WASHINGTON YESTERDAY:

Afghan war planners operate in shadow of Civil War quartermaster

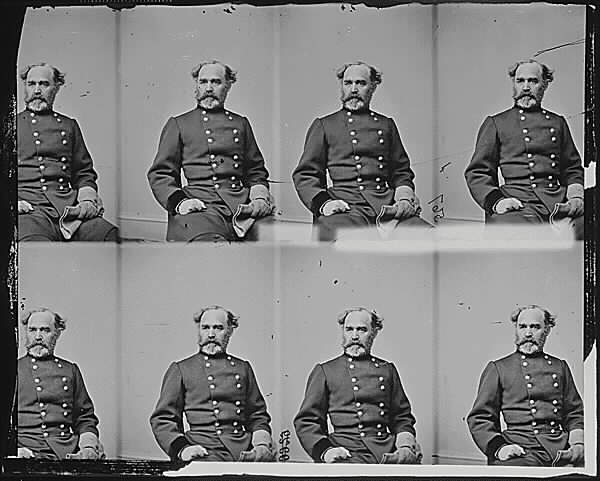

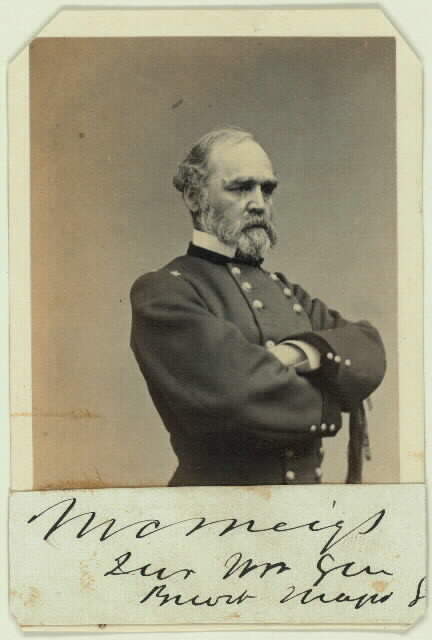

18 February 2002

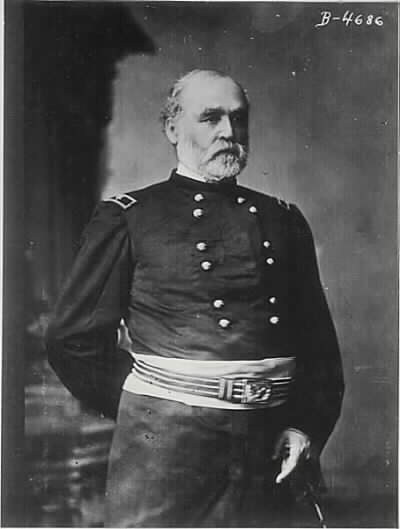

The military planners supplying America’s Afghan War with troops and arms probably haven’t spared a thought for the Civil War career of Montgomery C. Meigs. But they are operating in his shadow.

As the Union Army’s quartermaster general, dispatching men and equipment to the scattered battlefields of the war, Meigs was one of the few Union generals who proved his competence from beginning to end.

Some said the war could not have been won without him.

His intensity was fueled by a growing hatred of the Confederacy, an emotion that led him to place Arlington National Cemetery on the Virginia estate of the South’s leading general, Robert E. Lee.

Meigs saw to the army’s equipment and supplies as the force expanded from about 16,000 men to more than 700,000 in the first year alone. His office moved and housed the troops and supplied the guns and gear needed for battlefield success, all the while swatting at dishonest contractors and purveyors of shoddy goods.

Streams of uniforms, knapsacks, blankets, tents, rifles, cannon, ammunition, horses, wagons, tents, pontoon bridges, food and gear of every description flowed to the fighting armies. Railroads, ocean ships, river boats and horse-drawn wagons got it where it was needed.

Altogether, Meigs signed contracts worth $1.5 billion — an immense sum in the 1860s.

“Perhaps in the history of the world there was never so large an amount of money disbursed upon the order of a single man,” said Secretary of State William Seward.

“Without the services of this eminent soldier, the national cause must have been lost or deeply imperiled.”

Over a long career as a military engineer Meigs had already built the stone aqueduct that provided Washington with pure water and supervised construction of the Capitol’s cast-iron dome. He had served with leaders

on both sides of the national conflict, a roster including Lee and Confederate President Jefferson Davis who had been U.S. Secretary of War.

“The country is in a flame,” Meigs told his diary in May 1861 in the opening days of the war.

In something of a flame himself, the 44-year-old captain planned and helped execute a secret expedition which successfully relieved Fort Pickens in Florida, keeping it in Union hands.

Impressed, Lincoln put him to work organizing the efficient supply and logistics system a vastly increased army would need.

But Meigs had diplomatic talents as well.

In 1862, when Gen. George McClellan, the commander of the Army of the Potomac, became ill and petulantly refused to tell the White House his plans for engaging the enemy, a despairing Lincoln turned to Meigs.

Meigs advised Lincoln to consult directly with McClellan’s division commanders, a move which promptly brought the jealous and ego-driven general back to health and back to duty.

Author Joseph E. Stevens, writing in the April issue of “American History” magazine, said the incident led Lincoln to make Meigs one of his principal military advisers.

Meigs’ “tough-minded optimism — his understanding of the north’s overwhelming superiority in manpower and resources — helped dispel the gloom that often afflicted the president,” Stevens wrote.

As the war dragged on Meigs became increasingly bitter against the Confederate leaders he blamed for dividing the nation and plunging it into war. When an opportunity for revenge arose he took it.

By June 1864, the long list of war dead had created the need for a national cemetery. Meigs found the land for it at the Arlington, Va., estate and mansion of his Confederate nemesis, Robert E. Lee.

The general ordered 26 of the Union dead taken from an Army morgue and buried at Lee’s doorstep in what became Arlington National Cemetery.

Stevens writes that Meigs looked on with “grim satisfaction” as they were buried on Lee’s land. Meigs himself would be interred there in a grave near that of his son, killed in action by Confederate soldiers.

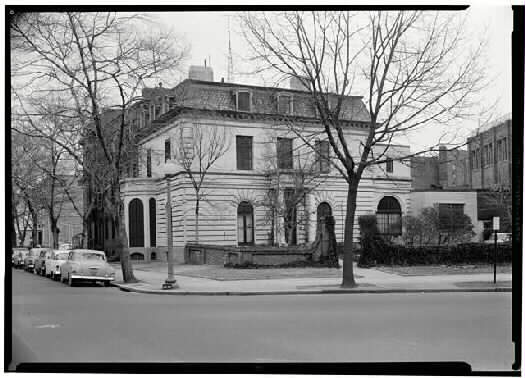

Resuming his engineering career years after the war, Meigs built the enormous red-brick Pension Building, now the National Building Museum. He turned its artistic embellishments into a tribute to Union veterans and his own wartime service.

Meigs banded the building with a 1,200-foot frieze along which terra-cotta soldiers march, sailors tug at their oars, and horse-drawn supply wagons lumber toward the front.

Looking up at the long band of soldiers one thing is clear. The former quartermaster general made sure they were all well armed and equipped.

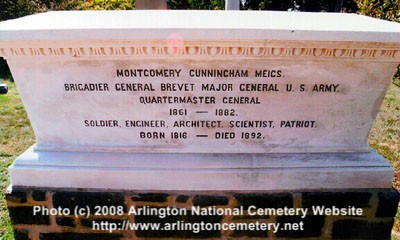

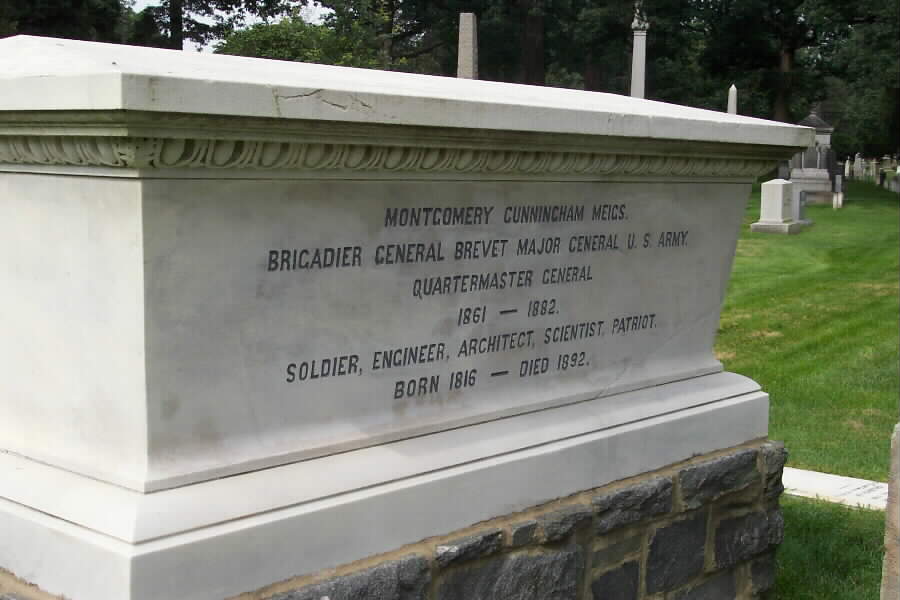

Meigs, Montgomery Cunningham (May 3, 1816 – Jan. 2, 1892), soldier and engineer, was born in Augusta, Georgia, the son of Dr. Charles Delucena Meigs and of Mary (Montgomery) Meigs of Philadelphia. He was an elder brother of John Forsyth Meigs. During his childhood the family moved from Georgia to Philadelphia, where he matriculated at the University of Pennsylvania in 1831. He later entered the United States Military Academy, graduating in 1836, fifth in his class. After temporary assignment to the artillery, he was transferred to the engineer corps of the Army, and thereafter, for a quarter of a century, his conspicuous ability was devoted to many important engineering projects. Of these, his favorite was the Washington Aqueduct, carrying a large part of the water supply from the Great Falls of the Potomac to the city of Washington. This work, of which he was in charge from November 1852 to September 1860, involved not only the devising of ingenious methods of controlling the flow and distribution of the water, but also the design of the monumental bridge across Cabin John Branch which for some fifty years remained unsurpassed as the longest masonry arch in the world. To this task was added from 1853 to 1859 the supervision of the building of the wings and dome of the national Capitol, and from 1855 to 1859, of the extension of the General Post Office building, as well as the direction of many minor works of construction.

In the fall of 1860, as a result of a disagreement over certain contracts, Meigs “incurred the ill will of the Secretary of War, John B. Floyd,” and was “banished to Tortugas in the Gulf of Mexico to construct fortifications at that place and at Key West”. Upon the resignation of Floyd a few months later, however, he was recalled to his work on the aqueduct at Washington.

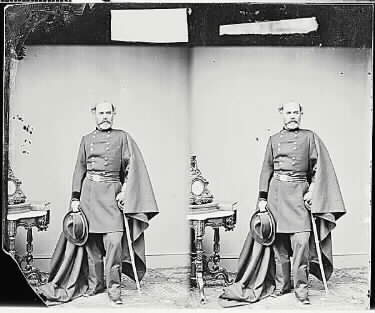

Here, in the critical days preceding the actual outbreak of the Civil War, Meigs and Lieutenant Colonel E. D. Keyes were quietly charged by President Lincoln and Secretary Seward with drawing up a plan for the relief of Fort Pickens, Florida, by means of a secret expedition; and in April 1861, together with Lieutenant D. D. Porter of the Navy, they carried out the expedition, embarking under orders from the President without the knowledge of either the Secretary of the Navy or the Secretary of War.

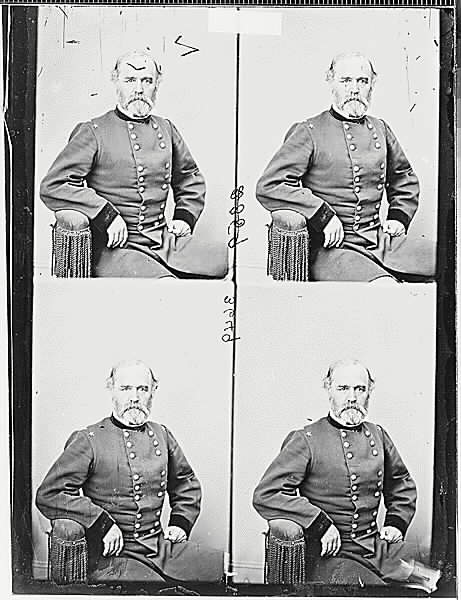

On May 14, 1861, Meigs was appointed Colonel, 11th Infantry, and on the following day, promoted to Brigadier General, he became Quartermaster General of the Army, in which capacity he served throughout the war. Of his work in this office James G. Blaine remarked: “Montgomery C. Meigs, one of the ablest graduates of the Military Academy, was kept from the command of troops by the inestimably important services he performed as Quartermaster-General. . . . Perhaps in the military history of the world there was never so large an amount of money disbursed upon the order of a single man. . . . The aggregate sum could not have been less during the war than fifteen hundred millions of dollars, accurately vouched and accounted for to the last cent.”. William H. Seward’s estimate was “that without the services of this eminent soldier the national cause must have been lost or deeply imperilled” (letter, May 28, 1867, from the Secretary of State, asking the good offices of diplomatic officers for General Meigs during a tour of Europe; in possession of the family).

His brilliant services during the hostilities included command of Grant’s base of supplies at Fredericksburg and Belle Plain (1864), command of a division of War Department employes in the defenses of Washington at the time of Early’s raid (July 11-14, 1864), personally supervising the refitting and supplying of Sherman’s army at Savannah (Januart 5-29, 1865), and at Goldsboro and Raleigh, North Carolina, reopening Sherman’s lines of supply (March-April 1865). He was brevetted Major General July 5, 1864.

As quartermaster-general after the Civil War, Meigs supervised plans for the new War Department building (1866-67), the National Museum (1876), the extension of the Washington Aqueduct (1876), and for a hall of records (1878). In 1867-68, to recuperate from the strain of his war service, he visited Europe, and in 1875-76 made another visit to study the government of European armies.

After his retirement on February 6, 1882, he became architect of the Pension Office building. He was a regent of the Smithsonian Institution, a member of the American Philosophical Society, and one of the earliest members of the National Academy of Sciences. In 1888, although he “was not a literary person and had no taste for writing except of official reports of work done,” at the request of the editors of Battles and Leaders of the Civil War he submitted an article on the relations of Lincoln and Seward to the military commanders during the war which was apparently intended as a reply to some of the statements in McClellan’s Own Story (1887). It was not printed, however, until long after the author’s death, when it appeared as a “document” in the American Historical Review (January 1921).

Meigs died in Washington after a short illness and his body was interred with high military honors in the National Cemetery at Arlington. The General Orders (January 4, 1892) issued at the time of his death declared that “the Army has rarely possessed an officer . . . who was entrusted by the government with a greater variety of weighty responsibilities, or who proved himself more worthy of confidence.”

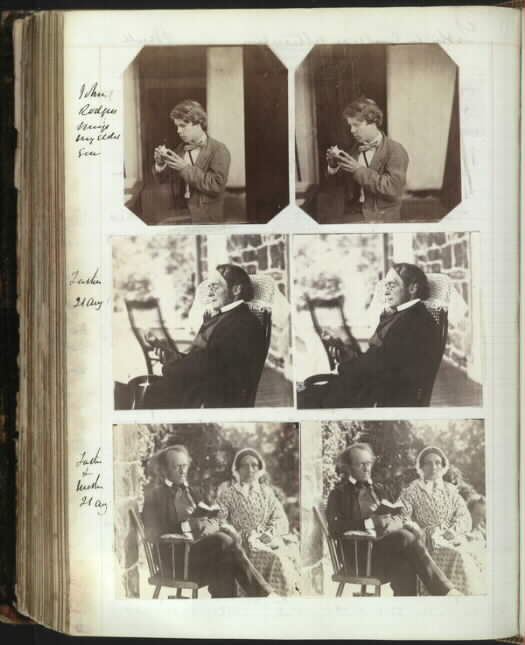

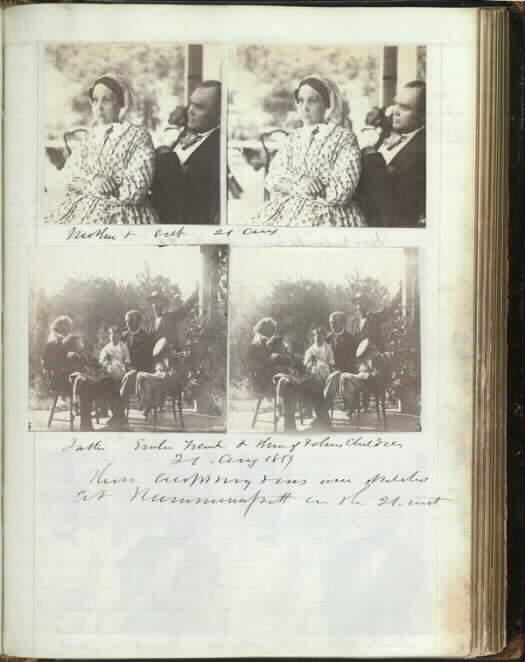

In 1841 he had married Louisa Rodgers, daughter of Commodore John Rodgers, 1773-1838. Four of their seven children lived to maturity, but one of these, John Rodgers Meigs, a Lieutenant of engineers, was killed in action during the Civil War.

Major General Montgomery Cunningham Meigs was the premier engineering officer of his times. He graduated from West Point and was immediately assigned to the Engineer Corps. He completed many projects in his lifetime, including the completion of the Capitol Dome in Washington, the Washington Aqueduct and the defenses of Washington, DC. He also designed and supervised the building of the Old Pension Building in Washington which is a National Historic Site.

A tribute contained in General Orders dated January 4, 1892, was perhaps his highest accolade: “The Army has rarely possessed an officer who was entrusted by the government with a greater variety of weighty responsibilities, or who proved himself more worthy of confidence.”

During the Civil War he served as Quartermaster General of the US Army and in this role provided huge quantities of materials to the victorious Union Army. In his capacity as Quartermaster General he recommended to the Secretary of War the seizure of the Arlington property as a military burial ground. Based on this recommendation, Arlington National Cemetery was originated in 1864. In that same year, his son, First Lieutenant John Rodgers Meigs, also a West Point graduate, was killed by Confederate partisans in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. His body was recovered and returned to Washington where it was interred in the Officer’s Section (Section One) of Arlington Cemetery. Today the younger Meigs’ gravestone, depicting him lying dead in the road – his pistol by his side – can be viewed among those of his parents and other members of the family. Yet another sad reminder of the cost of war.

Surprisingly, there are several connections between two of the most well-known sites in Washington, D.C.: the Smithsonian Institution and Arlington Cemetery. The most important of these is engineer Montgomery Meigs.

Montgomery Meigs’ involvement with the Smithsonian began in 1876 when he designed a preliminary plan for the new National Museum building. He later assisted architects Adolph Cluss and Carl Schulze with the development of the roof truss system for the new structure, now known as the Arts and Industries Building. Meigs was appointed a member of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian on December 26, 1885 and served until his term expired in December 1891. Meigs’ career culminated with perhaps his greatest structure, the Pension Building, erected between 1882-1887.

Meigs’ involvement with Arlington Cemetery can be traced back to June 1837. Fresh out of the United States Military Academy at West Point, Second Lieutenant Meigs accompanied First Lieutenant Robert E. Lee on a mission to survey the Mississippi River. Meigs and Lee had several commonalties: they were both from the South, Lee a Virginian and Meigs a Georgian; they were both West Point graduates; officers in the United States Army; and engineers . Lee and Meigs surveyed the river from Iowa to St. Louis. Together they devised a plan to render the Des Moines Rapids and the Rock River Rapids navigable. Their aim was to alter the flow of the river to save the harbor of St. Louis. The two men worked together from June 1837 to December when Lee returned to his beloved home, Arlington House, across the Potomac from Washington, D.C. . When war was declared between the northern and southern states in April 1861, Robert E. Lee resigned his commission from the United States Army and moved to Richmond, Virginia, leaving his wife Mary behind at Arlington House. Soon after, it became evident that the Union Army was going to cross the Potomac and Mary Lee vacated Arlington House. On May 24, 1861, Union troops occupied the house and military installations were built on the 1,100 acre estate.

In the same year, Joseph E. Johnston resigned as Quartermaster General of the United States Army to join Robert E. Lee in the Confederate cause. Montgomery C. Meigs was Johnston’s replacement. Meigs’ duties as Quartermaster General included oversight of government land use for military purposes and construction of all military and transportation facilities.

Historians have always believed that the primary reason for the selection of Arlington for a cemetery was an act of revenge carried out by Montgomery Meigs against his old colleague in arms Robert E .Lee for his allegiance to the Confederacy. Meigs’ own family had been divided by the war, for his brother elected to fight for the Confederacy. On November 19, 1863, Abraham Lincoln dedicated the first National Cemetery for the dead of the north on the Gettysburg Battlefield. Casualties only increased as the war continued, and in 1864 the Federal government decreed that additional burial grounds must be found for the dead. Montgomery Meigs was tasked with finding suitable land. Meigs wrote to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton suggesting that Robert E. Lee’s estate Arlington, which had been confiscated by the Federal government, be used for a military cemetery. “The grounds about the mansion are admirably adapted to such a use,” Meigs wrote on 15 June 1864. That same day, Stanton informed Meigs that he would allot 200 acres of the estate as burial ground.

In August 1864, twenty-six men were buried around Mrs. Lee’s rose garden. By the end of the war, 16,000 dead were buried near Arlington House, including 2,111 unknown soldiers buried in a mass grave in the “Tomb of the Unknown Dead from the Civil War.” Meigs’ involvement with the cemetery continued with his design of cast-iron headstones coated with zinc, similar in style to the original whitewashed wood headstones. Although Meigs’ design was not adapted, one Meigs headstone exists today in Section 13 of the cemetery.

The Confederacy and Arlington House were both lost to Robert E. Lee. With the grounds near the house used as a cemetery, there was no way the Lees would, or could, ever return to their home to live, and it was only from a distance during separate visits to Washington after the war that the Lees saw their home for the last time. Shortly after Robert E. Lee’s death in 1870, his eldest son Custis filed suit claiming that the confiscation of the estate during the Civil War was unconstitutional. After years of complicated legal proceedings, Lee won and ceded the title of the estate to the United States government for $150,000 in 1883 . Arlington was now an official national cemetery.

Meigs died in 1892, and was buried in Section One of Arlington Cemetery, less than one hundred feet from Mrs. Lee’s rose garden. Meigs’ grandfather, wife, Uncle and son are buried with him, the latter memorialized by a reclining statue showing the young man as he died fighting for the Union Army near Harrisonburg, Virginia in October 1864. The remains of Meigs’ grandfather were moved from Congressional Cemetery to join his grandson. His grave is marked with the original tombstone from Congressional Cemetery.

As you drive through the 612 acres which comprise Arlington Cemetery today, you see a massive stone gateway standing somewhat forlornly in the middle of a road which divides the many rows of white headstones. Something about its appearance seems familiar: the gate appears to be constructed of the same material as the Smithsonian Institution Building, Seneca sandstone.

Several different stone types were considered for the Smithsonian Building. A Building Committee was formed in February 1847, led by Robert Dale Owen, a Congressman from Indiana, to select the construction material for the Smithsonian Building. Several different stone types were investigated, including Aquia Creek freestone, used in several government buildings. Owen visited the Seneca sandstone quarries in March. He reported that the dark red stone “is comparatively soft, working freely before the chisel and hammer, and can even be cut with a knife; by exposure, it gradually indurates, and ultimately acquires a toughness and consistency that not only enables it to resist atmospheric vicissitudes, but even the most severe mechanical wear and tear.” Owen was sufficiently impressed with the Seneca stone that the Building Committee selected it as the material for the Castle Building in March 1847.

In 1870, Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs recommended to Secretary of War William W. Belknap that a gate be erected to denote the entrance to Arlington Cemetery. The 1870 Report of the Quartermaster General to the Secretary of War states, “The adoption of a handsome arched gateway of sandstone with iron gate, has been recommended. It is intended to build this gateway, which is to have plain Doric columns and rustic piers, with an arch of ten feet, at five of the largest and most visited cemeteries. The first one will be built at Arlington, Virginia; the others will probably be erected at Fredericksburg, Virginia, Marietta, Georgia, Nashville, Tennessee and Vicksburg, Mississippi.”

Irish-born architect Lot Flannery was selected to design the gates in 1871. Flannery selected Seneca sandstone. The Quartermaster General’s Report for 1871 states that “the work therein is progressing but slowly, owing to the difficulty of obtaining suitable stone from the quarry.” This lack of stone may be why the gate was not completed until 1880, five years before its namesake, General George B. McClellan, died.

The gate was erected as a tribute to General George B. McClellan who used Arlington House during the winter of 1861-1862 as headquarters during his command of the Army of the Potomac. The name MCCLELLAN is carved at the top of the gate with the inscription “Here Rest 15,585 of the 515,555 citizens Who Died in Defense of Our Country 1861 to 1865.” Quotations from Theodore O’Hara’s poem “Bivouac of the Dead” are inscribed on each side of the gate. Meigs’ presence is also noted here, for the name MEIGS is carved on the left column. McClellan, it is interesting to note, is not buried in Arlington, but is interred in Riverview Cemetery, Trenton, New Jersey.

Today similar gates exist in the national cemeteries of Marietta and Nashville. These gates are not made of Seneca sandstone but of gray granite. The McClellan Gate is a tribute not only to its namesake, but also to Seneca sandstone, indigenous to the Washington area. Due to overuse in the 19th century, the quarry of Seneca sandstone is now protected by the National Park Service in Poolesville, Maryland.

Montgomery Cunningham Meigs was born on 3 May 1816 in Augusta, Georgia, the son of Charles Delucena Meigs (19 February 1792-22 June 1869, buried in Hamanassett County, Pennsylvania), and Mary Montgomery Meigs (14 December 1794-13 May 1865). Died at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

His siblings were Charles Delucena Meigs, Jr., John Forsyth Meigs, Henry Vincent Meigs, Emily Skinner Meigs, William Montgomery Meigs, Samuel Emlen Meigs , Franklin Bache Meigs, Mary Crathorne Meigs.

MEIGS, CHARLES D

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: Unknown

- DATE OF DEATH: 09/03/1853

- DATE OF INTERMENT: Unknown

- BURIED AT: SITE 1

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

MEIGS, JOHN RODGERS

- BVT MAJOR US CORPS ENGRS

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: Unknown

- DATE OF DEATH: 10/03/1864

- DATE OF INTERMENT: Unknown

- BURIED AT: SITE 1

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

MEIGS, JOSIAH

- 1ST COMM GEN LAND OFC

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: Unknown

- DATE OF DEATH: 09/04/1822

- DATE OF INTERMENT: Unknown

- BURIED AT: SITE 1

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Charles DeLucena Meigs

Meigs Daughter

John Rodgers Meigs

Josiah Meigs

Louisa Rodgers Meigs

Samuel William Meigs

Vincent Trowbridge Meigs

Lieutenant Colonel Montgomery C. Meigs

Lieutenant Colonel Montgomery C. Meigs was given command of the 23rd Tank Battalion, 12th Armored Division four years after his graduation from West Point. His career is a record of intelligence and gallantry. His father being a naval officer, moved many times in his youth and attended some eight schools in different places prior to entering West Point.He declined a principal appointment to the Naval Academy in order to wait for an uncertain later appointment to West Point. During the later part of his school career he was handicapped by a painful back injury which kept him in a plaster cast for six months and in an iron brace for a year. Neverless he entered West Point when barely seventeen and graduated 44th in his class.

He chose the Cavalry as his branch of the Army and first served in the 8th Cavalry at Fort Bliss. In 1941 he was transferred to the 2nd Armored Divisin and in 1942 to the 7th Armored Division. While in these two divisions he was seriously and painfully injuredin motorcycle accidents, first with a broken neck vertebra and second with a broken knee.

Given command of the 23rd Tank Battalion of the 12th Armored Division after his second discharge from the hospital, he went overseas a year later, in the early autumn of 1944. The battalion went combat for the first time on December 9, in Alsace, against the Maginot Line. Throughout that day,Meigs,himself continually exposed to heavy mortar and artillery fire, directed the firing and movement of the battalion on a direct fire mission from the flank against the village of Binning, to support a reinforced infantry battalion which was assaulting frontally. The infantry occupied Binning in the afternoon. Meigs spent the night drawing up his plans and orders for an assault next morning on a sector of the Maginot Line just north of Rohrbach. December 10th the battalion was in action and under heavy fire for nine hours. The battalion took its objective, but was then met by well-concealed anti-tank fire. The battalion’s position was consolidated, preparatory to another attack next day. Again Meigs spent the night, his second without sleep, on his plans and orders. On the morning of December 11th, Meigs, with the lead tanks of his first assault wave got onto a ridge which the Germans had “zeroed in” with 88’s,well-concealed. Three tanks were hit and disabled. Meigs gave the order to hold up and locate the Germangun position. He proceeded in the direction of Bettwiller, soon picked up a gun flash, ordered smoke fired on the edge of the village and ordered the tanks to take cover. Immediately afterwards his own tank was hit in the turret by an 88 round and he was instantly killed.

He was posthumously awarded the Silver Star for “gallantry and extraordinary service”. His citation states that “Lieutenant Colonel Meigs’ actions during the three days’ operations under artillery, mortar, and small arms fire set an example for all officers and men of his battalion, inspiring them to continue the attack on the Division objective, which was taken on December 12, 1944.Lieutenant Colonel Meigs courage and utter disregard for his own life in leading his battalion, exemplifies the finest traditions of the Armed Forces of the United States”.

Montgomery C. Meigs

- Lieutenant Colonel, U.S. Army

- O-022930

- 23rd Tank Battalion, 12th Armored Division

- Entered the Service from: Maryland

- Died: December 11, 1944

- Buried at: Plot C Row 23 Grave 36

- Lorraine American Cemetery

- St. Avold, France

- Awards: Silver Star, Purple Heart

NOTE: J. Forsyth Meigs(born in 1820) was the brother of Montgomery Cummingham Meigs. Colonel Meigs’ father was named John Forsyth Meigs. Still searching for a valid connection to General Meigs.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard