NEWS RELEASES from the United States Department of Defense

No. 510-07 IMMEDIATE RELEASE

April 30, 2007

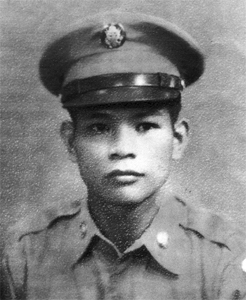

Soldier Missing in Action from the Korean War is Identified

The Department of Defense POW/Missing Personnel Office (DPMO) announced today that the remains of a U.S. serviceman, missing in action from the Korean War, have been identified and will be returned to his family for burial with full military honors.

He is Corporal Pastor Balanon Jr., U.S. Army, of San Francisco, California. He will be buried May 3, 2007, in Arlington National Cemetery near Washington, D.C.

Representatives from the Army met with Balanon’s next-of-kin to explain the recovery and identification process and to coordinate interment with military honors on behalf of the secretary of the Army.

In late October 1950, Balanon was assigned to L Company, 3rd Battalion, 8th Calvary Regiment, then engaging enemy forces south of Unsan, North Korea, near a bend in the Kuryong River known as the Camel’s Head.Chinese communist forces attacked the 8th Regiment’s positions on November 1, 1950, forcing a withdrawal to the south where they were surrounded by the enemy.The remaining survivors in the 3rd Battalion attempted to escape a few days later, but Balanon was declared missing in action on November 2, 1950, in the vicinity of Unsan County.

In 2001, a joint U.S.-North Korean team, led by the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (JPAC), excavated a burial site in Kujang County, south of Unsan County.A North Korean citizen living near the site told the team that the remains were relocated to Kujang after they were discovered elsewhere during a construction project.The battle area was about one kilometer north of the secondary burial site.

Among other forensic identification tools and circumstantial evidence, scientists from the JPAC and the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory also used mitochondrial DNA and dental comparisons in Balanon’s identification.

For additional information on the Defense Department’s mission to account for missing Americans, visit the DPMO Web site at http://www.dtic.mil/dpmo or call (703) 699-1169.

Pastor Balanon, Jr.

- San Francisco, California

- Born May 4, 1928

- Corporal, U.S. Army

- Service Number 10338172

- Missing in Action – Presumed Dead

- Died November 2, 1950 in Korea

Corporal Balanon was a member of Company L, 3rd Battalion, 8th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division. He was listed as Missing in Action while fighting the enemy near Unsan, North Korea on November 2, 1950. He was presumed dead on December 31, 1953.

His name is inscribed on the Courts of the Missing at the Honolulu Memorial.

Corporal Balanon was awarded the Purple Heart, the Combat Infantryman’s Badge, the Korean Service Medal, the United Nations Service Medal, the National Defense Service Medal, the Korean Presidential Unit Citation and the Republic of Korea War Service Medal.

1 May 2007:

For more than 56 years, the family of Corporal Pastor Balanon Jr. never gave up hope that he was alive. He was a professional soldier who had enlisted in the Army in San Francisco, a rifleman in a unit called the lost battalion in a war that has been nearly forgotten.

He was 22 years old when he was a caught in a disastrous battle near the village of Unsan, North Korea. His battalion, outnumbered and outgunned, was overrun by Chinese Communist forces, who came out of the dusk on November 1, 1950. Balanon was never seen again. Missing in action, they said.

“We always hoped that he would come back alive,” said his younger brother, Esteban Balanon, who lives in Belmont on the San Francisco Peninsula. “We never gave up hope.”

“It was very hard, especially for my mother and father,” said Estrella Africa, of Santa Clara, the missing man’s sister. “They never knew what happened to their son.” Both parents died in the 1980s.

Wednesday, Pastor Balanon Jr. will return at last, this time to the hallowed ground of Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

His remains, discovered deep in a well in North Korea in 2001, were identified in October by U.S. authorities using mitrochrondrial DNA matches, dental charts and other forensic evidence.

The funeral at Arlington is the end of what Larry Greer of the Defense POW/Missing Personnel Office calls “a nearly 60-year-long detective case.”

Balanon’s story began when he was born in the Philippines in 1928, when the islands were under the American flag. He will be buried one day before what would have been his 79th birthday.

Balanon was from a military family — his father was a soldier, and so were two of his brothers. His sister was an officer in the Air Force.

Was he patriotic? “Absolutely,” said Esteban Balanon. “He always wanted to join the service,” said his sister.

Esteban said his father, Pastor Balanon Sr., had served with the U.S. Army in the Philippines before World War II, and when the Japanese occupied the islands, the family patriarch had been active in the anti-Japanese guerrillas.

Once, said Esteban, his father and brother were arrested by Japanese police. The boy was hung by his hands and the father was buried alive up to his neck. If the Japanese were seeking information, they didn’t get it.

After the war, Pastor Balanon Sr. stayed in the Army and served until 1954.

Pastor Balanon Jr., moved to San Francisco, lived with his uncle in Hayes Valley and joined the regular Army.

In October of 1950, he was assigned to C Company, Third Battalion, Eighth Cavalry Regiment, then serving in Korea. The Army had just captured Pyongyang, the capital of North Korea, and was pursing the remnants of the North Korean army.

It appeared the United States and its allies, operating under the U.N. flag, had won the war. But there was disaster ahead.

The Communist Chinese regime had warned repeatedly that it might intervene. And there was a wide gap between the territory held by the U.S. and South Korean armies and the U.S. Marines.

The troopers of the Eighth Cavalry, an old-line U.S. regiment, now serving as infantry, had fought its way to the vicinity of Unsan, a village only 50 miles from the Chinese border.

Just at dusk Nov. 1, they ran into two divisions of Chinese troops. The Eighth Cavalry had three battalions, each about 800 men; according to the Korean War Almanac, each Chinese division had 10,000 men.

Many U.S. troops fought until they ran out of ammunition. The Third Battalion, where Balanon was a rifleman, was overrun. Six hundred of its 800 men were killed, captured or missing. They called the Third Battalion the lost battalion.

It was a bitter defeat.

Balanon was one of the men who did not return.

But his family never gave up. They had not given up in the Philippines in World War II, and they would not give up now. They kept his picture in a place of honor. “Some said there were still Americans alive in North Korea after the war,” said Esteban Balanon.

They thought, perhaps, that Balanon had been captured and become a laborer, or had been ill, or…

“You never know what happened,” said Esteban.

Finally, in 2001, the North Koreans allowed a U.S. team to go to their country and look for remains of missing service members. Near the town of Unsan, some Koreans said they had discovered remains — bones — near a construction site.

Esteban Balanon said he was told that someone, he does not know who, threw the bones down a well. The Americans were told of them, and the remains were disinterred and taken to Hawaii for identification.

It took a long time — more than five years — to identify them. When it became clear that one of the missing men might be Pastor Balanon, his brother and sister were located and DNA samples were taken. It was a match.

Balanon, a Filipino boy who always wanted to be a solider, is one of the last Americans to return from the Korean War. But there are still thousands of Americans missing from wars in Europe and Asia, lying where they fell. In a military cemetery in Honolulu, many more unidentified U.S. service members are buried.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard