fly.”

Except for Agnew’s comments and a broadside from Ramparts magazine at the other side of the political spectrum, Clifford’s more than 40 years in Washington passed with a relative absence of criticism, until the bank scandal broke.

At the time, no one paid much attention when Ramparts called Clifford a “curious hybrid of Rasputin, Perry Como and Mr. Fix,” in an article that depicted him as an architect of U.S. States economic imperialism and linked that role to his legal work representing major multinational corporations.

Only once in his long career did he step out of character, and that was when he referred to President Ronald Reagan as an “amiable dunce.” The remark was made at a private dinner party but, unknown to Clifford, a tape recording had been made so that the hostess, who was ill with the flu and unable to come to her own party, could hear what was expected to be some sparkling conversation. Excerpts from that tape were published out of context.

Clifford explained his remark this way: “In the fall of 1982, President Reagan said he would cut taxes by $750 billion, substantially increase defense expenditures and balance the budget in the 1984 fiscal year. Those were public promises. I made a comment that if he would accomplish that feat, he’d be a national hero. If, on the other hand, it did not work out after such a specific and encouraging promise and commitment, I thought the American people would regard him as an amiable dunce.”

Given the opportunity some time later to retract his remark, however, Clifford declined to do so.

In time, even Carter, who kept his distance from the Washington establishment, turned to Clifford for advice — when Carter’s budget director, Bert Lance, came under attack for his banking practices in Georgia. A former Kennedy aide later remarked, “They ran against Washington, but when the water comes up to their knees, they call for Clark Clifford.”

A New Challenge in His Later Years

It was Lance who introduced Clifford to the Arab investors who sought to take over the bank in Washington that was to become known as First American Bank. Clifford and his young partner, Altman, structured the deal that led to the takeover of the bank and, according to prosecutors, the success of the Bank of Credit and Commerce International in the United States. Clifford said to the end that he did not know that BCCI had been behind the purchase of the bank.

For him, the bank became a new challenge for his later years. He looked at his contemporaries who had retired, and did not like what he saw, he said in an interview in The Washington Post.

“Some of them would go with their wives each morning to the market and help with the marketing, pushing those carts and all,” he told the interviewer. “Well, I didn’t find that very appealing.”

Secondary press report:

Saturday, October 10, 1998) — Clark M. Clifford, the consummate Washington insider and a top adviser to four Democratic presidents, died early this morning. Clifford, who was 91, had been in ill health in recent years — a period that saw his once distinguished reputation tarnished by an international banking scandal. No one in Washington, no one in the country, operated so close to power for so long. Clifford, defense secretary in the Johnson administration, was a powerful attorney and an adviser who whispered into the ears of Harry S. Truman, Lyndon Johnson, John F. Kennedy and Jimmy Carter. They were long gone from the scene when Clifford became embroiled in a scandal that dragged his name into headlines again from mid-1991 until late 1993 in the BCCI banking case. Criminal charges were dropped in 1993 because of his age and ill health, and the last of several civil suits prompted by the case were settled last month. His health had been deteriorating for some time, and he died at 2 a.m. today, his daughter, Randal Wight, said. Clark McAdams Clifford, born in Fort Scott, Kan., on Christmas Day 1906, got his law degree from Washington University in St. Louis and practiced law there for 15 years. In World War II, he joined the Navy, then came to Washington as assistant to Truman’s naval aide, a St. Louis friend. One of his jobs was to help unescorted women to their seats at ceremonial occasions; another was redesigning the presidential seal. It wasn’t long, however, before he headed for bigger things. A Clifford memo, which reached Truman, argued that ”the Democratic Party is an unhappy alliance of Southern conservatives, Western progressives and Big City labor.” Clifford said Democratic success depended on the ”ability to lead enough members of these three misfit groups to the polls.” Clifford’s idea was that Truman be ”controversial as hell” in the 1948 campaign. Clifford has been credited with inventing Truman’s innovative whistle-stop campaign in which he rallied farmers to his side, but in truth no one knows whose inspiration it was. The Washington lawyer was summoned back to the White House by President Kennedy after the 1961 Bay of Pigs debacle in Cuba. He suggested that the president create an independent presidential board to oversee the intelligence community, which stood accused of misleading Kennedy. In his memoirs, ”Counsel to the President,” Clifford says he rejected Truman’s suggestion that he take a seat on the Supreme Court and that Johnson offered him the posts of ambassador to the United Nations, national security adviser, CIA director and undersecretary of state, all of which he turned down. But he said he could not refuse the Defense Department job since he had drafted the legislation that created the Pentagon. Carter came to the White House deeply suspicious of Washington insiders like Clifford. But he, too, used Clifford, to help win Senate ratification of the Panama Canal treaties. Clifford was director emeritus of Knight-Ridder newspapers. He was a recipient of the presidential Medal of Freedom. But the public life of the patrician, white-haired epitome of respect was not over. Clifford and his former law partner, Robert Altman, were indicted in July 1992 on charges of fraud and accepting $40 million in bribes from the foreign-owned Bank of Credit and Commerce International. Both were charged with concealing from federal regulators BCCI’s secret ownership of First American Bankshares Inc., the big bank holding company in Washington they had headed since 1982. The two also had been attorneys for BCCI. They denied the separate federal and New York state charges against them and said they were duped by BCCI’s Pakistani executives. Clifford and Altman abruptly resigned from First American in August 1991, a month after BCCI itself was indicted amid allegations of massive fraud, laundering of drug money and supporting terrorists. BCCI pleaded guilty in January 1992 to federal racketeering charges and agreed to forfeit a record $550 million in U.S. assets. Altman, 40 years Clifford’s junior, stood trial in New York from March to September 1993 and was acquitted of all state charges. Clifford’s trial was delayed indefinitely so he could recuperate from quadruple heart bypass surgery, but he considered Altman’s acquittal to be his own vindication. Clifford leaves his wife, the former Margery (Marny) Pepperell, their three daughters, 12 grandchildren and 15 great grandchildren.

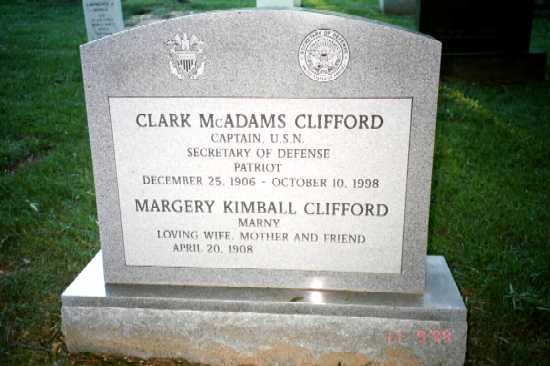

He was buried in Section 7-A, Arlington National Cemetery.

Margery “Marny” Kimball Clifford, 91, a cookbook author and interior decorator who was the widow of former Defense secretary and presidential adviser Clark M. Clifford, died of heart ailments April 14, 2000 at home in Bethesda, Maryland.

Mrs. Clifford settled in the Washington area after World War II when her husband, then a Navy officer, became an adviser to President Harry S. Truman. She came here from her native St. Louis, where she had founded and become the first president of the St. Louis Opera Guild. She also studied painting in St. Louis.

In the Washington area, Mrs. Clifford was known as an accomplished hostess and a superlative cook. She was a graduate of the Fannie Farmer School of Cooking in Boston and the author in 1972 of her own cookbook, “Marny Clifford’s Washington Cookbook.” In 1985 she published another cookbook, “A Harvest of Fine Recipes,” which was collected from friends, New England forebears and from her foreign travels.

At the age of 6, she moved from St. Louis with her parents to Philadelphia and later to Boston, where she studied piano at the New England Conservatory. She also attended secretarial school, promoted a new line of cosmetics and did some interior decorating, including the New York apartment of Lillian Smith, the author of “Strange Fruit.”

As a young women she performed in concerts with members of the Philadelphia Symphony Orchestra. In her later years, she played piano and painted, “mostly for my own amusement.”

On a trip to Europe in 1929, she met Clark Clifford by chance on a steamer at Mainz on the Rhine River. They met again at a casino in Switzerland, and in 1931 they were married in Boston. In the early years of their marriage, they lived in St. Louis, where he practiced law.

In Washington, Mrs. Clifford did the interior design and decorating of the early 19th century farmhouse she and her husband purchased in 1950 in Bethesda. She also decorated her husband’s law offices and his office at the Pentagon, when he served as secretary of Defense in the final months of the Johnson administration. Mrs. Clifford served as a 1965 presidential inaugural ball

chairwoman.

Mr. Clifford died in 1998. Survivors include three daughters, Faith Christian of Chico, Calif., Dr. Joyce C. Burland of Halifax, Vt., and Randall C. Wright of Baltimore; 12 grandchildren; and 19 great-grandchildren.

CLIFFORD, MARGERY KIMBALL

On Friday, April 14, 2000, MARGERY KIMBALL CLIFFORD. Wife of the late Honorable Clark Clifford; mother of Ms Faith Christian, Dr. Joyce Burland and Randall Wight. She is also survived by 12 grandchildren and 19 great-grandchildren. Friends may call at JOSEPH GAWLER’S SONS, 5130 Wisconsin Ave. at Harrison St., NW, on Sunday, April 30 from 5 to 8 p.m. Services will be held at All Saints Episcopal Church, 3 Chevy Chase Cir., Chevy Chase, MD on Monday, May 1 at 12 Noon. Interment Arlington National Cemetery. In lieu of flowers, memorial contributions may be made to the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI), Colonial Place #3, 2107 Wilson Blvd.,Arlington, VA 22201-3042.

Clifford, Clark Mcadams

- Born 12/25/1906, Died 10/10/1998,

- US Navy, Captain

- Res: Bethesda, Maryland,

- Section 7A, Grave 35, buried 10/27/1998

Clifford, Margery Kimball

- Born 04/20/1908, died 04/14/2000

- US Army, Corporal

- Section 7A, Grave 35, buried 05/01/2000

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard