Born in Massachusetts, he was a Civil War veteran who was wounded three times in battle and who met President Abraham Lincoln on one of the President’s visits to the front.

He taught law at Harvard, sat on the Massachusetts Supreme Court for twenty years and served for thirty years on the United States Supreme Court, where he helped President Franklin D. Roosevelt select his own successor.

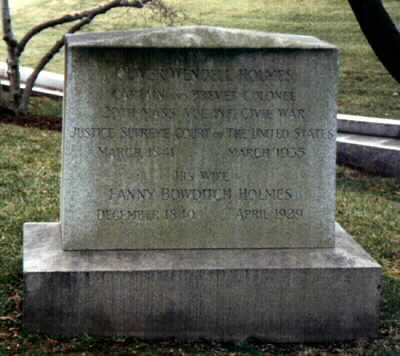

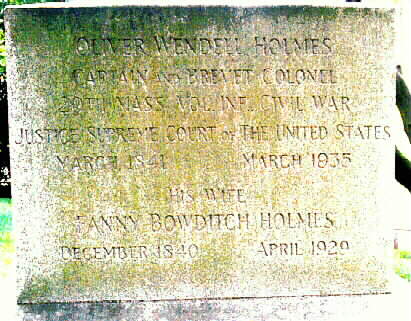

An interesting fact is that he had ben appointed to the Court by President Theodore Roosevelt, who was disappointed in many of his decisions. He was known on the Court as “The Great Dissenter” because of the brilliant legal reasoning found in his written opinions. He retired from the Court on January 12, 1932 and was the oldest man to have ever served on the court. He died in Washington, D. C. on March 6, 1935 and was buried in Section 5 of Arlington National Cemetery.

His wife, Fannie Bowditch Dixwell Holmes (December 1840-April 1929), whose burial was arranged by Chief Justice William Howard Taft because Holmes was too shy to ask for the honor, is buried with him.

He is buried in Section 5 of Arlington National Cemetery, near the graves of fellow Supreme Court Justices William O. Douglas, Potter Stewart, Thurgood Marshall and William J. Brennan.

“I have a lovely spot in Arlington toward the bottom of the hill where the house is, with pine trees, oak, and tulip all about, and where one looks to see a deer trot out (although of course there are no deer). I have ordered a stone of the form conventional for officers which will bear my name, Bvt. Col. and Capt. 20th Mass. Vol. Inf. Civil War- Justice Supreme Court, U.S.-March 1841- His wife Fanny Holmes and the dates. It seemed queer putting up my own tombstone-but these things are under military direction and I suppose it was necessary to show a soldiers’ name to account for my wife”.

A few years before his death, May 29, 1931, Holmes wrote to his friend Lewis Einstein:

“I shall go out to Arlington tomorrow, Memorial Day, and visit the gravestone with my name and my wife’s on it, and be stirred by the military music, and, instead of bothering about the Unknown Soldier shall go to another stone that tells beneath it are the bones of, I don’t remember the number but two or three thousand and odd, once soldiers gathered from the Virginia fields after the Civil War. I heard a woman say there once, ‘They gave their all. They gave their very names.’ Later perhaps some people will come in to say goodbye.”

March 6, 1935

OBITUARY

Washington Holds Bright Memories of Justice Holmes’s Long and Useful Life

American Legend in Life of Holmes

Soldier, Jurist and Philosopher, He Sprang From New England’s

Cultural Dominance

Rare Genius for the Law

‘A Deserving Fame Never Dimmed and Always Growing,’ Said Justice Hughes

As Justice Holmes grew old he became a figure for legend. Eager young students of history and the law, with no possibility of an introduction to him, made pilgrimages to Washington merely that they might remember at least the sight of him on the bench of the Supreme Court. Others so fortunate as to be invited to his home were apt to consider themselves thereafter as men set apart. Their elders, far from discouraging this attitude, strengthened it.

A group of leading jurists and liberals filled a volume of essays in praise of him, and on the occasion of its presentation Chief Justice Hughes said:

“The most beautiful and the rarest thing in the world is a complete human life,

unmarred, unified by intelligent purpose and uninterrupted accomplishment, blessed by great talent employed in the worthiest activities, with a deserving fame never dimmed and always growing. Such a rarely beautiful life is that of Mr. Justice Holmes.”

Born in Boston in 1841

He was born on March 8, 1841, in Boston. The cultural dominance of New England was at its height. The West was raw, great parts of it wilderness as yet only sketchily explored. A majority of the nation’s citizens still considered the enslavement of Negroes as the operation of a law of God, and Darwin had not yet published his “Origin of Species.”

The circumstances of his birth were fortunate. His father, Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes, was of New England’s ruling caste and the atmosphere of his home was at once brahminical, scientific and literary. They boy was to start each day at that “autocratic” breakfast table where a bright saying won a child a second helping of marmalade.

The boy was prepared for Harvard by E. S. Dixwell of Cambridge. He was fortunate again in this. Well-tutored, he made an excellent record in college. His intimacy with Mr. Dixwell’s household was very close. His tutor’s daughter, Fanny Dixwell, and he fell in love with each other and later they were married.

Fort Sumter was fired on and President Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers. Young Holmes, 20 years old and shortly to be graduated from Harvard with the class of ’61, walked down Beacon Hill with an open Hobbe’s “Leviathan” in his hand and learned that he was commissioned in the Twentieth Massachusetts Volunteers.

The regiment, largely officered by young Harvard men and later to be known as the “Harvard Regiment,” was ordered South and into action at Ball’s Bluff. There were grave tactical errors and the Union troops were driven down the cliff on the Virginia shore and into the Potomac. Men trying to swim to safety were killed and wounded men were drowned.

Lieutenant Holmes, with a bullet through his breast, was placed in a boat with dying men and ferried through saving darkness to the Maryland shore.

His wound was serious, but the sufferer was young and storng. For convalescence he was returned to Boston. On his recovery he returned to the front.

At Antietam a bullet pierced his neck and again his condition was critical. Dr. Holmes, on learning the news, set out to search for his son. The search lasted many worried days and brought the father close to the lines at several points. He found his son already convalescent and brought him back to Boston, where he wrote his experiences under the title, “My Hunt for the Captain,” an article that was enthusiastically received as bringing home to Boston a first-hand picture of the trials of war directly behind the lines.

Wounded a Third Time

Back at the front, the young officer was again wounded. A bullet cut through tendons and lodged in his heel. This wound was long in healing and Holmes was retired to Boston with the brevet ranks of Colonel and Major.

The emergency of war over, his life was his own again. There was the question, then, of what to do with it. Writing appealed to him. He had been class poet and prize essayist in college. But he finally turned to law, although it was long before he was sure that he had taken the best course.

“It cost me some years of doubt and unhappiness,” he said later, “before I could say to myself: ‘The law is part of the universe–if the universe can be thought about, one part must reveal it as much as another to one who can see that part. It is only a question if you have the eyes.'”

Philosophy and William James helped him find his legal eyes while he studied in Harvard Law School and James, a year younger, was studying medicine. Through long nights they discussed their “dilapidated old friend the Kosmos.” James later was to write in affectionate reminiscence of “your whitely lit-up room, drinking in your profound wisdom, your golden jibes, your costly imagery, listening to your shuddering laughter.”

But while James went on, continuing in Germany his search for the meanings of the universe, Holmes decided that “maybe the universe is too great a swell to have a meaning,” that his task was to “make his own universe livable,” and he drove deep into the study of the law.

He took his LL. B. in 1866 and went to Europe to climb some mountains. Early in 1867 he was admitted to the bar and James noted that “Wendell is working too hard.” The hard work brought results. In 1870 he was made editor of the American Law Review.

Two years later, on June 17, 1872, he married Fanny Bowditch Dixwell and in March of the next year became a member of the law firm of Shattuck, Homes & Munroe, resigning his editorship but continuing to write articles for The Review. In that same year, 1873, his important edition of Kent’s Commentaries appeared.

His papers, particularly one on English equity, which bristled with citations in Latin and German, showed that he was a master scholar where mastery meant labor and penetration. It was into these early papers that he put the fundamentals of an exposition of the law that he was later to deliver in Lowell Lectures at Harvard and to publish under the title, “The Common Law.” In this book, to quote Benjamin N. Cardozo, he “packed a whole philosophy of legal method into a fragment of a paragraph.”

The part to which Judge Cardozo referred reads:

“The life of the law has not been logic; it has been experience. The felt necessities of the time, the prevalent moral and political theories, intuitions of public policy avowed or unconscious, even with the prejudices which judges share with their follow-men, have had a great deal more to do than the syllogism in determining the rules by which men should be governed. The law embodies the story of a nation’s development through many centuries, and it cannot be dealt with as if it contained only the axioms and corollaries of a book of mathematics.”

Judge Cardozo, commenting on this, wrote:

“The student of juristic method, bewildered in a maze of precedents, feels the thrill of a new apocalypse in the flash of this revealing insight. Here is the text to be unfolded. All that is to come will be development and commentary. Flashes there are like this in his earlier manner as in his latest, yet the flashes grow more frequent, the thunder peals more resonant, with the movement of the years.”

Makes His Debut as Judge

Holmes was only 39 years old when Harvard called him back to teach in her Law School and 41 when he became an Associate Justice on the Massachusetts Supreme Court bench.

So in that great period when Joseph H. Choate could call a Federal income tax “sheer communism,” the young Massachusetts justice could, with no bias, write dozens of dissenting opinions in which he expressed views that since have been molded into law.

He was Chief Justice on the Commonwealth bench when, in 1901, Theodore Roosevelt noted that Holmes’s “labor decisions” were criticized by “some of the big railroad men and other members of large corporations.” Oddly enough the successor of William McKinley thought that was “a strong point in Judge Holmes’s favor.”

In reference to this the President wrote to Henry Cabot Lodge:

“The ablest lawyers and greatest judges are men whose past has naturally brought them into close relationship with the wealthiest and most powerful clients and I am glad when I can find a judge who has been able to preserve his aloofness of mind so as to keep his broad humanity of feeling and his sympathy for the class from which he has not drawn clients.”

In further expression of this approval he in 1902 appointed Judge Holmes to the Supreme Court of the United States, an appointment that was confirmed by the Senate immediately and unanimously.

In a dissenting opinion written early in his career on the Supreme bench Justice Holmes bluntly told his associates that the case in hand had been decided by the majority on an economic theory which a large part of the country did not entertain, that general principles do not decide concrete cases, that the outcome depends on a judgment or institution more subtle than any articulate major premise.

A great struggle between the forces of Theodore Roosevelt and the elder J. P. Morgan began on March 10, 1902, when the government filed suit in the United States Circuit Court for the district of Minnesota charging that the Great Northern Securities Company was “a virtual consolidation of two competing transcontinental lines” whereby not only would “monopoly of the interstate and foreign commerce, formerly carried on by them as competitors, be created,” but, through use of the same machinery, “the entire railway systems of the country may be absorbed, merged, and consolidated.”

In April, 1903, the lower court decided for the government and 8,000 pages of records and briefs went to the United States Supreme Court for final review. On March 14, 1904, the high court found for the government, with Justice Holmes writing in dissent.

He held that the Sherman act did not prescribe the rule of “free competition among those engaged in interstate commerce,” as the majority held. It merely forbade “restraint of trade or commerce.” He asserted that the phrases “restraint of competition” and “restraint of trade” did not have the same meaning; that “restraint of trade,” which had “a definite and well-established significance in the common law, means and had always been understand to mean, a combination made by men engaged in a certain business for the purpose of keeping other men out of that business.”

The objection to trusts was not the union of former competitors, but the sinister power exercised, or supposed to be exercised, by the combination in keeping rivals out of the business, he said. It was the ferocious extreme of competition with others, not the cessation of competition among the partners, which was the evil feared.

“Much trouble,” he continued, “is made by substituting other phrases, assumed to be equivalent, which are then argued from as if they were in the act. The court below argued as if maintaining competition were the express purpose of the act. The act says nothing about competition.”

It was at this time that John Morley visited America and returned to England with the affirmation that in Justice Homes America possessed the greatest judge of the English-speaking world. Time has reinforced the emphasis. In his years on the Supreme Court bench he had done more to mold the texture of the Constitution than any man since John Marshall revealed to the American people what their new Constitution might imply.

Matthew Arnold, in his essay on the study of poetry, says that the best way to separate the gold from the alloy in the coinage of the poets is by the test of a few lines carried in the thoughts.

Excerpts From Holmes’s Writings

From the opinions and other writings of Justice Holmes the following lines are some that might be used for this test:

“When men have realized that time has upset many fighting faiths, they may come to believe even more than they believe the very foundations of their own conduct that the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas — that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market, and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes can be carried out. That, at any rate, is the theory of our Constitution. It is an experiment, as all life is an experiment.”

“In the organic relations of modern society it may sometimes be hard to draw the line that is supposed to limit the authority of the Legislature to exercise or delegate the power of eminent domain. But to gather the streams from waste and to draw from them energy, labor without brains, and so to save mankind from toil that it can be spared, is to supply what, next to intellect, is the very foundation of all our achievements and all our welfare. If that purpose is not public, we should be at a loss to say what is.”

“The Fourteenth Amendment does not enact Mr. Herbert Spencer’s social tatics.”

“While the courts must exercise a judgment of their own, it by no means is true that every law is void which may seem to the judges who pass upon it, excessive, unsuited to its ostensible end, or based upon conceptions of morality with which they disagree. Considerable latitude must be allowed for difference of view as well as for possible peculiar conditions which this court can know but imperfectly, if at all. Otherwise a Constitution, instead of embodying only relatively fundamental rules of right, as generally understood by all English-speaking communities, would become the partisan of a particular set of ethical or economic opinions, which by no means are held semper ubique et ab omnibus.”

His contribution to American life was not limited to the law. He lived as he advised others to live, in the “grand manner.” He sought quality rather than quantity of experience and knowledge of his success in living helped others to find it, too.

On his ninetieth birthday he delivered a short radio speech in reply to tributes from Chief Justice Hughes and other leaders of the American bar.

From a Latin poet he quoted the words:

“Death plucks my ears and says, ‘Live — I am coming.'”

And in one line he gave the core of a life philosophy:

“To live is to function; that is all there is to living.”

Left Bench January 12, 1932

Justice Holmes resigned on January 12, 1932. “The time has now come and I bow to the inevitable,” he wrote to the President. He left, amid national regret, almost thirty years after he had been appointed to the Supreme Court bench.

Soon after that, in a message to the Federal Bar Association, Justice Holmes wrote:

“I cannot say farewell to life and you in formal words. Life seems to me like a Japanese picture which our imagination does not allow to end with the margin. We aim at the infinite, and when our arrow falls to earth it is in flames.

“At times the ambitious ends of life have made it seem to me lonely, but it has not been. You have given me the companionship of dear friends who have helped to keep alive the fire in my heart. If I could think that I had sent a spark to those who come after, I should be ready to say good-bye.”

Justice Holmes was an honorary member of the Honourable Society of Lincoln’s Inn, London, to which also belonged such men as Oliver Cromwell, William Pitt, Benjamin Disraeli and William Ewart Gladstone.

Soon after retiring, his salary was cut in two by reason of the economy law. It was restored to $20,000 a year a few months later, however, by special action of the Senate.

In the Fall of 1931 appeared the “Representative Opinions of Mr. Justice Holmes.”

Mrs. Holmes died on April 30, 1929.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.”In Our Youth Our Hearts Were Touched With Fire”

An address delivered for Memorial Day, May 30, 1884, at Keene, New Hampshire, before John Sedgwick Post No. 4, Grand Army of the Republic.

Not long ago I heard a young man ask why people still kept up Memorial Day, and it set me thinking of the answer. Not the answer that you and I should give to each other-not the expression of those feelings that, so long as you live, will make this day sacred to memories of love and grief and heroic youth–but an answer which should command the assent of those who do not share our memories, and in which we of the North and our brethren of the South could join in perfect accord.

So far as this last is concerned, to be sure, there is no trouble. The soldiers who were doing their best to kill one another felt less of personal hostility, I am very certain, than some who were not imperilled by their mutual endeavors. I have heard more than one of those who had been gallant and distinguished officers on the Confederate side say that they had had no such feeling. I know that I and those whom I knew best had not. We believed that it was most desirable that the North should win; we believed in the principle that the Union is indissoluable; we, or many of us at least, also believed that the conflict was inevitable, and that slavery had lasted long enough. But we equally believed that those who stood against us held just as sacred conviction that were the opposite of ours, and we respected them as every men with a heart must respect those who give all for their belief. The experience of battle soon taught its lesson even to those who came into the field more bitterly disposed. You could not stand up day after day in those indecisive contests where overwhelming victory was impossible because neither side would run as they ought when beaten, without getting at least something of the same brotherhood for the enemy that the north pole of a magnet has for the south–each working in an opposite sense to the other, but each unable to get along without the other. As it was then , it is now. The soldiers of the war need no explanations; they can join in commemorating a soldier’s death with feelings not different in kind, whether he fell toward them or by their side.

But Memorial Day may and ought to have a meaning also for those who do not share our memories. When men have instinctively agreed to celebrate an anniversary, it will be found that there is some thought of feeling behind it which is too large to be dependent upon associations alone. The Fourth of July, for instance, has still its serious aspect, although we no longer should think of rejoicing like children that we have escaped from an outgrown control, although we have achieved not only our national but our moral independence and know it far too profoundly to make a talk about it, and although an Englishman can join in the celebration without a scruple. For, stripped of the temporary associations which gives rise to it, it is now the moment when by common consent we pause to become conscious of our national life and to rejoice in it, to recall what our country has done for each of us, and to ask ourselves what we can do for the country in return.

So to the indifferent inquirer who asks why Memorial Day is still kept up we may answer, it celebrates and solemnly reaffirms from year to year a national act of enthusiasm and faith. It embodies in the most impressive form our belief that to act with enthusiam and faith is the condition of acting greatly. To fight out a war, you must believe something and want something with all your might. So must you do to carry anything else to an end worth reaching. More than that, you must be willing to commit yourself to a course, perhpas a long and hard one, without being able to foresee exactly where you will come out. All that is required of you is that you should go somewhither as hard as ever you can. The rest belongs to fate. One may fall-at the beginning of the charge or at the top of the earthworks; but in no other way can he reach the rewards of victory.

When it was felt so deeply as it was on both sides that a man ought to take part in the war unless some conscientious scruple or strong practical reason made it impossible, was that feeling simply the requirement of a local majority that their neighbors should agree with them? I think not: I think the feeling was right-in the South as in the North. I think that, as life is action and passion, it is required of a man that he should share the passion and action of his time at peril of being judged not to have lived.

If this be so, the use of this day is obvious. It is true that I cannot argue a man into a desire. If he says to me, Why should I seek to know the secrets of philosophy? Why seek to decipher the hidden laws of creation that are graven upon the tablets of the rocks, or to unravel the history of civilization that is woven in the tissue of our jurisprudence, or to do any great work, either of speculation or of practical affairs? I cannot answer him; or at least my answer is as little worth making for any effect it will have upon his wishes if he asked why I should eat this, or drink that. You must begin by wanting to. But although desire cannot be imparted by argument, it can be by contagion. Feeling begets feeling, and great feeling begets great feeling. We can hardly share the emotions that make this day to us the most sacred day of the year, and embody them in ceremonial pomp, without in some degree imparting them to those who come after us. I believe from the bottom of my heart that our memorial halls and statues and tablets, the tattered flags of our regiments gathered in the Statehouses, are worth more to our young men by way of chastening and inspiration than the monuments of another hundred years of peaceful life could be.

But even if I am wrong, even if those who come after us are to forget all that we hold dear, and the future is to teach and kindle its children in ways as yet unrevealed, it is enough for us that this day is dear and sacred.

Accidents may call up the events of the war. You see a battery of guns go by at a trot, and for a moment you are back at White Oak Swamp, or Antietam, or on the Jerusalem Road. You hear a few shots fired in the distance, and for an instant your heart stops as you say to yourself, The skirmishers are at it, and listen for the long roll of fire from the main line. You meet an old comrade after many years of absence; he recalls the moment that you were nearly surrounded by the enemy, and again there comes up to you that swift and cunning thinking on which once hung life and freedom–Shall I stand the best chance if I try the pistol or the sabre on that man who means to stop me? Will he get his carbine free before I reach him, or can I kill him first?These and the thousand other events we have known are called up, I say, by accident, and, apart from accident, they lie forgotten.

But as surely as this day comes round we are in the presence of the dead. For one hour, twice a year at least–at the regimental dinner, where the ghosts sit at table more numerous than the living, and on this day when we decorate their graves–the dead come back and live with us.

I see them now, more than I can number, as once I saw them on this earth. They are the same bright figures, or their counterparts, that come also before your eyes; and when I speak of those who were my brothers, the same words describe yours.

I see a fair-haired lad, a lieutenant, and a captain on whom life had begun somewhat to tell, but still young, sitting by the long mess-table in camp before the regiment left the State, and wondering how many of those who gathered in our tent could hope to see the end of what was then beginning. For neither of them was that destiny reserved. I remember, as I awoke from my first long stupor in the hospital after the battle of Ball’s Bluff, I heard the doctor say, “He was a beautiful boy”, [Web note: Lt. William L. Putnam, 20th Mass.] and I knew that one of those two speakers was no more. The other, after passing through all the previous battles, went into Fredericksburg with strange premonition of the end, and there met his fate.[Web Note: Cpt. Charles F. Cabot, 20th Mass.]

I see another youthful lieutenant as I saw him in the Seven Days, when I looked down the line at Glendale. The officers were at the head of their companies. The advance was beginning. We caught each other’s eye and saluted. When next I looked, he was gone. [Web note: Lt. James. J. Lowell, 20th Mass.]

I see the brother of the last-the flame of genius and daring on his face–as he rode before us into the wood of Antietam, out of which came only dead and deadly wounded men. So, a little later, he rode to his death at the head of his cavalry in the Valley.

In the portraits of some of those who fell in the civil wars of England, Vandyke has fixed on canvas the type who stand before my memory. Young and gracious faces, somewhat remote and proud, but with a melancholy and sweet kindness. There is upon their faces the shadow of approaching fate, and the glory of generous acceptance of it. I may say of them , as I once heard it said of two Frenchmen, relics of the ancien regime, “They were very gentle. They cared nothing for their lives.” High breeding, romantic chivalry–we who have seen these men can never believe that the power of money or the enervation of pleasure has put an end to them. We know that life may still be lifted into poetry and lit with spiritual charm.

But the men, not less, perhaps even more, characteristic of New England, were the Puritans of our day. For the Puritan still lives in New England, thank God! and will live there so long as New England lives and keeps her old renown. New England is not dead yet. She still is mother of a race of conquerors–stern men, little given to the expression of their feelings, sometimes careless of their graces, but fertile, tenacious, and knowing only duty. Each of you, as I do, thinks of a hundred such that he has known.[Web note: Unfortunately for New England, no such “conquerors” have played for the Red Sox since 1918]. I see one–grandson of a hard rider of the Revolution and bearer of his historic name–who was with us at Fair Oaks, and afterwards for five days and nights in front of the enemy the only sleep that he would take was what he could snatch sitting erect in his uniform and resting his back against a hut. He fell at Gettysburg. [Web note: Col. Paul Revere, Jr., 20th Mass.].

His brother , a surgeon, [Web note: Edward H.R. Revere] who rode, as our surgeons so often did, wherever the troops would go, I saw kneeling in ministration to a wounded man just in rear of our line at Antietam, his horse’s bridle round his arm–the next moment his ministrations were ended. His senior associate survived all the wounds and perils of the war, but , not yet through with duty as he understood it, fell in helping the helpless poor who were dying of cholera in a Western city.

I see another quiet figure, of virtuous life and quiet ways, not much heard of until our left was turned at Petersburg. He was in command of the regiment as he saw our comrades driven in. He threw back our left wing, and the advancing tide of defeat was shattered against his iron wall. He saved an army corps from disaster, and then a round shot ended all for him. [Web note: Major Henry Patten, 20th Mass.]

There is one who on this day is always present on my mind. [Web note: Henry Abbott, 20th Mass.] He entered the army at nineteen, a second lieutenant. In the Wilderness, already at the head of his regiment, he fell, using the moment that was left him of life to give all of his little fortune to his soldiers.I saw him in camp, on the march, in action. I crossed debatable land with him when we were rejoining the Army together. I observed him in every kind of duty, and never in all the time I knew him did I see him fail to choose that alternative of conduct which was most disagreeable to himself. He was indeed a Puritan in all his virtues, without the Puritan austerity; for, when duty was at an end, he who had been the master and leader became the chosen companion in every pleasure that a man might honestly enjoy. His few surviving companions will never forget the awful spectacle of his advance alone with his company in the streets of redericksburg.[Web note: The legendary suicidal charge of the 20th Mass. Regiment occurred on Dec. 11, 1862.] In less than sixty seconds he would become the focus of a hidden and annihilating fire from a semicircle of houses. His first platoon had vanished under it in an instant, ten men falling dead by his side. He had quietly turned back to where the other half of his company was waiting, had given the order, “Second Platoon, forward!” and was again moving on, in obedience to superior command, to certain and useless death, when the order he was obeying was countermanded. The end was distant only a few seconds; but if you had seen him with his indifferent carriage, and sword swinging from his finger like a cane, you would never have suspected that he was doing more than conducting a company drill on the camp parade ground. He was little more than a boy, but the grizzled corps commanders knew and admired him; and for us, who not only admired, but loved, his death seemed to end a portion of our life also.

There is one grave and commanding presence that you all would recognize, for his life has become a part of our common history. [Web note: William Bartlett, 20th Mass.]. Who does not remember the leader of the assault of the mine at Petersburg? The solitary horseman in front of Port Hudson, whom a foeman worthy of him bade his soldiers spare, from love and admiration of such gallant bearing? Who does not still hear the echo of those eloquent lips after the war, teaching reconciliation and peace? I may not do more than allude to his death, fit ending of his life. All that the world has a right to know has been told by a beloved friend in a book wherein friendship has found no need to exaggerate facts that speak for themselves. I knew him ,and I may even say I knew him well; yet, until that book appeared, I had not known the governing motive of his soul. I had admired him as a hero. When I read, I learned to revere him as a saint. His strength was not in honor alone, but in religion; and those who do not share his creed must see that it was on the wings of religious faith that he mounted above even valiant deeds into an empyrean of ideal life.

I have spoken of some of the men who were near to me among others very near and dear, not because their lives have become historic, but because their lives are the type of what every soldier has known and seen in his own company. In the great democracy of self-devotion private and general stand side by side. Unmarshalled save by their own deeds, the army of the dead sweep before us, “wearing their wounds like stars.” It is not because the men I have mentioned were my friends that I have spoken of them, but, I repeat, because they are types. I speak of those whom I have seen. But you all have known such; you, too, remember!

It is not of the dead alone that we think on this day. There are those still living whose sex forbade them to offer their lives, but who gave instead their happiness. Which of us has not been lifted above himself by the sight of one of those lovely, lonely women, around whom the wand of sorrow has traced its excluding circle–set apart, even when surrounded by loving friends who would fain bring back joy to their lives? I think of one whom the poor of a great city know as their benefactress and friend. I think of one who has lived not less greatly in the midst of her children, to whom she has taught such lessons as may not be heard elsewhere from mortal lips. The story of these and her sisters we must pass in reverent silence. All that may be said has been said by one of their own sex —

But when the days of golden dreams had perished,

And even despair was powerless to destroy,

Then did I learn how existence could be cherished,

Strengthened, and fed without the aid of joy.

Then did I check the tears of useless passion,

weaned my young soul from yearning after thine

Sternly denied its burning wish to hasten

Down to that tomb already more than mine.

Comrades, some of the associations of this day are not only triumphant, but joyful. Not all of those with whom we once stood shoulder to shoulder–not all of those whom we once loved and revered–are gone. On this day we still meet our companions in the freezing winter bivouacs and in those dreadful summer marches where every faculty of the soul seemed to depart one after another, leaving only a dumb animal power to set the teeth and to persist– a blind belief that somewhere and at last there was bread and water. On this day, at least, we still meet and rejoice in the closest tie which is possible between men– a tie which suffering has made indissoluble for better, for worse.

When we meet thus, when we do honor to the dead in terms that must sometimes embrace the living, we do not deceive ourselves. We attribute no special merit to a man for having served when all were serving. We know that, if the armies of our war did anything worth remembering, the credit belongs not mainly to the individuals who did it, but to average human nature. We also know very well that we cannot live in associations with the past alone, and we admit that, if we would be worthy of the past, we must find new fields for action or thought, and make for ourselves new careers.

But, nevertheless, the generation that carried on the war has been set apart by its experience. Through our great good fortune, in our youth our hearts were touched with fire. It was given to us to learn at the outset that life is a profound and passionate thing. While we are permitted to scorn nothing but indifference, and do not pretend to undervalue the worldly rewards of ambition, we have seen with our own eyes, beyond and above the gold fields, the snowy heights of honor, and it is for us to bear the report to those who come after us. But, above all, we have learned that whether a man accepts from Fortune her spade, and will look downward and dig, or from Aspiration her axe and cord, and will scale the ice, the one and only success which it is his to command is to bring to his work a mighty heart.

Such hearts–ah me, how many!–were stilled twenty years ago; and to us who remain behind is left this day of memories. Every year–in the full tide of spring, at the height of the symphony of flowers and love and life–there comes a pause, and through the silence we hear the lonely pipe of death. Year after year lovers wandering under the apple trees and through the clover and deep grass are surprised with sudden tears as they see black veiled figures stealing through the morning to a soldier’s grave. Year after year the comrades of the dead follow, with public honor, procession and commemorative flags and funeral march — honor and grief from us who stand almost alone, and have seen the best and noblest of our generation pass away.

But grief is not the end of all. I seem to hear the funeral march become a paean. I see beyond the forest the moving banners of a hidden column. Our dead brothers still live for us, and bid us think of life, not death–of life to which in their youth they lent the passion and joy of the spring. As I listen , the great chorus of life and joy begins again, and amid the awful orchestra of seen and unseen powers and destinies of good and evil our trumpets sound once more a note of daring, hope, and will.

THE SOLDIER’S FAITH

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

An Address Delivered on Memorial Day, May 30, 1895, at a Meeting Called by the Graduating Class of Harvard University. President Theodore Roosevelt’s admiration for this speech was a factor in Holmes’ nomination to the US Supreme Court. The most quoted line of this speech is “We have shared the incommunicable experience of war; we have felt, we still feel, the passion of life to its top.”

Any day in Washington Street [in Boston], when the throng is greatest and busiest, you may see a blind man playing a flute. I suppose that some one hears him. Perhaps also my pipe may reach the heart of some passer in the crowd.

I once heard a man say, “Where Vanderbilt sits, there is the head of the table. I teach my son to be rich.” He said what many think. For although the generation born about 1840, and now governing the world, has fought two at least of the greatest wars in history, and has witnessed others, war is out of fashion, and the man who commands attention of his fellows is the man of wealth. Commerce is the great power. The aspirations of the world are those of commerce. Moralists and philosophers, following its lead, declare that war is wicked, foolish, and soon to disappear.

The society for which many philanthropists, labor reformers, and men of fashion unite in longing is one in which they may be comfortable and may shine without much trouble or any danger. The unfortunately growing hatred of the poor for the rich seems to me to rest on the belief that money is the main thing (a belief in which the poor have been encouraged by the rich), more than on any other grievance. Most of my hearers would rather that their daughters or their sisters should marry a son of one of the great rich families than a regular army officer, were he as beautiful, brave, and gifted as Sir William Napier. I have heard the question asked whether our war was worth fighting, after all. There are many, poor and rich, who think that love of country is an old wife’s tale, to be replaced by interest in a labor union, or, under the name of cosmopolitanism, by a rootless self-seeking search for a place where the most enjoyment may be had at the least cost.

Meantime we have learned the doctrine that evil means pain, and the revolt aginst pain in all its forms has grown more and more marked. From societies for the prevention of cruelty to animals up to socialism, we express in numberless ways the notion that suffering is a wrong which can be and ought to be prevented, and a whole literature of sympathy has sprung into being which points out in story and in verse how hard it is to be wounded in the battle of life, how terrible, how unjust it is that any one should fail.

Even science has had its part in the tendencies which we observe. It has shaken established religion in the minds of very many. It has pursued analysis until at last this thrilling world of colors and passions and sounds has seemed fatally to resolve itself into one vast network of vibrations endlessly weaving an aimless web, and the rainbow flush of cathedral windows, which once to enraptured eyes appeared the very smile of God, fades slowly out into the pale irony of the void.

And yet from vast orchestras still comes the music of mighty symphonies. Our painters even now are spreading along the walls of our Library glowing symbols of mysteries still real, and the hardly silenced cannon of the East proclaim once more that combat and pain still are the portion of man. For my own part, I believe that the struggle for life is the order of the world, at which it is vain to repine. I can imagine the burden changed in the way it is to be borne, but I cannot imagine that it ever will be lifted from men’s backs. I can imagine a future in which science shall have passed from the combative to the dogmatic stage, and shall have gained such catholic acceptance that it shall take control of life, and condemn at once with instant execution what now is left for nature to destroy. But we are far from such a future, and we cannot stop to amuse or to terrify ourselves with dreams. Now, at least, and perhaps as long as man dwells upon the globe, his destiny is battle, and he has to take the chances of war. If it is our business to fight, the book for the army is a war-song, not a hospital-sketch. It is not well for soldiers to think much about wounds. Sooner or later we shall fall; but meantime it is for us to fix our eyes upon the point to be stormed, and to get there if we can.

Behind every scheme to make the world over, lies the question, What kind of world do you want? The ideals of the past for men have been drawn from war, as those for women have been drawn from motherhood. For all our prophecies, I doubt if we are ready to give up our inheritance. Who is there who would not like to be thought a gentleman? Yet what has that name been built on but the soldier’s choice of honor rather than life? To be a soldier or descended from soldiers, in time of peace to be ready to give one’s life rather than suffer disgrace, that is what the word has meant; and if we try to claim it at less cost than a splendid carelessness for life, we are trying to steal the good will without the responsibilities of the place. We will not dispute about tastes. The man of the future may want something different. But who of us could endure a world, although cut up into five-acre lots, and having no man upon it who was not well fed and well housed, without the divine folly of honor, without the senseless passion for knowledge outreaching the flaming bounds of the possible, without ideals the essence of which is that they can never be achieved? I do not know what is true. I do not know the meaning of the universe. But in the midst of doubt, in the collapse of creeds, there is one thing I do not doubt, that no man who lives in the same world with most of us can doubt, and that is that the faith is true and adorable which leads a soldier to throw away his life in obedience to a blindly accepted duty, in a cause which he little understands, in a plan of campaign of which he has little notion, under tactics of which he does not see the use.

Most men who know battle know the cynic force with which the thoughts of common sense will assail them in times of stress; but they know that in their greatest moments faith has trampled those thoughts under foot. If you wait in line, suppose on Tremont Street Mall, ordered simply to wait and do nothing, and have watched the enemy bring their guns to bear upon you down a gentle slope like that of Beacon Street, have seen the puff of the firing, have felt the burst of the spherical case-shot as it came toward you, have heard and seen the shrieking fragments go tearing through your company, and have known that the next or the next shot carries your fate; if you have advanced in line and have seen ahead of you the spot you must pass where the rifle bullets are striking; if you have ridden at night at a walk toward the blue line of fire at the dead angle of Spottsylvania, where for twenty-four hours the soldiers were fighting on the two sides of an earthwork, and in the morning the dead and dying lay piled in a row six deep, and as you rode you heard the bullets splashing in the mud and earth about you; if you have been in the picket-line at night in a black and unknown wood, have heard the splat of the bullets upon the trees, and as you moved have felt your foot slip upon a dead man’s body; if you have had a blind fierce gallop against the enemy, with your blood up and a pace that left no time for fear –if, in short, as some, I hope many, who hear me, have known, you have known the vicissitudes of terror and triumph in war; you know that there is such a thing as the faith I spoke of. You know your own weakness and are modest; but you know that man has in him that unspeakable somewhat which makes him capable of miracle, able to lift himself by the might of his own soul, unaided, able to face anniliation for a blind belief.

From the beginning, to us, children of the North, life has seemed a place hung about by dark mists, out of which comes the pale shine of dragon’s scales and the cry of fighting men, and the sound of swords. Beowolf, Milton, Durer, Rembrandt, Schopenhauer, Turner, Tennyson, from the first war song of the race to the stall-fed poetry of modern English drawing rooms, all have had the same vision, and all have had a glimpse of a light to be followed. “The end of wordly life awaits us all. Let him who may, gain honor ere death. That is best for a warrior when he is dead.” So spoke Beowolf a thousand years ago.

Not of the sunlight,

Not of the moonlight,

Not of the starlight!

O Young Mariner,

Down to the haven.

Call your companions,

Launch your vessel,

And crowd your canvas.

And, ere it vanishes

Over the margin,

After it, follow it,

Follow the Gleam.

So sang Tennyson in the voice of the dying Merlin.

When I went to the war I thought that soldiers were old men. I remembered a picture of the revolutionary soldier which some of you may have seen, representing a white-haired man with his flint-lock slung across his back. I remembered one or two examples of revolutionary soldiers wom I have met, and I took no account of the lapse of time. It was not long after, in winter quarters, as I was listening to some of the sentimental songs in vogue, such as–

Farewell, Mother, you may never

See your darling boy again,

that it came over me that the army was made up of what I should now call very young men. I dare say that my illusion has been shared by some of those now present, as they have looked at us upon whose heads the white shadows have begun to fall. But the truth is that war is the business of youth and early middle age. You who called this assemblage together, not we, would be the soldiers of another war, if we should have one, and we speak to you as the dying Merlin did in the verse which I have just quoted. Would that the blind man’s pipe might be transformed by Merlin’s magic, to make you hear the bugles as once we heard them beneath the morning stars! For you it is that now is sung the Song of the Sword:–

The War-Thing, the Comrade,

Father of Honor,

And Giver of kingship,

The fame-smith, the song master.

Priest (saith the Lord)

Of his marriage with victory

…

Clear singing, clean slicing;

Sweet spoken, soft finishing;

Making death beautiful

Life but a coin

To be staked in a pastime

Whose playing is more

Than the transfer of being;

Arch-anarch, chief builder,

Prince and evangelist,

I am the Will of God:

I am the Sword.

War, when you are at it, is horrible and dull. It is only when time has passed that you see that its message was divine. I hope it may be long before we are called again to sit at that master’s feet. But some teacher of the kind we all need. In this snug, over-safe corner of the world we need it, that we may realize that our comfortable routine is no eternal necessity of things, but merely a little space of calm in the midst of the tempestuous untamed streaming of the world, and in order that we may be ready for danger. We need it in this time of individualist negations, with its literature of French and American humor, revolting at discipline, loving flesh-pots, and denying that anything is worthy of reverence–in order that we may remember all that buffoons forget. We need it everywhere and at all times. For high and dangerous action teaches us to believe as right beyond dispute things for which our doubting minds are slow to find words of proof. Out of heroism grows faith in the worth of heroism. The proof comes later, and even may never come. Therefore I rejoice at every dangerous sport which I see pursued. The students at Heidelberg, with their sword-slashed faces, inspire me with sincere respect. I gaze with delight upon our polo players. If once in a while in our rough riding a neck is broken, I regard it, not as a waste, but as a price well paid for the breeding of a race fit for headship and command.

We do not save our traditions, in our country. The regiments whose battle-flags were not large enough to hold the names of the battles they had fought vanished with the surrender of Lee, although their memories inherited would have made heroes for a century. It is the more necessary to learn the lesson afresh from perils newly sought, and perhaps it is not vain for us to tell the new generation what we learned in our day, and what we still believe. That the joy of life is living, is to put out all one’s powers as far as they will go; that the measure of power is obstacles overcome; to ride boldly at what is in front of you, be it fence or enemy; to pray, not for comfort, but for combat; to keep the soldier’s faith against the doubts of civil life, more besetting and harder to overcome than all the misgivings of the battlefield, and to remember that duty is not to be proved in the evil day, but then to be obeyed unquestioning; to love glory more than the temptations of wallowing ease, but to know that one’s final judge and only rival is oneself: with all our failures in act and thought, these things we learned from noble enemies in Virginia or Georgia or on the Mississippi, thirty years ago; these things we believe to be true.

“Life is not lost”, said she,

“for which is bought Endless renown.”

We learned also, and we still believe, that love of country is not yet an idle name.

Deare countrey! O how dearly deare

Ought thy rememberance, and perpetuall band

Be to thy foster child, that from thy hand

Did commun breath and nouriture receave!

How brutish is it not to understand

How much to her we owe, that all us gave;

That much to her we owe, that all us gave;

That gave unto us all, whatever good we have!

As for us, our days of combat are over. Our swords are rust. Our guns will thunder no more. The vultures that once wheeled over our heads must be buried with their prey. Whatever of glory must be won in the council or the closet, never again in the field. I do not repine. We have shared the incommunicable experience of war; we have felt, we still feel, the passion of life to its top.

Three years ago died the old colonel of my regiment, the Twentieth Massachusetts. [Web note: Col. William Raymond Lee] He gave the regiment its soul. No man could falter who heard his “Forward, Twentieth!” I went to his funeral. From a side door of the church a body of little choir- boys came in alike a flight of careless doves. At the same time the doors opened at the front, and up the main aisle advanced his coffin, followed by the few grey heads who stood for the men of the Twentieth, the rank and file whom he had loved, and whom he led for the last time. The church was empty. No one remembered the old man whom we were burying, no one save those next to him, and us. And I said to myself, The Twentieth has shrunk to a skeleton, a ghost, a memory, a forgotten name which we other old men alone keep in our hearts. And then I thought: It is right. It is as the colonel would have it. This also is part of the soldier’s faith: Having known great things, to be content with silence. Just then there fell into my hands a little song sung by a warlike people on the Danube, which seemed to me fit for a soldier’s last word, another song of the sword, but a song of the sword in its scabbard, a song of oblivion and peace.

A soldier has been buried on the battlefield.

And when the wind in the tree-tops roared,

The soldier asked from the deep dark grave:

“Did the banner flutter then?”

“Not so, my hero,” the wind replied.

“The fight is done, but the banner won,

Thy comrades of old have borne it hence,

Have borne it in triumph hence.”

Then the soldier spake from the deep dark grave:

“I am content.”

Then he heareth the lovers laughing pass,

and the soldier asks once more:

“Are these not the voices of them that love,

That love–and remember me?”

“Not so, my hero,” the lovers say,

“We are those that remember not;

For the spring has come and the earth has smiled,

And the dead must be forgot.”

Then the soldier spake from the deep dark grave:

“I am content.”

March 6, 1935

OBITUARY

Washington Holds Bright Memories of Justice Holmes’s Long and Useful Life

American Legend in Life of Holmes

Soldier, Jurist and Philosopher, He Sprang From New England’s Cultural Dominance

Rare Genius for the Law

‘A Deserving Fame Never Dimmed and Always Growing,’ Said Justice Hughes

By THE NEW YORK TIMES

The Associated Press

Oliver Wendell Holmes, 1931

s Justice Holmes grew old he became a figure for legend. Eager young students of history and the law, with no possibility of an introduction to him, made pilgrimages to Washington merely that they might remember at least the sight of him on the bench of the Supreme Court. Others so fortunate as to be invited to his home were apt to consider themselves thereafter as men set apart. Their elders, far from discouraging this attitude, strengthened it.

A group of leading jurists and liberals filled a volume of essays in praise of him, and on the occasion of its presentation Chief Justice Hughes said:

“The most beautiful and the rarest thing in the world is a complete human life, unmarred, unified by intelligent purpose and uninterrupted accomplishment, blessed by great talent employed in the worthiest activities, with a deserving fame never dimmed and always growing. Such a rarely beautiful life is that of Mr. Justice Holmes.”

Born in Boston in 1841

He was born on March 8, 1841, in Boston. The cultural dominance of New England was at its height. The West was raw, great parts of it wilderness as yet only sketchily explored. A majority of the nation’s citizens still considered the enslavement of Negroes as the operation of a law of God, and Darwin had not yet published his “Origin of Species.”

The circumstances of his birth were fortunate. His father, Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes, was of New England’s ruling caste and the atmosphere of his home was at once brahminical, scientific and literary. They boy was to start each day at that “autocratic” breakfast table where a bright saying won a child a second helping of marmalade.

The boy was prepared for Harvard by E. S. Dixwell of Cambridge. He was fortunate again in this. Well-tutored, he made an excellent record in college. His intimacy with Mr. Dixwell’s household was very close. His tutor’s daughter, Fanny Dixwell, and he fell in love with each other and later they were married.

Fort Sumter was fired on and President Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers. Young Holmes, 20 years old and shortly to be graduated from Harvard with the class of ’61, walked down Beacon Hill with an open Hobbe’s “Leviathan” in his hand and learned that he was commissioned in the Twentieth Massachusetts Volunteers.

The regiment, largely officered by young Harvard men and later to be known as the “Harvard Regiment,” was ordered South and into action at Ball’s Bluff. There were grave tactical errors and the Union troops were driven down the cliff on the Virginia shore and into the Potomac. Men trying to swim to safety were killed and wounded men were drowned.

Lieutenant Holmes, with a bullet through his breast, was placed in a boat with dying men and ferried through saving darkness to the Maryland shore.

His wound was serious, but the sufferer was young and storng. For convalescence he was returned to Boston. On his recovery he returned to the front.

At Antietam a bullet pierced his neck and again his condition was critical. Dr. Holmes, on learning the news, set out to search for his son. The search lasted many worried days and brought the father close to the lines at several points. He found his son already convalescent and brought him back to Boston, where he wrote his experiences under the title, “My Hunt for the Captain,” an article that was enthusiastically received as bringing home to Boston a first-hand picture of the trials of war directly behind the lines.

Wounded a Third Time

Back at the front, the young officer was again wounded. A bullet cut through tendons and lodged in his heel. This wound was long in healing and Holmes was retired to Boston with the brevet ranks of Colonel and Major.

The emergency of war over, his life was his own again. There was the question, then, of what to do with it. Writing appealed to him. He had been class poet and prize essayist in college. But he finally turned to law, although it was long before he was sure that he had taken the best course.

“It cost me some years of doubt and unhappiness,” he said later, “before I could say to myself: ‘The law is part of the universe–if the universe can be thought about, one part must reveal it as much as another to one who can see that part. It is only a question if you have the eyes.'”

Philosophy and William James helped him find his legal eyes while he studied in Harvard Law School and James, a year younger, was studying medicine. Through long nights they discussed their “dilapidated old friend the Kosmos.” James later was to write in affectionate reminiscence of “your whitely lit-up room, drinking in your profound wisdom, your golden jibes, your costly imagery, listening to your shuddering laughter.”

But while James went on, continuing in Germany his search for the meanings of the universe, Holmes decided that “maybe the universe is too great a swell to have a meaning,” that his task was to “make his own universe livable,” and he drove deep into the study of the law.

He took his LL. B. in 1866 and went to Europe to climb some mountains. Early in 1867 he was admitted to the bar and James noted that “Wendell is working too hard.” The hard work brought results. In 1870 he was made editor of the American Law Review.

Two years later, on June 17, 1872, he married Fanny Bowditch Dixwell and in March of the next year became a member of the law firm of Shattuck, Homes & Munroe, resigning his editorship but continuing to write articles for The Review. In that same year, 1873, his important edition of Kent’s Commentaries appeared.

His papers, particularly one on English equity, which bristled with citations in Latin and German, showed that he was a master scholar where mastery meant labor and penetration. It was into these early papers that he put the fundamentals of an exposition of the law that he was later to deliver in Lowell Lectures at Harvard and to publish under the title, “The Common Law.” In this book, to quote Benjamin N. Cardozo, he “packed a whole philosophy of legal method into a fragment of a paragraph.”

The part to which Judge Cardozo referred reads:

“The life of the law has not been logic; it has been experience. The felt necessities of the time, the prevalent moral and political theories, intuitions of public policy avowed or unconscious, even with the prejudices which judges share with their follow-men, have had a great deal more to do than the syllogism in determining the rules by which men should be governed. The law embodies the story of a nation’s development through many centuries, and it cannot be dealt with as if it contained only the axioms and corollaries of a book of mathematics.”

Judge Cardozo, commenting on this, wrote:

“The student of juristic method, bewildered in a maze of precedents, feels the thrill of a new apocalypse in the flash of this revealing insight. Here is the text to be unfolded. All that is to come will be development and commentary. Flashes there are like this in his earlier manner as in his latest, yet the flashes grow more frequent, the thunder peals more resonant, with the movement of the years.”

Makes His Debut as Judge

Holmes was only 39 years old when Harvard called him back to teach in her Law School and 41 when he became an Associate Justice on the Massachusetts Supreme Court bench.

So in that great period when Joseph H. Choate could call a Federal income tax “sheer communism,” the young Massachusetts justice could, with no bias, write dozens of dissenting opinions in which he expressed views that since have been molded into law.

He was Chief Justice on the Commonwealth bench when, in 1901, Theodore Roosevelt noted that Holmes’s “labor decisions” were criticized by “some of the big railroad men and other members of large corporations.” Oddly enough the successor of William McKinley thought that was “a strong point in Judge Holmes’s favor.”

In reference to this the President wrote to Henry Cabot Lodge:

“The ablest lawyers and greatest judges are men whose past has naturally brought them into close relationship with the wealthiest and most powerful clients and I am glad when I can find a judge who has been able to preserve his aloofness of mind so as to keep his broad humanity of feeling and his sympathy for the class from which he has not drawn clients.”

In further expression of this approval he in 1902 appointed Judge Holmes to the Supreme Court of the United States, an appointment that was confirmed by the Senate immediately and unanimously.

In a dissenting opinion written early in his career on the Supreme bench Justice Holmes bluntly told his associates that the case in hand had been decided by the majority on an economic theory which a large part of the country did not entertain, that general principles do not decide concrete cases, that the outcome depends on a judgment or institution more subtle than any articulate major premise.

A great struggle between the forces of Theodore Roosevelt and the elder J. P. Morgan began on March 10, 1902, when the government filed suit in the United States Circuit Court for the district of Minnesota charging that the Great Northern Securities Company was “a virtual consolidation of two competing transcontinental lines” whereby not only would “monopoly of the interstate and foreign commerce, formerly carried on by them as competitors, be created,” but, through use of the same machinery, “the entire railway systems of the country may be absorbed, merged, and consolidated.”

In April, 1903, the lower court decided for the government and 8,000 pages of records and briefs went to the United States Supreme Court for final review. On March 14, 1904, the high court found for the government, with Justice Holmes writing in dissent.

He held that the Sherman act did not prescribe the rule of “free competition among those engaged in interstate commerce,” as the majority held. It merely forbade “restraint of trade or commerce.” He asserted that the phrases “restraint of competition” and “restraint of trade” did not have the same meaning; that “restraint of trade,” which had “a definite and well-established significance in the common law, means and had always been understand to mean, a combination made by men engaged in a certain business for the purpose of keeping other men out of that business * * *.”

The objection to trusts was not the union of former competitors, but the sinister power exercised, or supposed to be exercised, by the combination in keeping rivals out of the business, he said. It was the ferocious extreme of competition with others, not the cessation of competition among the partners, which was the evil feared.

“Much trouble,” he continued, “is made by substituting other phrases, assumed to be equivalent, which are then argued from as if they were in the act. The court below argued as if maintaining competition were the express purpose of the act. The act says nothing about competition.”

It was at this time that John Morley visited America and returned to England with the affirmation that in Justice Homes America possessed the greatest judge of the English- speaking world. Time has reinforced the emphasis. In his years on the Supreme Court bench he had done more to mold the texture of the Constitution than any man since John Marshall revealed to the American people what their new Constitution might imply.

Matthew Arnold, in his essay on the study of poetry, says that the best way to separate the gold from the alloy in the coinage of the poets is by the test of a few lines carried in the thoughts.

Excerpts From Holmes’s Writings

From the opinions and other writings of Justice Holmes the following lines are some that might be used for this test:

“When men have realized that time has upset many fighting faiths, they may come to believe even more than they believe the very foundations of their own conduct that the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas–that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market, and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes can be carried out. That, at any rate, is the theory of our Constitution. It is an experiment, as all life is an experiment.”

“In the organic relations of modern society it may sometimes be hard to draw the line that is supposed to limit the authority of the Legislature to exercise or delegate the power of eminent domain. But to gather the streams from waste and to draw from them energy, labor without brains, and so to save mankind from toil that it can be spared, is to supply what, next to intellect, is the very foundation of all our achievements and all our welfare. If that purpose is not public, we should be at a loss to say what is.”

“The Fourteenth Amendment does not enact Mr. Herbert Spencer’s social statics.”

“While the courts must exercise a judgment of their own, it by no means is true that every law is void which may seem to the judges who pass upon it, excessive, unsuited to its ostensible end, or based upon conceptions of morality with which they disagree. Considerable latitude must be allowed for difference of view as well as for possible peculiar conditions which this court can know but imperfectly, if at all. Otherwise a Constitution, instead of embodying only relatively fundamental rules of right, as generally understood by all English-speaking communities, would become the partisan of a particular set of ethical or economic opinions, which by no means are held semper ubique et ab omnibus.”

His contribution to American life was not limited to the law. He lived as he advised others to live, in the “grand manner.” He sought quality rather than quantity of experience and knowledge of his success in living helped others to find it, too.

On his ninetieth birthday he delivered a short radio speech in reply to tributes from Chief Justice Hughes and other leaders of the American bar.

From a Latin poet he quoted the words:

“Death plucks my ears and says, ‘Live–I am coming.'”

And in one line he gave the core of a life philosophy:

“To live is to function; that is all there is to living.”

Left Bench Jan. 12, 1932

Justice Holmes resigned on Jan. 12, 1932. “The time has now come and I bow to the inevitable,” he wrote to the President. He left, amid national regret, almost thirty years after he had been appointed to the Supreme Court bench.

Soon after that, in a message to the Federal Bar Association, Justice Holmes wrote:

“I cannot say farewell to life and you in formal words. Life seems to me like a Japanese picture which our imagination does not allow to end with the margin. We aim at the infinite, and when our arrow falls to earth it is in flames.

“At times the ambitious ends of life have made it seem to me lonely, but it has not been. You have given me the companionship of dear friends who have helped to keep alive the fire in my heart. If I could think that I had sent a spark to those who come after, I should be ready to say good-bye.”

Justice Holmes was an honorary member of the Honourable Society of Lincoln’s Inn, London, to which also belonged such men as Oliver Cromwell, William Pitt, Benjamin Disraeli and William Ewart Gladstone.

Soon after retiring, his salary was cut in two by reason of the economy law. It was restored to $20,000 a year a few months later, however, by special action of the Senate.

In the Fall of 1931 appeared the “Representative Opinions of Mr. Justice Holmes.”

Mrs. Holmes died on April 30, 1929.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard