U.S. Department of Defense

Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Public Affairs)

News Release

IMMEDIATE RELEASE No. 529-08

June 24, 2008

DoD Identifies Army Casualties

The Department of Defense announced today the death of four soldiers who were supporting Operation Enduring Freedom. They died June 21, 2008, in Kandahar City, Afghanistan, of wounds suffered when their vehicle encountered an improvised explosive device and small arms fire.

Killed were:

Lieutenant Colonel James J. Walton, 41, of Rockville, Maryland, who was assigned to a Military Transition Team, 1st Brigade, 1st Infantry Division, Fort Riley, Kansas.

Specialist Anthony L. Mangano, 36, of Greenlawn, New York, who was assigned to 2nd Squadron, 101st Cavalry (Reconnaissance, Surveillance and Target Acquisition), New York Army National Guard, Geneva, New York.

Sergeant Nelson D. Rodriguez Ramirez, 22, of Revere, Massachusetts who was assigned to 2nd Squadron, 101st Cavalry (Reconnaissance, Surveillance and Target Acquisition), New York Army National Guard, Geneva, New York.

Sergeant Andrew Seabrooks, 36, of Queens, New York, who was assigned to 2nd Squadron, 101st Cavalry (Reconnaissance, Surveillance and Target Acquisition), New York Army National Guard, Geneva, New York.

June 25, 2008:

On his days off, Lieutenant Colonel James J. Walton liked to parachute out of airplanes and bike long distances – once embarking on a weeklong trek from Richmond, Virginia, to Lexington, Kentucky.

The career soldier, who relatives said never complained about two deployments and whose fourth wedding anniversary would have been tomorrow, was killed Saturday in Kandahar, Afghanistan. He was 41.

As a member of an Army Military Transition Team, Colonel Walton trained Afghan soldiers. It was a job he enjoyed, although he often reported to his family about its front-line danger, his father-in-law, Joseph Moschler, said yesterday.

He was killed when his convoy encountered a roadside bomb and small-arms fire, according to the Defense Department.

“He was there to train the Afghan military, and he looked forward to it, he believed in it and he cared about it,” said Mr. Moschler, of Midlothian, Virginia. “He was the most dedicated man to his job I have ever known.”

Colonel Walton was a Rockville native and West Point graduate.

Several years ago, he was deployed to Iraq. Upon his return, he joined the Military Transition Team, 1st Brigade, 1st Infantry Division, based at Fort Riley, Kansas. He was deployed to Afghanistan in December.

“As a youngster, he set his sights early on West Point,” said his sister, Kyle Cottrell, who is a retired Lieutenant Colonel in the Marines. “There was a feeling in my family: To whom much is given, much is expected. The manner in which we chose to do that was in the military. It was an avenue to which we could give something back to a country that gave so much to us.”

The family learned of Colonel Walton’s death during a reunion at a beach in Virginia, his sister said.

“It has been a blessing that we could all be together and share laughter and tears,” she said.

They have shared stories of “Jimmy,” the second-youngest of five children, a standout on the diving team at West Point, an optimistic “born leader” who was always trying something adventurous, from rock climbing and rappelling to flying.

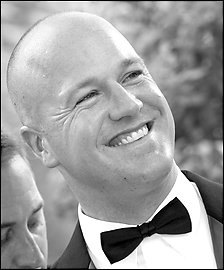

In photos, he stood out. He was the tall and sturdy one with a bald head and – always – a huge grin, she said.

Colonel Walton had a pilot’s license and belonged to a club where he could rent small planes from time to time, taking his father-in-law on rides.

He was an enthusiastic paratrooper, logging more than 5,000 jumps, Mr. Moschler said. Upon retirement, he hoped to join the Golden Knights, an Army parachuting team based at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

His wife, Sarah Moschler Walton, shared her husband’s love of athletics. The two met at an Arlington, Virginia, fitness club five years ago, dating a year before they married. The couple settled in Arlington, and Colonel Walton worked at the Pentagon.

Mr. Moschler said he approved of him instantly.

“I thought he was the most wonderful young man I have ever known in my life,” he said. “I loved him just like my own.”

Colonel Walton was deployed twice during his marriage, and he and his wife made the most of their time together, often going hiking and running, Mr. Moschler said. The two loved animals, volunteered at animal-rescue facilities and had a pet cat and a dog, a mutt named Hannibal that they had rescued from abuse.

They also planned to adopt a child, Mr. Moschler said.

“She was with us when she learned of this Saturday night, and of course it hit her like a bolt of lightning,” Mr. Moschler said of his daughter. “She was hysterical, even though she was half-prepared for it.

“Sarah knew that Jim was a professional soldier, and she never complained about it,” her father said. “Of course she wanted him home, but she understood his first obligation was his country, and she never complained.”

And Colonel Walton believed in his work.

“He told me one of the last times I talked to him, ‘I think the Lord put me on this earth for a special purpose – to help people who can’t help themselves. That’s why I’m here, and that’s what I intend to do,'” Mr. Moschler remembered him saying. “He was the most unassuming, humble man I ever knew. He never wanted to draw attention to himself.”

Soldier Was Dedicated to Service

By James Hohmann

Courtesy of the Washington Post

Thursday, June 26, 2008

Lieutenant Colonel James J. Walton and his wife, Sarah, would have celebrated their fourth wedding anniversary today.

But Walton, 41, who grew up in Rockville, Maryland, and had been living in Arlington County, Virginia, died Saturday in the Kandahar province of Afghanistan after his vehicle struck a roadside bomb and his convoy came under fire, the Army said.

Word came as Walton’s parents, four siblings and eight nieces and nephews were assembling at a Delaware beach for an annual family retreat.

“What everyone remembers about Jim is, he was larger than life,” said his sister Diane Jewell, 34. “He’s exactly what you’d think of when you think of a hero.”

He left goodbye letters for his parents, wife, in-laws and siblings. Yesterday, the family was planning to mail notes he wrote for some of his buddies.

The Army said Walton’s unit, part of the 1st Infantry Division, had been training and mentoring Afghan soldiers.

People who knew him said he believed passionately in the military’s mission and the work he was doing overseas. In May, he wrote two e-mails to a New York talk radio station, one of which said that “the enemy” was “acting up” with the end of the poppy-harvesting season.

Walton knew in fourth grade that he wanted a career as a soldier, Jewell said. At St. John’s College High School in the District, Walton was elected the equivalent of student body president, she said. In May 1989, after graduating from West Point, he entered the Army. Since getting married, he had served a tour in Iraq and was assigned to the Pentagon.

In the early 1980s, Walton was an altar boy for Monsignor John F. Myslinski, now the pastor of St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Rockville. Myslinski said the family reminded him — and not just in name — of the fictional characters on “The Waltons,” the 1970s TV show.

“They were blond, wholesome . . . and close-knit,” he said.

The two men stayed in touch. The pastor blessed Walton’s wedding ring and gave him a finger rosary before he left. In one of their last conversations, Walton told Myslinski he wanted to be active in the parish when he returned. Instead, Myslinski will preside over Walton’s funeral at Arlington National Cemetery.

There wasn’t a sport Walton couldn’t excel at, his family said, including springboard diving, kayaking and rock climbing. For recreation, he went for long bike rides and parachuted with friends. In 2005, he was on a team of 85 skydivers that claimed a world record for holding together an estimated 276-foot-tall formation above Florida.

“To say you could always take him at his word was an understatement,” said Frank Matrone, the best man at his wedding and a participant in that jump. “I never saw him make a bad decision. He was an all-around great guy.”

Walton and his wife nurtured abused animals, including an adopted dog, Hannibal.

“Jimmy was a champion for the underdog,” said sister Kyle Cottrell, a retired Marine Lieutenant Colonel. “He had a soft spot in his heart for people who couldn’t help themselves.”

Kenneth Holmberg, who lives two doors down from Walton’s townhouse, remembered when a neighbor locked herself out. Walton grabbed a long ladder, climbed in through her bathroom window and came out the front door with the woman’s keys in hand, he said.

“We all prayed for him when he was gone,” Holmberg said. “Sometimes prayers aren’t enough.”

NOTE: Services for Colonel Walton were held at the Memorial Chapel at Fort Myer, Virginia, at 8:45 AM on 10 July 2008, followed by burial with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery.

The Knock on the Door

By George F. Will

Sunday, July 6, 2008

Courtesy of The Washington Post

“The curtains pull away. They come to the door. And they know. They always know.”

— Maj. Steve Beck, U.S. Marine Corps

Sometimes Beck would linger in his vehicle in front of an American home, like that of the parents of Lance Cpl. Kyle Burns in Laramie, Wyo. Beck knew that, as Jim Sheeler writes, every second he waited “was one more tick of his wristwatch that, for the family inside the house, everything remained the same.”

Beck — now Lieutenant Colonel Beck — was a CACO, a casualty assistance calls officer whose duty was to inform a spouse or parents that their Marine had been killed. He is the scarlet thread — like the stripes on Marines’ dress-blue trousers, symbolizing shed blood — that connects the heart-rending stories in Sheeler’s “Final Salute: A Story of Unfinished Lives.” The book, which proves that the phrase “literary journalism” is not an oxymoron, expands the meticulous and marvelously modulated reporting that he did for the Rocky Mountain News and for which he received a Pulitzer Prize. His subject is how America honors fallen warriors.

More precisely, it is about how the military honors them. The nation, as Marine Sergeant Damon Cecil says, “has changed the channel.” Still, Sheeler sees civilians getting glimpses of those who have sacrificed everything. The glimpses come as the fallen are escorted home. When an airline passenger, noting an escort’s uniform, asked if the sergeant was going to or coming from the war, he repeated words the military had told him to say: “I’m escorting a fallen Marine home to his family from the situation in Iraq.”

The situation. Sheeler:

“When the plane landed in Nevada, the sergeant was allowed to disembark alone. Outside, a procession walked toward the cargo hold. The airline passengers pressed their faces against the windows.

“From their seats in the plane they saw a hearse and a Marine extending a white-gloved hand into a limousine. In the plane’s cargo hold, Marines readied the flag-draped casket and placed it on the luggage conveyor belt.

“Inside the plane, the passengers couldn’t hear the screams.”

The knock on the survivors’ door is, Beck says, “not a period at the end of their lives. It’s a semicolon.” Deployed military personnel often leave behind, or write in the war zone, “just in case” letters. Army Private First Class Jesse Givens of Fountain, Colorado: “My angel, my wife, my love, my friend. If you’re reading this, I won’t be coming home. . . . Please find it in your heart to forgive me for leaving you alone.” To his son Dakota: “I will always be there in our park when you dream so we can still play together. . . . I’ll be in the sun, shadows, dreams, and joys of your life.” To his unborn son: “You were conceived of love and I came to this terrible place for love.”

The manual for CACOs says, “It is helpful if the [next of kin] is seated prior to delivering the news. . . . Speak naturally and at a normal pace.” Sometimes, however, things do not go by the book.

Doyla Lundstrom, a Lakota Sioux, was away from her house when she learned that men in uniform had been to her door. She called the father of her two sons — each serving in Iraq; one as a Marine, one as a soldier — and screamed into her cellphone, ” Which one was it?” It was the Marine.

Sheeler says that troops in war zones often have e-mail and satellite telephones, so when someone is killed, communication from the area is stopped lest rumors reach loved ones before notification officers do. “As soon as we receive the call,” Beck says, “we are racing the electron.”

When the Army CACOs came to the Arlington door of Sarah Walton, my assistant, she was not there. She rarely forgot the rule that a spouse of a soldier in a combat zone is supposed to inform the Army when he or she will be away from home. This time Sarah forgot, so it took the Army awhile to locate her at her parents’ home in Richmond.

Her husband, Lieutenant Colonel Jim Walton, West Point Class of 1989, was killed in Afghanistan on June 21, 2008. This week he will be back in Arlington, among the remains of the more than 300,000 men and women who rest in the more than 600 acres where it is always Memorial Day. This is written in homage to him, and to Sarah, full sharer of his sacrifices.

WALTON, JAMES J

- LTC US ARMY

- DATE OF BIRTH: 03/31/1967

- DATE OF DEATH: 06/21/2008

- BURIED AT: SECTION 60 SITE 8260

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard