Benjamin O. Davis Jr., 89, Dies; First Black General in Air Force

Saturday, July 6, 2002

Benjamin O. Davis Jr., 89, a pioneering military officer who was the leader of the fabled Tuskegee Airmen during World War II and the first African American to become a General in the Air Force, died July 4, 2002, at Walter Reed Army Medical Center. He had Alzheimer’s disease.

In a career that began in the days of segregation, General Davis, who was born in Washington and lived here for much of his life, compiled a long history of achievements and accomplishments. His combat record and that of the unit he led have been credited with playing a major role in prompting the integration of the armed services after World War II.

In 1970, after retiring from the Air Force, he supervised the federal sky marshal program that was designed to quell a rash of airliner hijackings. In 1971, he was named an assistant secretary of transportation.

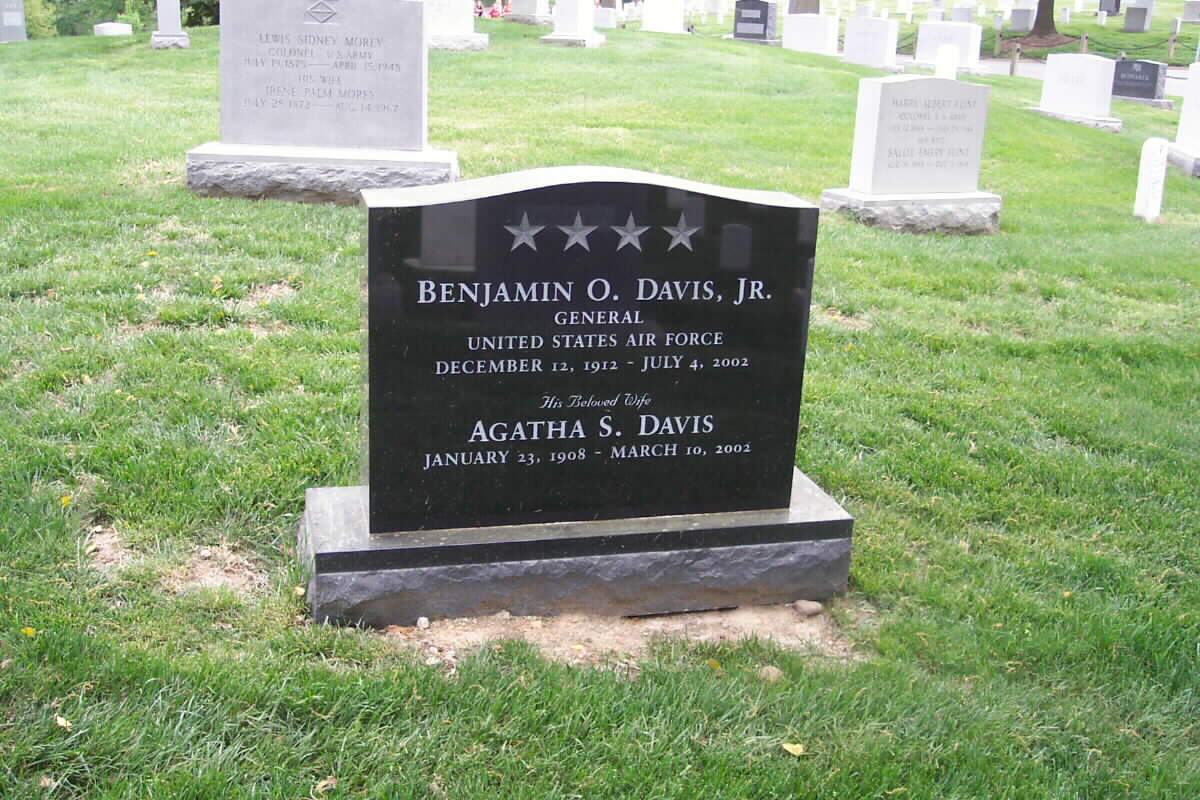

At the time he left the Air Force as a Lieutenant General, wearing three stars, he was the senior black officer in the armed forces. In 1998, President Bill Clinton awarded General Davis his fourth star, advancing him to full general.

“General Davis is here today as living proof that a person can overcome adversity and discrimination, achieve great things, turn skeptics into believers; and through example and perseverance, one person can bring truly extraordinary change,” Clinton said.

As the World War II commander of the 332nd Fighter Group, General Davis and his pilots escorted bombers on 200 air combat missions over Europe, flying into the teeth of some of the Nazi Luftwaffe’s most tenacious defenses.

It was one of the 332nd’s proudest achievements that not one of the bombers it protected was lost to an enemy fighter.

This dazzling success was a tribute both to the pilots’ skill and to General Davis’s ability as a commander, according to historian Alan Gropman.

General Davis was a natural leader, a stern disciplinarian and an officer with a clear idea of what his mission was and of the tactics required to carry it out, said Gropman, an author and chairman of the Department of Grand Strategy and Mobilization at the Industrial College of the Armed Forces.

Other escort units, according to Gropman, ranged widely to search out enemy fighters. Gen. Davis “told his men to stay with the bombers” that they were assigned to protect. “They were not out looking for glory. They were out to do their mission.”

General Davis flew 60 missions in the cockpit of P-39, P-40, P-47 and P-51 fighters. He won the Silver Star.

By the time he was assigned to lead the all-black unit, named the Tuskegee Airmen for the Alabama base at which they had trained, General Davis had withstood stern tests of his character, self-discipline and determination.

When General Davis graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, in 1936, he was only the fourth African American ever to do so.

At the academy, General Davis was shunned. Other cadets refused to speak with him except for official reasons. General Davis had no roommate in the dormitory and no one else assigned to his tent in the field, and he ate his meals without a word.

General Davis was born in Washington and graduated from high school in Cleveland. His father, Benjamin O. Davis Sr., was one of two black combat officers in the Army and eventually was promoted to Brigadier General.

When Benjamin Jr. was a teenager, his father paid a barnstorming pilot to give him an airplane ride. His son decided that he wanted to become a pilot and to attend West Point. There, he refused to give in to the harassment, Gropman said.

“I wasn’t leaving,” General Davis told Gropman. “This is something I wanted to do, and I wasn’t going to let anybody drive me out.”

After graduation, there was no was no black aviation unit for General Davis to join. He took other assignments in the Army until President Franklin D. Roosevelt decided in 1940 to create an African American squadron in the Army Air Corps. General Davis was chosen for command.

He earned his wings in 1942 and was sent the next year to North Africa to lead the 99th Fighter Squadron.

General Davis had long resented and opposed segregation. But as leader of the Tuskegee Airmen, he insisted that those under him refrain from demonstrating against its injustices. Instead, according to Gropman, he took the position that there was a war to be won and that the time to protest would come afterward. “He always believed in integration,” Gropman said.

In 1947, the Air Force was made a separate service. One of its generals conducted a study of segregation in the service and recommended integration. According to Gropman, a principal argument for it was the record of Davis and his pilots in proving that blacks could perform as well as whites in all jobs. The Air Force integrated in 1949.

General Davis did not believe that this solved all the nation’s racial problems. “I have felt prejudice all my life up to right now,” he told students at an Arlington elementary school 10 years ago. “Lots of improvement can be made in this nation, and you are the ones who can do it.”

Davis held a variety of increasingly responsible posts in the integrated Air Force, and retired as deputy commander in chief of U.S. Strike Command.

He retired from government in 1975 and lived for many years in Arlington before moving to a nursing home in Northwest. His autobiography was published by Smithsonian Institution Press in 1991.

His wife, Agatha, died this year. Survivors include a sister.

July 6, 2002

Air Force General Davis Dies

WASHINGTON – Benjamin O. Davis Jr., the leader of the famed all-black Tuskegee Airmen during World War II and the first black General in the Air Force, has died.

Davis, who was 89 and suffered from Alzheimer’s disease, died Thursday, July 4, 2002, at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington.

Davis, a native of Washington, began his military career during the era of segregation and led a unit of airmen that was credited with a major role in bringing about the integration of the armed services in the years after the war.

He was a 1936 graduate of the U.S. Military Academy and son of Benjamin O. Davis Sr., who rose to Brigadier General in the Army.

In 1970, after he retired from the Air Force, Davis was put in charge of the federal sky marshal program designed to stop airliner hijackings. The following year, he was named an Assistant Secretary of Transportation.

Davis left the Air Force as a Lieutenant General with three stars and was the senior black officer in the armed forces. President Clinton advanced Davis to a full General in 1998, awarding him a fourth star.

As commander of the 332nd Fighter Group, Davis and his pilots escorted bombers on 200 air combat missions over Europe during World War II.

Davis, whose wife, Agatha, died this year, leaves a sister.

July 7, 2002

General Benjamin O. Davis, Leader of Tuskegee Airmen, Dies at 89

Genreal Benjamin O. Davis Jr., who broke color barriers and shattered racial myths as the commander of the Tuskegee Airmen, the pioneering black fighter pilots of World War II, died on Thursday, July 4, 2002,. He was 89.

He died at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, an Air Force spokesman said.

General Davis, who was a son of the Army’s first black General, Benjamin O. Davis Sr., was the first black cadet to graduate from West Point in the 20th century and one of the first black pilots in the military. His leadership of America’s only all-black air units of World War II helped speed the integration of the Air Force, and in 1954 he became its first black General.

Like his father, General Davis struggled against racism. He was ostracized at West Point and then was barred from commanding white troops and turned away from segregated officers’ clubs in the war years.

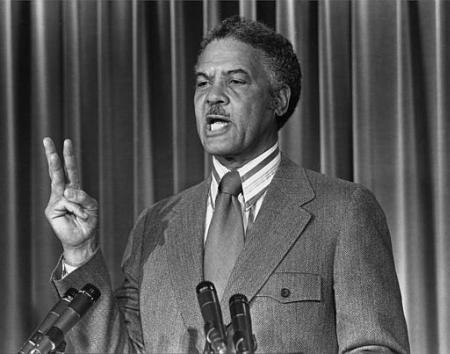

A trim 6 feet 2 inches with a sometimes piercing gaze, a deep voice and an erect military bearing, General Davis carried himself with the knowledge that the stakes were huge: The wartime performance of his men was closely watched by officials who believed that blacks lacked the intelligence and courage to succeed as pilots.

“All the blacks in the segregated forces operated like they had to prove they could fly an airplane when everyone believed they were too stupid,” General Davis said years later.

The airmen commanded by General Davis compiled an outstanding record in combat against the Luftwaffe in the European theater in World War II. They shot down 111 enemy planes and destroyed or damaged 273 on the ground at a cost of more than 70 pilots killed in action or missing. They never lost an American bomber to enemy fighters on their escort missions.

As the leader of dozens of missions in P-47 Thunderbolts and P-51 Mustangs, General Davis was highly decorated, receiving the Silver Star for a strafing run into Austria and the Distinguished Flying Cross for a bomber-escort mission to Munich.

In his autobiography, “Benjamin O. Davis Jr.: American” (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991), General Davis told of the pressures that he and the fliers who came to be known as the Tuskegee Airmen, for the base where they trained, had encountered in the face of racism. “We would go through any ordeal that came our way, be it in garrison existence or combat, to prove our worth,” he said. “Our airmen considered themselves pioneers in every sense of the word.”

Benjamin Oliver Davis Jr. was born on December 18, 1912, in Washington, his mother having returned home while his father was stationed in Wyoming as a Lieutenant with an all-black cavalry unit. At 14, he went up with a barnstorming pilot at Bolling Field in Washington in an open-cockpit plane, wearing goggles and a helmet, and after a few dives and steep turns had “a sudden surge of determination to become an aviator.” Lindbergh’s solo flight across the Atlantic in 1927 inspired him all the more.

After attending the University of Chicago, he entered the United States Military Academy in 1932, having been sponsored by Representative Oscar De Priest of Chicago, the only black member of Congress. His father had been denied an appointment to West Point.

In his four years at West Point, no one would room with Cadet Davis and no one would speak to him outside the line of duty. But he surmounted the bigotry and isolation and graduated 35th in a class of 276, only the fourth black graduate in the military academy’s history.

“Living as a prisoner in solitary confinement for four years had not destroyed my

personality, nor poisoned my attitude toward other people,” he would write in recalling his thoughts upon graduating. “I had even managed to keep a sense of humor about the situation; when my father told me of my many supporters, the many people who were pulling for me, I said, ‘It’s a pity none of them were at West Point.'”

When he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in 1936, the Army had a grand total of two black line officers — Benjamin O. Davis Sr. and Benjamin O. Davis Jr.

At the start of his senior year at West Point, Cadet Davis applied for the Army Air Corps but was rejected because it did not accept blacks. He had hoped that he would at least be assigned to duty with white troops, but his first posting was with the all-black 24th Infantry Regiment at Fort Benning, Georgia. He was not allowed inside the base officers’ club, a snub he would regard as one of the greatest insults of his 37 years of military life.

He later attended the Army’s Infantry School at Fort Benning, but then was assigned to teach military tactics at Tuskegee Institute, a black college in Alabama, something his father had done years before. It was the Army’s way to avoid having a black officer command white soldiers in the days when segregation prevailed and black troops performed menial tasks with little hope of promotion.

For years, his father had been rotated from one noncombat post to another, often teaching assignments at black colleges, to keep him from commanding white troops. Benjamin O. Davis Sr. served 42 years before he was given the star of a Brigadier General.

Early in 1941, responding to pressures for broader black participation as war approached, the Roosevelt administration told the War Department to create a black flying unit.

Captain Davis was assigned to the first training class at Tuskegee Army Air Field, and in March 1942 he won his wings as one of five black officers to complete the flying course. In July — having been promoted to Lieutenant Colonel — he was named commander of the first all-black air unit, the 99th Pursuit Squadron.

The fighter squadron went to North Africa in the spring of 1943 and on June 2, operating out of Tunisia, saw combat for the first time, a dive-bombing mission against the German-held island of Pantelleria. During the summer, the 99th squadron flew missions supporting the invasion of Sicily.

In September, Colonel Davis was called back to the United States to command the 332nd Fighter Group, a larger all-black unit preparing to go overseas. But soon afterward, it seemed that the military was about to scuttle its use of black pilots in combat. The top brass of the Army Air Forces recommended to the Army chief of staff, General George Marshall, that the 99th be removed from tactical operations on the ground that it had performed poorly.

“The Negro type has not the proper reflexes to make a first-class fighter pilot,” one Army Air Forces officer maintained.

Having never been told of any deficiencies, Colonel Davis was incensed. He held a news conference at the Pentagon to defend his men and then stated his case to a War Department committee studying the use of black servicemen.

General Marshall ordered a top-level inquiry, but permitted the 99th squadron to continue fighting. Months later, the inquiry rated the 99th’s performance as comparable to those of other air units in the Mediterranean theater. But questions about the squadron had essentially been put to rest in January 1944, when its pilots downed 12 German fighter planes in two successive days over the Anzio beachhead in Italy.

Colonel Davis and his 332nd Fighter Group arrived in Italy soon after that. Based at

Ramitelli, and called the Red Tails for the distinctive markings on its planes, the

four-squadron unit compiled an outstanding record on missions deep into German territory.

In the summer of 1945, Colonel Davis took over the all-black 477th Bombardment Group, which was stationed at Godman Field, Kentucky.

In July 1948, President Truman signed an executive order providing for integration of the armed forces. Colonel Davis helped draft an Air Force blueprint on integration that went into effect the next year, the wartime performance of his fliers having already created a climate for ending segregation.

General Davis served at the Pentagon and in overseas posts over the next two decades. He gained the three stars of a lieutenant general in May 1965, when he was the chief of staff for American forces in South Korea. He was later commander of the 13th Air Force, based in the Philippines, and assistant commander of the United States Strike Command, with headquarters in Florida.

In 1998 President Bill Clinton awarded him a fourth star, the military’s highest peacetime rank.

General Davis retired from the military in 1970, then became director of public safety in Cleveland, serving in the administration of Carl Stokes, the first black to be mayor of a large American city. Brought in to stem a rising crime rate and ease tensions between blacks and the city’s police, he stayed in the post for only six months, then resigned over what he saw as the Stokes administration’s failure to deal firmly with black extremist groups.

He then joined the United States Department of Transportation, directing antihijacking efforts. In his five years with the department, he supervised the sky marshal program, security measures at airports and programs to curb cargo thefts.

He is survived by a sister, Elnora Davis McLendon, of Washington. His wife, Agatha, died in March.

In June 1987 — more than a half-century after graduating from West Point — General Davis returned there to see the changes that had been made since the days he was a social outcast and to use its archives for his autobiography.

He walked into the visitors center to see an exhibition titled “The Great Train of Tradition” — photographs of outstanding cadets from 1819 to 1950.

The Class of 1936 was represented by photos of just two graduates: General William C. Westmoreland, the commander of American forces in Vietnam and a former superintendent at West Point, and General Davis. Under his picture were the words: “World War Hero, Helped Integrate Air Force.”

CITATION

BENJAMIN O. DAVIS, JR.

General Davis attended Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, and the University of Chicago before being appointed to West Point in 1932. He graduated in 1936 and was commissioned in the Infantry. Benjamin Davis had always wanted to fly, but the Army Air Corps was not open to black Americans in 1936. After a year of service with the 24th Infantry Regiment at Fort Benning, he attended the Infantry School and was then assigned as Professor of Military Science and Tactics at the University of Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

In February of 1941 he was appointed Aide to the Commanding General, 4th Cavalry Brigade at Fort Riley, Kansas. With war imminent, the Roosevelt administration reversed the policy of excluding blacks from flight training. Thus, in April 1941, General Davis was transferred to Tuskegee Army Air Field, where he joined the first class of black aviators.

In March 1942, General (then Captain) Davis received his pilot’s wings, and two months later he transferred to the Army Air Corps. Placed in command of the first black Air Force unit, the 99th Pursuit Squadron at Tuskegee Army Air Field, he moved with the Squadron to North Africa in 1943, and later to Sicily. Under the leadership of then Lieutenant Colonel Davis, the 99th Pursuit Squadron had a distinguished record in aerial combat and in close ground support missions. The unit established itself as a premier fighter squadron in the European Theater, an achievement made possible largely through the efforts of Lieutenant Colonel Davis. General Davis returned to the United States in October 1943, and took command of the 332nd Fighter Group at Selfridge Field, Michigan. Two months later he returned with this organization to Italy.

At the end of World War II, General Davis returned to the United States and took command of the 477th Composite Group at Godman Field, Kentucky. He later assumed command of the Field. In March 1946, he was assigned to Lockbourne Army Air Base in Ohio, where he was Base Commander, and later Commander of the 332nd Fighter Wing.

After attending the Air War College in 1949-50, General Davis was assigned to the Office, Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations, Headquarters, United States Air Force, in Washington, DC. In 1953, he completed the advanced jet fighter gunnery school at Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada.

In November 1953, he became Commander of the 51st Fighter-Interceptor Wing, Far East Air Forces, Korea. In 1954, General Davis was appointed Director of Operations and Training, Far East Air Force Headquarters, Tokyo, Japan. In 1955, he assumed the position of Vice Commander, Thirteenth Air Force, with the additional duty of Commander, Air Task Force 13 (Provisional), Taipei, Formosa.

In 1957, General Davis arrived at Ramstein, Germany, as Chief of Staff, 12th Air Force, United States Air Forces, Europe. Shortly thereafter, he assumed new duties as Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations, Headquarters, United States Air Forces, Europe. Back in the United States in 1961, General Davis became Director of Manpower and Organization, Deputy Chief of Staff for Programs and Requirements, Headquarters, United States Air Force, in Washington, DC.

Promoted to Assistant Deputy Chief of Staff Programs and Requirements in early 1965, he held the position only a few months before being posted to Korea, where he became Chief of Staff for the United Nations Command and US Forces in Korea. In 1967, General Davis assumed command of the Thirteenth Air Force at Clark Air Force Base, in the Philippines.

In August 1968, General Davis returned again to the United States to become Deputy Commander-in-Chief, US Strike Command, at MacDill Air Force Base, Florida. In February 1970,

General Davis retired from the Air Force with the rank of Lieutenant General, completing an illustrious career of 38 years of military service to his country.

Among the many military decorations awarded General Davis were both the Army and Air Force Distinguished Service Medals; the Defense Distinguished Service Medal; the Silver Star, the Legion of Merit with two oak leaf clusters; the Distinguished Flying Cross; the Air Medal with four oak leaf clusters; the Army Commendation Medal with oak leaf cluster; the Air Force Commendation Medal with two oak leaf clusters; and numerous foreign decorations.

In September 1970, General Davis was selected to be Director of Aviation Security in the Department of Transportation, and he returned to Washington, DC. Less than a year later, General Davis was appointed Assistant Secretary of Transportation for Safety and Consumer Affairs. In this new position, General Davis faced an immense and critical challenge in combating a widespread increase in aircraft hijackings and cargo theft. By 1975, when General Davis left the Department of Transportation, he had successfully accomplished his mission, dramatically reducing cargo thefts and almost completely eliminating hijacking of aircraft within the continental United States.

In 1987, the Office of the Air Force History published “Makers of the United States Air Force.” General Davis was one of only 12 outstanding leaders included in that anthology. In describing his contribution to the Air Force, the book stated, “Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. can claim a larger measure of credit for inaugurating this critical reform integration of the Air Force than any other person. For that pioneering accomplishment, America stands in his debt”

Throughout his career, General Davis has never deviated in thought or action from the words he expressed in his autobiography: “I have fought all my life for the integration of blacks into the mainstream of American life.”

General Davis’ life serves as an example to all Americans; his career exemplifies uncommon dedication to the ideal of selfless service and is clearly in keeping with the finest traditions expressed in the motto of the Military Academy: Duty, Honor, Country.

Accordingly, the Association of Graduates of the United States Military Academy is proud to present the 1995 Distinguished Graduate Award to Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., USMA Class of 1936.

Courtesy of the United States Air Force:

GENERAL BENJAMIN O. DAVIS JR.

Retired February 1, 1970

Advanced to General December 9, 1998

Died July 4, 2002

Lieutenant General Benjamin Oliver Davis Jr., was deputy commander in chief, U.S. Strike Command with headquarters at MacDill Air Force Base, Fla. He has additional duty as deputy U.S. commander in chief, Middle-East, Southern Asia and Africa.

General Davis was born in Washington, D.C., in 1912. He graduated from Central High School in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1929, attended Western Reserve University at Cleveland and later the University of Chicago. He entered the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y., in July 1932 and graduated in June 1936 with a commission as a Second Lieutenant of Infantry.

In June 1937 after a year as commander of an infantry company at Fort Benning, Georgia, he entered the Infantry School there and a year later graduated and assumed duties as professor of military science at Tuskegee Institute, Tuskegee, Alabama. In May 1941 he entered Advanced Flying School at nearby Tuskegee Army Air Base and received his pilot wings in March 1942.

General Davis transferred to the Army Air Corps in May 1942. As commander of the 99th Fighter Squadron at Tuskegee Army Air Base, he moved with his unit to North Africa in April 1943 and later to Sicily. He returned to the United States in October 1943, assumed command of the 332d Fighter Group at Selfridge Field, Michigan, and returned with the group to Italy two months later.

He returned to the United States in June 1945 to command the 477th Composite Group at Godman Field, Kentucky, and later assumed command of the Field. In March 1946 he went to Lockbourne Army Air Base, Ohio, as commander of the base and in July 1947 became commander of the 332d Fighter Wing there.

In 1949 General Davis went to the Air War College, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama; and after graduation, he was assigned to the Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations, Headquarters U.S. Air Force, Washington, D.C. He served in various capacities with the headquarters until July 1953, when he went to the advanced jet fighter gunnery school at Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada.

In November 1953 he assumed duties as commander of the 51st Fighter-Interceptor Wing, Far East Air Forces, Korea. He served as director of operations and training at Far East Air Forces Headquarters, Tokyo, from 1954 until 1955, when he assumed the position of vice commander, Thirteenth Air Force, with additional duty as commander, Air Task Force 13 (Provisional), Taipei,

Formosa.

In April 1957 General Davis arrived at Ramstein, Germany, as chief of staff, Twelfth Air Force, U.S. Air Forces in Europe. When the Twelfth Air Force was transferred to Waco, Texas in December 1957, he assumed new duties as deputy chief of staff for operations, Headquarters U.S. Air Forces in Europe, Wiesbaden, Germany.

In July 1961 he returned to the United States and Headquarters U.S. Air Force where he served as the director of manpower and organization, Deputy Chief of Staff for Programs and Requirements; and in February 1965 was assigned as assistant deputy chief of staff, programs and requirements. He remained in that position until his assignment as chief of staff for the United Nations Command and U.S. Forces in Korea in April 1965. He assumed command of the Thirteenth Air Force at Clark Air Base in the Republic of the Philippines in August 1967.

General Davis was assigned as deputy commander in chief, U.S. Strike Command, with headquarters at MacDill Air Force Base, Fla., in August 1968, and also has additional duty as commander in chief, Middle-East, Southern Asia and Africa.

His military decorations include the Air Force Distinguished Service Medal, Army Distinguished Service Medal, Silver Star, Legion of Merit with two oak leaf clusters, Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal with four oak leaf clusters, Air Force Commendation Medal with two oak leaf clusters and the Philippine Legion of Honor. He is a command pilot.

DAVIS, BENJAMIN O., JR., Gen, USAF (Ret.)

Died on July 4, 2002, in Washington, DC. Husband of the late Agatha Scott Davis. He is survived by his sister, Elnora D. McLendon of Washington, DC; many nephews and nieces. Friends may call JOSEPH GAWLER’S SONS, 5130 Wisconsin Ave. at Harrison St., NW, on Tuesday, July 16, from 6 to 8 p.m. Services will be held at the Center Chapel at Bolling Air Force Base on Wednesday, July 17, 10 a.m., followed by interment in Arlington National Cemetery with Full Military Honors. Memorial contributions may be made to Tuskegee Airmen National Scholarship Fund, PO Box 78967, Los Angeles, CA 90016.

It was the summer of 1926, and Ben Davis was 14 when his father paid $5 for a barnstorming pilot at Bolling Air Field in Washington to take his son for a ride.

By the time the plane landed, Benjamin O. Davis Jr. knew he wanted to be a pilot, a decision that would not only alter his life but have a profound impact on racial integration both in the U.S. military and in the country as a whole.

At Bolling Air Force Base yesterday, Davis, who died July 4 at age 89, was remembered as a pioneer and a hero who shattered racial myths as the commander of the famed Tuskegee Airmen in World War II and later as the first

black general in the Air Force.

“It was here at Bolling Field that General Benjamin O. Davis Jr. gave birth to his dream to fly, and oh, what an aviator he became,” Air Force Colonel Harold Ray, a chaplain, said at the memorial service in the packed Bolling chapel. “It’s only fitting that here at Bolling he take his final flight.”

Davis’s coffin, draped with an American flag, was later carried across the river to Arlington National Cemetery for burial with full military honors. Hundreds of mourners followed behind the horse-drawn caisson that carried the coffin in the hot July sun. Modern Air Force F-15 and F-16 fighters and vintage World War II aircraft — P-51 Mustangs like Davis and his men flew in combat over Europe — soared overhead.

It was a great gathering of Tuskegee airmen, about 200 of them mostly in their seventies or eighties, who came from across the country for a final farewell to the man who led them to battle against bigotry and the Nazi Luftwaffe.

“He was my hero,” said Roscoe C. Brown Jr., a Tuskegee airman who earned a doctorate after the war and is now the director for the Center for Urban Education Policy at the City University of New York.

Some mourners were famous, such as entertainer Bill Cosby, and others were not, such as the many young Air Force enlisted men and women who turned out to honor a legend they had only read about. All had the sense, as Cosby

put it, that they were witnessing “the passing of a major story” in African American history.

During the casket procession, the Tuskegee Airmen stood alongside the young Air Force service members, many of them African American. They stiffened to attention as a rifle party fired a 17-gun salute, a bugler played taps, and the flag was presented to Davis’s sister, Elnora Davis McLendon of Washington.

They were saluting the life of a man who possessed both physical and moral courage, speakers at the Bolling service said.

Born in the District, the son of one of that day’s few black Army officers, Davis was raised with high expectations and high standards.

“He felt there was no excuse for poor performance and bad manners,” said his nephew L. Scott Melville.

Pursuing his dream of aviation, Davis won an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. For four years, he was shunned by classmates, who refused to speak to him except on official business.

“He knew the bigots wanted him to fail, and he was determined to succeed,” Alan Gropman, National Defense University historian, said in his eulogy.

He graduated from West Point in 1936, the fourth black man to do so, but was turned down for assignment to the Army Air Corps.

Davis’s opportunity came in 1940, when he was assigned to flight training at Tuskegee Army Air Field in Alabama, where a black squadron was being formed. In 1942, he was put in command of the 99th Pursuit Squadron, the first all-black air unit.

In interviews and eulogies, several airmen spoke yesterday about the powerful impression the tall Davis, resplendent in his khakis, made upon them when they arrived at Tuskegee.

“He let us know this was an opportunity we just could not fail,” said retired Air Force Colonel Charles E. McGee, 82, of Bethesda. “We were all in the crucible.” Davis, realizing any missteps could destroy the squadron’s chance, was seen by his men as a strict and aloof disciplinarian.

The squadron was sent to North Africa and into combat in the spring of 1943 and was criticized by other Army Air Corps officers who recommended it be disbanded. Back in Washington, Davis heatedly defended his men and was

vindicated by a high-level inquiry.

Davis was soon leading a larger all-black unit, the 332nd Fighter Group, into combat escorting bombers. The unit performed superbly, never losing a bomber to enemy fighters.

Davis flew 60 missions himself and was awarded the Silver Star. “He was a very good pilot,” Brown said. “He kept hot-rods like me under control.”

The performance of the Tuskegee Airmen was a critical step leading to the integration of the armed forces ordered by President Harry Truman in 1948. “General Davis was essential to this transformation,” Gropman said. “He did

this by exploding myths.”

Davis exploded myths throughout his career, Gropman said. Retiring in 1970 as a Lieutenant General, Davis was given a fourth star by President Bill Clinton in 1998.

For McGee, Davis’s legacy is simple: “He worked for the day when we were only Americans and race didn’t matter.”

First Black Air Force General Buried

Wed July 17, 2002

The Air Force’s first black General, Benjamin O. Davis Jr., was remembered at his funeral Wednesday as a combat hero who advanced the integration of the armed forces through leadership and the skill of his pilots.

Davis, 89, leader of the all-black Tuskegee Airmen during World War II, was buried at Arlington National Cemetery after a service at the chapel at Bolling Air Force Base. He died on July 4.

“General Davis’ leadership convinced military commanders that segregation was unnecessary and therefore an unconscionable waste,” Dr. Alan Gropman, a faculty member at the National Defense University, said during his eulogy.

Davis made integration work, Gropman said. “The armed forces set the example for American society.”

Dressed in bright red blazers, members of the Tuskegee Airmen were seated throughout the chapel, listening as Davis was eulogized as a man of physical and moral courage and a genuine American hero.

They snapped a final salute at his grave site.

An Air Force band played as the General’s body was transferred from a horse-drawn caisson. A 17-gun salute was fired. Air Force jets and vintage military aircraft, including a pair of P-51 Mustangs of the type flown by the Tuskegee Airmen in Europe, roared overhead

Davis commanded the 99th Fighter Squadron at Tuskegee Army Air Base in Alabama. The unit moved to North Africa in 1943 and later to Sicily.

In October 1943, Davis assumed command of the 332nd Fighter Group, which escorted bombers on 200 missions over Europe, never losing a plane they had been assigned to escort.

Transportation Secretary Norman Y. Mineta recalled that, after his military career, Davis organized the first federal Sky Marshal program to combat airliner hijackings. He also served as assistant secretary of transportation.

“He is a pioneer; he is a hero; he is a role model,” Mineta said. “And his life of duty, honor and integrity will serve as an example for many generations to come.”

Retired Air Force Colonel Charles F. McGee said the Tuskegee Airmen gathered at Arlington with a single purpose: “To render one final salute to our leader.”

A native of Washington, Davis was a son of Benjamin O. Davis Sr., who rose to Brigadier General in the Army.

Davis Jr. left the Air Force as a Lieutenant General with three stars; at the time, he was the senior black officer in the armed forces. President Clinton awarded Davis a fourth star in 1998, advancing him to full General.

His military decorations include the Air Force and Army Distinguished Service medals, the Silver Star, the Legion of Merit and the Distinguished Flying Cross.

By Eugene Harper

American Forces Press Service

WASHINGTON, July 17, 2002 — I remember our meeting nearly 20 years ago as if it were yesterday. The then-retired three-star had insisted that we meet at my office, despite my deference and offer that we meet at a place convenient to him. But my location was fine for him — next door to where he regularly shopped at the commissary at then-Cameron Station, Alexandria, Virginia.

The once-bustling small installation and the ramrod-straight general are both gone now. Both were victims and success stories: Upscale civilian housing has replaced the military office complex, a success story plucked from being a base closure victim. And the general died July 4 at age 89, the success story of a decorated, honored military careerist after being a victim of discrimination when it was the law and order of the land.

The general walked into my office that day, November 10, 1983, and the room took on an instant air of distinction and pride. He greeted me with a steady, firm hand grip. His physique bested his then-70 years by at least half a century. His dress was informal casual: slacks, open-collared shirt, sports coat. His consuming presence wouldn’t allow me to check out his footwear.

We sat down and talked 45 minutes. Well, he did most of the talking — after all, it was all about him. His voice was crystal clear, not overbearing or officious — and again, his presence wouldn’t allow me to misunderstand a single syllable. His words vividly said “WYSIWYG” before the term for “what you see is what you get” became common in the computer age.

Benjamin O. Davis Jr. came from good stock. His dad had been the first African-American general officer in U.S. history: Brigadier General Benjamin O. Davis Sr. So, too, was the son destined for military duty. On the way, he landed at the U.S. Military Academy back in the day when most men of color had to prove themselves worthy to wear the uniform, let alone be officers and West Pointers. For example, he received the silent treatment from his fellow cadets: No one talked to him because he was black.

But the younger Davis set his sights higher, much higher: He really wanted to take off — to fly, that is. “Flying was the thing to do in the ’20s and ’30s,” he recalled. “It combined the features of sports, art, science, adventure and — particularly in those days — danger.

“When I was at West Point, cadets were indoctrinated on the other armed forces’ branches. We spent three weeks at Mitchell Field (Mich.) in 1935, flying in observation and bomber aircraft. That, along with the interest in flying I always had, caused me to apply for pilot training.”

Davis related that his first application made it from West Point to Army headquarters in Washington. “I met all the requirements academically and physically,” he said. “But in those days of the segregated Army, the answer came back from the chief of the Army Air Corps that because there were no blacks in the Army Air Corps and it was not contemplated to have aviation in any of the black units, the application was disapproved.”

He went on to graduate from the academy and was an infantry officer when the Army contacted him in 1941 at Fort Riley, Kansas. “They approached me because they knew I had applied and had been turned down six years earlier,” he said.

The Army had activated the all-black 99th Fighter Squadron in March 1941 and had formed an Air Corps program to train African-American pilots at Tuskegee Institute, a historically black college in rural Alabama. Military historian Alan Gropman said then-military leaders considered this an experiment at best and “an unwarranted political intrusion” at worst.

The Army felt the 99th needed his professional leadership, Davis said. And, besides his father, no other regular Army black officers except chaplains existed. Davis and 12 others began in that first class; only five completed it. Washouts were not unusual in fighter pilot training — a 50 percent to 60 percent washout rate was average.

“The flight training we received was as good as any you would ever find,” Davis said. “The problem was segregation and its effects on the mind. But that was balanced off against the flying mission — the fact that we were flying airplanes.”

The graduated pilots remained at the Tuskegee base, even as more classes arrived for flight and ground-crew training. Davis assumed command of the 99th in August 1942, and plans were made to deploy. His unit was first scheduled to go to Liberia, but in November 1942, Allied troops landed in North Africa. This meant pilots no longer had to stage in Liberia before flying into the Mediterranean area.

“From our viewpoint in Alabama, it looked as though there were problems in where we would be used, when actually all that was probably involved was an overall change in the tactical mission,” Davis said.

The squadron finally arrived overseas in North Africa in April 1943. By that time, the pilots had about 150 hours in tactical training and flying, Davis recalled. The 99th provided close-air support to ground units and then began escorting bombers to targets in Sicily as Allied forces moved toward Italy.

Davis returned to the states in August 1943 to take command of the all-black 332th Fighter Group. He also addressed mounting criticism of the 99th’s performance overseas.

“We had a lot of complaints that we didn’t shoot down many aircraft,” Davis said. His answer was the 99th didn’t come into contact with many enemy airplanes. He said a unit evaluation questioned the pilots’ aggressiveness, stamina and ability to fight under pressure. A report recommended moving the squadron farther away from the front lines and replacing it with a white unit. He said neither action took place.

The 99th flew more support missions until its pilots broke formation and attacked enemy fighters over the Anzio beachhead in Italy in 1944. In less than five minutes, the pilots shot down five German planes, followed by seven more victories over the next two days.

“I think everybody realized the 99th’s performance at Anzio proved that the bad evaluation had been all wrong,” Davis said. “Without these subsequent events, heaven knows what would have happened, especially after the recommendation that blacks not be continued in combat operations.”

The 332nd Fighter Group deployed to the theater and went on to earn a sterling reputation: According to an Air Force biography, Davis’ 332nd Group flew more than 15,000 sorties against the German air force, shot down 111 enemy aircraft and destroyed another 150 on the ground while losing only 66 of its own aircraft to all causes.

The tails of the group’s P-51 Mustang fighters were painted red, and the unit became known across Europe as “the Red Tails” as thousands of sorties gave rise to its reputation as bomber escorts supreme. Flight discipline in some other escort units was loose, and pilots freely broke formation to go hunting. Davis’ standing order to stay with the bombers was clear. The Red Tails’ crowning and unusual achievement: They never lost a bomber under their escort protection.

Davis moved over to the newly formed Department of the Air Force in 1947 and went on to a variety of assignments and positions throughout the world, including combat flying and command in the Korean War. He retired as a lieutenant general in 1970. He served as an assistant secretary of transportation, setting up the nation’s first sky marshal program.

I hadn’t heard much about General Davis since our meeting in 1983. A work colleague’s parents lived in the same building as Davis and his wife, and my co-worker would confirm his parents’ occasional contact with them.

Then I remember the 1995 cable television movie “The Tuskegee Airmen”; actor Andre Braugher played the general. I recall the story about Davis receiving his fourth star in 1998, the first African American general and, at the time, one of only three to be so honored in retirement. I read his obituary a few days ago, which recounted his illustrious career. And I’ve just viewed a closed-circuit broadcast of the general’s funeral service on July 17 at Bolling Air Force Base, Washington, D.C., where dignitaries and colleagues recounted his life with poise and dignity.

Along with these, I can return to that memorable interview, in that office on that day in November. I can replay those 45 significant minutes in my mind, on demand and unambiguously — just as the general presented himself.

Davis gained a reputation for discipline, esprit de corps and excellence starting with his early Tuskegee days as a no-nonsense leader. We can only hope that his spirit of dedication to duty, honor and country continues to soar among us, just like he flew in the cockpit and in life. Heaven knows what would have happened without him.

(Some material came from an article by the author in the February 1984 SOLDIERS magazine.)

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard