15 July 2008:

When Dr. Michael E. DeBakey pushed forward with his groundbreaking research and maverick approach to medicine a half century ago, heart surgery was a medical marvel. Today, in part because of his contributions, it routinely saves thousands of lives each day.

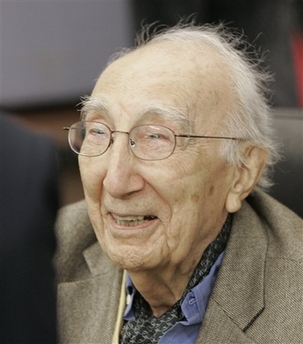

DeBakey, a world-famous cardiovascular surgeon who pioneered such now-common procedures as bypass surgery and invented a host of devices to help heart patients, died Friday night in Houston. He was 99.

According to a statement issued early Saturday by Baylor College of Medicine and Methodist Hospital, DeBakey died of “natural causes” shortly after arriving at the hospital. The hospital’s heart and vascular center bears his name.

DeBakey, whose career spanned more than 70 years, counted world leaders among his patients and helped turn Baylor from a provincial school into one of the nation’s great medical institutions.

“Dr. DeBakey’s reputation brought many people into this institution, and he treated them all: heads of state, entertainers, businessmen and presidents, as well as people with no titles and no means,” said Ron Girotto, president of The Methodist Hospital System.

A tireless worker and stern taskmaster, DeBakey performed more than 60,000 heart surgeries during his career and had scores of patients under his care at any one time.

Among his patients were presidents Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon, former Russian President Boris Yeltsin, the Shah of Iran, King Hussein of Jordan, Turkish President Turgut Ozal and Nicaraguan leader Violetta Chamorro.

But he said celebrities didn’t get special treatment on the operating table: “Once you incise the skin, you find that they are all very similar.”

At an April ceremony in Washington in which DeBakey was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal, Congress’ highest civilian honor, President Bush said the award placed the surgeon in the company of inventor Thomas Edison, Army doctor Walter Reed and Jonas Salk, who developed the polio vaccine.

“His legacy is holding the fragile and sacred gift of human life in his hands and returning it unbroken,” Bush said at the time.

Born to Lebanese immigrants on September 7, 1908, in Lake Charles, Louisiana, DeBakey his interest in medicine began while listening to physicians chat at his father’s pharmacy.

“I always knew I wanted to be a doctor. I just didn’t know what kind,” DeBakey once said.

He received his bachelor’s and medical degrees from Tulane University in New Orleans.

He recalled in 1999 that when he finished medical school in 1932, “there was virtually nothing you could do for heart disease. If a patient came in with a heart attack, it was up to God.”

In 1932, while in school, DeBakey invented the roller pump, which became the major component of the heart-lung machine, beginning the era of open-heart surgery. The machine takes over the function of the heart and lungs during surgery.

It was the start of a lifetime of innovation. DeBakey would go on to help pioneer the effort to develop artificial hearts and heart pumps to assist patients waiting for transplants, and help create more than 70 surgical instruments.

DeBakey was the first to perform replacement of arterial aneurysms and obstructive lesions in the mid-1950s. He later developed bypass pumps and connections to replace excised segments of diseased arteries.

In early 2006, at age 97, DeBakey underwent surgery for a damaged aorta — a procedure he developed.

“There is no question that he was one of the pioneers of cardiovascular surgery in the last half of the 20th century,” Dr. Denton Cooley, president and surgeon-in-chief at the Texas Heart Institute in Houston and a longtime DeBakey rival, said Saturday.

Cooley said one of DeBakey’s greatest legacies is “he influenced so many students to pursue careers in cardiovascular surgery.”

DeBakey’s former colleagues were among those who gathered Saturday at the still-uncompleted DeBakey Library at the Baylor College of Medicine to remember him.

“He took risks that others might not take to advance medicine and to prove the value of the procedures,” said Dr. Bobby R. Alford, chancellor of the Baylor College of Medicine. “He had impeccable judgment.”

DeBakey served as chairman of the President’s Commission on Heart Disease, Cancer and Stroke during Johnson’s administration and helped establish the National Library of Medicine. He was the author of more than 1,000 medical reports, papers, chapters and books on surgery, medicine and related topics.

In 1953, he performed the first Dacron graft to replace part of an occluded artery. In the 1960s, he began coronary arterial bypasses.

In 1962, DeBakey received a $2.5 million grant to work on an artificial heart that could be implanted without being linked to an exterior console. Four years later, he was the first to successfully use a partial artificial heart — a left ventricular bypass pump.

Dr. Christiaan Barnard in South Africa performed the first human heart transplant in history in late 1967. In the United States, DeBakey was among the first to begin performing the transplants, but death rates were high because the recipients’ bodies rejected the new organs.

The advent of a new anti-rejection drug, cyclosporine, gave new impetus to organ transplants in the 1980s. In 1984, DeBakey performed his first heart transplant in 14 years.

In the late 1990s, DeBakey took an active role in creating the Michael E. DeBakey Heart Institute at Hays Medical Center in Hays, Kansas.

DeBakey’s first wife, Diana Cooper DeBakey, died of a heart attack in 1972. He is survived by his second wife, Katrin Fehlhaber, their daughter, and two of his four sons from his first marriage.

15 July 2008:Dr. Michael E. DeBakey, whose innovative heart and blood vessel operations made him one of the most influential doctors in the United States, died Friday night in Houston, where he lived. He was 99.

His death, at the Methodist Hospital, was of natural causes, according to a statement released by the hospital and Baylor College of Medicine, where Dr. DeBakey was chancellor emeritus.

“Many consider Michael E. DeBakey to be the greatest surgeon ever,” the Journal of the American Medical Association said in 2005. By the time Dr. DeBakey stopped a regular surgical schedule, when he was in his 80s, he had performed more than 60,000 operations. He also made Houston a major center for heart surgery and research and turned Baylor into one of the nation’s great medical institutions.

Dr. DeBakey’s surgical innovations have become common practice today and have saved tens of thousands of lives. An early invention, the roller pump, devised while he was in medical school in the 1930s, became the central component of the heart-lung machine, which takes over the functions of the heart and lungs during surgery by supplying oxygenated blood to the brain. It helped inaugurate the era of open-heart surgery.

One of Dr. DeBakey’s innovations helped preserve his own life in 2006, when he underwent surgery to repair a torn aorta. He had devised the operation 50 years earlier. Afterward, he spent months making what he called a miraculous recovery and then returned to his office and an active schedule.

Yet he achieved his fame as much for what he did outside the operating room as what he did in it. His care of ailing world leaders, like President Boris N. Yeltsin of Russia, made headlines. And with organizational and political skills and energy as enormous as his pride, Dr. DeBakey traveled the world well into advanced age, lecturing and helping to build cardio-vascular centers. In 2005 alone he made four international trips.

A number of his surgical innovations and observations were initially ridiculed. While working at Tulane University in New Orleans in 1939, Dr. DeBakey and Dr. Alton Ochsner made one of the first links between cigarette smoking and lung cancer. Many prominent doctors derided the concept. Then, in 1964, the surgeon general documented the link.

Dr. DeBakey went on to discover — again in the face of professional skepticism — that Dacron grafts were excellent substitutes for damaged parts of arteries; the finding allowed surgeons to repair previously inoperable aneurysms of the aorta in the chest and abdomen.

Dr. DeBakey popularized — if he did not originate — operations to bypass blocked arteries in the neck, legs and heart. They have since been performed on millions of patients around the world. He was also a leader in developing mechanical devices to assist failing hearts.

In the cold war, Dr. DeBakey made about 20 visits to Moscow to lecture. The trust he earned helped shape recent history when, in a consultation, he determined that Yeltsin, who had fallen ill during a re-election campaign in 1996, could undergo coronary bypass surgery. Yeltsin’s doctors had contended that the president could not survive an operation, Dr. DeBakey said.

That consultation was credited with saving Yeltsin’s presidency, if not his life. (Yeltsin died last year at 76.)

“Calling in Dr. DeBakey was very important, a signal that he was in very serious condition, and consulting with a world leader in surgery this way was almost unthinkable in the Soviet period,” said Marshall I. Goldman, a Russian expert and senior scholar at Harvard.

Dr. DeBakey was also credited with transforming the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston from a provincial school into a leading educational and research institution. In 1948, when he arrived from Tulane to become chairman of Baylor’s department of surgery, he found the department on academic probation and broke.

In World War II, Dr. DeBakey helped modernize battlefield surgery by urging that doctors be moved from hospitals to the front lines, where only first aid had previously been given. Dr. DeBakey said that he and others created early versions of what became the mobile army surgical hospital, or MASH unit, in the Korean War. For changing the strategy of treating the wounded, the Army awarded him the Legion of Merit.

Dr. DeBakey also helped develop a medical program to care for returning war veterans. The Veterans Affairs hospital in Houston is named for him. And he was a driving force in rejuvenating the National Library of Medicine in Bethesda, Maryland, and turning it into the world’s leading repository of medical information.

Dr. DeBakey advised a number of presidents about health issues and, he said, consulted in the personal care of two of them: Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard M. Nixon. Even though Dr. DeBakey was on Nixon’s enemies list, the president invited him to the White House for a briefing after one of Dr. DeBakey’s visits to the Soviet Union.

Dr. DeBakey attributed his longevity in part to never having smoked and to genes that helped other members of his family live into their 90s. A relatively short man who looked 20 years younger than his age, he could fit into his Army uniform in his later years despite a lack of regular physical exercise, he said.

Even in his 90s, Dr. DeBakey arose at 5 a.m. every day, wrote in his study for two hours and then drove, often in a sports car, to the hospital, where he stayed until 6 p.m. After dinner, he usually returned to his library for more reading or writing before retiring after midnight.

Dr. Michael DeBakey addressed the press on April 3, 1980, after returning from Egypt, where he performed surgery on the deposed Shah of Iran.

Michael Ellis DeBakey never lost the Southern drawl he acquired growing up in Lake Charles, Louisiana. He was born on September 7, 1908, the oldest of five children of Lebanese-Christian immigrants who moved to the United States to escape religious intolerance in the Middle East. His parents chose Cajun country because French was spoken there, as it had been in Lebanon.

Dr. DeBakey credited much of his surgical success to his mother, Raheeja, for teaching him to sew, crochet and knit.

He was inspired to become a doctor from chats with local physicians while he worked at a pharmacy owned by his father, Shaker Morris DeBakey, who also owned rice farms.

While attending schools in Lake Charles and earning undergraduate and medical degrees from Tulane, he played the saxophone and clarinet in a band.

As a medical student, he showed a gift for innovation when an instructor asked him to find a pump to study pulse waves in arteries. From library research, he fashioned older pumps and rubber tubing into one that served the instructor’s purpose, calling it a roller pump.

This was before the time of blood banks, so Dr. DeBakey used the pump to transfuse blood directly from a donor to a patient. The pump was later adapted for use in the heart-lung machine.

After finishing his training at Charity Hospital in New Orleans in 1935, Dr. DeBakey started out as a general surgeon. At the time, few doctors specialized in heart and chest surgery. Young American doctors who aspired to academic careers typically sought further training in Europe. Dr. DeBakey enrolled at the University of Strasbourg in France and then the University of Heidelberg in Germany.

In his first weeks at Baylor, in 1948, Dr. DeBakey found that a promised affiliation with a hospital in Houston had fallen through and that the hospital’s doctors would accordingly not let him operate on their patients. With nowhere to teach young doctors, Dr. DeBakey was about to resign from Baylor.

But then the Truman administration asked him to help transfer Houston’s Navy hospital to the Veterans Administration. Seizing on the opportunity, he stayed on at Baylor to help make the veterans hospital Baylor’s first official hospital affiliate and build Houston’s first surgical residency program.

Dr. DeBakey had a knack for recruiting good surgeons who played key roles in many of his successes. One was Dr. Denton A. Cooley, who was Dr. DeBakey’s protégé until a rift left them bitter rivals.

In his public and professional lectures, Dr. DeBakey, an inveterate name-dropper, often showed photographs of his celebrated patients and spoke about their ailments. Among these notables were the deposed shah of Iran, Mohammed Reza Pahlavi; the duke of Windsor, the former King Edward VIII of England; Marlene Dietrich; Joe Louis; Leo Durocher, the baseball manager; and Jerry Lewis. His spacious office in Houston and the long corridors leading to it were lined with framed awards and pictures autographed by many of his patients.

The main focus of Dr. DeBakey’s surgical innovations was arteriosclerosis, a systemic disease in which fatty deposits can damage arteries feeding the heart and other tissues, leading to heart attacks, strokes and loss of limbs.

When Dr. DeBakey began his career, surgeons could do little for arteriosclerosis. He was a leader among those who demonstrated otherwise.

Dr. Allan D. Callow, a vascular surgeon and emeritus professor of surgery at Tufts University, said Dr. DeBakey had recognized that the damage from arteriosclerosis was often limited to critical areas in arteries and that these areas could be cut out or bypassed surgically.

In 1952, Dr. DeBakey successfully repaired an aortic aneurysm — a ballooning of an artery — by cutting out the damaged segment in the abdomen and replacing it with a graft from a cadaver. In 1953, he successfully repaired a blocked carotid artery in the neck. The blockage threatened to cause a stroke by choking off blood flow to part of the brain.

Luck played a big role in one of Dr. DeBakey’s major innovations.

Seeking to use synthetic instead of cadaver grafts, he went to a department store to buy some nylon. The store had run out of it, so a clerk suggested a new product, Dacron. Dr. DeBakey liked its feel, bought a yard and then used his wife’s sewing machine — he was married to the former Diana Cooper at time — to create his first artificial arterial patches and tubes.

He went on to collaborate with a textile engineer in Philadelphia to produce Dacron arterial grafts in large numbers.

Dacron turned out to last for decades as a surgical graft; nylon, by contrast, broke down after about a year.

Many doctors initially scoffed at Dr. DeBakey’s claim about Dacron, in part because he had a tendency, like a number of other surgeons, not to report failures. But when the critics went to Houston, they found he was operating on many patients and was far ahead of them.

That work won Dr. DeBakey a Lasker Award, the country’s most prestigious biomedical prize, in 1963. He was cited for a number of accomplishments that were “responsible in a large measure for inaugurating a new era in cardiovascular surgery.”

In 1964, President Johnson appointed Dr. DeBakey chairman of the President’s Commission on Heart Disease, Cancer and Stroke, which went on to raise standards of care for these diseases.

Dr. DeBakey was a pioneer in performing coronary bypass operations. In one of his last lectures, at the New York Academy of Medicine in Manhattan in November 2005, Dr. DeBakey said that his team had performed the first successful coronary bypass operation, in 1964, but that it did not report it until 1974.

Critics say Dr. DeBakey was eager to claim credit for innovations or exaggerate his role in making them, but since no biography of Dr. DeBakey or thorough analysis of his hundreds of scientific papers has been published, it will be left to medical historians to resolve such controversies.

Shortly after Dr. Christiaan N. Barnard performed the first human heart transplant in 1967, in Cape Town, South Africa, Dr. DeBakey followed, somewhat warily. His team was the first to transplant four organs (a heart, two kidneys and a lung) from one donor to different recipients.

Realizing that the demand for human heart transplants would outstrip the supply, Dr. DeBakey pursued the development of a total artificial heart as well as a partial one, known as a ventricular assist device, or VAD.

Dr. DeBakey is believed to have been the first to use a VAD successfully. Over 10 days in 1966, he weaned a woman from a heart-lung machine after heart surgery and then removed the device when her heart function improved. She died in an automobile accident several years later.

A number of such assisting devices, including a small one bearing Dr. DeBakey’s name, are now marketed or are being tested among patients with severe heart failure. The use of the total artificial heart that Dr. DeBakey was developing with Dr. Domingo S. Liotta led to a widely publicized scandal in 1969. On walking into a meeting at the National Institutes of Health, which was paying for the research, Dr. DeBakey was shocked to learn that hours earlier Dr. Cooley, his former colleague, had implanted an artificial heart in a patient for the first time. The device was the one the DeBakey team had been testing on calves.

The government ordered Baylor to investigate the unauthorized use of the experimental device. Using the artificial heart on the patient, Haskell Karp, was premature, Dr. DeBakey said, because of “discouraging results” in calves. He later called Dr. Cooley’s action a “childish” effort to claim a medical first.

Dr. Cooley, who had moved to another nearby Baylor institution, St. Luke’s Hospital, had never tested the device on animals and said he had implanted it as a desperate measure to keep Mr. Karp alive until he could do a transplant. But others contended that Dr. Cooley had secretly been planning to use the device for several months.

The American College of Surgeons censured Dr. Cooley, who resigned from Baylor, and for almost 40 years the two master surgeons rarely spoke, maintaining perhaps the most famous feud in medicine. But it ended last year, in a surprise reconciliation, when the two men warmly shook hands at a ceremony at St. Luke’s in which Dr. DeBakey received a lifetime achievement award from the Denton A. Cooley Cardiovascular Surgical Society.

Dr. DeBakey said his ties to the former Soviet Union began after he befriended a small group of Soviet doctors who sat by themselves at a surgical meeting in Mexico in the 1950s. Dr. DeBakey took them to lunch and invited them to watch him operate in Houston on their way home. Later, they invited Dr. DeBakey to speak in the Soviet Union.

In 1973, Dr. DeBakey went to Moscow to operate on Mstislav Keldysh, a nuclear scientist and president of the Soviet Academy of Science. A year later, the Academy of Medical Sciences of the U.S.S.R. elected Dr. DeBakey a foreign member.

For 30 years, from 1964 to 1994, Dr. DeBakey served as chairman of the Albert and Mary Lasker Foundation’s medical research awards jury. Contacts Dr. DeBakey made through the foundation led to referrals from around the world.

As a shrewd medical politician, Dr. DeBakey called on grateful patients and their families to influence national legislation creating the National Library of Medicine and then ensuring that it would be part of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland.

Dr. DeBakey never shied from controversy.

In the early 1960s, he attended a press conference at the White House with President John F. Kennedy to support the creation of the federal Medicare health insurance plan, bucking the American Medical Association, which had given him its Distinguished Service award in 1959. The Medicare legislation passed in 1965 under President Johnson.

Dr. DeBakey said his greatest professional disappointment was in not solving the mystery of atherosclerosis; he never accepted cholesterol as the dominant factor in producing the disease. In the 1980s, Dr. DeBakey was among the first to explore whether a virus or other infectious agent might lead to arteriosclerosis, a link scientists continue to explore.

In 1969, Johnson awarded Dr. DeBakey the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest honor given a United States citizen. In 1987, President Ronald Reagan awarded him the National Medal of Science. In April, he received the Congressional Gold Medal, Congress’s highest civilian honor, in a ceremony attended by President Bush.

Dr. DeBakey’s first wife, Diana, died in 1972. His survivors include his second wife, the former Katrin Fehlhaber, who had been a film actress in Germany; their daughter, Olga-Katarina; two sons from his first marriage, Michael and Dennis; two sisters; and a number of grandchildren. Two sons, Ernest and Barry, died earlier. Dr. DeBakey was a perfectionist, intolerant of incompetence, sloppy thinking and laziness. Before mellowing in his later years, he had a reputation for sometimes tyrannical behavior in firing assistants for making relatively minor errors like cutting a suture to the wrong length.

“If you were on the operating table,” Dr. DeBakey said, “would you want a perfectionist or somebody who cared little for detail?”

Dr. Jeremy R. Morton, a retired heart surgeon in Portland, Maine, who trained under Dr. DeBakey, said: “He could be sweet as dripping honey when it came to patients and medical students, but could be brutal with surgical residents.

“I guess he was trying to make us tough.”

16 July 2008:

DeBakey to be buried at Arlington National Cemetery

Houston Business JournalThe burial service for Dr. Michael E. DeBakey will be held at 10 a.m. on July 18, at Arlington National Cemetery.

The memorial service is today at 1 p.m. at Co-Cathedral of the Sacred Heart, 1111 St. Joseph’s Parkway. The service is open to the public.

Video and still cameras will be prohibited inside the church.

Ten speakers will give reflections, and Dr. Robert Schuller, Crystal Cathedral, will provide the message. The invocation will be given by The Most Reverend Joseph A. Fiorenza, Archbishop Emeritus of Galveston-Houston. His Eminence Daniel Cardinal DiNardo, Archbishop of Galveston-Houston, will give the benediction.

Among those giving reflections are: Dr. Richard E. Wainerdi, president, the Texas Medical Center; U.S. Representative Al Green and the heads of several Med Center institutions.

DeBakey died at age 99 on July 11, 2008, of natural causes at The Methodist Hospital in Houston.

In a career that began more than 70 years ago, DeBakey performed more than 60,000 heart surgeries. The famed Houston heart surgeon served as medical adviser to U.S. presidents and foreign heads of state.

Acknowledged as the father of modern cardiovascular surgery, the physician was credited with a number of medical firsts and served as chancellor emeritus of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

16 July 2008:

HOUSTON, Texas – Pioneering heart surgeon Michael DeBakey was remembered at a memorial service as not only a brilliant physician and medical innovator but also as friend and humanitarian.

During a two-hour service at a Houston Catholic church on Wednesday, friends and colleagues detailed DeBakey’s rise to becoming the father of modern heart surgery.

Mixed in with those accolades were heartfelt stories that detailed DeBakey’s personal life, everything from his love of gumbo to his learning to play the clarinet in three months to his baby-sitting abilities.

DeBakey died last Friday at the age of 99.

DeBakey, who served in the U.S. Army during World War II, was scheduled to be buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia on Friday.

16 July 2008:

HOUSTON, Texas – Dr. Michael DeBakey will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery Friday now that his memorial service has been held in Houston.

During a two-hour ceremony, Debakey — who died Friday at age 99 — was remembered as a pioneering heart surgeon who was also a medical innovator, friend, and humanitarian. Some of those at the service were patients who say they benefited from the surgical techniques he helped create.

DeBakey became the first Houston resident yesterday to lie in repose at City Hall. He was dressed in surgical garb.

Among DeBakey’s patients over the years were three presidents: John Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, and Richard Nixon. He qualifies for burial at Arlington because of his Army service during World War II.

Dr. DeBakey was a Colonel in the United States Army from 1942-1946. He was granted an exception to the interment policy by the Secretary of the Army on July 15, 2008, because of all his extraordinarily exceptional service given in the interest of advancing medical technologies and the care that has resulted in the saving of lives of our Service Members.

28 July 2008:

By JULIE MASON

Courtesy of the Houston Chronicle

With military honors on a sun-dappled hillside, pioneering heart surgeon and World War II Army veteran Dr. Michael Ellis DeBakey of Houston was buried today at Arlington National Cemetery.

A small, solemn clutch of attendees at the graveside included DeBakey’s widow, Katrin DeBakey; their daughter Olga, Defense Secretary Robert Gates and Veterans Administration Secretary James Peake.

Army Chaplain Harry Rauch III, reading from John 14:1, said, “Let not your heart be troubled: believe in God, believe also in me. In my Father’s house are many mansions; if it were not so, I would have told you; for I go to prepare a place for you.”

DeBakey, who achieved the rank of Colonel in the Army, died last week in Houston at age 99.

In World War II, DeBakey served in the U.S. Army Surgeon General’s Office. He was instrumental in setting up the earliest MASH units, and later a network of health services for returning veterans which grew into the Veterans Administration.

The morning internment was largely private, with reporters and news cameras kept far back from the service. A crew from the Veterans Administration videotaped the service for the family.

DeBakey’s hearse-carried casket arrived at the burial site shortly after 10 a.m., followed by a cortege of dignitaries, family, friends and colleagues, including several from Texas.

With precise formality, military aides lifted the flag-covered coffin from the vehicle and slowly carried it toward its resting spot. Overheard, birds sang and a nearby firing party waited in formation to deliver the traditional salute.

Rauch, a lieutenant colonel, read from a sheet many of DeBakey’s accomplishments in his life, including his contributions to medicine and particularly heart surgery.

DeBakey was born in Lake Charles, La., and graduated from Tulane University in 1930. At Tulane Medical School, he distinguished himself as a gifted surgical student. When he died, DeBakey was chancellor emeritus of the Baylor College of Medicine.

Among DeBakey’s former colleagues attending the gravesite rites Edgar Tucker, director of the DeBakey VA Medical Center.

From Baylor College of Medicine, Dr. Peter Traber, president and CEO; Dr. William Butler, chancellor emeritus; Dr. Bobby Alford, chancellor; Dr. Jim Pool, Baylor faculty; and Claire Bassett, vice president of public affairs and federal government relations, also attended.

Rauch praised “our comrade in arms” and thanked DeBakey’s widow for her husband’s service. A firing party on an adjacent hillside fired a volley of salute, and a bugler played the mournful “Taps.”

In keeping with military honors, the flag, held taut over the casket during the service, was folded into a traditional, triangular shape and handed to Gates, who knelt before DeBakey’s widow and presented it to her, along, with a few quiet words.

Throughout the service, Olga DeBakey sat erect with her head high, hands folded in her lap.

DeBakey, whose work included treating celebrities such as the Duke of Windsor, the Shah of Iran, King Hussein of Jordan and Presidents Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon, had a long and distinguished career as a medical pioneer and a public policy statesman.

Earlier this year he was awarded one of the nation’s highest civic honors, the Congressional Gold Medal.

18 July 2008

Medical pioneer buried at Arlington cemetery

Defense Secretary Robert Gates lowered himself on one knee at Arlington National Cemetery on Friday and presented the flag from the coffin of medical innovator Dr. Michael DeBakey to his wife, Katrin.

Gates’ presence and that of Veterans Affairs Secretary James Peake at the graveside burial ceremony signaled the prominence of DeBakey, who achieved immortality long before he died.

As a young boy, DeBakey devoured an Encyclopedia Brittanica set and then invented so many medical devices, procedures, tools and concepts that he became an encyclopedia entry himself.

DeBakey “viewed death as a personal enemy,” presiding Chaplain Harry Rauch III said Friday. DeBakey accepted the reality that everyone must die but insisted that death should be fought all the time, Rauch said.

DeBakey died last Friday at the age of 99.

His World War II service entitled him to be buried in Arlington National Cemetery, but his grave is not among those of medical doctors. That area is full.

DeBakey was buried in plot 399-A, Section 34, an area where General John J. Pershing and Ira Hayes, one of the Iwo Jima flag raisers, also lay. His nearest neighbor is World War II veteran and Bronze Star winner Edward Curtis Franklin, who died in 1958 at age 43.

The burial site seemed deserved for the man whose work led to military units that deliver lifesaving surgeries on the war front and for the research on veterans health problems that became the Veterans Administration, now Veterans Affairs.

The lives of many of the hundreds of thousands also buried at Arlington were cut short in battle, but a number of the other departed veterans there surely benefited from the heart bypass, rolling pump, medical tools or other procedures and devices that DeBakey innovated.

The sun glinted off the medals of a soldier as he handed to Gates the American flag folded with a precision DeBakey would have appreciated. “In life he honored the flag,” Rauch said. “In death the flag honors him.”

DeBAKEY, MICHAEL ELLIS

- COL, US ARMY

- DATE OF BIRTH: 09/07/1908

- DATE OF DEATH: 07/11/2008

- DATE OF BURIAL: 07/18/2008

- SECTION 34 SITE: 399-A

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard